WHAT A GOAL! goal of the season, Justin Fashanu we want you, we love you, the way you volleyed it in with your left foot from well outside the box, the way you spun round and slipped it between the goalkeeper’s hand and the right post, the fans wanted you, Norwich City FC did, your teammates jumped you like only footballers playing on the exact same team jump each other when one of them scores. Justin Fashanu, we wanted you when you became the first black British player to sign for £1 million to Nottingham Forest in 1980, we wanted you then but we didn’t want you in the late 1990s when you hanged yourself in a garage in Shoreditch, Fairchild Place, after what would have been your final visit to Chariots Roman Spa, the local gay sauna across the road, which personally I never attended and it’s not like I didn’t try or didn’t collect Chachki from Chariots on many occasions. I remember a time round 01 or 02 when I literally lived outside Chariots, in the small, fenced-off carpark by the main entrance; the entrance was flanked by fake Roman columns and plastic statues of lions, its roof a triangular awning with Old English lettering, which all felt strangely reassuring given I owned nothing but the trackies I was wearing and a fanny pack containing my passport, a kitchen knife and a can of pepper spray I found on the floor. Justin Fashanu, I admit that I wanted you, to be my stepdad, that I, aged seventeen, had come to Chariots Roman Spa if not the UK in 01 looking for you, and that I waited outside with the lions expecting you to appear from under the awning, triangular, hair still wet, refreshed and affirmed in your gayness, at any moment, I’d worked hard to forget what you did in the garage on Fairchild four years prior but really I knew, I knew that you wouldn’t appear, and that although I was still underage in 01 I was already too late by far. Justin Fashanu, your parents didn’t want you, in the mid-1960s they gave you and your younger brother to Barnardo’s foster home for vulnerable children, the charity est. 1866, count yourself lucky you got there when you did and not earlier, like the end of the nineteenth century, when Barnardo’s sent British children abroad as slaves, a widely known fact. Shortly after, a white Norfolk family adopted you and your brother, what a thing to take on, raising two black boys in an era when racism was rife in the English provinces, implying it’s less rife today which is a misconception, but it takes a strong woman, the people of Norfolk would say, expressing sympathy especially for the white mother as if it had been a tremendous burden to parent a future footballing legend like you, Justin, but Justin, know that I said what I said about your birth-parents deliberately, provocatively, knowing full well they probably did want you, didn’t want to send you Barnardo’s, your birth-father left and your birth-mother couldn’t afford you on her own, so she did what she had to and look how that turned out, for a while you did well, and I’m sorry the prejudice against birth-parents is probably mine. Life isn’t fair to parents, nor children for that matter. The one place where fairness is really writ large is in London nomenclature, take Fairfield House in NW1 or Fairchild Place in EC2A, the ‘fair’ in each case denoting a light complexion or whiteness, in other words an investment in racial privilege, in direct contravention of impartiality and equal treatment, as a matter of fact, you, Justin Fashanu, weren’t white, and you weren’t treated equally, you’d be the first to say that you were discriminated against, bullied and abused for being black your entire life, and even more so, in the context of professional football, for being gay. Nottingham Forest wanted you to the tune of a million, but they didn’t want you whoring in gay, the penalty for frequenting – to quote manager Clough – ‘poof clubs’, and for adopting a lifestyle incompatible with FIFA’s entirely unwritten rules and regulations was a lengthy period of exclusion from training at Forest, which, on top of the bullying, led you to underperform on your return to the pitch, while crashing several cars off the pitch, sustaining a knee injury before leaving Nottingham Forest for a nomadic life, Brighton & Hove, America, until 1990, when nobody, nobody, wanted you to publicly come out in the tabloid press, becoming the only prominent male player in English football ever to do so, the record still stands. The backlash was ferocious, and apart from Torquay United who’d just been promoted to Division Three and who wanted a major player for a bargain basement price, no club offered you a full-time contract ever again, the FA didn’t want you and neither did your younger brother, who disowned you publicly on multiple occasions but who has since apologised. Fast forward a few years and Justin Fashanu, we didn’t want you in March 98, we never wanted you less than when a seventeen-year-old accused you of sexual assault in the US state of Maryland where homosexual acts were illegal at the time, yet the case hinged on lack of consent, the boy testified that you, Justin Fashanu, had been performing non-consensual sex acts on him when he’d woken up, so you fled to England, expecting you wouldn’t get a fair trial in the US because you were black, and gay, you knew that