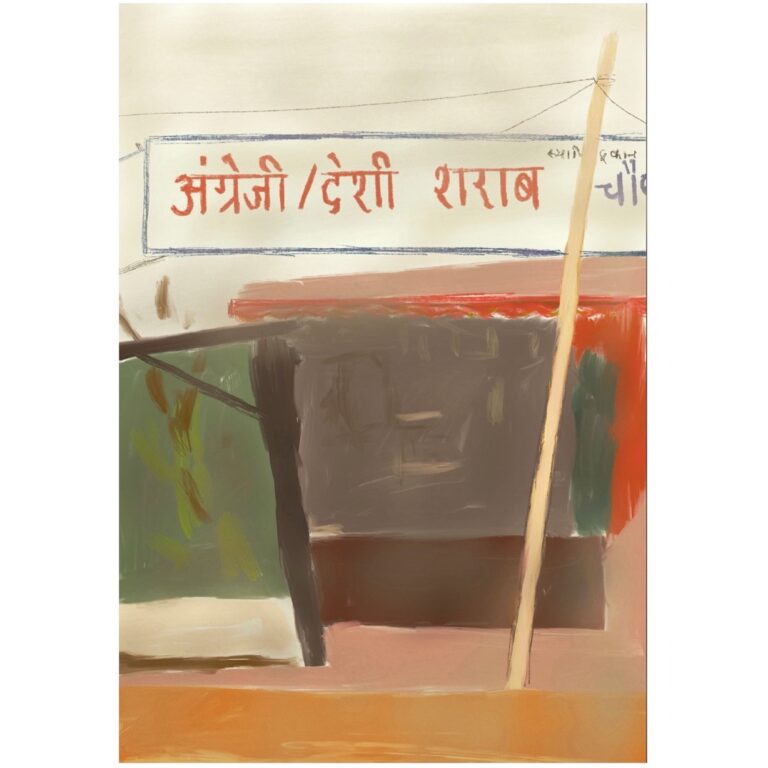

Particulate matter, Delhi liquor shop

The last time I was in Delhi it was hot. So hot that there were reports of overheated birds falling from the sky. But now it was winter. It was foggy outside, the air smelling acrid. I had brought masks; they were no use. Very quickly I developed a sore throat and then a cough. When I complained about this to my publisher, he showed me a news item on his phone. ‘Weather trends show capital no longer gets benign fog.’ Delhi’s air was described as carrying ‘a large share of chlorides, sulphates and nitrates, and ions of calcium and ammonium’. I asked a friend of mine about the phrase ‘particulate matter’ – I had heard the term used to describe what gave the atmosphere its dark colour. My friend said it would be a good title for a Delhi painting.

All over Delhi the billboards showed a picture of Narendra Modi and the words: Mother of Democracy to Host G20. The event is planned for September 2023. I had slept a few hours but was still jet-lagged when I met a friend for dinner on my first night back in Delhi. I asked for news. The news came from New York, the city I had left a day earlier. My friend said that at the UN, the Indian Foreign Minister had reminded the world that Pakistan had hosted Osama Bin Laden. In response, the Pakistan Foreign Minister, Bilawal Bhutto, had said at a press conference that ‘Osama Bin Laden is dead, but the butcher of Gujarat lives and he is the Prime Minister of India.’ A day or two later, a BJP leader announced that he would award two crore rupees (about a quarter million dollars) to anyone who would behead Bhutto. Which is all to say, there was quite a bit of toxicity in the air.

The author’s father with his grandson

When I traveled to India last, I was unable to get a visa for my son, who was then twelve. This was because my wife was born in Pakistan. Because of this, security clearance had to be provided by the Indian Home Ministry. I had to cancel my son’s ticket. This time I applied well in advance, and I also appealed to a senior official in the foreign service who had been in high school with me. This time my luck held.

My father, who is nearly ninety, was interested in showing my son our ancestral homestead. Jadopur, our village, is several hours’ drive from Patna. When we entered the village, the placidity of the place reminded me how much I missed it. When I visited the village as a schoolboy, I had always wanted to draw or photograph what I saw. My son got out of the car. Corn had been planted in one of our fields; the young plants were only ankle high. Several months ago, my father was told that someone else had ploughed the field. Another family in the village claimed that they had papers from the beginning of the last century showing ownership. This news had come as a blow to my father. My sister said that it left him disoriented. But then my father found the documents of sale that showed that the land had indeed been bought, back when he was a boy, from the family that was now claiming the land.

