When Walt Whitman walked through Brooklyn Heights – a sharp-aired morning, say, in the newly minted spring of 1855 – headed toward the printing office of his friend Andrew Rome, did he know what he was carrying? I like imagining him, a large, roughly handsome man who appears older than his thirty-five years, the sense of purpose in his stride more pronounced as he approaches the shop at the corner of Fulton and Cranberry (an intersection that no longer exists, since the two streets were reconfigured, in the twentieth century, with the creation of Cadman Plaza). I picture a portfolio under his arm, pasteboard sides covered in cloth like the green binding he’d choose for his first edition, a ribbon closure tied to keep the pages in place. Around him the traffic of shoppers and deliverymen, errand boys, a few finer carriages, horse-carts clattery and pleasingly fragrant, vendors’ voices darting between the open spaces in each other’s repetitive declarations of what’s for sale. Brooklyn brisk with possibility, sky rinsed a powdery blue. Adventurous little wind from the harbor, a chill still lingering on the shaded sides of streets. Ordinary business: the world as it constructs itself day after day streaming by.

Do his steps quicken or slow as he draws nearer the printer’s door? Some acquaintance greets him as he passes, but the poet barely notices. His attention is fixed on the brink on which he’s poised, the condition of about-to-become–himself. In a moment a wave of potential, the expansive dreaming overflow of his text, will crash against the marble threshold and begin to become a singular fact: his longed-for, dreamed-of book.

*

When I was twenty-five, I went to a writers’ conference, my first, on the California coast, on an Edenic Santa Cruz campus of yellow grassland pouring down the slopes to the sea. There were workshops and readings, and a good deal of staying up till one could drink no more, convivial nights of long talks – most often about our wish to become ourselves as writers, whatever that might mean, about longing, our deep desire to feel complete, real to ourselves. I made a raft of friends: a lean and intense fiction writer trying to find her way inside a novel that eluded her; the West Coast editor of Playgirl, a joyful, zaftig beauty who wore metallic caftans and shared with me her delicious, slender little cigars. It was 1978, I was still married, and secretive about my longing for men, but I had a mad crush on a warm, bearish man whose every gesture seemed to spread sweetness and good humor; like the Playgirl editor, he occupied space with notable delight in being a body. Toward the end of the gathering he told me, in an embrace flushed with wine and heat, that if he hadn’t been having an affair with the woman across the hall from my room he’d have been with me. That would have been possible? I was dazed, and so happy with the idea that such a thing could have happened I honestly didn’t mind so much that it hadn’t.

There was another set of events, too, richer and stranger. The poet William Everson – the elder, animating spirit of the place, who had once been Brother Antoninus, a Carthusian monk who renounced the order to pursue both art and pleasure – offered a series of meditative lectures, a loosely structured performance over several mornings called ‘The Birth of a Poet.’

At an hour on the early side for apprentice writers, still groggy, we would troop down the hill toward a space deemed conducive to inwardness. Could it really have been called the Kiva, or have I invented that the way I have Walt Whitman’s wide-awake stroll in that splendid Brooklyn spring? Everson himself was Whitmanic: streaming white hair, generous beard and eyebrows to match. He wore old jeans and a shearling vest over his white shirt, fleece turned inward against the coastal damp, the leather beaded and sketched in dark lines with animals and stars. It had been given to him, he said, by his friends among the Kiowa. In one of the two pockets in front resided a smallish bottle, a pint of the Jack Daniel’s he would not be without.