America didn’t want you, but, apart from Chariots Roman Spa, neither did England. So you went Chariots in May 98, Roman sanctuary in the middle of Albion. If only you could’ve stayed in there forever, but you couldn’t, Chariots have limited opening times, linked to essential maintenance conducted during the hours of closing, rather than, say, staff availability, and that was a problem – once Chariots closed, you had nowhere to go but that Fairchild Place garage with the supporting beam and the rope. During the time I lived in the carpark I got friendly with several members of staff including one cleaner, or ‘spa assistant’ as the official job title would have it, who told me that first and foremost he was grateful for, not just wipeable floors and walls, but wipeable ceilings, and that whoever designed the interior of the spa must have anticipated the levels of disinhibition it would elicit, not just exceptionally but as a matter of course and in the majority of its punters, and that the kind of specialist cleaning involved was as life-affirming as it was stomach-turning. The job wasn’t for everyone, and certainly not, according to my friend the spa assistant, who tended to have a Tesco sandwich in his break, no fresh fruit in sight, for the faint-hearted like e.g. me, there was a tinge of transphobia in the suggestions that I, with no recourse to cis masculinity, wouldn’t be able to handle the man-blood, the man-semen and the man-faeces soiling the tiles in every direction, three-hundred-and-sixty degrees, not like he could, and I have to say he was probably right. I resisted the urge to defend my masculinity by hitting my so-called friend in the mouth and asked him instead what else was going on behind that dirty, off-white and exclusionary tarp covering Chariots’s glass front entirely, I was interested specifically in whether, lately, he’d set eyes on eighties and nineties footballing legend Justin Fashanu who I explained was the closest thing to family I had left, but my friend, so-called, said that Justin Fashanu died years ago, and I had to admit that I already knew. Justin Fashanu, who knows whether it was a coincidence that Chariots’s management had me removed from their carpark later that day, they didn’t want me, they made that clear, and cleaned me away like spunk from a wipeable ceiling. Wonder of wonders, ‘Where you off to with your fanny-pack,’ young Chachki, who’d just come out of the spa, walking the length of the triangular awning, asked me. I’d spoken to them on a number of occasions. ‘Nowhere,’ I replied, in fact I’d been standing outside the gates to the carpark for several hours by this point. Chachki, as underage as myself, decided that I needed a job, ‘Are you good at cleaning?’ ‘It depends.’ Chachki said they knew of a vacancy cleaning a telemarketing office in their neighbourhood, interested? ‘Oh I am,’ I said, I came with, and the rest was as they say a mystery.

What a goal that was, metaphorically speaking, the goal of the season: I didn’t just take the job as a cleaner in the small 1960s office block corner Albert Street and Delancey, I also rented the shell of a top-floor flat that came with it, and started having a life, developing a big British heart and, soon, with Chachki, Cataclysmic Foibles. Everything meant something then. Take Cataclysmic Foibles, the name, which referred to a state of precarity in which any foible, character flaw, or momentary slip up can and will have cataclysmic personal consequences, imagine, e.g., that all you did was walk down Delancey Street, white football shirt wrapped round your waist like a skirt, red velvet bullfighter jacket on, and black montera, traditional bullfighter hat, that you had yellow football socks on, black leather loafers, and that’s all it took for everything to go wrong. That’s what years ago we somewhat childishly, imprecisely – liberally, even – called a cataclysmic foible, the fact that you wore that stuff, the skirt in particular, the fact that it was never actually about your clothes but always about you, and that if you hadn’t worn this or that skirt, or those socks, you would’ve had the exact same thing coming, the kind of thing, Justin Fashanu, that doesn’t happen to everybody, but that happened to us, Justin, and to you, a lot, that’s why we developed a language around it, we were kids, didn’t care for the precise or even correct use of words, we still don’t, we care for their capacity to give life, and to take it away. As well as being integral to the Pastel Dragons design concept, the foam-rubber spikes on Chachki’s beige puffer vest in case you were wondering constitute an example of what years ago we described as a foible, something that catches, that you may get caught up in, the bent dragon’s tail with the feather as its tip doing similar symbolic work, see? Talking of symbolism, Justin Fashanu, Cataclysmic Foibles 18, was it, or 19, we’d just started to step up production values, introduced a large, cone-shaped spaceship made of papier-mâché hanging from the ceiling, slap-bang in the middle of my flat, and the idea was for the audience to smash it with badminton rackets and baseball bats like a Mexican piñata, and for special treats to rain down, and they did! they did! Who knows what treats they were anymore, fortune teller miracle fishes