This story deals with topics that may cause trauma invoked by memories of past abuse for survivors and intergenerational survivors of the residential school system.

Dennis spotted the cigarettes on their dorm supervisor’s bed. He hesitated a moment, then stuffed the pack of Rothmans King Size into his shirt pocket. No one was around to witness the offence except his two best friends, Jack and Bernard. The rest of the boys in Stringer Hall, their residential school dormitory, were outside playing. Dennis, Jack and Bernard shot out the front doors and past the playground to find a quiet place to smoke. The warm Arctic sun, which would not set for a few more weeks, hovered in the sky above them as they passed around a cigarette.

It was 24 June 1972, a Saturday, and in a week the three boys and their classmates attending the Sir Alexander Mackenzie School in Inuvik would head home to their small hamlets across the Arctic for summer break. By seven o’clock that evening the boys were back in the dorm. Their supervisor, Annie, was in a rage. She demanded to know who had taken her cigarettes.

Dennis eyed Bernard from the far end of the dorm. He looked frightened, and shook his head, signalling for Bernard not to say anything. Punishment at residential school could be severe, especially for stealing. But Bernard would never snitch on Dennis.

The next morning, after chapel, Bernard overheard a few of his classmates telling Annie they knew who took her cigarettes. They’d been caught. Bernard ran to find Dennis and Jack. He found them in Grollier Hall, the Roman Catholic dorm, and suggested they hide somewhere. They walked into the hills behind their school, sweating under the hot sun, until they found a pond. They waded into the cool, shallow water with their clothes on, splashing each other and laughing. Dennis still had the cigarettes in his shirt pocket. They were ruined now.

From the pond, the boys walked in the direction of the highest hill, where they could see power lines unspooling to the north-east. The 69,000-volt transmission lines had been strung the previous month. ‘These lines go all the way to Tuk,’ Dennis told his friends. He and Bernard were from Tuktoyaktuk, on the shores of the Arctic Ocean. If they followed the power lines, they’d be home in a few hours, Dennis said. School would be over soon anyway, and if they left now, they could avoid getting in trouble.

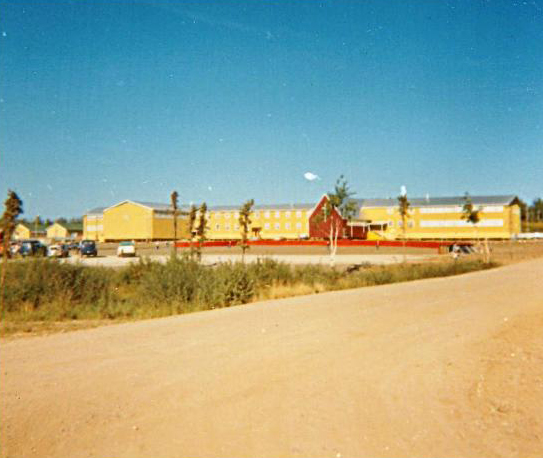

Stringer Hall, Sir Alexander Mackenzie School, Inuvik, late 1960s.

They took one last look down the other side of the hill towards Inuvik and began walking under the power lines. Around them, delicate flowers bloomed among the moss, and sharp blades of grass scratched their ankles. They joked about how tough they’d be by the time they got home.

Dennis and Bernard were cousins who’d grown up together in Tuk. At thirteen, Dennis was squat, and still waiting on a growth spurt. Bernard, though only eleven, was taller, and had long limbs outgrowing his torso. His hair fell messily onto his forehead above long, almond-shaped eyes. Jack was from Sachs Harbour, a town on Banks Island, the westernmost island of the Arctic Archipelago. He was the smallest of the three, and prone to illness, especially at residential school where the children were stuffed into close quarters.

Hours later, the midnight sun was low on the horizon, reflecting off a glassy lake. Its glare was now soft. Ahead, Dennis saw a familiar formation. ‘Look,’ said Dennis. ‘There’s a pingo!’ In front of them was a forty-foot high conical hill that looked like the pingos that surround Tuk. Pingos are only found in a permafrost environment, and are the result of frozen ground being forced upward by the pressure of subterranean water. For centuries, the Inuit of the Mackenzie Delta region have used them as navigational aids and lookouts for hunting. Visible from dozens of kilometres away across the tundra, they jut up against the northern horizon like mini volcanoes.

The boys raced toward the pingo.

But it was just another hill, one of many with no end in sight. Worn out, they looked for a place to sleep and found a log that would shield them from the chilly north-west winds. All they had on were T-shirts, shorts and sneakers. The day had been hot, but now they were shivering. They huddled closer to keep warm, and Bernard began to pray, as he did every night before bed at Stringer Hall.

‘Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name,’ he whispered to the skies above. ‘Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.’

Today, the only way to travel between Inuvik and Tuk in the summer months is by plane. In June 2017, forty-five years after Dennis, Jack and Bernard started walking home from residential school, I boarded a nineteen-seat white-and-blue DHC-6 Twin Otter. The 140-kilometre flight would take thirty minutes.

From the air, the hummocky landscape resembled a camouflage pattern: greens and browns of all shades pockmarked with hundreds of lakes and waterways. What from high above appears to be solid grassland is anything but. The permafrost prevents water drainage, and after the spring thaw, the land above it becomes a bog of decomposing vegetation and moss that, like quicksand, can swallow animals as large as caribou. As the plane neared Tuk, trees vanished. Above the Arctic tree line, they are unable to grow in the cold temperatures.

During the winter months, an ice road capable of supporting cars, trucks and skidoos along the frozen Mackenzie River used to connect Inuvik and Tuk. But a month before my arrival, the ice road was closed for good by the Government of the Northwest Territories after decades of service. From the plane I could see occasional glimpses of a new, near-finished road. This was the long-awaited Inuvik–Tuk all-season highway that would open in a few months. It meandered along tiny passages of land between lakes and valleys like a thin pencil line through an impossible maze.

View of the highway from the plane.

In 1959, the Canadian government decided to build a 730-kilometre gravel road from just east of Dawson City, Yukon, to Inuvik. Oil and gas exploration in the region was thriving and a highway across the Arctic Circle was needed to transport equipment and men to and from the drill sites. Construction was challenging and slow, but it felt historic regardless. By 1972, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau had announced the construction of yet another highway between Fort Simpson and Inuvik, after which, he promised, work would begin on the final stretch of a highway that would connect Inuvik to Tuk. Trudeau compared the new roads to the famous routes pioneered by fur traders 150 years earlier. ‘This road has been a dream until now,’ he said.

