Means of Transport

John Berger

To learn how to speak –

With the voices of this land. –Jeremy Cronin

Use these photos as means of transport. Ride on them. No passes needed. Go close. Imprudently close. They leave every minute. Their drivers are there on the spot – often at considerable risk to their cameras and themselves. But we who are travelling risk nothing – except a reminder that justice has to be fought for, that often it has to be fought for, generation after generation, against men armed to the teeth and against men, there where the photos take us, who have even manufactured a nuclear bomb to defend their wicked white power. Go close.

The statistics inevitably have to be calibrated from afar. Four-fifths of the population there – that is to say over twenty-five million souls – have no vote. Continually displaced, they do not have the right to live or work where they choose. Under the apartheid laws they are restricted to thirteen per cent of the poorest land, the so-called ‘bantustans’, where economic survival is impossible. Those who leave to try to earn a living for their families become – unless they have a temporary contract – illegal immigrants in their own country. Many in the shanty towns on the edges of the cities remain unemployed. Those who do get work constitute one of the most exploited industrial labour forces in the world.

The white minority have an average life expectancy of 73.9 years: the four-fifths majority a life expectancy of 59.8 years. In the country of the first heart transplant, 50,000 black children die every year from malnutrition. But hunger, comes the evil reply, is endemic to Africa! Last year in South Africa more than 2,000 children were imprisoned with their mothers. Is imprisonment too endemic to Africa? Take the photos and go close. Imprudently close.

