The mournful dirge flows out from the loudspeakers in a continuous stream, traveling slowly through the downtown streets where the rain keeps on falling. Its leaden cadence even filters into the meeting room of the municipal security department, adding further bleakness to the already subdued atmosphere.

To those gathered in the room, the announcers’ voices seem unusually deep and clear, and they fancy that they see tears streaking down from the ceiling. The sound of the rain, the sound of the wind . . . Looking out beyond the window, its glass blurred by a solid stream of rainwater, they see the trailing tendrils of a gnarled old willow whipping through the air like a nest of snakes. When the wind pauses to gather its breath, its absence amplifies the sound of the rain, which pours down the roof in a plaintive whoosh.

All of these things taken together seemed an apt expression of our nation’s mood, throwing the word ‘mourning’ into stark relief. Those of us sitting here in the meeting seemed to be caught up somehow in a scene from a play, out of kilter with the real world.

The atmosphere of the meeting had built to a distressing tone, which caused us all to fall silent for a time. Now, when the director of the secret services, the Bowibu, shook himself and resumed his address, his voice sounded shrill and somewhat tinny in contrast to the measured, plaintive tone of the announcer.

‘Now that every flower bed in this city has been stripped bare, now that we have risked poisonous snakes and landslides to bring further tribute from the fields and mountains, can we say that our Great Leader has been suitably mourned, sit back and rest assured of our loyalty? Absolutely not! Not when the very behavior we exist to stamp out has reared its ugly head within our own Bowibu family. In these tragic days, when even drowning ourselves in our own tears would not express the depth of our sorrow, there are those who sneak off to drink and flirt under the pretext of picking wildflowers!’

The Director, still clutching his tear-soaked handkerchief, brought his fist down on the lectern with such force he seemed to want to smash it to pieces. The wood shuddered in protest, and there was a perilous moment when the glass of water bouncing on its top seemed about to capsize.

‘This point has already been emphasized, but you must remember that while our Great Leader’s funeral is still in progress our agents must exercise the utmost vigilance, keeping their eyes and ears peeled at all times, their fists clenched and at the ready. And you must instill this necessity in them. Only then will we avoid falling victim to any further goblin trickery. I cannot stress this point enough. Well, that will be all for today.’

The Director underlined his words by sharply clapping his journal closed, then followed that with a more restrained rap on the lectern. ‘Comrade Inspector for the Union of Enterprises, come to see me before you leave.’ This was spoken relatively quietly, but still loud enough to reach the ears of everyone in the room.

A stunted man sitting near the window turned to his bespectacled neighbor. ‘Did I hear right?’ he murmured. ‘The Union of Enterprises?’ His name was Hong Yeong-pyo, and his title was the very same that the Director had just called out. His neighbor nodded in confirmation, and Yeong-pyo abruptly felt several dozen gazes trained on him, as if he were caught in the beams of a battery of searchlights.

So it was you the Director was alluding to just now, when he said ‘within our own Bowibu family’! The message of those sharp eyes was loud and clear. As Yeong-pyo stepped forward, the words ‘to drink and flirt’ echoed in his ears, and the face of his son Kyeong-hun swam queasily into his mind.

As soon as Yeong-pyo was standing in front of him, the Director waved a piece of paper in his face. ‘This came straight from one of our agents,’ he snapped, his voice stinging like a slap. ‘During the period of mourning for our Great Leader Comrade Kim Il-sung, Union of Enterprises employee Hong Kyeong-hun went to gather flowers in the foothills of Mount Baekryeon, where he was seen holding hands with factory girl Kim Suk-i –’

‘Kim Suk-i?’ Yeong-pyo broke in, unable to restrain himself.

‘That’s not all! Holding hands, and also drinking alcohol. I have the evidence right here.’ He jerked his chin in the direction of a small plastic bottle on the desk next to Yeong-pyo. ‘It was still reeking when the agent brought it to me. Go on, smell for yourself.’

But for Yeong-pyo, the issue was not one of alcohol. Kim Suk-i? Which Kim Suk-i? Surely not the elder girl, whom everyone called ‘Big Suk-i’. Little Kim Suk-i, then? Let the Director be ignorant of that at least!

Luckily, the Director had a different interpretation of the horrified look on Yeong-pyo’s face, imagining his subordinate to be aghast at the thought of having questioned his superior. ‘Quite right,’ he said, in a slightly softer tone, ‘the evidence of the report is perfectly sufficient. So what do you think, Comrade Hong: Can this be classed a general incident, or is it a political matter?’

‘Of course it’s political. Such behavior would be disgraceful at any time, but now! Now, when the inestimable loss of our Great Leader . . .’ As though on cue, tears ran down Yeong-pyo’s cheeks, sallow and sunken owing to a long-standing liver complaint. Even Yeong-pyo himself found it difficult to comprehend. How could the small cup of sadness sitting inside him produce a whole pitcher’s worth of tears? But shedding them right now, in front of the Director, made them truly worth their weight in gold . . .

‘That’ll do, that’ll do.’ The Director, too, sounded somewhat choked, though he quickly recovered himself. ‘You know, Comrade Hong, the recommendation was to come down hard on this. But your feelings on the matter are clearly not to be faulted. You don’t need me to explain the severity of the incident, and in any case, we went over all that in the meeting.’