Much of what he said I’ve forgotten. Certainly he described his spiritual vocation, how the calling to the monastic life and the calling to poetry were in fact the same thing, perhaps misheard at first, understood differently over time. He talked about his hero Robinson Jeffers, the great poet of that coastline, a fierce and lonely man with a touch of granite both in his profile and in the chill around his heart, who lashed out at his own species and wrote of beautiful ‘hurt hawks’ because he could not bear the pain we inflict on one another, or the injury that must have been done to him. As great poets do, he found a way to transmute the personal wound into something larger. His rejection of human company became a way to love stone and wind and time, the grand elemental forces made visible on the bluff in Carmel where he built his own stone tower of a house. The surf and stones of Big Sur, if not larger than time or quite outside of it, were of a scale commensurate with the ages. I used to think I could never take pleasure in imagining the earth after the Anthropocene. But as the damage we’ve done grows clearer every day, I find myself in greater sympathy with Jeffers’s position; his poems take comfort in the world going on without us, our petty scrawlings on the face of the planet all swept away. Even stone towers? Probably.

Like Whitman, Everson was also a printer. He told us about his printing press, the cold metal of it, the way setting type brought one closer to the body of the poem. How he’d made an edition of Jeffers’s poems, each copy housed in a case of Monterey cypress; into the cover of each he’d inlaid a polished square of granite from Tor House itself. Many sips of whiskey between all this, pauses while Everson waited for the next thread to come clear. A little shuffling, circling dance, some coughs, some pacing, a sip of whiskey, and in a while a new direction emerging from the last.

Here is what he said that I’ve never forgotten. The movement of the soul is vertical, he claimed, descending into the world, and when we become incarnate, as Christ the model and exemplar of the human form did, then our vertical motion intersects with time, with the horizontality of the temporal world. When a book is made, then, the life of the maker is nailed, as it were, to the intersection of those two lines. In the book, he said, the self is fixed, made concrete; the book is the intersection of the soul and time.

*

In a quiet room for researchers at the Library of Congress, on a quiet August afternoon, I sit at a table alone while a helpful and solicitous librarian – glad, I think, for those thrilled by the proximity of great books, the intersection of the soul and time – brings me a copy of each of Whitman’s first editions. I open the cardboard slipcover of the first, and hold in my own hands the oversized, thinnish, slightly unwieldy book, set it down into the foam cradle the librarian has provided, open the cover, and turn to the first page of the first poem. The hands of a man I love, dead so many years before I was ever born, have touched this page, and set these letters into type. In the blank space between stanzas, I can feel the forward motion of his thinking slowing, seeming to pool here, gather, until it spills over into the next stanza. In some places the type is ‘broken,’ a printer’s term for when the ink does not fill the black form of the letter evenly; a hairline crack of white shines through, or a dapple of bare paper’s left visible. Sometimes a little extra bit of ink pools at the top of a letter, or in a period. I know it’s the mechanism of printing that has made these rough marks, making this page feel handmade, allowing me to touch the letters and feel their impress into the weave of the paper. (Don’t be alarmed, the Library doesn’t ask one to wear gloves. Gloves have been found to do more harm than good when handling archival material.) A poet, Whitman wrote, in the preface to this 1855 edition, glows a moment on the extremest verge. It seems to me that glow is pouring through this page, from behind it, even through the broken type, so bright the words seem nearly tattered and burned by it.

*

The author of those pages had a third-grade education, if the endless recitation of drills that comprised Brooklyn public schooling in the 1830s can be called that. At eleven, the age around which many boys of his era began to work and learn a trade, he apprenticed to a printer. In the years before the publication of his book he’d work as a printer and journalist (a common combination at the time), an itinerant schoolteacher in small Long Island towns, a bookseller, a carpenter, a builder of houses. Had he died before that curious, oversized first edition of Leaves of Grass was published, it’s unlikely we’d ever have heard his name.