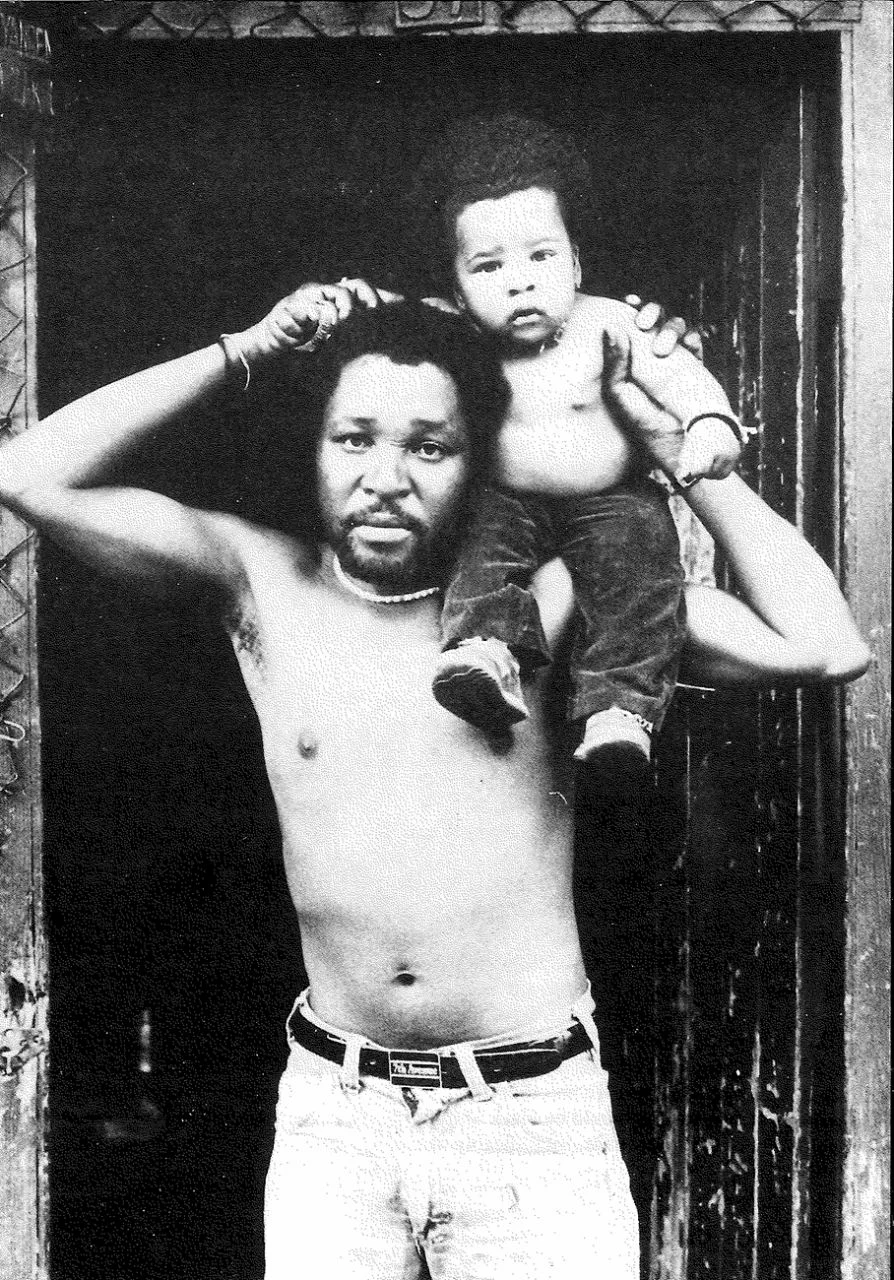

Women and men come to the doors of the shacks where they live. They look at the camera. They look at us visiting. They are sombre. On one shoulder a man carries the weight of the past, on the other his child. Beyond all the universities in the world these women and their children and men embody history. And they know it.

Love life. Be like the sunlight afforded this earth and love life. Not because life in this prison state of apartheid is lovable, but simply because all that is lovable comes from life. Get down at Crossroads, the squatter-camp near Cape Town. Everyone is there illegally. Their homes will be burnt down. The land will be cleared. They will be evicted, driven out, beaten up. They have nowhere to go. On nowhere they built homes. Look at their children. Like children everywhere they have been given a name. Unlike children in most places, many will also be given a number soon, a number on the police computers. See. Their parents have given them space, the space to be themselves within their name; they are loved. Parents who don’t have a single square metre to sit down upon or to call their own have given their children space. The Casspirs, the riot vehicles, can’t evict from the heart. Here the Casspirs are powerless.

Marx’s vision that the proletariat would become increasingly impoverished and exploited until it had nothing to lose but its chains and that the capitalists would become increasingly and disproportionately wealthy has been proved false in all the industrialized countries of the world, except South Africa. Here his prophecy is being realized. What Marx couldn’t foresee was that the proletariat would be black and the capitalists white. Ineradicably true.

In a home, made of tarpaulin and corrugated iron and wrapping paper, a broom leans against a wall, and the woman of the house, built on nowhere, will take it to sweep. In an official barrack built for migrant workers, hundreds or thousands of miles away from home, of women there is only talk. Between the single bunks the promise of normal family life is like coconut milk in a hand-grenade.

Yes, there is resistance. And fear too. How could there not be fear? Better to ask when getting down at the barracks: how to live with fear and sometimes overcome it?

