If there is drama in John Berger’s story about the killing of a pig, there is very little suspense. At the heart of Berger’s book Pig Earth (1979), the fictional fruit of his time living among a peasant community in France, Pépé, the protagonist’s grandfather, announces to his family that ‘tomorrow we are going to kill the pig’. In the sequence that follows, every character, pig included, is shown to understand their role.

The pig, until then, has complied with being fed ‘like one of the family’, albeit one who is destined for the chop. But now, at a quasi-majestic hundred and forty-two kilos, his feeding days are up. Seeing grandma in the kitchen doorway without her bucket of food, he immediately perceives his fate. For the very first time, he hesitates, then lunges and kicks, ‘like a man’, like ‘a man fighting off robbers’.

They say it takes a village to raise a child and the same can be true of killing. Neighbours assemble to help with hauling the noose around the pig’s neck, to resist the force of his gigantic hams and midwife his surrender with their fists. ‘During the next twelve months’, the child-narrator explains, ‘he was going to give body to our soup, flavour our potatoes, stuff our cabbages, fill our sausages. His hams and rolled breast, salted and dried, were going to lie on the rack, suspended from the ceiling above Pépé and Mémé’s bed.’ The pig is both loved and lamented by those who would otherwise starve. The fatal cut is made and his screams become deep breaths.

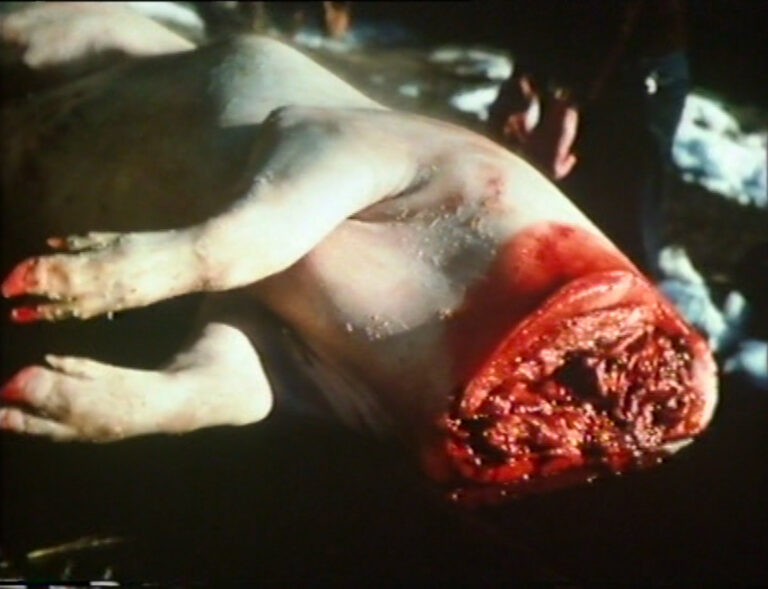

One of the most striking images in the film adaptation of Pig Earth is that of the pig’s head, its severance the decisive moment of becoming meat. As stills of the annual slaughter mount onscreen, we witness the smiling corpse as he is hauled onto a sledge. One moment his head is attached to a recently animate being, the next it is a thing – a manufactured theatrical prop.

Such props are not unfamiliar in visual culture of meat. In Western theatre, perhaps the most ubiquitous head to be seen is that of Pentheus in Euripides’ tragic drama The Bakkhai. In that play, first produced in 405 bce, the King of Thebes and his mother are punished for refusing to acknowledge Dionysus, god of nature and its pleasures, horns on his head and snakes in his hair. Dionysus lures the women of Thebes (including King Pentheus’s mother Agave) into the mountains where he gets them high. Having done so he invites a fusty, disapproving Pentheus up there with him to confront the women face to face. It is there, through his female followers, that Dionysus will harvest revenge. In true tragic style, it is Agave herself who will glean her son’s head from his body.