I took my son on a walk to the village school that my father had built in my grandmother’s memory. My father had been the first person in the entire district to get selected for the Indian civil services; education had been his ticket out of the village. Most of his other relatives worked the land; a cousin became a doctor but others, if they left Jadopur, managed only to find low-paying jobs. When I was a child my grandfather had been the village headman, but by the time I was in my teens power had shifted. My grandfather lost the panchayat election to a man from a lower caste. The family has little land remaining, but my father, perhaps because he feels he must give back what he owes to the land, has cultivated a philanthropic side.

At the school, boys were playing cricket. A middle-aged woman approached me. In a show of outdated modesty she had covered the lower part of her face, but I could see that she was smiling. She said that it was good I had come back, and then, pointing to a field close by, she said that a distant cousin of mine was now claiming that the land was his. I was taken aback. My relationship to the village was already tenuous, uncomfortably distant. Now it felt under threat. For decades, this land had been in the possession of my family. I didn’t know what to say. I wasn’t really back. I wasn’t in a position to do anything. I was just visiting.

The thought came to me again. When my father was gone, a large part of my past would disappear, like one of those videos you see of landslides, an entire cliff with a winding road and cars disappearing into the swirling river. It wasn’t land or property that I was thinking about; I was thinking about my parents, my mother who had come to this village as a young bride, and my father, who had brought me today to the place where he had been born. It was the people who had made my past who would soon be gone.

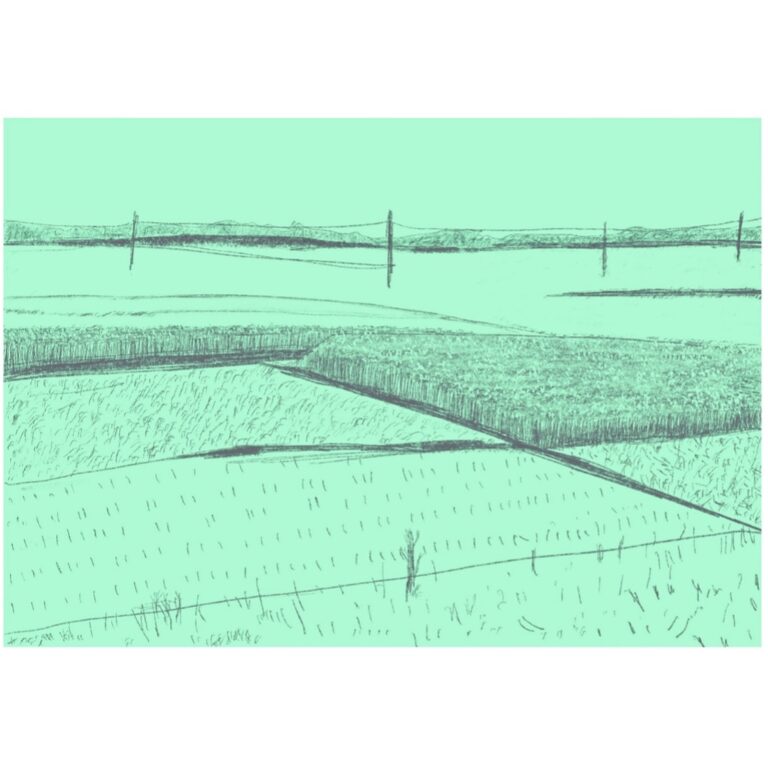

The next day found me in quiet retreat, making a drawing of two adjacent mustard fields I had seen in the village. Is art a retreat from life and its contradictions? The answer would be yes. At least for me, that day. My eye had been attracted by the two intersecting lines of dense green topped by the bright yellow of the mustard, and now I felt compelled to render it all in a somber monochrome.

I remembered both sides of that dirt road from my childhood, and the endless fields that stretched beyond. It was all very peaceful. Difficult to imagine, while looking at the small parcels of land with their neat rows of crops, all the battles over property waged within families and communities. As generations change, the plots are divided among siblings, and grow smaller. There is less and less left to share. People leave for the cities. New buyers take over. This, at least, is what has happened in my village. My grandfather’s land was divided between my father and his two brothers, but none of them live in the village. One of my uncles sold nearly all his land and moved to Bengaluru. I cannot imagine my own family’s link to this rural place lasting beyond me. What I would like is for my father to sell his land during his lifetime, so that the new owners of the land will be from the village. Poorer families who couldn’t simply up and move away. But why was it so hard to tell him this? To bring up the question of land, of inheritance?