You’d think something in the early work of Walt Whitman would suggest the intelligence and scope, the sly wit and visionary luminosity of the pages stacked and wrapped in his ribboned portfolio. When he made his agreement with Andrew Rome he was thirty-five, and his publications consisted of a handful of forgettable poems and a larger quantity of windy prose: editorial pieces, melodramatic short stories, an urban mystery serialized in newspapers, and a clichéd temperance novel. But there’s nothing at all to make us suspect that this man will write a decent poem, much less reinvent American poetry. He would pay to publish his book, write many of the reviews of it himself, sell precious few (if, in fact, any) copies, and then go right on to publish a second edition. Who’d have thought it would be a book that we have never finished reading? One that would be translated into every language in which poetry might be read, a book people scattered around the globe are holding at the moment you read this page. One he never finished writing, but simply revised and expanded until it was stretched, some thirty years later, into a lumpen thing, almost beyond recognition. A book of presumption and daring, expansiveness and wild ambition – one with a few antecedents, yes, but nonetheless startlingly original, unlike anything that had been written before.

Where on earth did it come from?

You can ask that question of any poem, and one inevitable answer is a simple one: work. No made thing springs up unbidden, even those that seem to. The poem that announced itself to the intoxicated Coleridge, before a knock at the door banished most of it from his memory, or the composition that sprung full blown into the head of Mozart, as he stepped down from a carriage after a satisfying dinner, seemed to pour from the artist’s hand, so long schooled those hands had become. But years of labor inform those spontaneous productions. Though a poem over which one struggles may seem labored, it often prepares the way for new writing in which what’s been learned emerges with an effortless grace.

In the end, though, work accounts for a poem of genius about as much as plumbing accounts for the fountains of Rome; it yields a necessary basis, the practical scaffolding that underlies the whole, but cannot in itself engender a sense of transport. To shift the figure from water to another element: labor may give a poem a ruddy glow, but no amount of it will set the page on fire.

The great poems of Leaves of Grass are spectacularly, uniquely on fire. There are, I admit, only a handful of them, although one is long enough that you can wander in it like a labyrinth, uncertain of where you’re headed, but gradually, undeniably arriving someplace entirely new. The brilliant midcentury American poet and critic Randall Jarrell wrote that ‘a good poet is someone who manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms, to be struck by lightning five or six times; a dozen or two dozen times and he is great.’ Who besides Shakespeare might have been struck by lightning two dozen times I cannot say; even in the life’s work of many of our greatest poets, a few dazzling, electrical flashes are brighter than all the rest. We think no less of John Keats because he didn’t write more of those odes, or of Elizabeth Bishop because her final collection, Geography III, wasn’t longer.

And what daring, heat, and light Whitman’s masterworks emit! They proceed with absolute confidence to make the wildest claims, inventing a cosmogony, a theology, a stance toward reality. They burn with evangelical urgency yet insist that no one requires a spiritual teacher. They find the basis for a social compact in the common bedrock of the desiring human body, and sing the inclusive, generous, common self in a mode so formally inventive that its first readers must have wondered if this was poetry at all. The combination of unbridled content and unfamiliar form seems to have left even readers of undeniable acumen in the dust. Emily Dickinson is said to have taken a peek inside and then firmly closed the book; Henry James noted, with devastating simplicity, ‘This will not do.’ I would like to think that writers of such genius, whatever they may have said, recognized as kin the astonishing outpouring of work that appeared from the hand of a self-educated ‘rough’ from Brooklyn, but there is no evidence that they did. There is surely an uncomfortable sort of admiration and kinship expressed in a letter from the great, tormented Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins though: I always knew in my heart Walt Whitman’s mind to be more like my own than any other man’s living. As he is a very great scoundrel this is not a pleasant confession.

*

How could this strange book not have offered to its author a hundred separate possibilities for uncertainty, even for doubt of a particularly corrosive, self-lacerating kind? A book with no author’s name on the cover or title page, with a densely printed, rather florid preface followed by twelve poems. Were they poems? No consistent meter, no comfortable and familiar pattern of rhyme. Not to mention the fact the book’s opening salvo is a dizzying sixty-five-page text, the sheer rock-wall of it divided only by stanza breaks. The sweeping lines, colloquial and Biblical at once, seem meant to carry us from earth to – well, not heaven exactly, but the earth seen in radical illumination. I believe a leaf of grass, he writes, is no less than the journey-work of the stars. He mocks religion while proclaiming the world holy. He loves being incarnate, relishing sheer physicality – to walk, to feel the movement of atmosphere on one’s skin – and the thrilling energies of eros, the firefighter’s fine muscles moving under their clothes. His feints and silences are so transparent that they reveal at least as much as they conceal.