The Director softened his tone even further, sympathizing with this man who was so clearly ravaged by disease, and who was after all one of his own. ‘There won’t be any official sanctions. I dealt with the report personally, as it concerned our Bowibu family. Go on, and take that bottle with you. Use it to bring your son to his senses.’

‘Thank you. Thank you.’ Bowing twice, Yeong-pyo left the Director’s office.

The rain and wind were still as strong as they’d been at the start of the monsoon. A knot of people stood outside the main door, huddled under the awning in the hope of even a brief letup. Yeong-pyo pushed past, out into the street, muttering to himself that it was all right for some.

Each step threw up a splash of muddy water, while thin streams of rain poured over his chin. His armpits began to prickle with heat, a sign that his worked-up mood had provoked his liver, which had begun to harden as it lost its battle with the disease. But Yeong-pyo rarely had the luxury of attending to his pain. His son had an ‘incurable sickness’ of his own, and one whose remedy was far more urgent. As he walked, Yeong-pyo unconsciously tightened his grip on the bottle concealed in his trouser pocket, squeezing so hard that the plastic buckled. For the second time that day, a voice from the past echoed in his ears.

To bring your son to his senses . . .

But the voice wasn’t that of the Bowibu director; instead, it belonged to the director of military security, who’d spoken those same words – To bring your son to his senses – almost a year ago when Kyeong-hun had been demobilized.

Strictly speaking, your son should have been packed off to political prisoners’ camp, but I invented a ‘Fault 1 Demobilization’ instead. We’re colleagues, and I wanted to give you the chance to bring your son to his senses. I’ve enclosed his written statement with this letter; once you’ve read it, you’ll understand that further le niency simply wouldn’t have been possible, under the circumstances. This young man is more canny than he’s letting on.

Yeong-pyo had raced through the letter, then unfolded his son’s statement with a trembling hand.

I have been accused of a heinous crime against the Party and our Great Leader, General Kim Il-sung. My comrade from the security department claims that my brain has been rotted by the South Korean puppets’ anti-Communist broadcasts that parrot ideas of ‘freedom.’ I acknowledge the truth of this. It was while stationed as a border sentry on the 38th parallel, where I had been assigned in order to prepare for the military arts festival, that I was subjected to this constant barrage of ‘freedom’ propaganda. These broadcasts hounded me every hour of the day; there was nowhere to go to escape them, and nor was it feasible to go around with my hands over my ears. The crime of which I am accused was committed on Saturday evening. We had held a dress rehearsal in the presence of the director of the political department, and then received criticism for our performance.

‘Today’s rehearsal was extremely mediocre. I pride myself on being a man of culture, and I’ve attended enough plays and recitals to know what is meant by ‘stage truth.’ You might not be familiar with the term, but you should at least understand the concept, how actors perform a given play as though it were real life. To lie, in other words, but convincingly, so the audience will believe it is the truth. But was there anything convincing about the awkward, stilted performance I just witnessed? No, Comrades, there was not. Stage truth can be achieved only with complete mental and physical control. Has your training taught you nothing more than how to pipe a few tunes on a tin whistle?’

This was the comrade director’s evaluation of our performance. As punishment, we were ordered to do practice drills, and though there was a lot of grumbling at this, because the drills are exhausting, and we were already hungry, still we set to it in earnest. At ten o’clock the comrade director returned, apparently to check that we were doing the drills properly. It just so happened that my storytelling troupe were the ones on stage, while the rest were waiting their turn in the audience seats. The director watched us for a minute or so, then told us to take a break. Seeing us throw ourselves into the drills so wholeheartedly must have appeased his anger at our shoddy acting.

‘How do you find the drills?’ he asked. ‘Tough, no?’

‘It’s nothing!’ the troupe cried out as one. The only ones who remained sullen and silent were myself and Comrade Oh Haknam, whose father is a jidowon in one of the provinces.

‘You must be hungry, though?’

‘Not at all!’ came the answer. As if that wasn’t enough, Comrade Kang Gil-nam felt the need to yell out, ‘We aren’t gluttons obsessed with filling our bellies!’ and the rest of the troupe then bellowed their assent, drumming their heels. I was genuinely taken aback. This was the same Kang Gil-nam who, only a few moments ago when he’d stumbled during one of the drills, had been griping about how it was no wonder we were so weak, ‘living off chicken feed’. And not just him; back then the rest had been perfectly quick to join in, even cracking jokes about their navels being in love with their spines, as the two were clearly hankering for a kiss.

So how were they now contradicting themselves so convincingly? Might this be the ‘stage truth’ that the comrade director had talked about? I couldn’t say; unlike him, I’m no connoisseur of the arts. And wasn’t it even more bizarre that only Comrade Hak-nam and I, whose fathers are both high-ranking cadres, had been unable to join in this display of acting talent, instead presenting the comrade director with expressions more suited to a constipated dog?