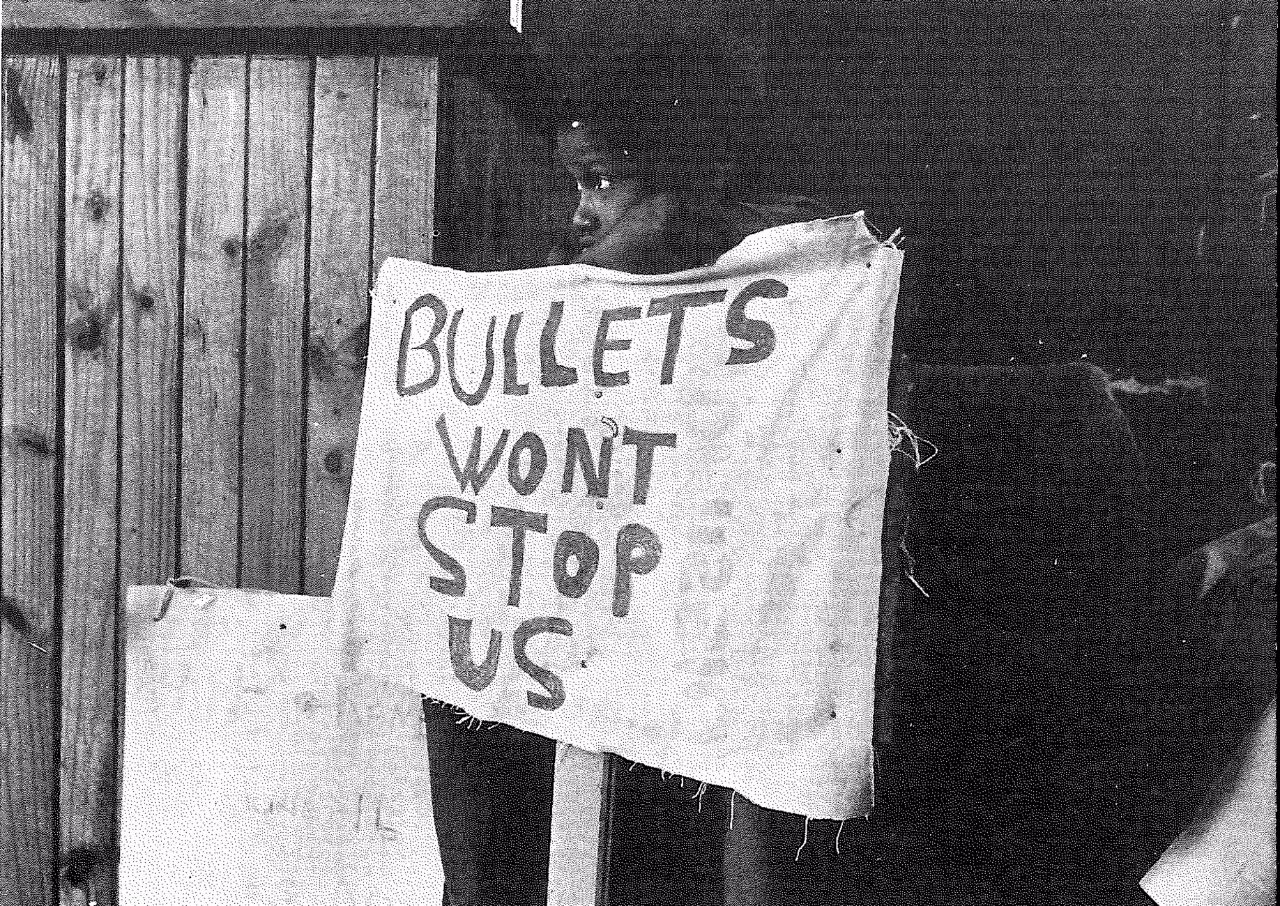

In the new coffins of the newly assassinated there are young bodies but also the entire history whose weight is on every black shoulder. At the funerals the words: BULLETS WON’T STOP US are written. When the young believe in what they have seen and live this belief, their beauty makes them unstoppable.

More can be shot dead of course. But then, as martyrs, their beauty becomes immortal.

None of this for one instant diminishes the pain of the whip or the grief of the mother or the despair of the mutilated. Not for a single instant.

The stormtroopers are in the streets –

the women wash dishes with their tears. –Hein Willemse

Come closer. Reckoning consequences and the rules of cause and effect belongs to a calculation that cannot be found here. Here there is nothing to the future except hope. That hope is beautiful. But apart from this hope, the future is already devastated, a continuation of the catastrophe of the past whose weight is on every shoulder. Here there can be no consequences as calculated elsewhere. Only hope and her brother fear. And this – which is hard for visitors to understand – is why the kids write and will go on writing: BULLETS WON’T STOP US.

