If I’m unlucky on my way to work, I sometimes end up stranded at the central train station in Wanne-Eickel, a small town in the Rhineland. There’s not much to do there. There’s a DM, a Lidl, a Hornbach. So you can shop, at least there’s that. The only thing I know about Wanne-Eickel is that Heinz Rühmann’s parents once ran a pub in the train station, most likely serving hearty broths behind heavy curtains. Heinz Rühmann – the so-called actor of the twentieth century, Germany’s cinematic everyman (starring in ninety films) – died in 1994 at the age of ninety-two. He was a little too old to be Elena Helfrecht’s grandfather. Great-grandfather, that would be about right. The people’s actor. Our grandpa, Germany’s grandpa.

In the film Die Feuerzangenbowle (1944), Rühmann plays the mildly insolent middle-aged writer Johannes Pfeiffer. Sometime around 1900 (we never learn when, exactly), his friends convince him to pass himself off as a schoolboy at the local Gymnasium. Among the weird old hacks teaching alcoholic fermentation and other arts, the young and pithy Dr Brett stands out. A perfect nationalist pedagogue, he compares his students to saplings: young trees need to be bound to stakes in the ground so that they don’t sprout in every direction. Discipline is the tie that binds them.

Despite the film’s celebration of discipline, it wasn’t enough for Nazi censors in 1944. The teachers in the film – apart from Dr Brett – were a bit too easily lampoonable as figures of authority. The film was not permitted to be shown publicly. Teachers couldn’t be disparaged when they were in such short supply. On a January night in 1944, Heinz Rühmann boarded a south-bound sleeper train out of Berlin with a copy of the film. When he arrived at the Führerhauptquartier near Görlitz (present-day Gierłoż) in East Prussia, Rühmann hoped to convince Hermann Göring to allow the film’s release. Göring’s officers were given a private screening, which they greeted with cheerful enthusiasm. Cheerful enthusiasm being at least as rare as teachers at the time, Hitler green-lighted the film, which he had not seen; it opened in theatres the next day.

Some of the film’s actors never lived to enjoy its lasting success. They were conscripted as soldiers in the Wehrmacht as soon as they finished their gigs as pupils in the fictitious Babenberg Gymnasium. Dr Brett’s rendition of the film’s core symbol for German discipline didn’t include the purpose for which the young saplings were raised: to be cut down as needed. Elias Canetti in Crowds and Power (1960) refers to the forest as a potent symbol of the Germans:

The mass symbol of the Germans was the army. But the army was more than an army. It was the marching forest. There’s no other modern country in the world where feeling for the forest has remained as alive as in Germany. The rigidity and parallelism of the upright trees, their density and their number fill the heart of the German with a deep and mysterious pleasure. Even today, he seeks the forest where his ancestors lived and feels himself united with the trees.

That was how it was supposed to be. In 1936, the German forest made its star turn in the propaganda film Ewiger Wald (Eternal Forest), a moody black-and-white cinematic hymn to the German woods, with a voice-over to match it: ‘The “Die and become” of the forest is woven through history. The Volk, like the forest, stands in eternity. We come from the forest, we live like the forest. From the forest we craft Heimat and space.’ The film is now only available in state archives. Heimat, Volk: ideology-laden words, which are today best avoided. Space. Forest. It’s hard to find words in German to substitute for them. As phenomena, they persist. How can we do without them?