It remained a dream for a long time. The final piece of the ‘Roads to Resources’, which would connect Inuvik to Tuk, and by extension Canada to the Arctic Ocean, immediately ran into problems. Oil and gas exploration waned, and the project was deemed too expensive and challenging. For half a century, the road remained a dormant hope.

Then, in 2010, Prime Minister Stephen Harper arrived in Tuk for a visit. Leona Aglukkaq, a Conservative MP from Nunavut, advised Tuk’s mayor Mervin Gruben to ask Harper for one thing, and one thing only. Gruben pitched the highway to the Prime Minister, a legacy project that would link the country from coast to coast to coast and reduce the costs of petroleum exploration in the Beaufort Sea. Harper was convinced, and planning for a highway started the same day he flew back to Ottawa. Construction of the $300-million highway finally began in 2014.

Upon landing in Tuk, I rode a cargo van into town. The young man driving the van cautiously navigated the slippery curves in the dirt road. Driving down the town’s main road, Beaufort Road, we passed small wood-frame homes resting only a few metres above the low peninsula that curves into Kugmallit Bay on the Arctic Ocean. In the overcrowded cemetery six-foot tall white crosses, some draped with colourful wreaths, faced the main road.

The next day, I attended the hamlet’s council meeting. The current mayor, Darrel Nasogaluak, and his fellow councillors eagerly discussed the $500,000 beautification project under way for the opening of the highway in November. Workers were coating dozens of buildings in candy-like shades of paint while others tore down derelict ones.

After the meeting, Nasogaluak and his wife, Josephine, invited me to their home. Since he’d become mayor, his job had consisted largely of preparing Tuk for the opening of the new road. Nasogaluak told me that beyond just attracting tourists, he hopes the road will renew interest in oil and gas drilling in the region. At a town hall meeting in Yellowknife in February, Nasogaluak challenged Justin Trudeau’s five-year Arctic drilling ban, telling the PM, ‘We’re at a loss of what we’ll do next.’

For Nasogaluak, the road to Tuk represents more than an all-weather route to their hamlet: it’s a long-awaited path that he and many others in the town of 900 hope will help their community prosper. At 32 per cent, Tuk’s unemployment rate is three times that of the rest of the Northwest Territories, and five times the Canadian average. The coast on which their community rests is slowly disappearing as it erodes into the sea. Some homes have already been relocated. (‘If we don’t move them, they’ll be in the ocean,’ one councillor remarked about a home near the shore.)

In the coming months, the council will begin consulting on the name of the new highway. Mervin Grubens’ family wants the highway named after their recently deceased patriarch, Eddie Gruben. Gruben founded E. Gruben Transport, which was building the highway with Inuvik-based Northwind Industries. He was an influential figure in the Northwest Territories and died a multimillionaire at age ninety-six. Tuk’s airport is named after his son, James Gruben, who died in a collision on the ice road between Inuvik and Tuk in 2001.

But another proposed name acknowledges a different part of Tuk’s history. Many of the town’s elders are residential school survivors. None of them have forgotten that day in June 1972 when three of their classmates ran away. Back when the road was still a dream, those boys attempted to walk it.

Dennis, Jack and Bernard woke up sore from their first night sleeping on the ground. They looked at the sun and guessed it was around noon. They were famished. They picked some cranberries and blackberries, and found an empty pop can that they filled with water from a stream. Away from the strict authority of Stringer Hall, they felt free.