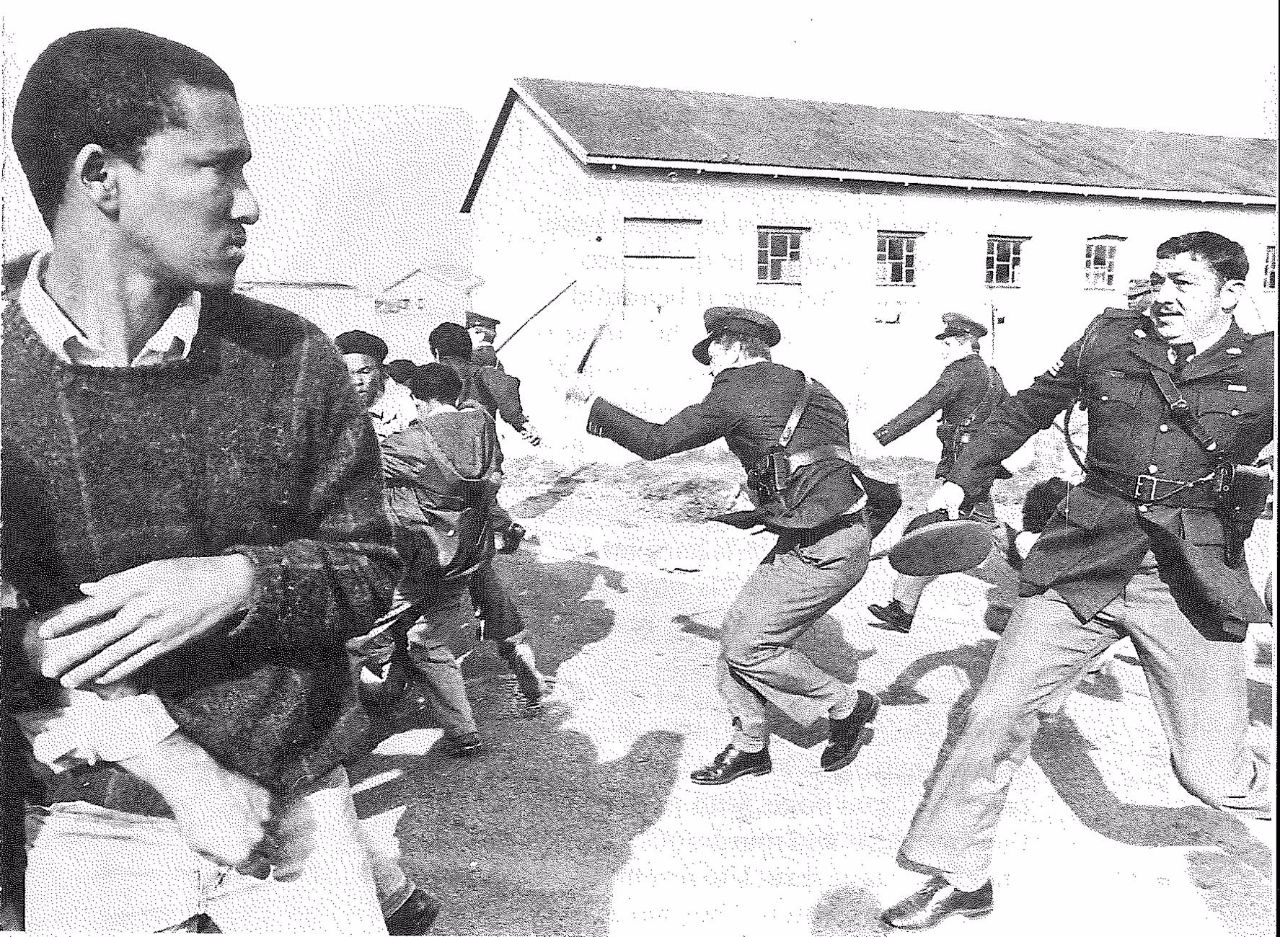

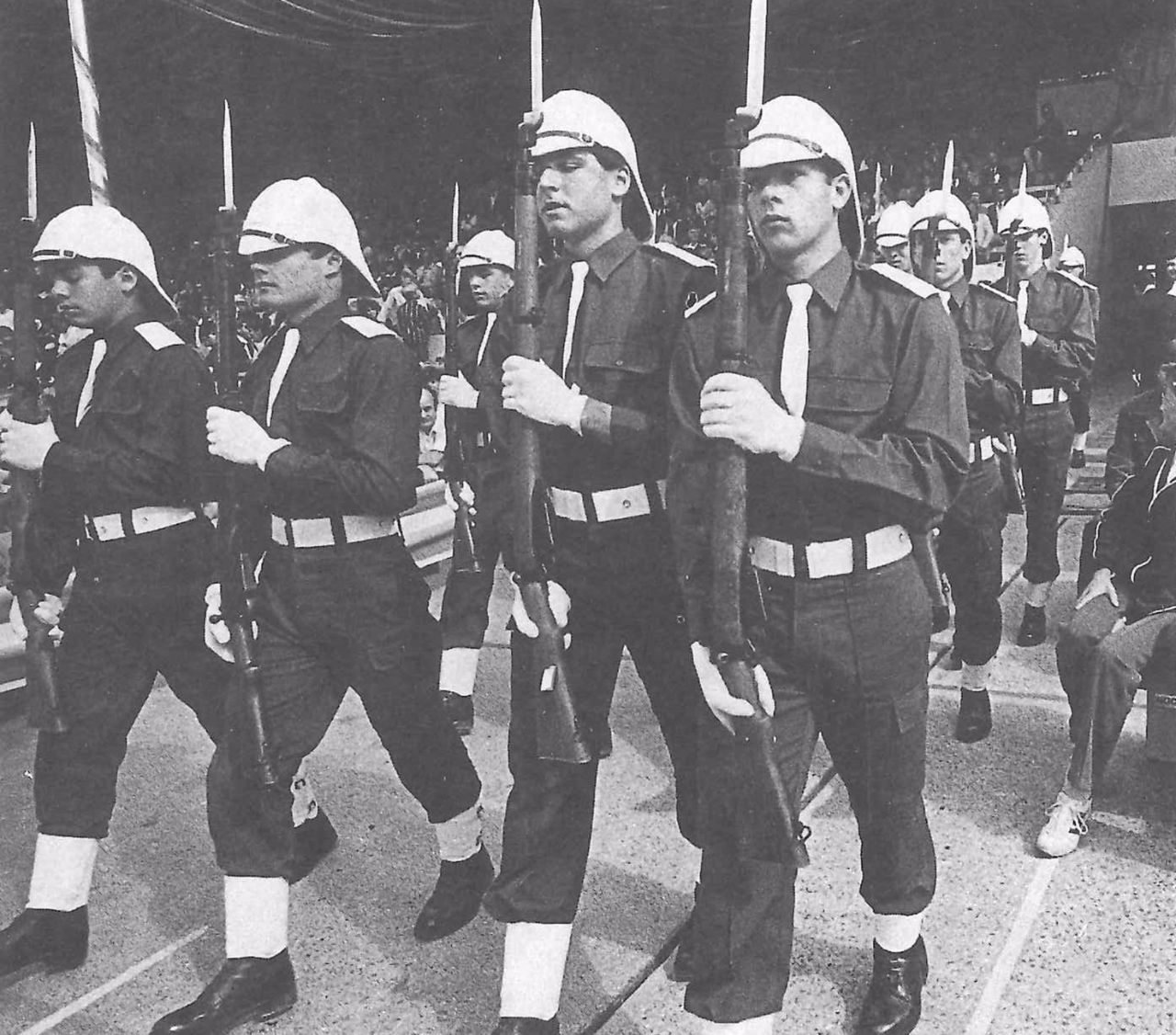

Get down now at one of the military parades. Those in the uniforms are damned. This is visible in their faces. Without hope, with nothing but their weapons and murderous orders, their faces have shrunk to resemble the hams of pigs. Watch. They have everything. The wealth of the country, bullet-proof protection, property, homes, united families, servants, bank accounts, beaches, yachts, a life expectancy of seventy-four – and they have no hope. If it happens that they love somebody, all they can offer their loved one is to take their weapon, load it and wait. They own everything and hope has abandoned them. They have all become their own henchmen, yet today there is no one left for the henchmen to protect. The ruling class has become the killing class.

The killing class can’t sing. The homeless do.

Lady Day, Lady Day, –

Lady Day of no happy days, –

Who lives in a voice –

Sagging with the pain –

Where the monster’s teeth –

Are deep to our marrow. –Keoropetse Kgositsee

The killing class print out lies and make up new legal terms. They parrot. They curse. They issue orders. Yet the gift of words is a thing they can no longer acquire. And this is why they are frightened, not of lions or leopards or anything that can be shot, but of words.

Here is another squatters’ camp outside Cape Town, which is the port of what the colonizers once called the Cape of Good Hope. The KTC camp. In a make-shift shelter a family on a bed. They have no work and no pass, which means that on this bed they are illegal. They have already been evicted from other ‘shelters’ thirty or forty times. The mother is wearing a Scottish plaid recalling other evictions in another country. Their shoes are arranged under the bed. A clean newspaper on the table. Cloths neatly folded. One has flowers printed on it. In this shelter, constructed from discarded packaging, a home has been improvised. They are not looking at their visitors. From them they expect nothing. They are remembering. Something else.

