What are you going to do with my furniture when I’m gone? my mother asks me. Oh, I say, we’ll see. It’s worth a lot, you can sell it. Let’s see what happens, I say. You’re attached to it, aren’t you? I don’t say anything. You know we even changed your diaper on the table here. I don’t say anything. But it won’t fit in your apartment. No, I say.

It’s not going to be easy to sell my apartment, my mother says. Don’t be silly, I say. The neighbors have been trying to sell theirs for six months and they still haven’t managed. Now they want to rent it out. Ah, I say. It doesn’t even make sense, it’s really nice here. No, I say, it really doesn’t make sense. It’ll be quite a hassle for you, my mother says. I don’t say anything.

My mother says: We have to go to the bank, you need to be authorized to access my account. I know, I know, I say. It’s important, she says. Yes, I know, I say. When do you have time – this Thursday? No, I say, I won’t be here on Thursday. Next week, then? Yes, I say. When? my mother asks. I tell her I’ll have to look at my calendar first. My mother says: Okay. A few weeks later she tells me: I didn’t even need your signature, I just had to give them your name.

So when my mother dies, I’m already authorized to access her account. I can use her account to pay for her funeral and the funeral repast, the gravestone and the cemetery fees, I can keep paying off the mortgage and the maintenance fees for her apartment, at least in the short term, while I try to sell it, and I can use a small trust that she left me to cover the monthly rent for the storage unit where I’ve had her furniture moved.

I choose an urn. I choose a spray of flowers. I choose rose petals to scatter into her grave. I hire a speaker to deliver the speech that I write for my mother. I have her mail forwarded to me. At first the forwarding request can’t be processed, because I’ve forgotten to enter my own name in the ‘care of’ field. An understandable mistake, since the only reason I’m filling out a forwarding request in the first place is that I’m no longer taking care of my mother. I have to submit the form a second time, and this time I write my mother’s name, care of my name. I cancel my mother’s subscription to the daily newspaper that she always read while drinking her afternoon tea, I receive a confirmation that the remaining balance of €202.07 will be refunded. The reason given for the cancellation is: deceased. I send my mother’s rail discount card back, the railway company refunds €91.66 of the €110 that my mother had paid two and a half months earlier. I have her telephone service cut off and request that her name be removed from the telephone book. Her final bill, the balance for her last phone calls with me, comes to €16.99. I cancel my mother’s account with the radio and television fee collection center. ‘This user’s account will be terminated at the end of the month. This user’s account has no outstanding balance.’

On the morning when my mother is cremated, I spend two hours sitting at home, in front of the window, on the chair where she always sat, waiting for the time to pass.

I cancel my mother’s membership to the General German Automobile Association. I write an obituary that appears in the newspaper that she always used to read while drinking her afternoon tea. I receive €170.03 for the obituary.

By the time the tax office inquires what personal property and real property I have inherited – real estate, assets, securities, jewelry, carpets, gold or silver – six weeks have passed since my mother’s death. ‘All information regarding the value of the estate should reflect the value on the date of death.’ But the tax office doesn’t want to know if I inherited a half-empty pack of cigarettes, a bathrobe with a used tissue in the pocket, or a bouquet that wasn’t even wilted yet. They also don’t want to know if I inherited my shoe size, my voice, or the way that I bend over when I put on stockings from my mother. They most certainly don’t want to know if I inherited the recipe for meatballs in creamy caper sauce, the straw Christmas tree decorations, or the rummy game with score cards from all the games we played in the past five years, each score written down with the corresponding date. The NS 17 form, which is used to calculate inheritance tax, also doesn’t have a column for the 10 bottles of shampoo and 10 tubes of conditioner that I inherited from my mother. My mother bought them all at once in order to get as many golden customer appreciation tokens as possible from the pharmacy and give them to my son, her grandson, to play with. I wash and rinse my hair with that shampoo and conditioner for the next year and a half.

Eight weeks after my mother’s death, the artists’ social security fund sends me a bill for €1.42 for the last day that my mother was alive, since it was the first (and for my mother also the last) day of the month, but none of the employees of the artists’ social security fund would want to know that on that day I took the wet trousers and the wet shirt that the surgeon had cut off of my mother and hung them out to dry on my laundry line, and that I also inherited this way of hanging out laundry from my mother. ‘The remaining balance is too low to be automatically deducted from your mother’s account. Therefore we ask that you transfer this amount to one of the accounts listed below. Please include your mother’s insurance number with your payment.’