In any case, after briefly exhorting us to carry on, saying we’d do well to apply the same effort to our rehearsals, the director disappeared back inside, out of the cold. He’d said he would be back again at 11 p.m. to settle up, but 11:30 p.m. and then midnight both went by with no sight of him. By this point, we were too exhausted and strung out to carry on drilling.

And so we all – storytellers, singers, and accompanists – huddled around the drum stove, which was a tight squeeze for forty-odd people, and which in any case was producing more smoke than actual heat, as we had only unseasoned firewood to burn. Some tried to make the time go faster by cracking jokes, but they ended up being pretty damp squibs; we were just too cold to be properly funny. Not that this mattered; as usual in such a situation, where gut-wrenching rage had to be forcibly suppressed, we were ready to fall about laughing if anyone so much as coughed a bit strangely. It was almost like some kind of laughing sickness.

Someone hissed at us to be quiet and we all pricked up our ears, thinking he’d heard the director’s footsteps; then a drawn-out fart ripped through the silence and we all roared our heads off. Though I laughed with the rest of them, in spite or perhaps because of our sorry situation, I could feel something boiling inside me. First, I couldn’t help suspecting that we wouldn’t have been abandoned for so long if it hadn’t been for foolish bravado. My feelings toward those comrades of mine who’d pretended to be immune to hunger and fatigue weren’t exactly benevolent. On top of that, it really was bitterly cold.

But worst of all was that I’d been assigned a skit called ‘The Bottomless Mess Tin’, meaning I’d had to spend half the night pretending to be devouring all manner of delicious things while in reality my stomach was as cold and hollow as an empty cellar. It really stuck in my craw, I can tell you. I whipped out a cigarette in a fit of pique, but no sooner had I stuck it between my lips than the drill leader decided we’d sat around for long enough and ordered us to ‘resume, starting with the comedy skit’.

Why that damned skit first, of all things? I thought, and before I realized what I was doing I was on my feet. ‘Never mind the skit,’ I shouted, bounding up onto the stage, ‘I’ll improvise something that’ll have you in awe of my stage truth.’ This was what had been building up inside me, straining to get out, and there was just no way to hold it in any longer. ‘Hmm, what shall I do about a title? I’ve got it! “It Hurts, Hahaha”, to be followed by a second act called “It Tickles, Boohoo”!’

While the others laughed at my antics, I slipped behind the stage curtains before turning around and poking my head out, making sure that only my face was visible. Even now, I can’t understand how something I’d dreamed up on the spot managed to flow so seamlessly. ‘Ladies and gentlemen!’ I cried. ‘At this very moment, behind the curtains where you cannot see, I’m being pricked with a whole host of needles. But the director commands me to laugh! Go on, one of you lot be the director.’

‘Laugh!’ someone shouted obediently, and I instantly responded by contorting my face into a grotesquely exaggerated mask of pain, stretching my mouth as wide as it would go before parodying, to the best of my ability, the spectacle of sobs gradually transforming into laughter, crying first ‘Boohoo’ and then ‘Haha’. The others were in stitches. They were still wiping away the tears when I popped out from behind the curtains and announced the second act. But I was interrupted by Kang Gil-nam, leaping up to join me on stage.

‘I’ll do Act Two!’ he announced, darting behind the curtains and poking his face out just as I had.

‘You, Comrade? Very well! Right, so this time . . . Got it! Ladies and gentlemen, allow me to introduce Comrade Kang, a budding actor in his twenty-third year of drama school.’

‘Nonsense, how can anyone be a student for twenty-three years?’ a female comrade called out.

‘Ah well, if you don’t know, I can’t tell you! This second act, as previously announced, is a piece by the name of “It Tickles, Boohoo”. Right! A soft set of fingers begin to inch their way up to Comrade Kang’s armpit . . . one step . . . two steps . . .’

‘Hahahahaha! Uh-uh . . . boohoo.’ As an actor, Comrade Kang was head and shoulders above me. The others were clutching their ribs and begging him to stop.

They say laughter is the best tonic, and the others did indeed appear all the better for our comic interlude. Once they were sufficiently recovered, it was back to the drills, and this time there were no complaints.

This account is a full and detailed explanation of my crime, a crime for which I humbly beg forgiveness. The broadcasts of the bastard South Koreans must genuinely have rotted my mind.

As to why I chose those particular titles for my improvised performances, something which the comrade director has asked me to clarify, surely it is not such an uncommon idea, having to laugh at something to stop yourself from crying, and vice versa?

Those were just the first titles that popped into my head, seeing how Comrade Kang and the others refused to admit to their hunger, and thinking of myself having to perform ‘The Bottomless Mess Tin’ while my stomach felt as though it might devour itself.

Second, as to why I described Kang Gil-nam as a twenty-third year drama student, again, it was the first thing that popped into my head, as Comrade Kang is twenty-three years old. This is the honest truth. I never would have dreamed that this foolish clowning of mine would be a matter for the security department. Again, I can only beg forgiveness.

‘You louse!’ The same exclamation that Yeong-pyo had spat out on first reading that statement now sprang once more from his mouth, awash with the taste of rainwater. It stood to reason that as the son of someone high up in the Bowibu, Kyeong-hun had had a sheltered adolescence, but how, at his age, could he still not have grasped the workings of the world in which he lived?