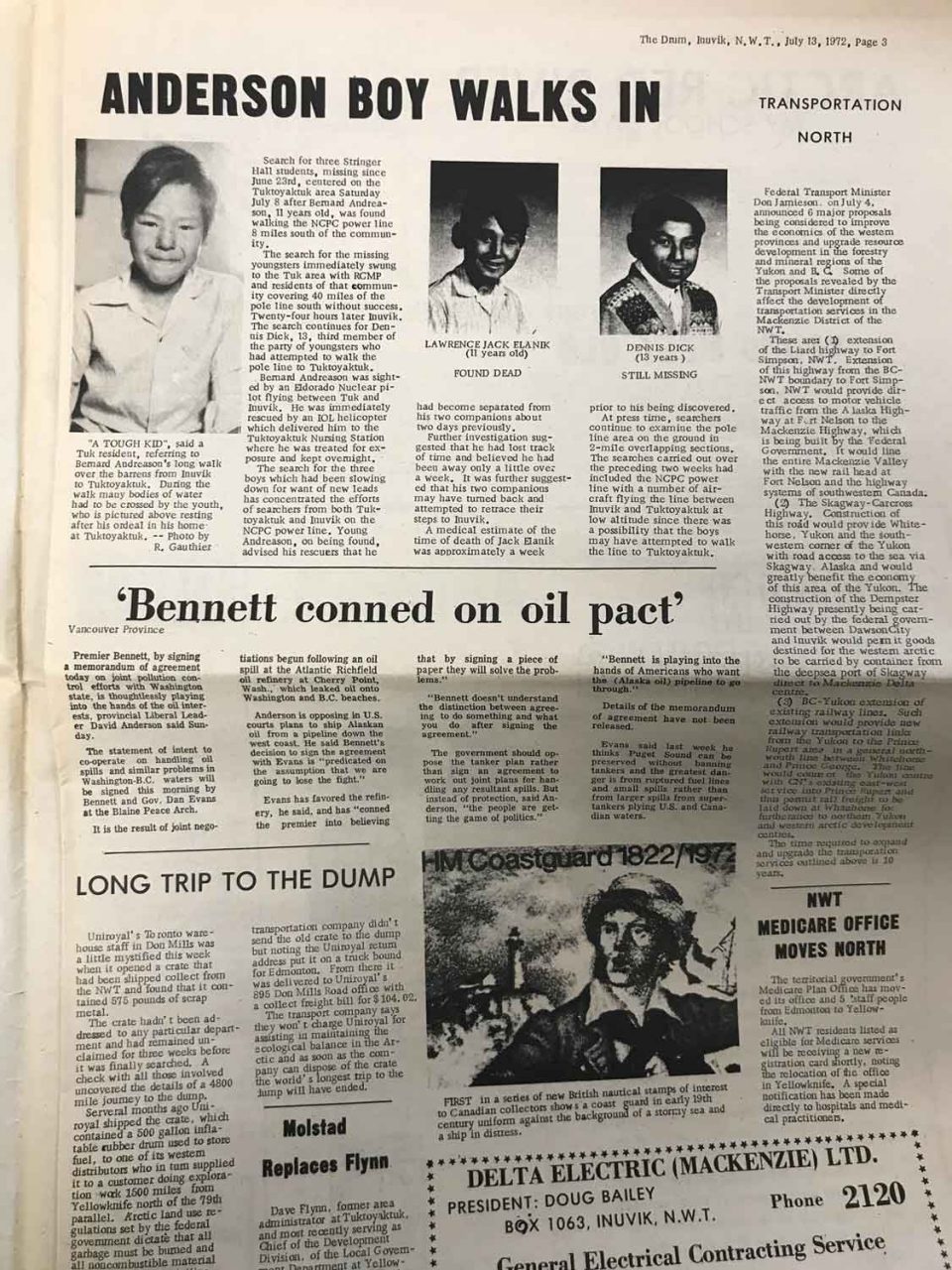

Once the staff at the residential school realized the three boys were missing, they launched a search. This was the fifth runaway attempt of the school year. The previous escapees had all been found. Helicopters scanned the land near Inuvik, and canoes searched the channels and lakes. Students conducted a house-to-house survey in town. No one imagined the boys would try to walk to Tuk.

It was a bright day, and as they walked through some thick bushes, the boys heard a faint chopping sound. From behind a hill, they saw a helicopter speeding across the sky. They made their way to a clearing and waved their hands in the air, yelling as loud as they could. But the chopper flew past them.

The warm weather began to change. Squalls from the north-west brought the temperature down, and rain began to fall. The power lines reached a swift river, and the boys tried to cross it. When the water reached their necks, they got scared and turned back. They were soaked, and every gust of wind felt like a punishing lash. Jack was feeling ill, so they decided to find somewhere to sleep. Jack lay between Dennis and Bernard to keep warm, but he wouldn’t stop crying.

On the third day, the wind was still unrelenting and the sky darker. As they ate berries that morning, Jack begged Dennis and Bernard to return to Inuvik with him. But Dennis objected. Bernard suggested to Jack that if they started walking back to Inuvik, Dennis would get spooked and come running after them.

Jack and Bernard turned back, but Dennis didn’t follow. Bernard couldn’t stop thinking about him. Bernard told Jack to wait for him as he went to find their friend and talk some sense into him. When he reached the river where he’d last seen Dennis, he was gone. Bernard yelled his cousin’s name, but only the wind howled back. He looked for footprints, but there was no trace of him. He returned to Jack and they found some bushes that offered a little cover from the hard rain and slept.

Jack’s crying woke Bernard up the next morning. Jack was too sick to find food. Bernard picked some berries and fetched water in the pop can. Jack had lost a lot of weight. Bernard knew they were in trouble and needed help, but didn’t know if he should continue on to Inuvik, or head for Tuk, where he hoped Dennis might already be.

‘I really want you to come with me,’ Bernard said. But Jack wouldn’t get up. Bernard told him that if he came to Tuk, they could slide down the big hill together in the wintertime, and that he could see the pingos. ‘Dennis might even be there waiting for us,’ Bernard said. But Jack was too weak. ‘Go without me,’ he said. Bernard didn’t want to leave him, but knew if they remained together, they would die together.

Tuk is a town founded by survivors. In 1902, contact with whalers led to a measles epidemic in Kitigaaryuit, an Inuit settlement at the mouth of the East Channel of the Mackenzie River. The dead in Kitigaaryuit outnumbered the living, who now considered the land cursed. A young man, Mangilaluk, went looking for a new place to live. He chose a location thirty kilometres away: Tuktoyaktuk, Inuvialuktun for ‘it looks like a caribou’.

When Mangilaluk arrived at the place that would become Tuk, there was nothing on the peninsula but a few sod houses used for fishing in the summer. But it was an ideal site for a new start for his people, on the edge of a harbour and prime fishing ground for beluga and white fish. He started to build a permanent log house, and before long other families followed.

Mangilaluk served as chief, or Umialiq, for decades. Stories of his bravery, leadership and hunting skill persist today. One story recounts a seal hunting expedition led by Mangilaluk that became marooned on drifting ice floes in the ocean. As the sheet of ice they were stranded on grew smaller, Mangilaluk stoically led his companions to safety by jumping from shifting floe to floe until they reached land.

People believed he was a shaman with the power to shape-shift into a polar bear. In July 1961, two decades after he died, Mangilaluk’s granddaughter, Alice Felix, was eight months pregnant. While home alone one evening, she heard a knock on the door. She wasn’t sure if she was awake or dreaming when the door swung open. A three-metre-tall polar bear stood in the doorway. It walked up to her, put its snowshoe-sized paw on her pregnant belly, and began to speak: ‘If it’s a boy, you name it after me.’

A traditional belief among the Inuit is that human spirits live on after death. After passing, the spirit of the deceased is able to inhabit the body of a newborn should the child receive the spirit’s mortal name, whereupon the child acquires its namesake’s soul and powers. When Alice gave birth to a son two weeks later, she gave him two names. The first was Mangilaluk. The second was Bernard.

Walking towards Tuk by himself, Bernard felt guilty for leaving Jack behind. The weather was getting warmer, but the rains had created an unlimited supply of still water for mosquitoes to spawn in. A black cloud of them hovered around his face. When he reached the river where he’d last seen Dennis, he found a long stick to help him keep his balance as he crossed. The current was strong, but the cool water soothed the mosquito bites that covered his arms and legs. He inched his way across, the water soon covering his chest, and made it to the other side.

The ground was mossy and damp. His feet began to itch in his waterlogged sneakers. He sat on a log and took off his shoes. He desperately scratched his feet, but the itch never went away. Above him, an airplane appeared in the sky. It looked like the same one that had taken him to residential school in Inuvik. It might even be the plane he was supposed to be on to take him home at the end of the school year. He wondered what kind of life awaited him if he made it back to Tuk alive.