Perhaps my father, too, in a far more real way than me, experienced the loss of his past. And he wasn’t going to let it all disappear. He told me how he was a boy of eight or ten when he first saw an electric bulb. The world, and even his village, had changed so much during his long lifetime. He wasn’t going to let me talk him out of the bit of land that had been the one stable corner of his life since his childhood.

A Bihari man working as a driver in Delhi told me a strange story. His name was Deepak. When his mother complained of chronic stomach pains, Deepak brought her from the village for treatment in a hospital in Delhi. The doctors told him that his mother would require surgery; there was a problem in her uterus. After the operation, which incurred a considerable expense, the lady returned to the village. Her health problems, the pain in her stomach, continued. Deepak brought his mother back to Delhi. This time he took her to another doctor who decided to do tests and run some scans. This doctor found that during the previous surgery the mother’s uterus hadn’t been touched at all. Instead, she was now missing a kidney. Deepak and his father went to the first hospital to complain, but were shooed away. Deepak’s parents then returned to the village, and two years later his mother died.

We were driving through Gurugram at that time, passing the high-rise offices that house the likes of Google, Deloitte, Oracle, Microsoft. I didn’t know whether Deepak was talking of this shiny new India when he told me that the poor were scared of cities like Delhi. They will die if they come here. I wanted to tell Deepak that people like him kept the city running, but it would have sounded hollow, and I remained silent.

On the way back from the village, we stopped for a night at my uncle’s home in a shabby small town called Bettiah. A different question about art occurred to me. A few days earlier I had been talking over lunch in Delhi to the young documentary film-maker Shaunak Sen, whose All That Breathes was nominated for an Academy Award in 2022. The film is ostensibly about two Muslim brothers running a bird hospital in old Delhi, feeding pieces of meat to kites, repairing their wings, helping them heal. But the film’s subtlety – and its cunning – lies in the fact that it is really about exciting compassion for all living things, including, in the context of present-day India, our Muslim neighbors. When I asked him to explain his aesthetic, Sen told me that in his documentary he hadn’t been interested in being a fly on the wall. Or in presenting ecstatic truths in the manner of Werner Herzog. Not even forensic truths, where the film-maker investigates the traces that objects leave in life. Instead, Sen said, he wanted to be like an earthworm wriggling under the surface visible to all. He made a statement that stayed with me: ‘Films that reveal their political cards too easily – too early – are actually apolitical.’

I thought about Sen in my uncle’s house. Unlike my father, my uncle didn’t succeed in his studies, and was unable to find a job. For a while he turned himself into a businessman, but in recent decades he has had to cling to the lower rungs of middle-class life. He’s retained his share of the land, collecting his portion of the produce from the farmer who now cultivates it. He lives in a small, crumbling bungalow for which, because of some legal wrangle with the government, he no longer needs to pay rent. What was it about the dilapidated structure that I found so haunting? Remembering Sen’s words, I didn’t want to look at the obvious – the fact of my uncle’s straitened circumstances. I was lying on the hard bed next to my son, observing my surroundings. It wasn’t the damp cracked walls I was interested in noticing, nor the plastic used as a cover on the table, or on the wall to protect from the damp the few clothes hung there from a nail driven into the cement; not the tiny clock hung too high but, instead, the little tin device on the table, which was smoldering mosquito repellant paper. It was that device, on this night, which brought me closest to the cramped spaces and the very air of my childhood. We never had an air-conditioner in the house, or screens on windows to keep out bugs. If you kept the windows open for air, it was necessary to keep the mosquito coil burning next to the bed. In the winter, even with the windows shut against the cold, the mosquito repellant was there, keeping away the mosquitoes, and there was always that same taste of acrid smoke from the coil settling on the base of one’s throat.

The old man in the TV ad isn’t able to recognize his own granddaughter. Next to him is a photograph of the little girl that the granddaughter used to be. In the photograph, the man can be seen caressing the little girl’s cheeks. The granddaughter, now grown up, knows exactly what to do. She applies Pond’s moisturizing cream to her cheeks. When she places the old man’s hands on her cheeks, it is clear that his memory returns, a tear forms in his eye and he calls out the girl’s name.