A year ago, Yeong-pyo had been willing to turn a blind eye to the incident of the comic skit, but for the same misdeeds to be repeated today was too much. Any action, any utterance, was observed and documented, not only in the military theater or the foothills of Mount Baekryeon, but even a thousand ri underground – was it conceivable that Kyeong-hun could be ignorant of this? Could he really be so idiotic? No. Just as the military director had written, though Kyeong-hun had clearly intended his written statement to come across as the account of a naïve, wide-eyed young man, in reality he was ‘more canny than he’s letting on’.

That louse of a son has his head on backward, and it’s those damned liberalization broadcasts that have spun it around for him – 180 degrees, until he can’t tell north from south. Would there be the slightest blemish on his record otherwise, would he even cast his eyes at this Kim Suk-i? Kim Suk-i, who everyone knows is the daughter of a political prisoner!

Recalling all the trouble he’d had extracting a promise from Kyeong-hun to break off the relationship – like getting blood out of a stone – Yeong-pyo swore under his breath and dashed the rainwater off his chin. To his surprise, he found himself already home; he’d been too preoccupied to notice his surroundings.

‘Is Kyeong-hun here?’ he snapped, only halfway across the threshold.

‘Not yet, and with this rain . . .’ Unable to gauge her husband’s mood, Kim Sun-shil had no way of knowing her words would only provoke him further. ‘I’m getting quite worried, you know.’

‘Hah! Don’t waste your time.’

‘What? How can I not worry? Only today, two people from the food factory were killed in a landslide while picking flowers in the mountains, and the little boy who got bitten by a snake yesterday died this morning.’

‘Yes, yes, all right.’

Nothing irritated Yeong-pyo so much as having to listen to someone tell him what he already knew. Though it was less than a week since the official mourning period for Kim Il-sung had begun, anything that passed for a flower bed had already been stripped bare. It was impossible to find even a single bloom in the small gardens attached to residential blocks, let alone in the public streets and parks.

Though this hadn’t been made public, a day or two into the mourning period people had cottoned on to the fact that their visits to lay flowers at one of the newly erected altars were being secretly tallied. Not only had one such visit per day become a hard-and-fast law, but there were even people who went once before each mealtime, morning, noon, and night. There were hundreds of altars all across the city, in local Party offices, factories, even schools, and what with each of the five-hundred-thousand-odd inhabitants requiring a steady supply of flowers to take there, there was nothing for it but to send workers and pupils out of the city to gather wildflowers. In Yeong-pyo’s unit, the daily task of picking enough flowers for each member to lay a bouquet at the altar was delegated on rotation.

Children and adults alike roamed the mountains, and with the monsoon season making the ground treacherous, frequent accidents were only to be expected. Yeong-pyo’s wife’s anxiety was far from baseless. But this wasn’t enough to smooth the edges of his temper.

‘If that damned louse dies in the mountains, good riddance!’

‘What?’

‘Look at this.’ Yeong-pyo tugged the bottle out of the pocket of his sodden trousers and threw it onto the floor.

‘What’s that?’

‘What does it look like? Alcohol!’ Yeong-pyo took himself off into the next room, sliding the door roughly closed behind him.

Kim Sun-shil narrowed her eyes in annoyance, frustrated by the conversation’s having been cut short before it had properly got going. That husband of hers, so conservative and uptight that even today, after their more than three decades as man and wife, he would only ever get changed behind closed doors!

‘Well, what about it?’ she called through, her curiosity tinged with alarm. ‘What’s it got to do with us?’

‘Don’t you know a piece of evidence when you see it? Evidence of debauchery, lasciviousness, self-indulgence . . .’ Yeong-pyo interrupted himself with a groan; he was clearly having difficulty removing his wet clothes. ‘He was supposed to be picking flowers, but it was a different young bud he was after.’

‘Kyeong-hun, you mean? And who was the “young bud”?’

‘Kim Suk-i.’

‘What?!’ Sun-shil swept the door open, causing her husband to hastily yank his trousers up. He needn’t have bothered; his wife’s vision was entirely filled by the faces of the two Suk-is, who were known at the factory as Big and Little. ‘Which Kim Suk-i? That Big Suk-i again?’

‘Would I be here now if I was sure of that? I would have gone to hunt down that louse of a son and put a bullet in his head!’ Yeong-pyo gripped the belt of his trousers near the holster and shook it so violently he threatened to do himself an injury. His matchstick waist sticking out above the belt looked narrow enough to have fitted down a single trouser leg. ‘In fact, we’ve had a stroke of luck. Whoever the agents were, they were too dim-witted to do a thorough job of it. Their report didn’t clarify which Suk-i it was.’

‘It must have been that Big Suk-i. He must have started up with her again.’

‘What makes you so sure?’

‘I’m guessing, of course. I know you did everything to separate them.’

Biting her fingernails in a nervous reflex, Sun-shil let her gaze stray to the sunflower outside the window.

