The river is deserted. It’s a dead river, and it’s rare to find anyone fishing on it. Some use small, rudimentary boats to cross it on a calm day, and others take a chance on contaminated fish still flopping about. A fish’s eyes, even after it’s dead, gleam, reflecting the sunlight. A ruminant’s eyes are black as night. Inside them is only darkness, and it cannot be trespassed. Perpetually unfathomable.

It’s called Rio das Moscas, and ever since slaughterhouses began to spring up around the region known as Ruminant Valley, its clean waters have brimmed with blood. All kinds of things, organic and inorganic, lie at the bottom. Human and animal.

The wind shakes the tree branches and makes the grass lie back on itself, creates ripples on the surface of the river, its waters enveloped in hollow silence between the mountains, which lends a feeling of eternity to the valley’s landscape.

The sun is covered by a thin layer of clouds; the sultry heat creates a slight fug, blunted by the occasional gust of wind. Edgar Wilson looks around and up, studying the walls that surround him. The wind blows through the gaps, making its sinuous way into the valley.

He takes a deep breath. He breathes in more than air, he breathes in the wind that travels everywhere, the wind that has the privilege of belonging everywhere. It is impossible to know its path, to pursue it or to catch up with it.

Edgar checks the time on his watch. It’s still very early. He gets up from the tree trunk where he’s been sitting and returns to the pickup truck. He’d stopped there for a few minutes, to feel and breathe in the wind blowing alongside him. Once again, he’d been asked to take an invoice to the hamburger plant, first thing in the morning, before his shift.

Skirting along the banks of the river, its turbid waters reflecting the early morning sun, Edgar Wilson drives at a relaxed pace. As he passes through the gate to the slaughterhouse parking lot, he notices that the wooden sign with the place’s name is loose on one side. He thinks about returning later to straighten it. It says Touro do Milo Slaughterhouse, with a drawing of a brown bull’s face. But they slaughter everything there: steer, heifers, sheep, hogs, rabbits, buffaloes and bulls. They take anything. As long as someone else pays for it.

Edgar Wilson gives a quick knock on the half-open door to his boss’s office. Milo grumbles for him to enter. Without saying a word, Edgar hands him a document, but he doesn’t know much about it.

‘Edgar, we’ve got a shipment arriving soon, from far away. They’re Lebanese cows. They’ve travelled for almost a month, and they’ll be in bad shape when they get here.’

Milo pauses, checking the document he’s just received from Edgar, who, in turn, wonders what Lebanese cows look like and if they require any different handling.

‘The good news is Santiago has arrived and starts working with you today. He’ll be in the next box over. We’re going to streamline the work.’ As he says this, Milo raises his hands to the sky. Streamlining must be something like divine Providence, thinks Edgar Wilson.

‘Can I count on you, Edgar?’

‘At your service, sir.’

Milo slaps the table. Now he’s visibly excited about the Lebanese cows and the reindeer slaughterer.

‘One more thing. . . it’s about Zeca. I think you do know where he is.’

Edgar Wilson doesn’t give the runaround or deny things. He doesn’t lie and he’s never known how to. At Mass, he was always told that lying is a thing of the devil.

‘I do know, sir.’

Milo waits for the rest of his answer, but Edgar says nothing. Milo asks the question again:

‘So, where is he?’

‘In the river.’

Milo sits in suspicious silence. He lowers his head slightly and looks at his hands, clasped on top of the desk.

‘Rio das Moscas?’

‘Yes sir.’

‘And how’d he wind up there, Edgar Wilson?’ asks Milo with an inquisitive look after raising his head and wiping his face with a washcloth.

‘Put him there myself. I put him down, then threw him in the river.’

‘Why did you do that, Edgar?’

‘He mistreated the cattle. He was no good.’

‘That’s a crime, Edgar. You killed a man.’

‘No, Senhor Milo. I’ve killed more than one. Just the men who were no good.’

Milo decides to keep quiet. He knows Edgar Wilson’s loyalty, knows his methods, and he knows that Zeca really was useless. No one had reported him missing, and if anybody came looking for the boy, he would simply say that he never showed up for work again. That he doesn’t know where he’s gone off to. Just as no one questions the death in the slaughterhouse, certainly the death of Zeca, whose rational faculties were on par with the ruminants, would remain ignored. Senhor Milo knows cattlemen, he’s cut from the same cloth. No one goes unpunished. They’re men of cattle and blood.