At residential school, Bernard had found some consistency in his life. Every night he had a warm bed to sleep in, and there was always food to eat the next day. His life at home in Tuk was less stable. Shortly after he was born, his mother became ill with tuberculosis and spent two years in isolation in an Edmonton hospital. Different families looked after him until David and Bessie Andreason finally adopted him. A family of means, with one of the biggest dog teams in town, they had adopted other children as well. The record player was always on in their prefabricated house, and Bessie, who loved to dance, would pick Bernard up and teach him how to waltz, his small feet resting on hers.

Then, when Bernard was six, David became sick after eating badly prepared beluga. After he died, Bessie began drinking heavily and gambling. The record player stopped spinning, and they never waltzed around the living room again. On weekends, adults would pour into their home to play bingo and blackjack and drink the home brew that Bessie concocted in their bathtub with molasses and yeast. Its sweet aroma filled the house while it cured.

Soon, Bessie started seeing a new man who didn’t want Bernard around anymore. Bernard began moving from house to house again, staying with different friends and relatives, and often sleeping outside. In the winter he would steal clothes and blankets to build small nests underneath houses where he could sleep. The nice clothes David and Bessie bought him from the Hudson’s Bay Company no longer fit him, and his unkempt appearance drew the attention of his principal at the Mangilaluk School. In 1969, the principal decided it would be better for Bernard to attend residential school than stay uncared for in Tuk.

Residential schools had existed in Canada since 1831, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that a significant number of them operated in the north. These government-sponsored religious schools were established to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture by ripping them away from their families and communities. When Western European colonization and evangelization finally arrived in the Arctic, what had been a relatively unscathed Inuit culture began to change rapidly. Bernard’s biological parents had been part of the first generation of Inuit that passed through these schools. It was in such an institution that they first met and fell in love.

Before 1955, fewer than 15 per cent of school-aged Inuit were enrolled in residential schools. Most children still lived on the land with their families, learning traditional skills and knowledge. Rather than teaching students how to hunt, skin game, and build igloos and kayaks, residential schools taught a curriculum used for white children in Alberta.

By 1964, more than 75 per cent of Inuit children attended residential schools. Their values, language and customs were supplanted overnight by a culture that saw itself as benevolent and superior, and saw the Inuit as primitive beings in need of sophistication. The young Inuit who went through the residential school system experienced an assault on their traditional identities that had shattering consequences: they are often referred to as the ‘lost generation’.

On his initial flight to Inuvik and Stringer Hall, Bernard couldn’t wait to see his cousin Dennis. When he arrived at the school, he stared at in awe. He’d never seen a two-storey building before. The school was split along religious lines. Anglican students stayed in Stringer Hall, and Catholic students in Grollier Hall. The identical dormitories, which rested on piles driven deep into the permafrost, were each meant to house 250 students, though they were often crammed with more. Anglicans were taught to hate Catholics, and Catholics to hate Anglicans. Each had their own playground.

Leonard Holman, a stout reverend with a thick grey moustache, gave Bernard the number his supervisors would know him by from then on: 356. His long black hair was shorn and replaced with a buzz cut. He took his first shower and then Holman showed him to his bed in A dorm. ‘You’re gonna be okay here,’ he said.

Next door at Grollier Hall, things were not okay. Across the hall from the senior boys dormitory lived Paul Leroux, a young dorm supervisor from Granby, Quebec. He was involved in all manner of school life, from coaching soccer to taking photographs for the school yearbook. Some nights, he would invite boys into his room, where he gave them alcohol and showed them pornography. Once they were drunk, he encouraged them to perform sexual acts on each other, and then on him.

Leroux was one of four staff members to use Grollier Hall as a hunting ground for young boys. Over a span of twenty years, these four men would molest dozens of children and youth, spurring a cycle of abuse that would spread like a malignant cancer across the entire school, and follow many of the children back to their home communities.

The year before Bernard ran away from Stringer Hall, he too was drawn into this tempest of sexual violence. The older brother of a friend, a senior boy in Grollier Hall, molested Bernard.

A week had passed since Bernard left Inuvik, but he was losing track of time. When the sun doesn’t set, it can feel as though time has stopped altogether. Its warmth felt good on his skin, but the heat brought the mosquitoes back. There was little skin left now for them to puncture. He was losing a lot of weight, and his pants kept sagging lower and lower on his diminishing frame.

Up ahead, Bernard saw a seismic line – a gash in the tundra that extended for many kilometres, made to collect data that would help decipher the make-up of the earth below. Two years earlier, Imperial Oil had discovered oil eighty kilometres northeast of Tuk at Atkinson Point. Other companies were now drilling thousands of feet into the permafrost all across the western Arctic, hoping to make similar finds. Had he started his walk a few months earlier, Bernard might have run into one of the large crews of oilmen. But during the short Arctic summer, when the top twelve inches of the tundra becomes a mushy swamp, oil exploration is shut down.

Still, the seismic lines were evidence of people. Bernard decided to follow it. He was sure it would get him home, or at least to someone who could help. When he looked behind him, he could see the power lines heading in a different direction. Until now, they had been his only compass. From far away Bernard thought they looked like toothpicks sticking out of the tundra.

The Inuit tell stories of creatures called Ijiraat, elusive land spirits that can transform into any arctic animal, or even into humans. They lie in wait for lone travellers, changing shape to trick them, so they can get close. They create mirages: when they are near, mountains or hills far in the distance appear to be much closer. After an encounter with Ijiraat, travellers experience memory loss and become disorientated.

Malnourished and exhausted from the dozens of kilometres he had already travelled, Bernard began hallucinating. He could no longer tell if he was awake or dreaming. He questioned whether he was still even alive. Sometimes when he was walking in this state, he could hear people ahead of him telling him to ‘hurry up’.

He couldn’t see the power lines anymore. He began to worry that the seismic line was leading him astray. He saw a pile of small bird bones. The thought that he too could end up an anonymous stack of bones on the land terrified him. For the first time since leaving Inuvik, he started to cry. He thought about Dennis and Jack, whom he had not seen for many days. He could hear Dennis’s voice in his head, reminding him to follow the power lines. He turned back to find them.

That night, he cried himself to sleep and had a nightmare. Large groups of people were walking from Tuk to Inuvik along an invisible highway. Bernard was trying to catch up with them. He stopped a woman and asked if his mom, Bessie, was okay. ‘She’s okay,’ she replied. ‘She’s waiting for you.’ Then he saw two boys he knew from Stringer Hall. They ran around him in circles, taunting him. Bernard chased after them. They jumped behind a mound of mud, and when Bernard reached it they had disappeared. When he woke up he found himself next to that same pile of mud, but nobody was there.