I find a stonecutter who makes very nice gravestones and give him the dates of my mother’s birth and death so that he can create a design.

And so I inherit a furnished two-bedroom apartment with 108 square feet of storage space in the basement. I inherit bookcases full of books, cabinets with drawers full of files, photos and notes, I inherit a storage closet full of bedding, cleaning products, tools, shoes, large pots, an ironing board, a laundry-drying rack, a broom and a scrub brush, I inherit combs, brushes, makeup, shower gel and creams, inherit dishes, knives and forks, bottle openers, inhalers, aspirin, flower vases, paper clips, diskettes, envelopes, I inherit 1 television, 10 stools, 3 tables, 1 bed, 2 sofas, 2 armoires, 1 cabinet, 1 wardrobe, 11 lamps, 1 chandelier, 5 rugs, 1 wicker chest, I inherit winter coats, diaries, records, I inherit 8 bottles of wine and 3 of mineral water, inherit 1 music box, inherit necklaces, rings and brooches, inherit frozen roasts and frozen zucchini, 2 cans of lentils, 1 half-stick of butter, 1 lemon, 3 pots of probiotic yogurt, inherit 1 bicycle, 1 lawnmower, 1 washing machine, 1 Biedermeier writing desk, 1 wing chair, 2 paintings, 12 framed pictures, 10 apples and 1 banana, some bread, I inherit pens and white paper, inherit twine, coasters and potholders, inherit coins and banknotes from every country imaginable, cardboard boxes of buttons and yarn, 1 large and 1 small sewing box, I inherit hundreds of slides and 3 projectors, inherit 8 ashtrays, 3 cartons of cigarettes, 1 old cassette recorder,

2 mirrors, I inherit 1 computer, 1 printer, 2 old laptops, 1 old monitor, extension cords and 1 toaster, I inherit 2 houseplants, several bedspreads, wool blankets, pillows, inherit empty suitcases, inherit handbags and slippers, nutcrackers, Christmas lights, Easter bunnies, Christmas stockings, 2 boxes of Blue Onion porcelain, tablecloths, towels, eyeglasses, inherit sweaters, stockings, blouses, underwear, inherit cardigans and neck scarves from my mother. I also inherit my own suitcases full of winter clothes that I always kept in my mother’s basement in the summer, and my own baby clothes, as well as a little board that I painted when I was in preschool, 2 boxes of stones that I collected as a child and my small Chinese parasol.

After half a year has passed, people begin to ask: Are you writing anything new? No, I say, not yet.

Six months after my mother’s death, I pay the bill that the insurance company sent for the ambulance that took my mother to die, €30. I cancel the insurance policy for my mother’s fifteen-year-old car, and give the car to a friend. I hire a real estate agent to handle the sale of my mother’s apartment. The maintenance fees and the mortgage for the apartment come to €750 a month. In order for my mother’s apartment to be sold, it has to be empty. I start packing boxes. At home, I sort through my own books to make room for my mother’s books, papers and photo albums. That winter, I arrange the first move; two movers bring my mother’s desk, a cabinet and a trunk to my apartment. The day of the move is icy, and I’m glad that the men don’t slip as they’re carrying the heavy furniture.

In January 2009, I learn that the manager of my mother’s apartment building has run off with so much money that the electricity and water for the whole complex are about to be shut off. To prevent that from happening, the owners’ association votes that all members will make two special payments in addition to the regular maintenance fees, in order to ‘ensure liquidity’.

My mother’s apartment is very nice, but no one buys it, probably because it’s too deep in the east side of Berlin, in Weissensee, on the road to Moscow. I send an email to about a hundred friends and acquaintances. No one needs an apartment. I wake up at night haunted by fear.

I go to the stonecutter’s shop to inspect his design.

My mother’s tax advisor asks me to prepare my mother’s tax returns for the months of 2008 when she was still alive. I take a linen chest and various boxes out to our cabin in the country. When I’ve packed my mother’s books, some of the boxes go to my apartment, some go to the antiquarian bookstore, some go to the country. In my search for potential buyers for my mother’s apartment, I put up flyers at an art academy in Weissensee. None of the professors needs an apartment.

People ask me: Are you writing anything new yet?