Here’s a quick example. The speaker, at the end of one stanza in ‘Song of Myself,’ is thinking about the way he moves among those who remember him:

Picking out here one that shall be my amie,

Choosing to go with him on brotherly terms.

Then we have. a stanza break, and look where the poem goes:

A gigantic beauty of a stallion, fresh and responsive to my caresses,

Head high in the forehead, wide between the ears,

Limbs glossy and supple, tail dusting the ground,

Eyes full of sparkling wickedness . . .

That’s a perfectly accurate description of a spirited horse, but it comes just a bit of white space after brotherly terms. It’s useful to remember that ‘stanza’ is Italian for ‘room,’ and that as we walk through the rooms of a poem, our experience of each space colors our perception of the next. Responsive to my caresses, glossy and supple limbs, eyes full of sparkling wickedness: surely the poet’s sexy, playful description of this gigantic beauty is intended to make us read those brotherly terms in a new light.

What the poet is doing here doesn’t quite qualify as hiding. A reader uninterested in – or unaware of? – same-sex desire could simply miss it. That simple stanza break allows us not to tie that animal body to a desiring human one if we don’t want to. The poem plays on a sort of margin; I think it’s fair to say that Whitman is enjoying this game, sporting in a mode of self-disclosure which will be read clearly by those who want and in fact need to read ‘between the lines.’ What scandalized readers in Whitman’s time was his frankness about heterosexual bodies, and his portrayal of women as sexual beings. Only those alert to samesex desire seemed capable of reading a deeper level of scandal in the poems, a ‘secret’ – shared in broad daylight but largely unreadable – that was for them more nourishing than any other text of their time.

This peculiar, daring book, not even finished that morning when Whitman carried his manuscript into the printer’s office, still to be added to, and quickly revised, and at odds in form and content with essentially everything in print in its day – how could it not have racked its author with uncertainty?

I am not sure if, during the trance of composition in which Whitman wrote the greatest of his poems, he entertained a doubt at all. ‘Song of Myself’ offers no evidence that he held a single reservation, or feared that he could not say what he needed to. (He does at one point doubt the capacity of language to say what he means, but that is not the same thing as mistrusting one’s own ability to use it.) In the 1855 edition, the poem doesn’t yet bear the title the poet would later settle on; it’s not clear that it has a title at all. It swells, drifts, eddies and circles back; its pages are divided into stanzas, but no section breaks divide the reading experience into manageable units. The reader’s tossed headlong into a cascading, seemingly edgeless text in which it’s nearly impossible to find one’s bearings.

Mornings over the first few months Whitman would appear at the printer’s office, read the paper, talk, assist, and in between commercial jobs, set at least some of his own pages in type. Andrew Rome’s brother and business partner James had died just months before, and the aggrieved printer must have welcomed the company. His shop mostly printed legal forms of one kind and another, and when in July he issued the company’s first book, oversized, its pages resembled the paper they must have also used for wills, contracts, and promissory notes. Two hundred copies, and then eventually some seven hundred in all, would be carried to a nearby bindery, a few bound in paper, the rest stitched, glued, and bound in green cloth, with the letters of the title stamped in gold: Leaves of Grass.

*

The thin, oversized book was, to put it plainly, weird. It was bound in green cloth, and stamped in gold with roots, branches, and grain woven together to form the letters of the title, in imitation of a popular book, Fern Leaves from Fanny’s Portfolio, by Whitman’s friend Sara Willis. Under the name Fanny Fern, Willis published newspaper columns widely read by and circulated among women at midcentury. So widely, in fact, that her first book had sold some seventy thousand copies, from which she earned a dime apiece – enough to land her financial independence and a townhouse in Brooklyn. Whitman admired her, not the least for her success.