The Ancestors invite us to the vision of the river. –

Knowing we have suffered enough; –

Through them we float aimlessly on a dream –

And yet our names must remain hidden from total joy –

Lest through weakness we may succumb –

Falling slowly into the depths of mindlessness, –

Our love must survive through the ancient flames. –

We must congregate here around the sitting mat, –

To narrate endlessly the stories of distant worlds. –

It is enough to do so, –

To give our tale the grandeur of an ancient heritage –

And then to clap our hands for those who are younger than us. –Mazisi Kunene

The dead fight too. Their innocence is fighting the guilt of the killers. This guilt is such that the killing class cannot tolerate the colours of a flag which accuse them. Study the face of the officer of the riot police at Ashrey Kriel’s funeral. The flag he is trying to tear off the coffin is that of the African National Congress. He believes that people can be torn up like paper. One day he will tear things up in his own home. Unlike the family in the KTC camp he can cherish nothing any more. He has lost the faculty. His hands can only grasp or wring.

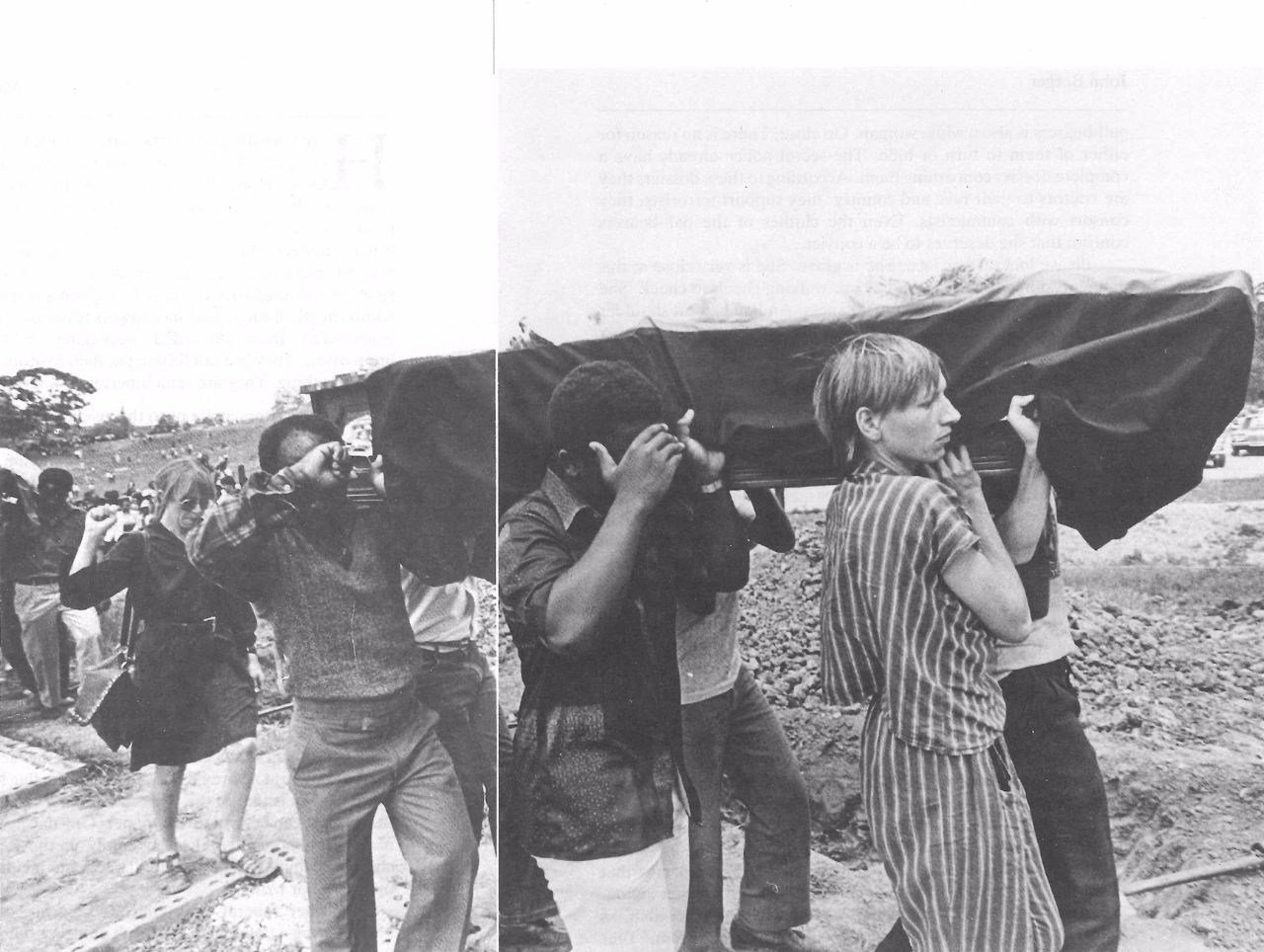

Another funeral. This time in Lesotho, of ANC members killed during a police raid. The first mourner following the coffin is a white woman. She holds up her clenched fist. Her gesture is so vulnerable and yet it declares: resistance and victory. One of the pall-bearers is also a white woman. Go close. There is no reason for either of them to turn or hide. The secret police already have a complete dossier concerning them. According to these dossiers they are traitors to their race and country: they support terrorists; they consort with communists. Even the clothes of the pall-bearers confirm that she deserves to be a convict.

Please look at her face. She is grave. She is very close at this moment to her conscience. They are walking cheek to cheek. She has chosen another kind of homelessness. And on her left shoulder she has chosen to carry the weight of history. I hope I will never forget this photograph. It was taken in the future, on the far side of barbarism.