In the process of closing my mother’s bank account, I realize for the first time that she also had liability insurance. Unfortunately, I am informed, the payments that have been deducted from her bank account for the entire time that she was already dead cannot be refunded. That spring, barely a year after my mother’s death, I rent a small truck and hire two students. We take 10 boxes, the bicycle, the lawnmower and various kitchen utensils to the country. On the drive out and back, we talk about film. That spring, the electric company, which has been providing electricity to my mother’s empty apartment for the past nine months, refunds me €119.81. The apartment still costs €750 a month. I decide that if all else fails, I’ll rent it out for now, and I place an ad in the paper. Around that time there’s some misunderstanding with the phone company, my phone stops working for weeks, and eventually the internet connection goes out, too. My apartment ad appears in the paper, but the phone number that I provided is out of service. In order to sell some lamps, my mother’s bed and her TV console on eBay, I have to sit in an internet cafe. While I’m there, I also send emails to the doctors in all eight departments of the hospital in Weissensee, offering them my mother’s apartment. None of the doctors needs an apartment.

When an employee at the bank that gave my mother the loan for her apartment hears that I’m planning to rent it out, she advises me that the bank is a public development bank, which means that I’m not even allowed to rent out the apartment on the open market, that is, I can’t charge the normal rent, and I have to receive special permission for each tenant. She advises me to refinance the loan.

I inspect the gravestone. The inscription will be colored in with brown paint.

The next move, early in the summer – this time with a moving company – makes its first drop-off at the storage unit, where I leave 1 sofa, 1 cabinet, 3 shelves, 1 armchair, 2 chairs and some boxes. From the storage unit we proceed to my apartment, where I unload some more boxes, a chest of drawers and some pictures.

I hire a second real estate agent to handle the sale or rental of the apartment. He advises me to clear out the very last items that are still sitting or lying around, at least to move them down to the basement for now. I should also take down the curtains and then have the apartment painted.

You must be working on a new book by now, aren’t you?

Since a self-employed writer would never be able to get a loan in Germany these days, I spend time negotiating with my husband’s Austrian bank about refinancing the loan before my son’s school lets out for the summer. The loan is approved, with my husband as guarantor.

I clean everything out of my mother’s freezer and pull the plug out of the outlet. Now, for the first time, the apartment is completely silent. I take the frozen food that my mother cooked, carry it home in a well-insulated bag and stash it in my own freezer.

The gravestone is finished now, it’s installed in the cemetery. When she finishes her calculations, my mother’s tax adviser tells me that my mother is owed a €5 tax refund. My telephone is working again. The internet is working again. On the day in autumn when I finally clean out my mother’s apartment once and for all – clean it so thoroughly that not even a bit of thread or crumpled newspaper remains – on that day, when I take my mother’s slippers, the scrub brush, the whisk broom, the dustpan and the toolbox down to the basement, when I carry the ashtray with the last cigarette that my mother ever smoked to my car (later, on the drive back to my apartment, the ashes that my mother tapped into the ashtray will crumble), on that day I run into my mother’s neighbors in the hall. When they hear that I’m open to renting out my mother’s apartment rather than selling it, they say that they’d be interested. A few weeks later we reach an agreement.

Now I’d like to call my mother.

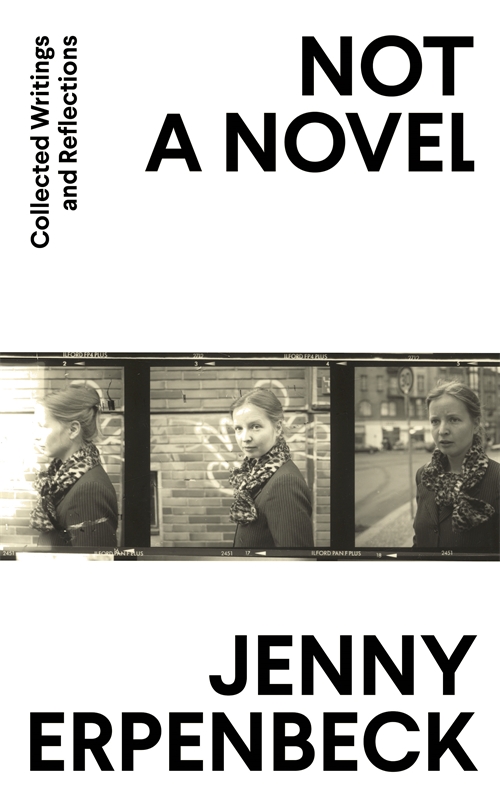

Photograph © Katharina Behling, Jenny Erpenbeck (right) and her mother Doris Kilias, 1999

‘Open Bookkeeping’ is included in Jenny Erpenbeck’s Not a Novel, available now from Granta Books.