He made it back to the power lines and continued following them. Then he’d hear voices calling out to him, but before he could reach them, he’d realize he had strayed from the lines. Then he saw two women he recognized from Tuk. He pumped his tired legs as fast as he could, yelling as he ran, his heart pounding through his chest. They raised their heads and looked at him in puzzlement. They were reindeer.

Ahead of him, Bernard could hear a river. It was much bigger than the previous one, ninety-feet wide with thundering rapids. He started to cross, making an effort to be careful, but he lost his footing. He struggled against the current, trying to swim back to shore. He felt too weak to go on. If he allowed the river to swallow him, it would be over. He wouldn’t need to fight anymore.

News had spread around Tuk that a journalist ‘from south’ was visiting and writing about the three boys that attempted to walk from Inuvik to Tuk. Strangers began approaching me, offering me details of the story as they remembered it. Everyone seemed to have heard a version.

Outside the Northern Store, one of Tuk’s two stores, I met Gerry Kisoun, a member of the search team that looked for the boys. He remembers the gloom that fell over town when Jack Elanik was discovered. He had been dead a week before his body was found, crawling with maggots and insects.

On 21 June, I attended Tuk’s celebration for National Aboriginal Day. Dozens of families gathered by an outdoor stage where they ate caribou meat and drank tea that brewed on an open fire. A band played folk music, and a few adults and children jigged on the wooden stage. As I sat on a bench speaking with a few elders, a woman named Marjorie who had attended Stringer Hall approached me and said that I should go and visit St John’s Anglican Church in the old part of town and look for a Bible.

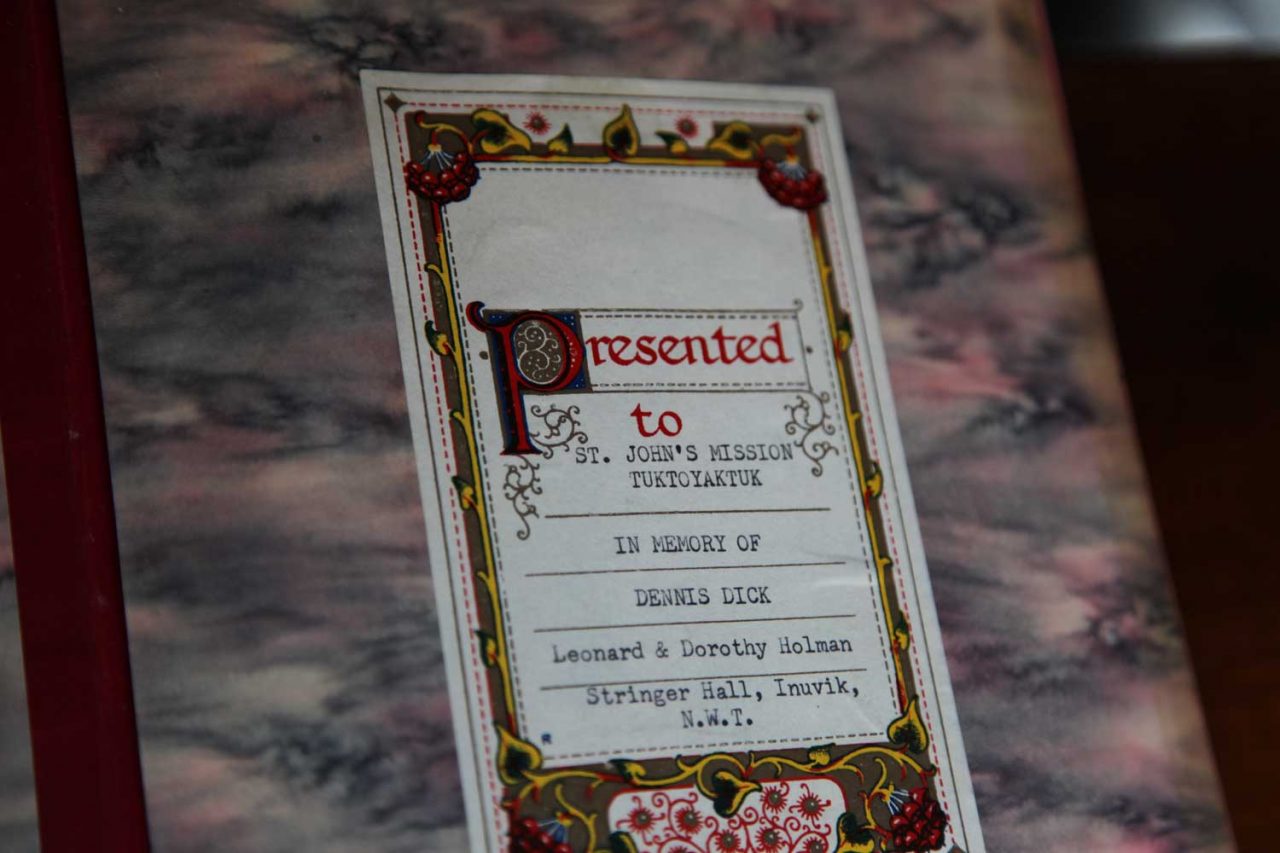

The Bible dedicated to Dennis Dick in St John’s Anglican Church, Tuktoyaktuk, where it rests on the pulpit.

The old log church stood facing the bay. The door groaned loudly as I pushed it open. Inside was dark and musty. There were no longer any clergy tending to it. Church attendance in Tuk had waned in the years since the residential schools had been shut down. I passed by rows of empty benches on my way to the pulpit, then I opened the dusty maroon-coloured bible that sat on it. On the first page was a dedication. ‘Presented to St John’s Mission Tuktoyaktuk,’ it read. ‘In memory of Dennis Dick.’

A couple days later, I visited Jasper Andreason, the biological brother of Dennis, and adopted brother of Bernard. Like Bernard, he was adopted by Bessie and David Andreason as a boy. Jasper has never forgotten his little brother Dennis. For years after his disappearance, every summer him and his biological mother, Margaret, went looking for him along the power lines. ‘We figured he might have drowned, or a bear might have got him,’ Jasper said.