Somehow those resplendent petals had managed to keep their shape even while being battered by the rains, and perhaps it had something to do with this impressive appearance, as well as the plant’s towering height, that led them to be overlaid in Sun-shil’s mind’s eye with a dazzling face. It belonged, of course, to her son Kyeong-hun, a strapping lad whose wavy hair undulated like grass in the wind. His broad, open forehead gave him an air of intelligence, while his slightly upturned eyes denoted keen perception. In other words, he had a face that seemed well suited to being buried in a book, as Kyeong-hun’s so frequently was.

At some point early on in their marriage, her husband had made what she’d assumed at the time was a joke, though this was out of keeping with his serious, somewhat po-faced character: I’ve always been regarded as a stickler, my heart as gnarled and knotty as an old tree, and I’m determined not to pass such qualities on to my offspring. That’s why I made such heroic efforts to win your hand – I wanted your height, your fine features, your artistic talent. And so, if I’m to see my wish come true, you must bear me a son who takes after you . . .

And Yeong-pyo’s wish had indeed come true, though in this case he would have been wise to heed the old adage ‘Be careful what you wish for’. After all the effort he’d made to rid himself of those ugly traits, he now had his own son to thank for a whole new set of pains. When it came to personal conduct and an understanding of the ways of the world, Kyeong-hun would be found sorely lacking if measured against his father.

It hadn’t been that long ago that Yeong-pyo had forced Kyeong-hun to promise to break off with Big Suk-i. Sun-shil had been giving the house its evening tidying when she noticed something out of place – an official document lying casually unfolded between the neat stacks of filed papers on her husband’s desk. No sooner had she scanned the heading, ‘Order for the Deportation of the Family of Kim Sung-bin’, than her puzzled frown transformed into a look of horror. Wide-eyed, she skimmed down to read that, for various reasons, the wife and children of Kim Sung-bin were to join him in a labor camp for political prisoners. There was only one Kim Sung-bin she knew of to whom such an order might apply – Big Suk-i’s father. Sun-shil swiftly tucked the paper into her jacket pocket, glancing around nervously as though she might have been being watched. She hurried off in search of her husband, and thrust the document in front of him with a trembling hand.

‘Even monkeys occasionally fall from trees, they say, but how could you be so careless? To bring such a thing into our house, and then to leave it lying around for anyone to see!’

‘There are times the monkey falls, but there are also times it only pretends to.’

‘But is it true? Is the family going to be deported?’

‘Damn it, what did I just say about pretending? Put that back where you found it!’

Only then did Sun-shil realize that this was all a ruse of her husband’s, deliberately designed to gauge the level of Kyeong-hun’s affection for Kim Suk-i – and ideally to disperse it.

Sure enough, Kyeong-hun rose to the bait. A few days later, the three of them had settled down in front of the TV for an after-dinner film, Outpost Line. Not long in, Kyeonghun was heard to mutter something, apparently in response to the action on-screen. His words were muffled, as though spoken to himself, but Yeong-pyo’s sharp ears pricked up.

‘It’s the same now as it was back then – class enemies are still cut from the same cloth.’

‘So you do have some sense, after all!’ Yeong-pyo exclaimed.

‘Haha, father, do you really think I’m such a lost cause? It’s just that, you know, I tend to apply our Party’s policy of ‘benevolence and tolerance’ when I look at others.’

‘Such a policy is all well and good, but it can’t just be applied indiscriminately; leniency is intended only for those who merit it.’ Yeong-pyo’s reproof was mild, his tone sympathetic; such a harmonious conversation between father and son was almost unprecedented.

‘Indeed,’ Kyeong-hun responded, ‘and if the Bowibu is to be as effective as possible I think you have to be ruthless in determining who merits the opposite. A bad apple rots the barrel, isn’t that what they say? It’s not enough to crack down on a single individual; the entire family ought to be purged. Families, for example, like – well, it’s a little awkward for me to say this, given the relationship I was recently involved in, but like that of Big Kim Suk-i.’

‘Now, now,’ Yeong-pyo blustered, ‘whatever are you –’

‘Don’t you think I have eyes in my head, Father?’

‘Ach, how could I have been so careless? That document I left on my desk . . .’

In this way, the two men’s verbal fencing seemed to have ended with the elder on top. As far as Yeong-pyo could see, Kyeong-hun had as much as renounced any connection with Big Suk-i. Only Sun-shil was unconvinced by this apparent triumph. Her husband might have prided himself on his cunning in catching a slippery fish, but to her the fish seemed strangely eager to take the bait, even casting itself up onto dry land without waiting to be reeled in.

Now, judging by recent developments, it was clear that Yeong-pyo had been the one taken in that day – hook, line, and sinker. No matter how much Sun-shil wanted to believe otherwise, there wasn’t a scrap of evidence that might suggest it was the other Suk-i that Kyeong-hun had gotten mixed up with. Why, the pair had never been known to exchange even a casual remark! And yet, even while perfectly aware of this, Sun-shil and Yeong-pyo could not quite bring themselves to relinquish the possibility that it was indeed Little Suk-i. But they knew they were deluding themselves. If nothing else, Kyeong-hun simply wasn’t the type to cast a young woman aside like a bit of old rubbish because his parents were opposed to the match.

Sun-shil’s chest felt suddenly tight. This time, the scene that swam hazily into her head was that of her husband and Kyeong-hun’s eventual clash, which had genuinely threatened to end in a gunshot.