When Agave finally tears the head of her beloved son from his neck, she is apparently ‘out of her mind’. She does not hear him identify himself as she plants her foot on his chest and rips the meat from his bones. Picking up his head and impaling it on a stick as though it were a mountain lion’s, she crows with pride at her hunting success and descends to display it for her son. Finally, in one of ancient Greek theatre’s least watchable comings-to, she sees what she has done and howls, herself most painfully undone. Berger’s peasant child howls too when he wakes the day after the killing to re-witness the head he was handed and dutifully put on ice. He howls as he is properly acquainted with the frozen face of the ‘family’ he helped to dispatch.

As with pigs and peasants, there is always a loser in the tragic exercise of power. The drama crests at that moment of realisation on the part of the ‘weak’ that things are about to go south. It is tragedy’s most awful treat to its blood-lustful audience that attempts at love are set on a relentless course to culminate in meat. If meat and love are by any indomitable force brought into contact, that force is typically violent.

As Berger himself puts it in the afterword to Pig Earth, ‘However much a bad harvest is considered an act of God, however much the master/landowner is considered a natural master … the basic fact is clear: they who can feed themselves are instead being forced to feed others.’ By ‘peasants’, he refers to those whose ‘surplus’ production of food is a condition of their survival. Like the produce of pre-enclosure peasants, which went first to a lord and the remainder to the peasants themselves (on which they hoped to subsist), that which is produced by the modern peasant is gobbled by the market economy. Peasant life, Berger writes, is characterised by rituals and routines that attempt ‘to wrest some meaning … from a cycle of remorseless change’ – a cycle which, by the time of his writing in the 1970s, consists of feeding an unwieldy economic system.

Indeed, with the intensification of capitalist production comes the intensification of both human and animal exploitation. The early needs of industry led to the mass displacement of peasants; later the needs of industrial agriculture led to the mass expropriation of their land, cheap labour, and food. The present agricultural order, equally driven by growth, must find ever more technologised ways to destroy the planet, human wellbeing, and animal life. Global meat production has more than tripled since the time of Berger’s writing, and is predicted to double again in the next thirty years. Modern capitalism’s separation of life from nonhuman nature, recruiting animal and land into the process of profit-driven manufacture, has culminated in a fossil-fuel-dependent, land-hungry, chemically fertilised frenzy of animal cruelty, organised by a corporate class with relatively little motive to care.

However they are eventually killed, the farmed female pigs of today may swell at human hands to over two hundred kilograms only to live their fattened lives in the modest spaces those hands apportion. The least fortunate gestate their young in cages or ‘crates’ and wait to be inseminated again, never long after their piglets have been taken away. When they are sent to be killed, pigs of either gender are often stuffed into holding crates, squealing in dissent as they go. Once they have been stunned and hung up from their legs, they are finally stabbed in the neck, after which point they continue to struggle for further tens of seconds.

Stills from Pig Earth, directed by Mike Dibb, 1979

In the era of Pig Earth in the Europe Berger describes, the urban industrial workforce and middle-class diners alike were united in a certain insulation from the facts of rural life. If industrialisation had introduced to the ‘citizen’ security, permanence, protection – in the form of heating, transport, laws, and other such defences against nature’s vicissitudes – so had it also shielded their hearts and minds from the realities of animal farming. The cosseting of this citizen had now become so ‘total’ as to suffocate imagination of the land. ‘Alone in a serviced limbo’, to use Berger’s terms, the urban consumer, having never been expected to love the pigs he would eat, could no longer even be expected to acknowledge their having lived at all.

Berger warns any reader liable to be rapt in bucolic nostalgia against romanticisation of the lost peasant class. He is loath to brandish the peasant as an idol to be preserved, since to do so would preserve his exploitation. Nevertheless, he fears what it might mean for humankind to obliterate manual farming. Where previously cities were dependent on the countryside for food, soon, Berger predicted, the countryside would be dependent on the cities for the means of survival. This would mark an end for the peasant’s unique understanding of the real ‘value’ of nature, the cost to the earth of capitalism’s use of land and life. It was Berger’s prediction in the late 1970s that another twenty years would unfold in a similar direction to that which he had seen in the 1950s and ’60s.