This is Mayfair railway station in Johannesburg. A group of miners are waiting for a train to take them home. Their twelve-month contract working for the gold companies is over. They have become illegal again. They look tired, cold, disoriented. These are the men who extract from the earth the very symbol of wealth, the magic substance of the alchemists. Their brothers do the same for diamonds. Facing them, we stare at what hierarchy means. Under the earth they are at the bottom, near disaster: what they produce goes exclusively to the top. The photo was taken more than thirty years ago.

In 1985 the Congress of South African Trade Unions was launched. It is the largest trade union body in Africa. In 1987 it adopted the Freedom Charter for democracy.

Visit a strike today. The workers are listening to a speech. They are an audience, seated, their eyes on a stage from which they are being addressed. Study their expressions more closely. Each one knows that they are the actors too and that an invisible audience is watching them. Among this second invisible audience are hired killers, spies, police-chiefs, informers. But also in this second audience are all the prisoners of history, waiting to break out. No single person can decide the day. The day will come.

The meaning of the word CHAIN will be changed into that which links and joins. Not by decree but by freely chosen action. ‘An artist,’ said John Muafangejo, an engraver from Namibia, ‘is struggling with chains in order to tear them from the stem.’ Tear them from the stem.

Stop at the concert in Alexandra township. The poet ‘Jingles’ is performing to drums. He is looking over an invisible wall which is everywhere. He’s reminding people that on the other side of the wall the land stretches to the horizon. He’s showing that one can speak over the wall and be heard. Soon after the concert ‘Jingles’ was assassinated by unknown gunmen. Here art is not protection.

A daughter touches the hand of her arrested father as he is shoved into a car to be carried off. Remember the gesture of her hand. It is one from which nothing can ever be torn away, for it accompanies, accompanies wordlessly in the disappearing car, in the cell, in the courtroom. At this instant of brutal separation, there is a joining by faith.

