On the Underground I feel safe and warm. A poster for everyone. Then I feel sick of it all and have to get out for fresh air. I start walking down the Old Brompton Road. A favourite for the gay ones. Everyone looks deliciously dressed. Now I feel hungry and would like some bread and oxo or something. (I wonder if man can restore God back to his old Love, omnipotence? Jean Cocteau had Orpheus; Walt Whitman had himself. One might as well let people work things out for themselves.)

‘Sorry.’ Why don’t people look where I’m going? Walking into me like that. I think I’ll make my way back to town and spend the night in a coffee bar listening to the juke-box.

Tottenham Court Road. I stand looking at nothing, doing nothing, which is an education in itself. But too many people and the neon lights cause useless thoughts and unconscious problems in endless negative patterns and I am a slave to this sick nonsense so say to myself: ‘Sit down, jump up or go for a run.’ No good. I haven’t got that kind of energy, and walking down the road stop at a theatre where the words tragic hands are written up in large black letters and who’s who in it. I am not brave enough to go in by myself. Theatres are too personal and heartbreaking. Across the road is a cinema, so I wait to buy a ticket and there’s a bloke and his girl kissing like mad. Trying to find a seat, I fall over everyone’s feet. One arm of the seat is missing; the man next to me has the other. I’ve walked in halfway through the performance. A Japanese film about the Crucifixion, Mary in a nightie. Dialogue:

‘I beg that you love me.’

‘I will forgive you.’

‘Go in peace and not in folds.’ etc. etc.

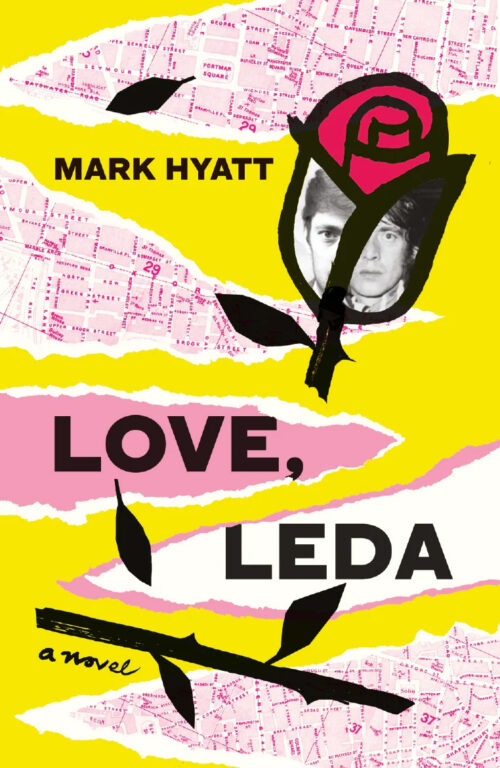

I fix my feet on the seat in front of me and fall asleep. Two hours have passed. I look at the adverts and laugh. Get up and go. Outside the night is like a bad dream, black as Buddha and thousands of headlights. Something to live with. Two thirteen-year-old boys stand in a doorway smoking, happy to Love, Love, Leda be up and about. I have to look because their skin is so pure and their clothes in such bad taste. They try to imitate gentlemen and finish up the miniature of their fathers. As I pass I have another look and out goes one tough tongue. I stand in the exit of the Underground to keep warm and let time pass in thought. Lovers rush down the tube on their way home. They look depressed, and I feel that this is what the Underground does to them; kills the whole evening. I move away self-contained and placid. Not even my own reflection could make me happy right now. But I mustn’t discuss myself with myself because it leaves me with no duty towards living. I venture down Museum Street. cadets beat – a jazz club. I pay ten shillings entrance fee and make my way down tiny stairs into a three-room basement. Somewhere to stay until morning at any rate. A place for the arty types, all with beards and looking very similar. The girls wear jeans, grow their hair to their waists and have breasts like mounted plates. The older ones sit on the floor and watch the youth of today dancing. I am without an address so I sit on the floor out of sheer tiredness and join them (the learned ones). Next to me is a woman with mink eyelashes and too many lines on her face to be alive. She turns to me.