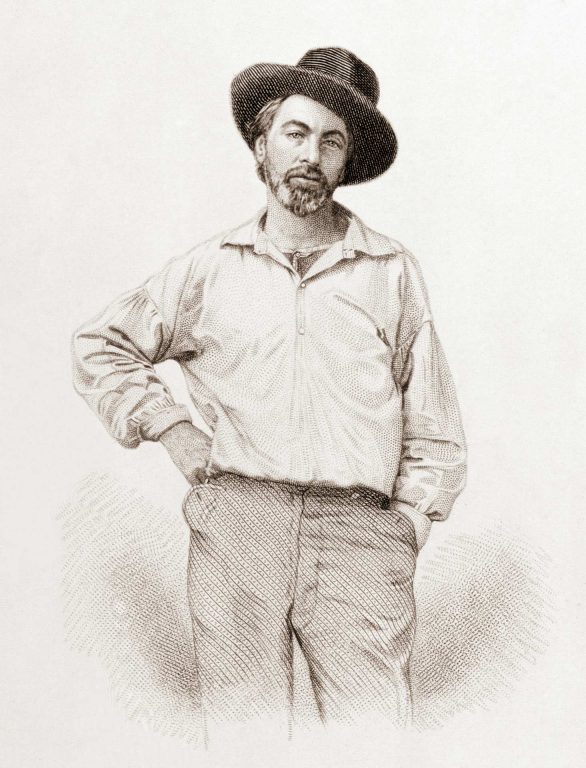

Open Whitman’s book, and after the obligatory white page (a visible moment of silence) is the engraved image of a man, not one a poetry reader of the time would have expected to meet. No gentleman in serious clothes, authority backed by laden bookcases, maybe a classical bust looming behind. No romantic in a loose cravat looking dreamily toward the empyrean, tethers to earth loosened by fevers or opiates. Instead, this:

The engraving was based on a photograph of Whitman now lost, which is unusual in that he was photographed often, and carefully saved these images. Here he’s a slouch-hatted workman, outfit and demeanor radically informal; his undershirt shows behind his open collar. It isn’t easy to name the attitude his facial expression and posture convey. Certainly there’s a relaxed quality in the tilt of the pelvis, the easy way his shoulders fall, and the slouch of the hat. But the angle of the face, the narrowed eyes and slightly raised eyebrows have a quality of assessment about them. Is he taking our measure? You could take that hand on the hip as a cocky gesture, as if he’s looking us up and down and saying, Well, who are you? Affectionate, haughty, electrical, he writes, I and this mystery here we stand.

Haughty and electrical I can see, but affectionate? Not a quality this image suggests, but what I’m reading as an evaluative gaze may in fact be a not altogether successful representation of something else – the look of one still dreaming, the way new infants sometimes seem still to gaze upon something they’ve not yet fully left behind?

No author’s name is given, on the cover, spine, or opening pages, save for, in the tiniest of italic fonts in the center of an Anarctic page, these words: Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1855, by WALTER WHITMAN, in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United State for the Southern District of New York. You have to reach page 29 to find Walter Whitman’s new name, the name of the man he became to write these poems: Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos. Imagine self-publishing your first book and not putting your name on it! Asked about this oddity years later by his worshipful young secretary Horace Traubel, the elderly poet replied, I suspect quite sincerely, ‘It would have been like putting a name on the universe.’ In other words, he is not, in the usual sense, the author, or not entirely so; Leaves of Grass is a kind of collaboration with totality, and Whitman believed wholeheartedly that it was given to him. Although disguised as a volume of parlor verse in its decorous binding, the book was from its inception a provocation, an assault, an outcry, a gospel. I like to imagine those pages, before they were set into type, the energy not yet released from them compressed until it would explode, in a movement that continues unabated as I write, one hundred and sixty-four years later.

This essay is included in Mark Doty’s What Is the Grass, published by W.W. Norton.