The old truck rattles in the distance, moving at no more than fifty kilometres an hour. The ruts in the road are deep in some parts and cause the trailer to careen from side to side. The clouds covering the sun have dissipated. The brightness in the sky ensures that every man in the slaughterhouse is chased by his shadow, a shadow darker than most of the workers there. The truck bed is strapped to the cab with frayed rope, the tyres are bald, and the rusty bumper gives the vehicle a decrepit appearance. The men tumble out of the bed, the older and heavier ones brace themselves against the gate before hitting the ground. A bottle of cachaça has already been consumed during the trip. The smell of booze mixes with bad breath and the odour of the entrails that occasionally fall to the ground and are never completely cleared away.

Each man goes to his post under the watchful eye of the slaughterhouse foreman, Bronco Gil. Tall, with straight hair and tanned skin, and exceptionally strong, he always wears braces and leather boots, even in the heat. He is a self-proclaimed hunter. When a cow breaks free and escapes, he’s able to capture it quickly. When a jaguar or wild boar threatens the cattle’s safety, he’ll sit for days and nights on end in the woods, waiting to ambush it. If a disagreement between the employees oversteps the limits of peaceful coexistence, he knows how to deal with it. Bronco Gil is a mediator, a hunter, a butcher and one of the vilest individuals Edgar Wilson has ever met.

Despite his ability to handle a shotgun, he prefers a bow and arrow. He is the son of an Indigenous woman and a white rancher. Until the age of twelve, he lived with a tribe where outsiders were not allowed, and cut off from the world, he lived immersed in a culture with little fondness for affection. He accidentally lost one of his testicles in an initiation ritual into adulthood. This made him quieter but more aggressive. Some time later, his father decided to go fetch him and take him to live on the ranch, as he needed a helper. In exchange for some tins of potted meat and lard, Bronco Gil was whisked away to a region far removed from the tribe. His father, by then an old man and a widower, had lost his three other sons, who’d spent weeks hunting down two jaguars that had been circling the ranch’s cattle. Overnight, the old man found himself alone and with no heirs, so he decided to rescue Bronco Gil and try to civilise him before it was too late. That’s the way the old man thought. But instead civilisation barbarised him, and what little affection he’d known became like the dust on the ground he walked upon. Civilised, wearing boots and braces, and combing his hair back with Mutamba and Juá hair tonic, he was taught to hunt for pleasure and to never turn his back on anyone. They lived together, father and son, for ten years, until the old man died of a heart attack while riding among the cornfields.

On his own, Bronco Gil lost the farm, the horses and two pickup trucks at card tables. The rest of what he had was spent on hookers and booze. Late one night, walking home drunk, propped up by two women, they were run over and left for dead. The deserted stretch of road prevented help from arriving for eight hours. The women didn’t make it; he was rescued in time. But his left eye didn’t stand a chance. A vulture ate it while his right eye watched. In its place was now one made of glass; brown, like the real one, but that pops loose from its socket now and again.

Bronco Gil rolls a cigarette and tucks it behind his ear. He’ll probably light it at lunchtime. He picks up a clipboard and with a black pen takes attendance. He knows each one by name and nickname. Zeca’s name is still on the page, but he hasn’t been marked for several days.

The delivery of Lebanese cows is already running late. Edgar Wilson greets Bronco Gil as he walks past and heads to the locker room, where he will get ready for work. He puts on bloodstained jeans and a threadbare beige T-shirt, black rubber boots and a white jacket. On his head, a faded cap with blood spatters.

In the stun box, he finds Santiago leaning against the wall, waiting for him. He’s not very tall, but he’s strong. He has a few tattoos on his arms and neck, and his long hair is tied back with a rubber band.

‘You must be Edgar Wilson,’ says Santiago, reaching out to shake his hand.

Edgar accepts the handshake. Santiago is a restless, anxious type. He darts around and picks his nose constantly.

‘I used to slaughter reindeer in Finland.’

‘You got any experience with cattle?’

‘Yeah, I used to slaughter cattle on a farm in the Irish countryside, until I ended up in Finland with the reindeer.’

Santiago smiles the entire time he talks, a nervous grin. That kind of agitation won’t do the cattle any good, thinks Edgar Wilson.

‘Over there,’ continues Santiago, ‘we had to chase down the reindeer. They’re trapped inside a pen, and you’ve got to be real quick, quick as hell, and grab one by the neck, by the leg.’ As he speaks, he moves his hands around, hops up and down, twirls from side to side. ‘And they have big ol’ horns, like this. . . they’re sawed off to make them shorter, but they’ll still go right through you if you’re not careful, you’ve got to always be on your toes. They’re very fast animals.’ The boy’s voice is shrill and racing. Edgar Wilson digests the conversation with curiosity. ‘And I’m a very fast guy. You grab them and then, boom, you just slit its throat. It’s all so fast. Once I see the blood sinking deep into the snow. . . then I can relax.’