‘I am an existentialist. What are you?’ she asks, to please herself.

‘God.’

Her past experiences tell her to buzz off. She jumps up and starts dancing with a man of similar origins to herself. I push myself into a corner, a remote and humble place, and employ my eyes in self-deception. It’s terrible to be young, always randy; one needs material. My approach to other people is bad because of my awareness of their needs. I leave myself misunderstood every time. Everything inside me is too factual.

A young lad stands over me, his legs like fire.

‘Can I sit beside you?’

‘Please do.’ He sits on my hand which is a good start. I look at his ear.

‘Stop looking at me like that. I’m not a homosexual,’ he says.

Inwardly, I observe that I’m not suffering from leprosy; anyway, eyes were made for looking and as we’re not permitted to touch everything we fancy, we have to make do with sight alone.

He puts his hand inside his coat pocket and pulls out a book of contemporary verse, brushes through the pages and points at a poem, which he reads:

When the rose is dead

Is it not said

That love will have to wait.

He closes the book and puts it back into his pocket, then grins dreadfully. I get up (as if it were my cue) and walk over to the counter. I buy a small bottle of gassy orange drink for half a crown. Jazz is an epitaph for the living. I should have been an angel for I hate being stationary. As I walk back someone stands on my toe. I limp into the corner and slide down the wall. The young man is dancing with the woman who spoke to me earlier. The clock on the wall has no hands, but painted on it are the words sorry no tick, which is candid. I aspire to nothing because I exist, and the study of religion is like the study of the dreams I never had. I feel like a thousand gods, but not even a thousand gods could weep the way I do. This silent fear in my body will evoke the child ego still secure at some point in my mind and repress everything I have.

The band discovers it needs a break and judging by the looks of the other people, which give the impression of expressionless virgins on heat, they need a rest too. The brilliant lights down here are not wanted and the big butterflies painted bright yellow are a little out of place, a poor idea of getting back to nature. This matter on my lungs is getting out of hand. I must beat my chest to keep my body in order and it stings.

‘Are you OK?’ asks a cuckoo of a man who sits down beside me.

‘I feel a little amber inside but I’ll be all right.’

‘Do you want to buy any Nembutal or Ephedrine, cheap?’ he says as he looks round for a woman.

‘No thanks. I’ve given up religion.’ He looks surprised.

‘What’s a pretty fellow like you doing down here anyway?’ he asks.

‘I’m homeless.’

‘I’ve got some records at home. Would you like to come back and listen and I can let you have a bed for the night?’ he says, with smiling eyes. I look him over and he just isn’t me.

‘What kind of music do you go in for?’

‘Tchaikovsky, Liszt, you name it, I’ve got it,’ he says, unsure of himself. I couldn’t go to bed with him if he paid me.

‘No thanks, I’ll stick it out here until morning.’

He gets up and sits down in the corner facing me; the kind of man that imagining he might have a mild touch of VD, goes and tells some sympathetic girl friend for the sake of being with it. Now his stare is making me feel uncomfortable. I wish he could lose himself. A girl sits down beside me. She is built like Eve. The band starts up.

‘Great, great; isn’t it great?’ she remarks very quickly. ‘I come from Hampstead. Jazz moves me.’

She continues. ‘My name is Rosy. I’m a violinist with the London Philharmonic Orchestra. I love it down here. What’s your name?’

‘Leda.’

‘Oh, I must go. There’s my boyfriend waving to me. I’ve been hiding from him. Bye, see you around some time.’ And off she goes like a fairy, leaving me a card which I slip into my pocket.

Cuckoo is still staring at me. I reach out and pick up a newspaper. I read:

Peter Wood, 619 Bayswater Road, W.11. [He is a dear friend of mine] was found dead in his flat, late last night. Sir William Boggs of Scotland Yard, investigating, finds nothing to suspect murder and believes that Peter Wood committed suicide of his own free will. The inquest will be two weeks from today.