‘Hand me my umbrella!’ Sun-shil started at this barked command, jerked abruptly back to the present. She turned away from the window and moved to pass her husband his umbrella.

‘Where are you off to now?’

‘The factory altar,’ Yeong-pyo snapped over his shoulder, already halfway out of the door. ‘The nation is in mourning, even if it that crazy bastard has forgotten it!’

Sun-shil had just finished preparing dinner when Kyeong-hun arrived home, his sopping clothes and squelching shoes making him look as though he’d been put through a wringer. He’d had to stop by each household affiliated with his factory, to distribute that day’s allocation of flowers. Yeong-pyo arrived home not long afterward, having had his own rounds to make – checking in on his agents, who were stationed at every local altar.

‘Dinner’s ready!’ Sun-shil seemed anxious to get the meal out of the way before a squall blew up, but Yeong-pyo had no time for such niceties. He looked over at Kyeonghun, who, after changing out of his wet clothes and running a comb through his hair, had promptly installed himself on one of the floor’s warm spots and buried his nose in a book. The boy was the picture of innocence, which only served to boil Yeong-pyo’s already hot blood.

‘Close that book.’ Yeong-pyo’s voice was cold as ice. Kyeong-hun glanced up, tilting his head to one side and widening his eyes in an affectation of puzzled surprise. ‘You ought to show more care when you go to pick flowers.’

‘Oh, but I am careful. What with this recent spate of accidents –’

‘Acting, again!’

‘Why, Father, whatever do you mean?’

‘I had to stand in the meeting room today and have my name dragged through the mud. And not just my name – my whole political career!’

‘Really? But surely not because of me?’

‘Oh, “surely not”, is it? You worthless brat! You swan around plying yourself with alcohol in this time of national mourning, and have the gall to play the innocent!’

‘There must be some misunderstanding; could you be a little clearer?’

‘Clearer!’ Yeong-pyo whipped the plastic bottle out from underneath the table and slammed it against the table with such force it might have been driven into the wood if it had been made of a harder material. ‘This seems clear enough! What do you have to say for yourself?’

‘I’m afraid I can’t think of much. It looks like a perfectly ordinary bottle to me.’

‘So perfectly ordinary that you don’t remember drinking out of it? And how about the girl you were drinking with? I suppose you don’t remember her either? The same Kim Suk-i whose family you denounced in this very room? Have I jogged your memory yet?’

‘I see. So you heard this from the Bowibu director?’

‘You admit it, then!’

‘That’s right, it’s all coming back to me now. This bottle . . . and the rest . . .’ Kyeong-hun gulped, and the sound of his dry throat convulsing made his mother flinch.

‘Kyeong-hun!’ Sun-shil broke in, hoping to defuse the situation while there was still time. ‘If you were any other worker who’d stepped out of line, your father would simply punish you and have done with it. You know that, don’t you? It’s for your own good that he’s trying to make you see reason. Isn’t it time you put your shameful discharge from the army behind you and started making something of your life?’

‘I understand, Mother, honestly I do. But can’t a man hold his female comrade’s hand when they’re walking along the edge of a cliff? A comrade whom he works with every day?’

‘It was Big Suk-i, then?’ Yeong-pyo’s lip curled in disgust.

‘Yes.’

‘So it was all an act, that spiel you came out with while we were watching Outpost Line?’ Yeong-pyo ground the words out from between clenched teeth.

‘I’m sorry. That was . . . Forgive me. But I wasn’t the only one acting, was I, Father? You were the one who began it, pretending to have accidentally left a classified document lying around in plain view. You, who’ve never made the slightest misstep in your whole career! How was I supposed to respond? I went along with the performance only because I wanted to reassure you, both of you. I didn’t want you worrying about Big Suk-i.’

‘What is there between you two?’

‘Well, I can’t see myself marrying her, so you can rest easy on that count. But I can’t just cast her aside, either. She’s someone for whom I feel a deep affection – proper comradely affection, you understand, all aboveboard – and a great deal of sympathy, too. She has so many talents, yet she’ll never be given the chance to shine. And after all, what was her father’s great crime? Only to say that Kim Jong-il had taken a second wife, which everyone knows is true.’

‘Quiet!’ The plastic bottle flew through the air and struck Kyeong-hun’s cheek. ‘You’re a dyed-in-the-wool reactionary! No wonder you get drunk when you should be shedding tears.’

For Kyeong-hun, this appeared to be the final straw. His hand had flown up to his stinging cheek; now it trembled as he held it there, almost imperceptibly mirroring his twitching lips, which he pressed even more firmly together as though battling to hold his emotions inside. Suffering under an equal strain, Sun-shil held her breath and wrung her hands as her gaze flicked nervously between the two men.

After a brief while, Kyeong-hun recovered himself sufficiently to be able to open his mouth and speak in a relatively measured tone, though one which hummed with an undercurrent of agitation.

‘Father, this is too much! I might not be winning any medals for loyalty, but I know the proper conduct for mourning the deceased. Have you ever heard of someone drinking meths?’

‘What?’