Of his eight biological siblings, Jasper is one of the few to have survived into old age. His sister Millie overdosed in a hotel on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Ruth ran into oncoming traffic and was killed in Edmonton. His brother Albert, an intravenous drug user living in Toronto, was diagnosed with Aids. When he became sick with pneumonia, he hanged himself. ‘They all came home in caskets,’ Jasper told me.

The current pulled Bernard downstream. He had no energy left. Nearly two weeks had passed since he left Inuvik, and he had used every bit of his strength to get this far. He kicked his feet and swung his arms to get back to the shore.

But he still had to cross this river. He climbed a hill to get a better view and saw a spot where he could safely cross. He traversed there and then came to two big lakes. Going around them would take too long, so he waded between them. The water was shallow, and he could see small fish darting between his legs. After passing through the lakes, he was exhausted. He found a small hole to sleep in – it was a perfect fit for his emaciated body.

A view of the pingos, with Tuktoyaktuk seen in the distance. The pingos shown are some of approximately 1,350 pingos surrounding Tuktoyaktuk.

The next morning, a loud whirring noise woke him up. He thought he was dreaming, but he could feel vibrations in the ground where he had been sleeping. He climbed out of the hole, and saw a helicopter getting ready to take off. He ran towards it, but it was too late. It was climbing higher and higher into the sky.

Bernard was near Kitigaaryuit, the cursed land his great-grandfather and namesake Mangilaluk had left behind. Seventy years earlier, hundreds of his ancestors had perished here. Now, as Bernard crossed the landscape in which his descendants were buried, he felt his own death was near.

After walking for another hour, starving and barely able to keep his head up, he reached the top of a small hill. A sudden jolt brought life back into his weakened body: in the distance, he could see the pingos. This time they were unmistakable. He fell to the ground and started crying. Tears streamed down his face as he began to walk the last ten kilometres home. Fourteen days had passed since he left Inuvik.

A few days later, and a couple weeks before his twelfth birthday, Bernard was recovering in Inuvik General Hospital. He had lost nearly thirty pounds, and his shoes had to be cut off with scissors because his feet were so badly swollen. He was suffering from trench foot, an ailment caused by sustained exposure of the feet to damp and unsanitary conditions.

After Bernard was found, fifteen men in Inuvik and twelve in Tuk searched along the power lines for Dennis and Jack. Some walked for over sixteen hours, but they recovered only one body: Jack’s.

Bernard’s biological family took him back in. They asked him what happened during those days he walked between Inuvik and Tuk, but he never said a word. He was consumed with guilt that he’d survived when his friends hadn’t. ‘We were so happy he was alive, so we just let it go,’ Bernard’s older brother Jasper later told me. ‘We couldn’t get him to talk about it, and nobody asked.’

Page 3 of Inuvik newspaper the Drum, 13 July 1972.

Bernard wasn’t allowed back at residential school after he ran away, so he stayed in Tuk, occasionally attending the Mangilaluk School. After years with the Andreasons, and then at residential school, it was tough to readjust to life with his biological family. For years, he couldn’t bring himself to call his biological father ‘Dad’.

Bernard’s parents, Alice and Joseph Felix, started drinking more frequently while Bernard had been gone at school. Now that he was back his mother beat him often. Life at home became unbearable. He tried running away, but in a town cut off from the world, there was nowhere to run to.

Every year suicides increased in Tuk, and Bernard watched as fellow classmates from residential school were buried in the cemetery. Between September 1982 and October 1983, there were fifteen suicides, most of them boys and young men. Bernard’s own sister attempted suicide. It was a wake-up call for his parents. They stopped drinking, but life never got much easier.

After Imperial Oil’s 1970 discovery, a sudden windfall of money poured into Tuk. Young people left school to work temporary jobs in the oil industry. Tuk was a dry town, but bootleggers brought in an unlimited supply of alcohol they sold at four to five times what it cost in a store. They chartered aircraft stocked with cases of booze that landed on lakes where they were met by trucks or skidoos. The surge in drinking led to an increase in theft and violent crime.

Tuk’s two social workers couldn’t keep up with the volume of work, which increased whenever the oil industry shut down for the season and people were left unemployed. The three largest oil companies in the region, Dome Petroleum, Esso Resources and Gulf Canada, were now offering alcohol and money counseling to their workers. But Tuk’s own alcohol and drug abuse centre was forced to close its doors after its power bills went unpaid.

Bernard’s older siblings knew there was something different about him. They beat him, trying to ‘toughen him up’ and ‘make a man of him’. As he grew older, people in town began questioning him: ‘Why aren’t you married? Why aren’t you with a girl?’ Men in Tuk were expected to be hunters and trappers, and to have lots of kids. Bernard tried having relationships with women, but he could no longer hide who he was. One night a group of friends came into the house looking to party. Instead, they found Bernard and another man in bed.

Bernard began to drink to escape the depression and remoteness he felt as a gay man in the north. He drank to forget the physical abuse he suffered at the hands of his mother and older siblings, and he drank to forget the sexual abuse he endured as an 11-year-old at residential school. Most of the time the drinking only made him numb. But sometimes it made him angry.

At 2 a.m. on 4 June 1982, while it was still light outside, Bernard entered the home of his next-door neighbours. Richard and Winnie were in bed sleeping. Bernard picked up their still-full coffee pot and smashed it on a wooden table, staining the carpet with coffee. Then he picked up their TV and threw it hard against the ground. Richard woke up and got out of bed to see what was going on. When he saw the mess Bernard was making, he told him to get out. Bernard closed his fist tightly and punched Richard above his right eye.

Richard fell to the ground, knocked out from the blow. Bernard lifted his boot and kicked him twice in the head. Then he found a log near the fireplace, picked it up and cracked it over Richard’s skull. While blood from the deep lacerations on Richard’s head spilled onto the carpet, Bernard tipped a washing machine over onto his still body. Then he went into the bedroom, where Winnie was still asleep. Bernard began punching her in the face.

The next day Bernard woke up in jail without any memory of the previous night. He was twenty-one years old and facing five years in prison for assault. During the trial a year later, his lawyer argued that Bernard was trying to turn his life around. He’d attended rehab and was working on an article for a newspaper in Fort Smith.

