Vasily Grossman’s relationship with his mother, Yekaterina Savelievna, was of central importance to him throughout his life. He dedicated his most well-known work Life and Fate to her. The most remarkable of his short stories (included in The Road) is titled simply ‘Mama’. And after his death, an envelope was found among his papers; in it were two deeply painful letters he had written to his mother on 15 September 1950 and 15 September 1961, that is, on the ninth and twentieth anniversaries of her death. She was one of 30,000 Jews shot by the Nazis outside Berdichev in September 1941.

Born in 1871 to a Jewish family, Yekaterina was brought up in Odessa, then a wealthy and cultured city where Jews constituted nearly 40% of the population. Her family seems to have been thoroughly assimilated. Like her three sisters – Maria, Anna and Yelizaveta – she was always called by an adopted Christian name rather than the Jewish name she was given at birth. She certainly had some knowledge of Yiddish, but whether or not she spoke it freely is uncertain. All four sisters were fluent in both Russian and French.

Yekaterina was born with a misaligned hip joint. In spite of this disability, she was clearly an unusually independent woman for her time. She studied in France. She married an Italian Jew, of whom little is known, and whom she left for Semyon Osipovich Grossman, a Jewish Ukrainian chemical engineer who had graduated from the University of Bern. Their son, Vasily, was born 12 December 1905 in Berdichev in Ukraine. Semyon and Yekaterina separated when he was still a baby. Yekaterina never remarried; Semyon did, but he had no other children. He and Yekaterina remained on good terms and went on writing to each other, and exchanging news about their son, for the rest of their lives.

Yekaterina taught French and loved French literature. When Vasily was five years old, she took him to Switzerland, where he studied for two years at a primary school not far from Geneva. What he learned there, and from his mother, remained with him throughout his life. Alexandra Popoff writes in her recent biography Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century, ‘Grossman would later read the French parts of Tolstoy’s War and Peace without translation and recite poems by Alfred de Musset; he knew by heart whole pages of Alphonse Daudet’s Lettres de mon moulin and of Guy de Maupassant’s Une vie, which was also his mother’s favourite reading.’

Little of the correspondence between Yekaterina and Vasily has survived, and few writers of memoirs have much to say about her. There is no doubt, though, that Grossman has portrayed her, as truthfully as he could, in his Stalingrad dilogy. Dates and minor biographical details have been changed, but the figure of Anna Semyonovna – the mother of Viktor Shtrum – is modelled on her. The only substantial difference is that Anna Semyonovna is not a French teacher but an eye doctor. Grossman himself was very short-sighted and his choice of profession for Anna Semyonovna is far from random. On the one hand, he is – half-jokingly – wishing he could have had more help with his eyesight; on the other hand, he is thanking his mother for the clarity of moral and psychological vision she has passed on to him.

What Grossman emphasizes above all in the two novels is the intensity of Anna Semyonovna’s love for her son. In a chapter about Viktor’s childhood, he writes, ‘Her friends had marvelled at the single-minded devotion she then showed to her young son. She became a homebody, seldom going out and always taking Viktor along with her when she did. And she only visited people who had children the same age as Viktor.’

Still more strikingly, on a separate page inserted into the typescript at a later date, Grossman writes, ‘There was one other constant in Viktor’s life, a quiet light that illuminated his whole inner world. It was his mother who had given him this light, but he did not realize this. She felt Viktor’s life was more important than her own; nothing made her happier than to sacrifice herself for her son’s happiness. For Viktor, however, nothing was more important than the science he served. He appeared gentle, incapable of saying a harsh word or acting coldly and brutally. Nevertheless, like many people with a sincere belief in the absolute importance of their work, he could be harsh and unfeeling, even merciless. He saw his mother’s love, and the sacrifices she made for him, as entirely right and natural. One of his mother’s cousins once told him that, when she was a young widow, a man she very much liked had tried for several years to persuade her to marry him. She refused, afraid this would prevent her from devoting all her love and attention to her son. She had doomed herself to loneliness. And she had said to this cousin, “It doesn’t matter. When Viktor’s grown up, I’ll live with him. I won’t be alone as an old woman.” Viktor was touched by this story, yet it did not move him at all deeply.’

Here, as often in his fictional self-portrayals, Grossman is fiercely self-critical. And he certainly felt profound guilt over his failure to act more decisively in the first month of the war, when he could have taken his mother from Berdichev to the relative safety of Moscow. Deep, lasting guilt with regard to such an irreparable tragedy is usually disabling. In Grossman’s case, however, his feeling of guilt seems, at least in some respects, to have strengthened him. At the very least, it seems to have made him all the more determined to make his Stalingrad dilogy into an adequate memorial not only for his mother but also for the many other people he knew – friends, fellow writers, teachers, close relatives – who had been executed during the purges of the 1930s. It perhaps helped him that his mother also passed on to him a very strong work ethic. Grossman seldom let a day pass without writing, and the doggedness with which he defended his work against officialdom is remarkable. In Stalingrad he writes, ‘Anna Semyonovna wanted both to indulge her son and to instil in him the habit of long, disciplined daily work. Sometimes she thought he was spoiled, capricious and lazy and, if he got bad marks at school, she would call him an idler, shouting out the German word Taugenichts!’ If, as seems likely, this is a childhood reminiscence, then Grossman’s mother certainly achieved her aim.