Yet in fact, twenty odd years from then, if an urban citizen of the industrialised West thirsted to return to the land, a media movement was rushing to meet them in their home. In the UK, for instance, the metropolitan consumer needed look no further than Channel 4. It was there, in 1999, that the charming urban cherub named Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall took to the screen to help popularise, or perhaps reconstruct, a dwindling smallholder consciousness. In the series Escape to River Cottage, we follow Hugh as he moves from London to Dorset to model the labours of small-scale farming, throwing himself into a life of building and growing, bartering and market-stall hawking, and raising and ‘finishing’ livestock. If the witlessly insulated urban dolt lived a life surrounded by supermarket meat – slabs of glistening pastel pink so far from the blood of butchery – Hugh was here to show us where that alienated flesh expressly hadn’t come from. Hugh was here to save our souls from financing the bloodbath of factory farming, guiding us instead to lovely River Cottage, a stable of animal love.

How does one raise the consciousness of automated, meat-pumped yuppies to register the love of the farmer, at least the ‘good’ one, for his pig? Hugh, an Eton- and Oxford-educated man, elected, as I have, to reference certain classical aesthetics. Having witnessed his purchase of two nice hogs at the start of Escape to River Cottage, six months and six episodes later, a finely wrought tragedy concludes.

Tragic doom is signalled from the first in Hugh’s casual invocation of fate. Specifically, he is anxious re: the ‘logistics of the fate of his pigs’. It is common in tragic drama for destiny to roll its tyres over rational deliberation. ‘What should I do?’ a character asks, though no amount of reasoned debate, in this genre, can lead to a happy resolution. New European legislation ordains that pigs raised for sale can no longer be killed at home, and must therefore go to an abattoir. For Hugh, the matter for internal discussion is whether to go with them.

He seems to think he has been spared the ordeal of choice when it comes to the biggest question. The question of whether or not they should be killed at all is never a subject for discussion. He needs their meat, he claims, for his winter store, and to pay back some neighbourly debts. Since pork is his prime currency, the slaughterhouse it must be. Conjuring a quintessentially peasant-shaped situation of both economic and nutritional need, Hugh opts to immerse himself fully in all the drama of mortality. ‘I was there at the beginning’, he concludes in a one-man choral lament, ‘and I feel I ought to be there at the end.’

In Greek drama, such heroics typically lay the foundation for an imminent ‘reversal’: some plot-driven horror that will prove our otherwise reasonable protagonist wrong. Not that there is ever anything a hero can do to avoid the tragic conclusion. Like Clytemnestra in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, Hugh sets out on a slaughterous course that is reduced, in narrative terms, to the fulfilment of rituals choreographed by gods. When Hugh builds a tunnel-visioned, slip-proof bridge that will lead the pigs into the back of a truck, it is as though to re-enact Clytemnestra’s rolling out of the original red carpet. It was only through the lure of said carpet that she could guide her husband, the titular King Agamemnon, to his death, which she deals him in retribution for his sacrifice of their daughter. While the King had acted under duress (divinely punished for an ancestor’s child-eating crimes), he is nevertheless blamed for having laid his progeny out ‘like a goat-kid over the altar’. Disputing this treatment of human life, of kin no less, like a beast appropriate for murder, Clytemnestra resolves to lay her husband out for sacrifice in the bath. Instead of Hugh’s straw, she strews the way with beautiful fabrics and bids her love step inside a house that is thoroughly cursed. Clytemnestra needs nothing but flattery to lubricate the will of the gods. Hugh, having underfed his swine in advance of the special occasion, must tempt them with a bucket of pignuts.