Of course we never get to speak, –

As such, to each other. –

We’re still fifty yards, one corridor, –

Many locked locks apart. –

Jeremy Cronin

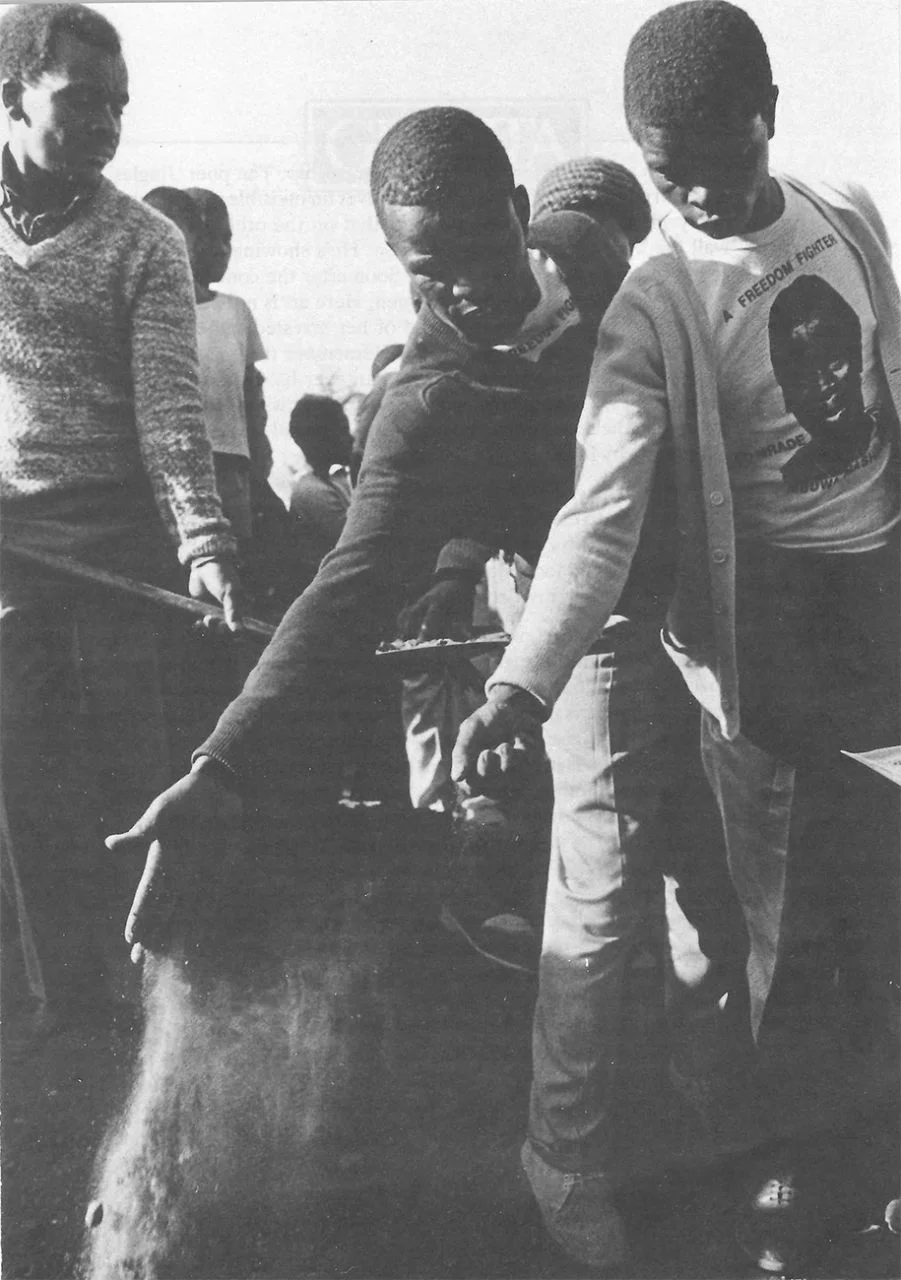

Two young men, wearing Freedom Fighter T-shirts, cast their farewell earth into the grave of a killed comrade. Their heads are bowed, for the comrade has gone for ever and his likeness will never occur again. He is irretrievable. A terrible word when spoken with love. Yet the gestures of their hands throwing the dust are deliberate. One is holding the earth for the last time before casting. The second hand is straight and has cast. Both of them very deliberate. They know exactly what they are doing. They are joining the living and the dead so that their hopes, becoming the same, will be irrepressible.

For the transport back to where we live any publicity photo in any colour magazine will do. Express non-stop service. All classes. Dogs allowed. But no History.

Photographs © Jenny Gordon, Paul Weinberg, Omar Badsha, Ian Mendel, Billy Paddock, Paul Grendon, Gideon Mendel, Paul Weinberg