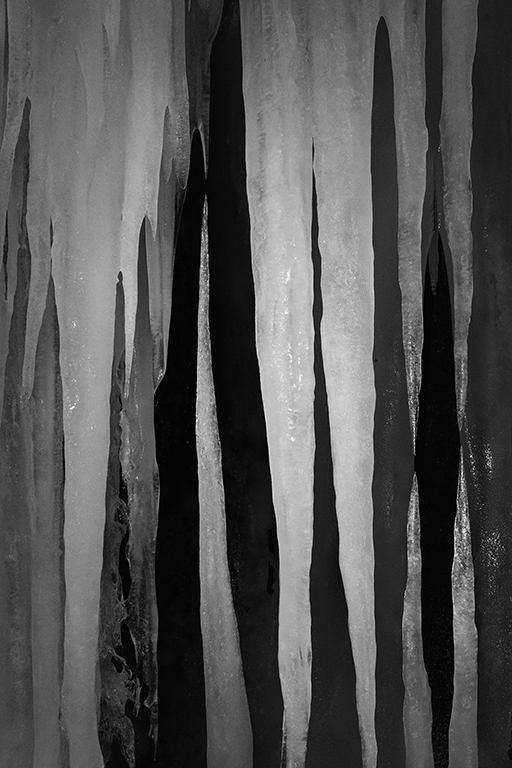

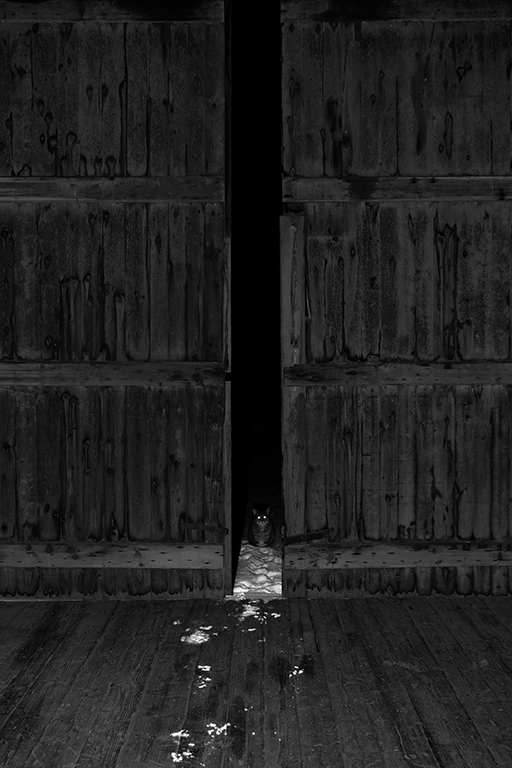

Elena Helfrecht’s images don’t depict horror, crimes or violence. And they don’t contain any people. They present the forest as people left it. It’s not a forest into which the sun shines brightly or where lilies extend heavenward. There is snow and it is night. These images don’t know Christmas. Helfrecht’s forest is a place where dead wood has taken on the form of a woman, where we stare wild animals in the eye, where we suspect body parts may be hidden under the snow. Icicles descend – but from where? From the roof of a barn where a cat seeks sanctuary? Maybe there was a hunt nearby. Two wings (from a swan?) hang from hooks in a tiled utility room. The stories that took place here might only have their full effect if they were intoned by Werner Herzog.

Helfrecht does not depict the orderly forest that Canetti describes as an effective German mass symbol. There’s nothing rigid and parallel here. Not a single tree grows straight and tall, as Dr Brett would have insisted. In Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen (1924), the young Siegfried rides to his fate between enormous, straight trees, grown parallel to one another. The most German of all German forests is a stage, a fantasy that promises death.

Helfrecht’s alternative imagery of brush and undergrowth are fostered by the knowledge of this dreamworld. Time and again, crosses appear in her photographs – perhaps more than are strictly necessary to understand that, for Helfrecht, these are spaces of death and trauma.

The forests in these images are crime scenes. Helfrecht’s subjects – the roots of a tree, a cat, the wings of a dead bird – all appear caught by the flash of her camera. The proverbial deer in the headlights is here, too, and apparently sees everything that the images only indirectly reveal to us. One of the signature features of Helfrecht’s work is that it tracks a past that she herself did not have to experience. The sense of menace unfolds quietly, its effect only heightened by its invisibility. The images make viewers, however unwillingly, into hunters, following the traces that Helfrecht has set out for them in the thicket of the past. But she does not guide us; there is no sense that we will make our way out.