When we next see Hugh’s pigs, or more accurately their hams, being salted in the River Cottage bath, the proxy-peasant remarks on the resemblance of the scene to a ‘bizarre religious ceremony’. And yet, for all its air of sacrificial pomp, the stage is utterly bloodless. As in Greek tradition, the killing itself does not take place within view – Hugh’s pig trailer simply disappears into a gleaming tunnel of thickets – yet nor is there a monologue recounting the act, a typical tragic dénouement. Rather than put too literal an image to ‘where the meat comes from’, the emphasis swivels instead to how it is tenderly carved into bits.

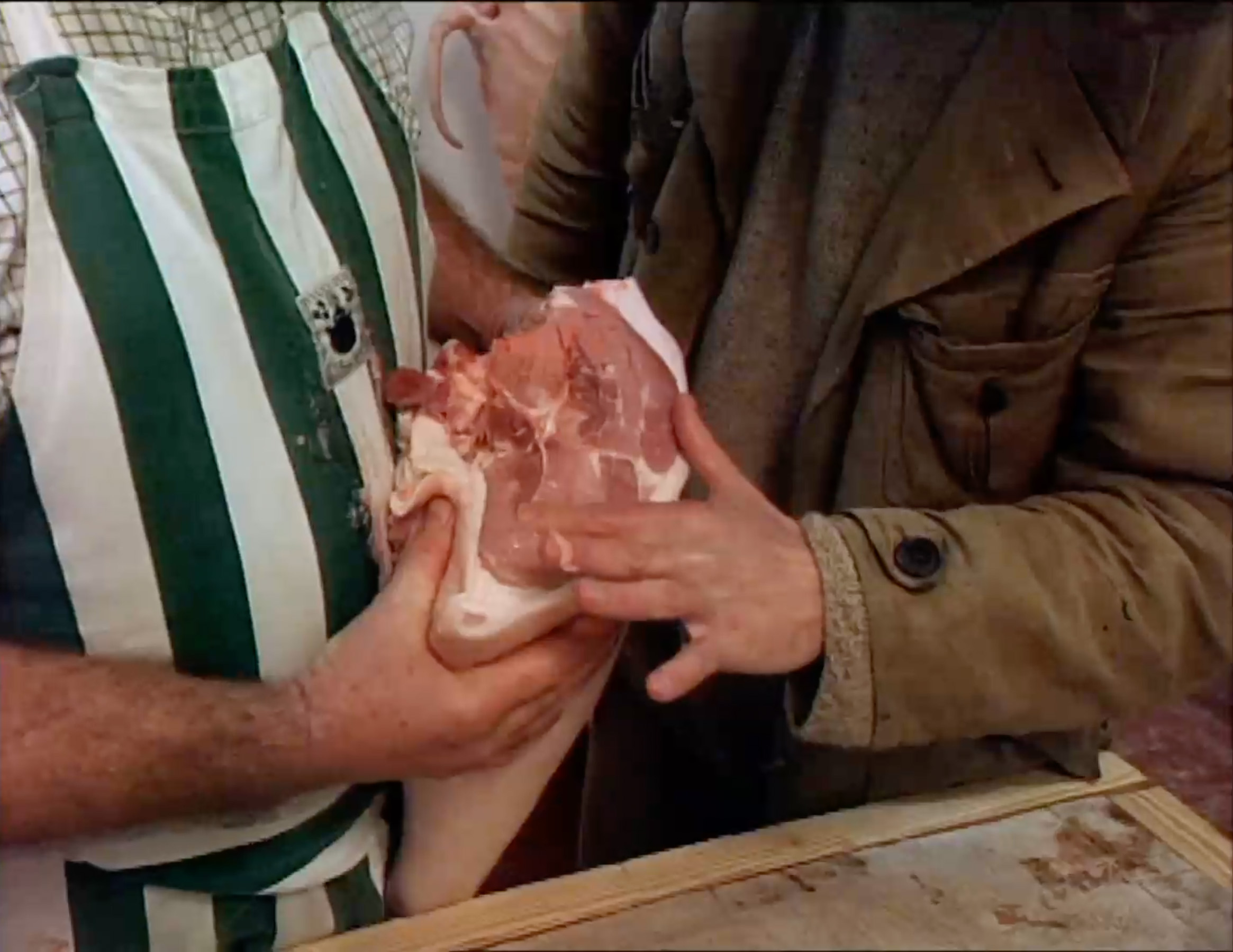

Stills from Escape to River Cottage, directed by Billy Paulett, 1999

Myriad opportunities here arise to congratulate the loving butcher. In the tragic form it is often bragging, or hubris, ‘excessive boldness’, that symptomatises the poverty of human self-knowledge, always with devastating outcomes. Pentheus shows hubris in wielding his kingly power unaware that he is dealing with a god. Agave is hubristic in the carefree ripping spree that leads to a dismembered son. Agamemnon is hubristic in thinking he can return to a wife whose daughter he has killed. She too is hubristic in killing him, and will later be killed by their son. For Hugh, only a ‘tinge of sadness’ goes hand in hand with what he describes as ‘a fair measure of pride’. Yet pride is here stripped of any possible connotation of excess. Indeed, we bask in it warmly. Hugh would like to think, he muses, that he has raised ‘two of the happiest pigs who ever lived in Dorset’. What fun would it be to disagree?

Despite, then, Hugh’s tributes to tragic ideas of humanity and fate, the programme gives little sense of there being any kind of victim. Once he has strapped on the yoke of that fateful tragic killing, the ‘loser’ is neither the exploited peasant farmer who loved his pigs nor the pigs who loved to be alive. As the butcher helps our cheerful smallholder, only electively in debt, to make sure he uses every last scrap of meat, he remarks of the gaping bodies that now hang from the River Cottage ceiling that they’ve obviously been very well fed. In what follows each gleaming cut is cleaved into abstraction and thrust before the camera, almost as though it were a birth. As we swallow the visual goodness of this ethically farmed feast, Hugh himself stops to gaze upon the culinary potential of ‘the noblest and tastiest animal ever reared for food’.