Grossman pays tribute to the strength of Anna Semyonovna’s own determination to keep working: ‘On the days she didn’t go to the clinic, she gave French lessons in her home to children from local families. Viktor used to beg her to give up work altogether, saying he would send her 200 or 300 roubles each month, but she said this might be difficult for him. […] The main thing, though, was that she needed to work. She had worked all her life, and without work she would go out of her mind. Her dream was to go on working until the end of her life.’ The Stalingrad dilogy is full of delicate, yet powerful ironies, many of them too subtle to be apparent during a first reading. In Life and Fate, in the last letter Anna Semyonovna sends Viktor before her execution, we see that she did indeed realize this dream, only in circumstances more terrible than she could ever have imagined. She goes on working during her last days in the Jewish ghetto, doing what she can, without medicines, to help her fellow Jews with their eye problems.

Grossman did not, of course, receive a ‘last letter’ from his mother, but he did, in 1946, receive some information about her last days in the ghetto. She lived with the family of one of the Berdichev doctors and taught French to his children, reading a French translation of War and Peace. One of this doctor’s daughters somehow survived. She witnessed Yekaterina’s last days and spoke about them to her cousin, Rosalia Menaker. In 1946 Rosalia – who worked as a midwife and had been present at Grossman’s birth – sent Grossman a letter, telling him all this.

In September 1950, in the first of the two letters he wrote to his mother after her death, Grossman recounted a dream he had had in September 1941, and which he had already recounted in Stalingrad. There, of course, it is dreamed by Viktor Shtrum – yet another testimony to the autobiographical quality of so much of Grossman’s work. In the letter to his mother, Grossman writes: ‘I entered a room, knowing that it was your room, and saw an empty armchair, knowing that it was where you slept. Draped across it was the shawl you used to put over your legs. I looked at this empty armchair for a long time; when I woke from the dream, I knew that you were no more. But I did not know what a terrible death you had died; I learned about this only when I came to Berdichev and questioned people about the massacre that took place on 15 September 1941. I have tried dozens, perhaps hundreds, of times to imagine how you died, how you walked to your death. I have tried to imagine the man who killed you. He was the last person to see you. I know that you were thinking about me a great deal – all this time.’

And in September 1961, a year after completing Life and Fate, he wrote:

‘During these twenty years many people who loved you have died. You no longer live in Papa’s heart, nor in Nadya’s, nor in Auntie Liza’s. All are gone.

‘And it seems to me that my love for you is all the greater, all the more responsible, now that there are so few living hearts in which you still live. I have been thinking of you almost all the time, almost all these last ten years that I have been working; the love and devotion I feel for people is central to this work, and that is why it is dedicated to you.’

Stalingrad, the first half of the dilogy that includes Life and Fate, is translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler, and published by Harvill Secker on 6 June 2019.

Feature photograph courtesy of Yekaterina Korotkova-Grossman

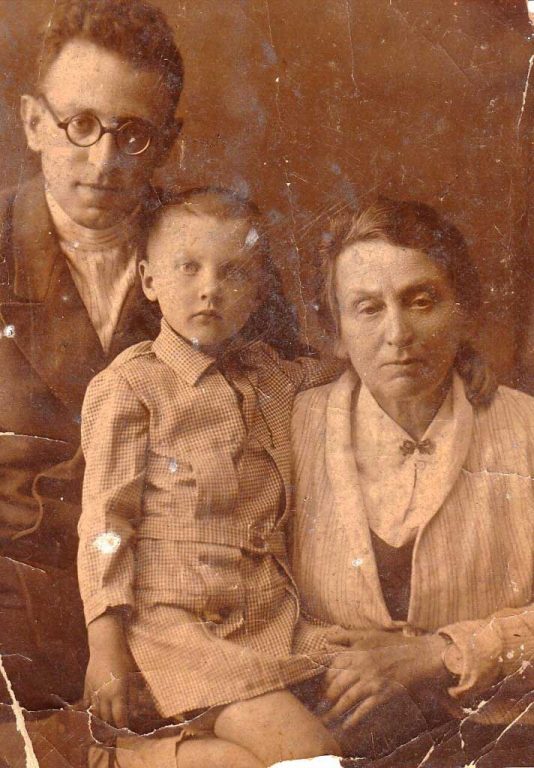

In-text photograph courtesy of Tatiana Menaker