‘I think that anyone who gets drunk and goes into an older couple’s house and beats them brutally as you did can expect to go to jail for a longer time, a much, much longer time,’ the judge said during his sentencing. ‘So you are very fortunate.’ Bernard got off easy: four months in prison at South Mackenzie Correctional Centre and two years’ probation.

Bernard’s fellow inmates tormented him when they learned he was gay. It was there in prison that he decided he could never live safely in the north as a gay man. He began planning his next escape.

When he left prison, Bernard came back to Tuk and learned that his stepmom Bessie was ill. Years of excessive drinking had taken a toll on her. As she lay in a bed in the nursing station, Bernard called a minister to come and pray for her. The minister denied his request. Bessie was a drinker and a gambler, he said, and he wouldn’t be praying for her. Instead, Bernard held her in his arms and prayed to a God that he hardly believed in anymore.

After Bessie died, Bernard’s determination to leave Tuk was solidified. He saw a newspaper ad about an Indigenous journalism program at Western University in London, Ontario. If he could write, he could share his story, and explain why he so desperately needed to leave Tuk. He booked his flights, packed his bags and planned never to return.

One evening in Tuk, I met with Bernard’s younger brother, Stanley. He and his wife picked me up in their silver truck and parked the car near a bench with a view of the bay. It was late at night, but the sun still shone like it was midday.

Stanley feels like he was spared, because he never attended residential school. But that didn’t matter much. When his friends returned from school in Inuvik, they brought the problems of residential school with them. ‘They came back with a whole shitload of different ideas and attitudes about how life should be lived,’ Stanley told me. Within the hierarchical society of residential school, kids learned to draw lines between themselves and others. It was Catholics vs Anglicans, abusers vs the weak, and any dispute was resolved with violence. ‘Years ago,’ he said, ‘survivors started talking about sexual abuse, and they came back with that, too.’

In 1996, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police received a complaint from a former student at Grollier Hall who said a staff member sexually abused him. Mounties interviewed more than 400 former students of the school. Eight months into the inquiry, police had collected enough evidence to convince a judge to issue a search warrant for an apartment in Vancouver. It belonged to Paul Leroux.

The interviews with the students, now grown men, also produced evidence against two other former school employees, Joseph Jean-Louis Comeau and Jerzy George Maczynski. They all pled guilty. (A fourth school employee, Martin Houston, was charged and convicted in 1962 for the sexual abuse of five boys at Grollier Hall.) During Leroux’s trial in Inuvik he was fitted with a bulletproof vest. No one tried to kill him, but four of his former victims committed suicide during the trial.

An RCMP report revealed that sixty-one former residents of the school from the 60s and 70s had since died. Sixteen committed suicide, five died as a result of acts of violence, and three froze to death after heavy drinking. Fourteen died of natural or unknown causes. In 2002, the federal and territorial governments, along with the Roman Catholic Diocese of Mackenzie–Fort Smith, reached a historic out-of-court settlement with twenty-eight of twenty-nine Grollier Hall victims.

‘A lot of people had secrets,’ Stanley told me as we stood by the bench overlooking the sea. He told me he understood why Bernard had to leave. He remembered a few nights before Bernard left, how badly he wanted to stay. ‘I think he was more afraid to stay and live the way he was than he was afraid of leaving.’

In 1993, Bernard sat in a doctor’s office in London, Ontario, to have his blood drawn. He was thirty-two, and had been in and out of treatment centres for alcoholism. The current rehab centre he was in required blood to test for hepatitis and other diseases.

When Bernard came in for his results, the doctor wouldn’t come near him. ‘I have some good news and some bad news,’ the doctor said, standing five feet away. ‘What would you like to hear first?’ Bernard asked for the bad news first. ‘The bad news is you’re HIV positive.’

‘What’s that?’ he asked. The doctor told him it was a virus that was going to develop into Aids. ‘How long do I have to live?’ Bernard asked.

‘The good news is: if you take care of yourself, and that’s a big if,’ the doctor said, ‘you might be able to live another ten years.’ For the second time, Bernard felt his life being cut short. He didn’t want to die.

After the diagnosis, Bernard was afraid to go near anyone. He stopped shaking people’s hands and sat as far away from others as possible. He began to isolate himself. He couldn’t talk to anyone about his disease except when he was drunk, which happened more and more frequently

When Bernard switched on the TV, he saw stories about Aids on the news. In cities like New York and San Francisco, they were calling it ‘gay cancer’. He saw Dr Peter Jepson-Young, a young Vancouver doctor, speaking about his own experience with Aids on TV. In Vancouver, there were more options for treatment, so he cashed his welfare check to buy a bus ticket. He had a single plastic bag of clothes, and relied on strangers to buy him a sandwich or a coffee during that four-day bus ride west.

Bernard’s bus arrived on the Downtown Eastside, at the time considered Canada’s poorest neighbourhood. An HIV/Aids epidemic affecting thousands was prompting a public outcry. Doctors in the city were diagnosing two new HIV cases every day, and by 1997, approximately one person was dying daily.

Bernard’s weight started dropping, and he was tired a lot of the time. If he caught a cold, or felt a scratch or lump in his throat, he wondered if that was how he would die. He was scared to sleep because he thought he might not wake up the next day.

A cross draped in a wreath of flowers in Tuktoyaktuk’s cemetery.

In the first weeks of January 1999, CBC Radio in the Western Arctic announced upcoming community consultations in the Inuvik region. James Simon, a researcher hired by the territorial government, would be travelling to five communities, holding information sessions and interviewing residents about the planned Inuvik–Tuk highway. Hopes were high that finally some progress might be made on building the road.

Simon conducted dozens of interviews and heard concerns about children losing their culture and picking up ‘bad habits’ from the south: the highway would make it easier for drugs and alcohol to enter the community. Despite these worries, most people overwhelmingly supported the road. They all said it would be a blessing for Tuk, whose people had long been isolated from the world underneath.

Tuk was Simon’s final stop. More than a hundred residents showed up at Kitti Hall to share their thoughts about the highway they had been waiting to be built for forty years. They told Simon how the closing of the ice road every summer led to increased depression. They hoped that the all-weather road would bring more jobs to town.

Towards the end of the meeting, Simon’s Inuvialuktun translator, Agnes White, introduced him to an elder who said she had something important to tell him. Her name was Alice Felix. She told Simon a story that elders across the Mackenzie Delta region had told him a dozen times during his trip. Alice said that in 1972, her eleven-year-old son, along with two of his friends, ran away from their residential school in Inuvik and attempted to walk to Tuk.