‘Soaking your clothes in methyl spirits is proven to ward off snakes; that’s what was in that bottle I had with me. If you don’t believe me, you can call Mr. Park at the lab right now. He’s the one I borrowed it from.’

‘Kyeong-hun!’ Choking out her son’s name, Sun-shil pressed his hands between her own. Tears spilled like a shower of rain from her eyes, still bright despite the lines of age.

Witnessing his mother’s distress caused Kyeong-hun’s eyes to tear up in response. All that his ‘twenty-six years of drama school’ had taught him to bury deep inside him now refused to be suppressed any longer

‘Don’t you see how miserable it all is? How wretched? People who are so eager to catch others out, they’ll even scrabble around after rubbish like this.’ He gestured angrily toward the bottle at his feet. ‘A sincere, genuine life is possible only for those who have freedom. Where emotions are suppressed and actions monitored, acting only becomes ubiquitous, and so convincing that we even trick ourselves. Look at all these people, sobbing over a death that happened three months ago, starving because they haven’t been able to draw their rations all the while. What about the mother of the child bitten by a snake while he was out gathering flowers for Kim Il-sung’s altar? Perhaps she finds her private grief useful for shedding public tears. Isn’t it frightening, this society which teaches us all to be great actors, able to turn on the waterworks at the drop of a hat?’

‘Shut up, you little idiot! Enough of this reactionary nonsense!’

‘But those who see forced tears as a sign of loyalty, of solidarity? Aren’t they the real idiots? Surely you know that whatever the play, the curtain always falls in the end.’

A strangled cry emerged from Yeong-pyo’s throat as he flew out of his chair, fumbling at his waist as though in the grip of some violent compulsion.

‘What are you doing?’ Sun-shil rushed to place herself between husband and son, staring at the former with a look of horror.

‘Out of my way!’ With one hand, Yeong-pyo thrust his wife aside, while in the other, the metallic gleam of the gun’s muzzle announced its venomous bite.

‘Go ahead, shoot,’ Kyeong-hun said, standing up and spreading his arms to bare his chest. ‘Kill me, if that’s truly what you want! But even if you fill this body with bullets, you’ll never kill my wish to live a life fit for a human being!’

A gunshot rang out in reply, and the room was abruptly plunged into darkness. There was a brief shocked silence, broken then by Sun-shil’s keening as she crawled on her knees to where she guessed her son had been standing. Flailing madly, she bumped her shoulder against the table, and something clattered noisily to the floor. The echoes had barely died down when the telephone’s harsh ring made her jump, the sound seeming strangely incongruous.

‘Is it a blackout? The garage . . . Get to the garage! Send cars out to the altars and light them up! Hurry!’

Sun-shil couldn’t tell whether these words were coming from this world or the next. But then she felt a hand clutch hers.

‘Mother!’ Here he was, her son, bawling like a baby as she felt up his arm to check his shoulder, his head. There was the sound of the front door being flung open and footsteps racing out. The night was pitch-black, the sky free of even a single point of light. Though the rain had finally let up, the wind was howling with renewed vigor. The sound of a hundred whips slamming into the air filled the space between heaven and earth.

Yeong-pyo raced headlong down the stairs and out to the factory’s main gate, where an altar had been set up beneath a large oil painting of Kim Il-sung, adorned with the inscription ‘We will worship the Great Leader until the sun and moon go out.’ It had been installed by the gate, as the company common room was far too small to accommodate the thousands of employees who made a daily pilgrimage of mourning. The cars that had been driven out – on Yeong-pyo’s directive – were already parked in a semicircle, arranged so that the beams from their headlights were best placed to illuminate the altar. There were five of them, lighting up the marble plinth so brightly that each petal on each bouquet could be clearly picked out. A drawn-out chorus of wailing was audible even in spite of the wind’s almighty din.

A fixed complement of mourners was guaranteed at any one time; when one left he or she would be instantly replaced, just as the water level is regulated in an artificial lake. Seeing the ebb and flow around the altar operating just as it should, Yeong-pyo ought to have felt sufficiently at ease to go and sit in one of the cars and get out of the wind. But there was no way he could sit easy at a time like this.

He needed to get a good look at the current crop of mourners. Was it true that they were merely actors, crying fabricated tears? Kyeong-hun’s words still rang shrill in his ears, whipping up a storm of confusion. He pulled the brim of his hat low over his eyes and slipped into the wailing throng. Almost immediately his gaze landed on the mother of Big Kim Suk-i, a painful shock to his already frayed nerves. That she, of all people, would be standing right in front of the altar . . . What kind of trickery was this?

When he’d had the impulse to conceal himself among the crowd, to assess the sincerity of their grief, wasn’t this woman from Haeju precisely whom he’d had in mind, her husband languishing in a political prisoners’ camp, always complaining that her family was on the brink of starvation? Now, faced with the sight of the real-life woman laying her bouquet on the altar with a heart-rending cry of ‘Great Leader, Father!’ Yeong-pyo trembled. The tears were streaming down her cheeks! It was shocking, appalling, something that Yeongpyo would never have considered possible even if he’d read it in one of his agent’s reports. He felt as though he had stumbled into the presence of a nine-tailed fox, a cunning, treacherous creature who must be avoided at all costs.