I watched all this on the TV in my hotel in Jaipur, and felt oddly hailed by the ad – a perfect example of what Marxist philosophers call ‘interpellation of ideology’ – because, however tacky, I felt seen. On this trip, I wanted to be assured that my father was in sound physical and mental health, and, in a different, more remote, drama of recognition, I wanted my old homeland to touch my face and say my name.

Out of curiosity, I looked up the average life expectancy of Indians. In 1963, the year of my birth, our average life expectancy was 42.94 years. Now, it had risen to 70.42. By 2050, a full 19 per cent of the population in India is expected to be over 60 years of age. Another website quoted a Lancet study, forecasting that dementia cases in India were likely to double by the year 2050. What struck me about the figures cited in that study was the jump from 2019 – 3,843,1881 – to a projected total in 2050 – 11,422,692.

India, as we know it, is changing. What will it become? At one end, a land with older citizens, unmoored from their past. And a vast, burgeoning army of the young that, suffering under a system that cannot provide education or employment, are deprived of any real sense of history. For them, can there be any real future?

When my son and I ventured out to the city’s many forts and palaces, it was difficult not to think of summer even in the midst of winter. The Thar desert is several hours’ drive away to the west, but the arid landscape around the city, the scrubland dotted with camel-drawn carts, the deep ravines and even the sandstone buildings all evoked in me a feeling of shimmering heat. And yet, and yet. The guides at the forts and palaces took pains to point out how the structures we were looking at – all examples of what they called ‘Indo-Islamic architecture’, a mix of Hindu and Islamic motifs – allowed the royal inhabitants to enjoy a relative coolness during the hot months. They would point to the elaborate jalis, the perforated stonework screens that permitted cooling breezes to circulate. A palace with 953 windows, big and small. Or limestone surfaces that held the heat during winter and kept cool during summer. Even the terracotta pink of the buildings and shops was meant to blunt the relentless sun. It was difficult not to believe that our ancestors possessed an instinct for ecological soundness. On the other hand, this view of the past seemed little more than a species of nostalgia. Because while the local guides grew eloquent when they described the intricate architecture of the stepwells, the truth was that now they had all run dry.

Outside the Ajmer Sharif Dargah

The forts in particular excited awe in my heart: how were these massive, elegant structures built on hills? Or palaces in the middle of lakes? I was told this took decades. There was a rush of excited tourists everywhere. My taxi driver said that he would have no work when the summer came. It would be too hot and the flow of visitors would dry to a trickle. Nevertheless, I didn’t find the crowds that were everywhere in the city, and even outside of it, enjoyable in the least. In the press of bodies at the shrine in Ajmer Sharif there was only desperation. It was the same at Pushkar, about three hours away. The first was filled primarily with Muslim devotees and the second mostly Hindu, but in both places we were set upon by religious intermediaries who acted as guides, and led us to accountants who accepted donations to the trusts governing those places. If you turned away from the window where a man sat waiting to write a receipt, you saw the worshippers praying fervently. And why wouldn’t they? For a job, for a loved one’s health, for a measure of peace.

On New Year’s Eve, about an hour before midnight, I spoke to a man who was in the desert. His name is Shyam Sunder Jyani and he teaches at a government college in Bikaner. Since the year 2006, he has worked on turning the desert green, convincing families in more than 18,000 villages to plant trees. His message is a simple one: your family is incomplete if you do not have a ‘green member’. Jyani encourages everyone to plant fruit trees. He says that more than 3.8 million trees have been planted in the desert districts because of his campaign. The United Nations has given him an award.

My father had told me during our trip to Jadopur that he had planted mango trees in the village. He said he had been inspired by something my grandmother had said before her death. Does a mango tree stop producing mangoes, she had asked, just because it will not get to eat its fruit? This had sounded to my ears like a well-worn cliché, but now, listening to a stranger in Rajasthan, I felt that what I was being told was perhaps true.

The new year was about to dawn. I was desperate myself, desperate for any good news. I wanted to be full of hope, and took down every word Jyani was saying. He said that if I came in the summer he would feed me jujube berries that he had grown without using a single drop of water.

I don’t think of myself as someone who is looking for the miraculous, but there was so much bad news all around that I wanted to believe him. It is so easy for those in power in India to throw someone behind bars, or to destroy their homes with a bulldozer, that it is difficult at times to remember that small people too have will, and agency.