The story of her son’s mystifying survival had spread across the Western Arctic. Tuk’s mayor at the time, Emmanuel Felix, held a meeting with several other town elders after Bernard was found. They decided that should a highway ever be completed between Inuvik and Tuk, it should be named after the surviving boy.

With the promise of the highway revived once again, Alice told Simon she hoped the road might still be named after her son – using his Inuvialuit name, she said, the name of his great-grandfather and the founder of Tuk: Mangilaluk.

Since construction of the highway began in 2014, the story of the three boys has resurfaced. For the people of Tuk, naming the highway after Bernard was to acknowledge their own resiliency. Through colonization, epidemics brought by whalers and the horrors of residential schools they persisted. Even as the peninsula they had lived on for one hundred years eroded into the sea, Tuk survived.

In August 2016, a year before the road would be finished, Alice Felix died. Towards the end of her life she suffered from dementia. She sometimes spoke about polar bears. They were coming to visit her, she’d say. She was buried in Tuk near the grave of her grandfather, Mangilaluk. Bernard didn’t make it to her funeral. It had been a long time since he’d been home.

In the mid-90s in Vancouver, Bernard began hearing about First Nations support groups for those with HIV and Aids. He started to meet other young Indigenous men and women in similar circumstances. Some were gay, and had been kicked out of their homes. Others were drug users who felt they couldn’t return to families and communities that were afraid to hug them or share the same cup. Many of his new friends died within a year of being diagnosed.

Through the support groups he attended, Bernard met Carole Murphy, a doctor who specialized in HIV treatment. By 1995, doctors were experimenting with the Aids Cocktail, an antiretroviral therapy. Bernard was a perfect candidate for this new treatment. His appetite slowly came back. His viral loads decreased, and his CD4 and T-cell counts increased. When he hopped on the scale, his weight read 165: the weight before his diagnosis.

He moved to Prince George, where he started taking university courses. He helped form a group called the Frontline Warriors. Working with an organization called Positive Living North, which provides support, awareness education and prevention services to people living with Aids, Bernard and his fellow warriors went to the front lines. By 2000, as many as one in four new HIV/Aids infections in Canada was among Indigenous people. Within this community there was poor access to testing and widespread discrimination on reserves against those infected. Bernard was concerned about how the younger generation of Indigenous men and women with HIV would fare. He began sharing his story on reserves and in high schools.

‘When I found out that I had tested positive for HIV, at first I was in denial. That was in 1993,’ he would begin his speeches. ‘My doctor told me I had about ten years to live. But I’m still here. I survived.’

By 2008, Bernard, along with 80,000 other residential school survivors across Canada, began detailing their experiences in court-ordered private hearings to receive compensation. The more abuse an individual was subjected to, the more compensation they’d receive from the federal government. Bernard was too scared to tell a stranger about the sexual abuse he had suffered as a child, and withheld this information. For this reason, he received a smaller settlement. His suffering was deemed to be worth $40,000.

As part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission was launched to document and preserve the experiences of survivors. Bernard attended a gathering in northern B.C. where he listened to elders who had never talked about their time in residential schools finally open up decades later. Bernard decided to share his story as well. While he spoke, he thought about all those who would never speak: children like Dennis and Jack who never made it home, and the classmates he lost to suicide and drug and alcohol abuse.

After sharing his experience, Bernard went outside and lit a cigarette. A First Nations spiritual leader who had been in the room approached him. ‘There were so many people behind you,’ she said. ‘Who?’ Bernard asked. ‘They came down from the heavens,’ she said, ‘you spoke for so many people.’

Bernard, August 2017

In August 2017, I met Bernard outside the Dr Peter Centre, a 30,000-square-foot health-care facility that specializes in care for people living with HIV/Aids. It’s named after Dr Peter Jepson-Young, the young Vancouver physician diagnosed with Aids who Bernard saw on television when he himself was first diagnosed.

After spending a decade living in Prince George, Bernard missed life in Vancouver, the city he credits with saving his life. It was here, at the Dr Peter Centre, that he found a community after being diagnosed with HIV. We were meeting a few weeks after Bernard’s fifty-sixth birthday. His birthday comes two weeks after the day he survived the journey from Inuvik to Tuk, and since he turned twelve, it has always been a reminder of the years he has lived since then, and of the years that were taken from Dennis and Jack.

As we walked through the halls of the Dr Peter Centre, Bernard spotted a hanging quilt, imprinted with his photograph and those of other members of the centre. It was made fifteen years ago, at a time in Bernard’s life where he said he had had ‘enough of this dying crap’. In the photo he is smiling boyishly, crinkling his eyes. Not all the individuals with their photos on the quilt have lived as long as Bernard.

The phrase ‘long-term survivor’ refers to people who have been living with HIV since before the life-saving Aids Cocktail turned HIV into a manageable illness rather than a death sentence. Being a long-term survivor of HIV is associated with survivor’s guilt: the mental trauma that occurs when a person believes he or she has done something wrong by surviving an event that others did not. Bernard, a long-term survivor, has witnessed countless friends lose their lives to AIDS.

He often asks himself, ‘Why me? Why did I survive?’ It was the same question he asked himself as an eleven-year-old boy when he made it back to Tuk. Not a day of his life has gone by that Bernard has not thought about the two weeks he spent walking between Inuvik and Tuk. That journey is etched into his memory, and his dreams, where he still sees Dennis and Jack. The chronic guilt of survival has followed Bernard for forty-five years.

In Tuk, many people have already started unofficially calling the road between Inuvik and Tuk ‘Bernard’s Highway’. When the highway finally opens, Bernard wants to go back for his first visit in many years. He hopes to drive along the highway above the permafrost through the lakes and valleys he walked so long ago. When he sees the pingos in the distance, he will know that he is home.

An abridged version of this story was featured in the print edition of Granta 141: Canada.

This story was completed at the Banff Centre’s literary journalism residency, with the editorial support of Tim Falconer. The author would also like to thank Aluki Kotierk, who provided valuable feedback in its later stages.

Unless otherwise stated, all in-text photographs courtesy of the author.

Photograph of Stringer Hall courtesy of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada Archives.

Feature photograph courtesy of NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Shot shows a portion of the Mackenzie River Delta.