Turning and stumbling back, Yeong-pyo was in too much haste to extricate himself from the crowd of mourners to worry about drawing attention to himself. Pain was radiating from his liver, yet he could not have been said to feel it. A shrill whine throbbed in both his ears, as though a flock of cicadas was trapped inside his skull. What he had just witnessed felt as unreal as a dream. Such tears were not to be believed.

If even someone like Big Suk-i’s mother was able to sob convincingly, to cry out ‘Great Leader!’ in a suitably mournful tone . . . But how were they managing to squeeze out actual tears? Did they carry bottles of water concealed about their person, to splash on their faces when no one was looking?

It’s called stage truth.

Who said that? The voice had sounded like Kyeong-hun’s, but also like that of an old army comrade of his . . .

Stage truth . . . As Yeong-pyo dragged himself over to a corner, his feet seemed to move of their own accord, while his mind, unmoored, drifted further from the here and now. That’s right. Anyone who has that can produce a few tears, even Big Suk-i’s mother. But it usually takes an experienced actor to really pull it off . . .

After all this time, have you still not figured out that that’s exactly what she is? That voice again – who was it? Could it be that Kang Gil-nam, who had insisted on performing the second improvisation? A woman like her, with forty-five years of acting school under her belt, forty-five years in which to master the only scenarios she’ll ever need: ‘It Hurts, Haha’; ‘It Tickles, Boohoo’. And no wonder she’s excelled, with you to train her up. Strict teachers are always the most effective.

Forty-five years? But she can’t be older than forty-five now. And I’m the one who trained her, who taught her the cunning of a nine-tailed fox? Me?

Yes, you, Father. You’ve had fifty-eight years of the same training, after all, and you’ve always been top of your class.

Kyeong-hun, you bastard! I ought to have put a bullet in you just now. I don’t know where you got it from, this insolence, this insubordination . . . but it has nothing to do with me. Nothing, do you hear me?

You’re too modest, father. You gave a display of your talent only this morning; how to produce a pitcher’s worth of tears from a cup of sadness.

What are you talking about, ‘this morning’?

In front of the Bowibu director. And it came in handy, didn’t it?

What? I, I don’t know what you’re talking about. I don’t know. I don’t . . .

Yeong-pyo caught his foot on something, stumbled, and fell. Groaning, he struggled to his feet, but seemed to have left his disordered mind scattered over the ground. He stood, his features blank and uncomprehending. The gusting wind tugged at his clothes.

‘Eoi, eoi!’

That sound, threaded through the howl of the wind like the keening cry of some water sprite, making the hairs stand up on the back of his neck – could such a mournful wail really have come from Big Suk-i’s mother? Was it possible?

Yeong-pyo trembled all over. He had blundered over to the small park, off to one side of the deserted factory buildings. But his immediate surroundings had passed beyond his comprehension. The altar’s brilliant halo filled a vacant gaze, in which the pupils had come unmoored. The intersecting beams from the cars’ headlights resembled theater spotlights. One beam stretched all the way to where Yeong-pyo was standing, illuminating the somber pines and low stone benches.

‘These pines are wonderfully drawn – just like the real thing! Wait a minute, whose scene is this? Ah, that’s right, that’s right . . . ’

Passing between the trees, a trainer took the stage. A trainer bearing the indelible stain of a horrifying crime, who must now press the barrel of a gun to his temple and bring this whole matter to a close.

The bang of the gun ripped through the warm night air, but Yeong-pyo was beyond hearing it. Hong Yeong-pyo, a stern director who had demanded the same stage truth no less from himself than from others, had chosen to bring the curtain down, in advance of that of his fellow actors.

29th January, 1995

*

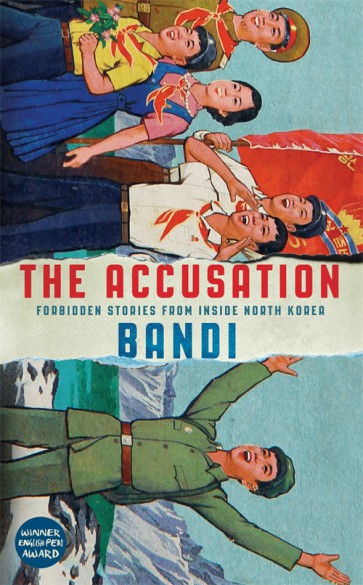

A note from the publisher: The Accusation is, to our knowledge, the first book of fiction to emerge that was actually written by someone living within the North Korean regime. This is a collection of stories written between 1989 and 1995 by Bandi, a pseudonym for the author whose real identity cannot be revealed. We know that Bandi is from the north east of North Korea, that he is part of the regime’s official writers league, and that his gradual disillusionment at the regime led him to secretly document daily life as he saw it around him. We know that he kept these writings hidden for many years, until recently one of his relatives defected to South Korea, and was able to arrange for the manuscript to be smuggled out. The UK edition of The Accusation was granted a PEN Translation award from English PEN at the end of 2016.

The Accusation will be published by Serpent’s Tail in the UK and Grove Atlantic in the US.

Photograph © Sheridans of Asia