Edgar Wilson is transfixed. His gaze is frozen on the boy. He tries to picture the white snow; he’d never met anybody who’d seen snow. He thinks about blood against the whiteness of the ice. For the first time, he wanted to see snow.

‘Here you just need to strike the steer’s forehead with a mallet. That’s all. And you must be quick. There’s no room for error, otherwise the animal suffers.’

Santiago starts hopping from side to side as if warming up to enter a wrestling ring. He stretches his arms out behind him and to the sides. He spreads his legs apart and move his hips. As Edgar Wilson gives him instructions, he starts getting dressed: a white jumpsuit with a huge zipper down the back, rubber gloves, a rubber cap and ski goggles.

When Edgar completes his instructions, Santiago turns around and asks him to zip up the huge zipper that extends from his buttocks to the nape of his neck. Edgar zips it with one strong tug. Santiago adjusts his ski goggles, securing the elastic band behind his head, and emphatically declares he’s ready.

Edgar Wilson realises that those goggles are very effective. It’s just what he needs to keep the blood out of his eyes.

‘Where might I get some of those?’ asks Edgar, pointing to the goggles.

‘I brought them back from Finland. I used them for skiing. They’re ski goggles.’

Edgar Wilson knows he’ll never find ski goggles in a place like this, since there’s nothing but dirt, dust and mud. Santiago praises the practicality of the goggles as part of his work uniform.

‘I can try to get you a pair.’

‘How’s that?’

‘I’ve got a friend who used to fix sledges in Finland, and he came back the same day as me. He opened up a machine shop with his brothers. It’s far away, but I know he had a whole bunch of these goggles. I left some of my things with him, and he’s gonna send me everything as soon as he can.’

‘You reckon he’d sell me a pair?’

‘I’ll talk to him, and I’ll let you know.’

Edgar Wilson nods in appreciation and goes to the corner of the box, returning with two mallets. One, with a white line on the wooden handle, has his name written on it in blue ink. The other he hands to Santiago, saying ‘Follow me’. Edgar positions himself in the box and signals to let the first steer in. The animal is led down a short, narrow chute that leads to the stun box. The more skittish ones get shocked with a stick to make them walk. A window opens and the animal, crammed inside the narrow space, cannot turn around or retreat. Edgar Wilson makes a shushing sound and touches the steer’s forehead. It grows less agitated, and its eyes, less terrified. But the smell of the blood of other ruminants killed in that same place, the smell of death that emanates from Edgar Wilson and his eyes, so full of complacency, tell the animal it will die. Edgar Wilson dips his right thumb into the pot of lime and makes the sign of the cross on the steer’s forehead, raises the mallet and strikes the centre of the cross. One, single, bone-cracking blow, and the animal is out cold on the ground. Immediately, the side wall of the chute is raised, and the steer is pulled out by another employee, who will take it to the bleeding room.

After watching the procedure for a few minutes, Santiago starts work in the neighbouring box, and the pace of productivity on the never-ending line of ruminants to be slaughtered picks up, though it never seems to get any shorter. Edgar Wilson thinks about hamburgers as he works, as he swats away flies and wipes the blood spatter from his face. At the hamburger plant, all that white reflects a peace that doesn’t exist, a blinding glare that obscures death. They’re all killers, each their own kind, performing their role in the slaughter line.

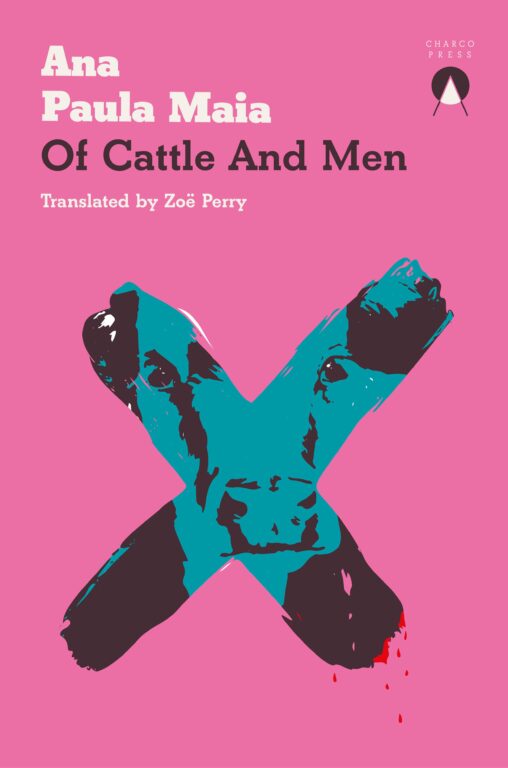

Image © Ars Electronica