predicting the future, or Chariots Roman Spa branded matchbooks, a gift from our sponsors, the latter, it was, with Old English lettering, blue on white, and a tiny Roman chariot on each cover. In many ways, Cataclysmic Foibles equipped us for what was to come, and I don’t just mean the learnt suspicion towards cone-shaped objects, but the fact that the spaceship piñata in the otherwise forgettable narrative Chachki and I had constructed in No. 19 came to symbolise a moment that was so incongruous and out of context with whatever appeared to be going on superficially, it offered a glimpse of a hidden reality, was very instructive, it taught us to trust the feeling we had that we were non-consensual participants in a reality put together by politicians, despots, more or less openly authoritarian leaders. Imagine living in a novel by Saddam Hussein. Did you know the former Iraqi president wrote, not just history, but at least four novels, including The Fortified Tower (2001), a 700+ page allegorical work about the delayed wedding of an Iraqi hero to a Kurdish girl, under the Arab name for Anonymous, ‘Written by He Who Wrote It’, and Begone, Demons (2006), describing an Arab army defeating a Zionist–Christian enemy by invading their territory and destroying a set of twin towers? Not being funny, Justin, but Picador never bid for any of Saddam Hussein’s novels, and neither did they offer to publish the United Kingdom TM. As inhabitants, not of The Fortified Tower or Begone, Demons, but of the United Kingdom, where political leaders mightn’t be quite as upfront about a) authorship, and b) the fact that capitalism is a system designed to benefit some at the expense of others, we depend on incongruities and irregularities in the official narrative, so-called ‘spaceship moments’, to confirm what we already know, namely that we’re alive in a substandard fiction that doesn’t add up. Justin Fashanu, you ever come across this expression, ‘a spaceship moment’? Didn’t think so, but know that, in Chachki’s and my Cataclysmic Foibles lexicon, a ‘spaceship’ is a moment in which discreet neo-authoritarian governance and deliberate governmental deceit become apparent, just momentarily, before vanishing again. What’s that have to do with your life, you might ask, Justin Fashanu, a gay, black footballer, but how the concerted bullying of an individual belonging to more than one oppressed demographic relates to the workings of state control is a pertinent question, and one I ask myself every day. You might be able to tell, Justin, that at this stage in my life, 06 or 07, my preoccupations were shifting away from you and towards stagecraft, if not spacecraft; I had friends, I had ambitions, my need for a stepdad diminished dramatically, but when in 08 or 09 the Justin Fashanu All-Stars football team was announced in the Camden New Journal as well as more prominent media outlets, along with a recruitment call, Justin Fashanu All-Stars Want You!, capital letters, it cut to the quick, it was the combination of Justin Fashanu and being wanted that did it, I, aah, cried like a baby, then walked out of Cataclysmic Foibles rehearsal, took the 214 bus from Pratt Street to Old Street, and sat outside Chariots Roman Spa for a day or two. Eventually, I mustered the courage to walk up to the triangular awning, past the fake Roman pillars, the plastic lions, and ask security whether they had any vacancies for assistants right now, I had experience, the stomach for it, and finally, finally, I was well over eighteen, I didn’t say that I already had, not one, but two jobs, as a cleaner on minimum wage and an unpaid playwright, and neither did I reveal that I hoped that seeing you weren’t inside, Justin Fashanu, that you’d never come out, would help me put you to rest for good, but closure wasn’t achieved that way, because Chariots weren’t recruiting, not generally speaking, but also, I was told that I still wasn’t ‘right’. Later I learnt that the Justin Fashanu All-Stars were connected to the so-called Justin Campaign against homophobia and transphobia in football co-founded by Brighton Bandits FC players and Juliet Jacques, then emergent writer and filmmaker. The way the campaign combined queer culture, art activism and football spoke to me, at least initially, I thought about joining but remembered my interest in football was limited to Justin Fashanu, the beautiful player, arguably at the expense of the beautiful game. Still, I was impressed, I imagined these activists building alternative worlds of amateur football through their campaign, if not for me, then for their All Stars; worlds where the tails and spikes of pastel dragons didn’t catch at every goalpost and corner flag, and where new socialities and support systems had a chance to originate and come to fruition. I imagined that the Justin Campaign did for its players what Cataclysmic Foibles did, is still doing, for Chachki and myself and our extended community. Ever since Cataclysmic Foibles helped me build a little world for myself, in London, I’ve wondered whether I really needed or wanted you anymore, Justin, at all. With love, Sterling.

Photograph © Adam Cohn

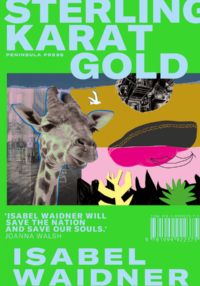

This is an excerpt from Sterling Karat Gold by Isabel Waidner, published by Peninsula Press on 24 June 2021.