‘Cooking is a daily drama’, writes Hugh himself in the introduction to his biblically authoritative 2004 tome on River Cottage Meat, ‘still staged in almost every home.’ Meat eating at its worst (i.e., the eating of what is affordable, readily available, farmed with state subsidies, and culturally sanctioned) is, for Hugh, ‘an ignominious expression of greed, indifference, and heartlessness’. By contrast, the smallholder’s face-to-face confrontation of death is of no such moral or political consequence. No hubris taints this happier brand of tragic philosophical drama, on the grounds that, in the absence of sadist brutality in the method itself, there is nothing inherently wrong with killing if the victim isn’t human.

Indeed, unlike in tragedy proper, the world of ethical meat defies any sense of blurriness in human/animal boundaries. Instead, it displays the perspective of an eternal human victor, appointed, of course, by the human himself. Hugh presents this perspective as something of a logical given. ‘For hundreds of thousands of years we have hunted animals’, he writes, ‘and for tens of thousands we have farmed them, so that we can eat their meat … There is continuity in our meat eating and it is, in some deep-rooted, even hard-wired, way, natural.’ And yet, he notes, for all our natural continuity with animals’ carnivorous habits, our genteel manner of killing is markedly different from theirs. Counting no Agave among humankind, Hugh points out that we humans restrain ourselves from chasing down animals and ripping them with claws. Instead, we ‘prod and poke them into a reasonably orderly queue’ before stunning them into submission and dispatching them. Everyone, farmer and pig, is seemingly here at peace with his timeless, god-given role. Hugh the humane is precisely animal enough to justify killing other beings, yet humanly distinct enough to justify a claim to beneficence in doing so.

This is an extract from Meat Love: An Ideology of the Flesh by Amber Husain, published by MACK in 2023.