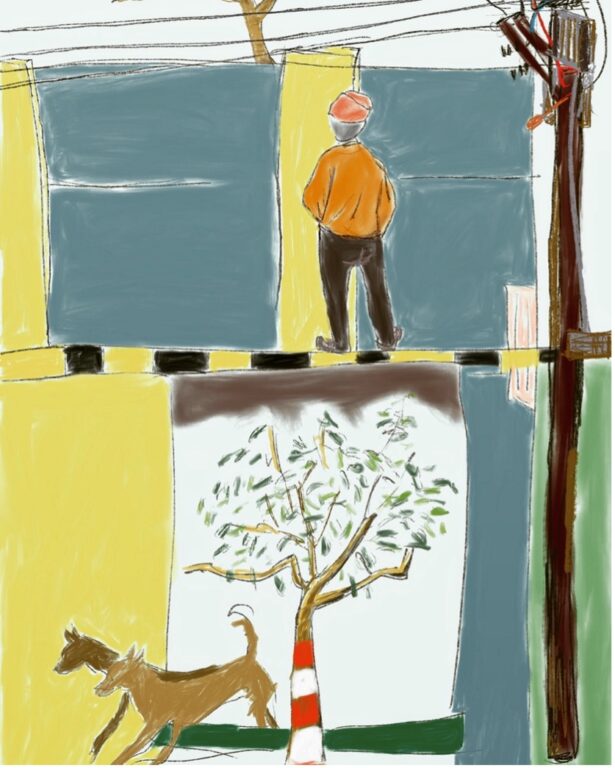

Pissing Man, Patna

A week later. On my last evening in Delhi, I did a reading at a bookstore from my book on Patna. My interlocutor at the event was a poet and a diplomat – he was in charge of the cultural events for the upcoming G20 summit. He said that works like my book on Patna, with their description of men urinating on the wall outside my father’s house, are favored in the West and win prizes like the Booker. (He was referring to a piece I had written for Granta in which I had remarked that if Frederico Lorca had been from Patna, his poem ‘Landscape of a Pissing Multitude’ would have been a long epic.) I was stung by the remark, not least because I haven’t won such prizes. It was equally important for me to point out to our audience that while my diplomat-friend was taking exception to my mention of the line of men peeing on the street outside my father’s house, the truth was far worse. Just that day we had all learned that an Indian man on a New York-Delhi Air India flight had urinated on a co-passenger, an old woman who had been sleeping on her seat.

The audience members were laughing at my remarks; someone even clapped. I felt annoyed. It is a familiar ploy adopted these days by the ruling party in India: any criticism of the political situation there, if it comes from abroad, is dismissed as the result of a Western bias. This was again the response trotted out by the government spokesman in Delhi when he was asked about the banning of the recent BBC documentary, which covered the murders of Muslims in Gujarat back when Narendra Modi was the state’s Chief Minister, in 2002. An official from the Ministry of External Affairs said that the documentary reflected a ‘colonial mindset’. Less than a month later, in a heavy-handed display, Indian income-tax officials raided the offices of the BBC in Delhi and Mumbai.

When we were on our way back to Patna from the village, our car entered the town of Motihari. This was the town where Gandhi launched the satyagraha movement against the British. My son asked my father if he had memories of a childhood visit to Motihari. ‘Yes,’ my father said, ‘I came here in 1944 to get my coat stitched.’

My father began to tell my son that in the year 1892, his great grandfather, Bhikhari Kuer, had come to Champaran from Saran. As my father talked, I began to take notes. Bhikhari Kuer had five sons. His youngest son, Shrikrishna Kuer, had three sons, the youngest of whom, Amar Kuer, was my grandfather. I hadn’t before heard all the names of my ancestors that my father was reciting. Even as I was writing the names down, I realized that when my father was gone, no one would remember the details of our rural past. For my son’s children, or his grandchildren, my father’s name and, in time, my own name, might well be as remote to their lives as the name of my great-grandfather had become to mine. This wasn’t a good or a bad thing; it was the way time worked. It also meant that the face I had seen on all the billboards in Delhi and in other cities – at the petrol station, on billboards at each street-corner, in offices, in ads and in reports in every newspaper – wouldn’t be around forever. And that, at least, gave me some comfort.

All images courtesy of the author