Tears of farewell begin to flow down my face. (He cried in a city of dreams, where love is everlasting but hope forgotten.) I tear the paper in half, spring up suddenly and make a bitter exit. Outside, the early morning is without grace. I know it to be only the emotions of the moment but I feel I must give some service to our old friendship. I rush in and out of the cars in the Strand, trying to make up for a friendship I had forgotten which is eating me.

At Oxford Circus tube station I stop to think and take the Underground to Chalk Farm. At least there is Thomas who lives in Cambridge Square. I walk down the steps into the basement and sit on the doorstep, crying in silence. Time passes and I get frozen stiff. Thomas must have got up some time ago. I can hear him moving about, getting ready for work. The door opens and I look him straight in the eyes. He sees I am upset and stands back to let me through.

‘I’m going to work. Make yourself at home, but close the door if you go out,’ he says quietly, and closes the door on himself.

I smell fresh coffee and walk into the kitchen. I put the gas on, standing close to the stove to get warm and make a new pot of coffee. I add a lot of sugar to my cup. Thomas has lived by himself for years. His flat is pure blue. He suffers from loneliness and is a very sad person, gentle as a bird. Always dressed in black. (A kind of peaceful madness with him.) I like him a lot. He only has a dozen friends, if that, but plenty of books to make up for it. I have a bath and put on clean clothes, dance around the flat, taking care not to upset or break anything. I find some drawings of his, also ‘Fanny Hill’ on record. He makes a point of his brain and often gives advice on how to live in Mayfair. I wish he had married years ago for he needs the companionship. He’s travelled well; not like me who’s only been as far as Exeter. Getting bored, I leave the street door ajar and walk down the High Street, the wind blowing gently in my face, staring at the advertisements of shop displays; ‘Rentals, a Unique Guarantee. Perfect’ – and all the rest of the words in the dictionary which reduce writing to an empty art. ‘Holiday Offer’ – people can’t think for themselves as the population grows larger, losing sensitivity in external affections.

I stop outside a pub called gold flakes and enter. In the corner, four sexagenarians sit playing cards. From the bar it looks like Twenty One –Barman:

‘What would you like, Sir?’ He speaks in a formal way.

‘Half a pint of bitter, please.’ He fills the tankard and stands it in front of me.

‘One shilling, please.’

I give him two sixpences and sit myself down near an old fireplace. Bitter has a highly active effect on me. First it turns my body cold. Then I have to run to the loo. After sipping the same drink for half an hour, a young lady enters, goes up to the bar and orders a drink. I observe her figure as being rather beautiful, her complexion on the dry side. She walks over and sits beside me:

‘I hope you don’t mind, but thinking as we’re in the same age group, I thought we could have a little talk in addition to wasting time.’ She says this in an Irish accent, unexpurgated.

‘I don’t mind. What shall we talk about? Employment? Records? Accommodation? Travel or society?

‘Romance,’ she says.

‘Speaking for myself, I’ve no frustrations at the moment.’

‘I’ve a problem. My ex-lover has left me in the family way, and I don’t know whether I want it or not.’ She speaks in a voice like velvet.

‘What’s the relationship like between yourself and him?’

‘Oh, he’s quite willing to keep it, if that’s what you mean,’ she says, lighting up a cigarette. She must be in the early stages of pregnancy.

‘Personally, I would have it, for the sheer pain of it all.’

‘I suppose I’m upset that he left me for another girl. I’d thought him more intelligent.’ ‘Drink up and I’ll take you for a ride.’ She looks at me with wonder. We finish our drinks and make our exit.

‘Taxi, taxi –’ A taxi pulls up and we jump in.

‘Take us round the block and drop us back here, please.’ He drives off. ‘You can’t do a thing. It’s a waste of money,’ she says.

We drive around the block and pay the driver five shillings. It didn’t do much, but at least she has a half-moon smile on her face.

‘Would you like another drink?’ She shakes her head.

‘No, I’d better be getting back. I’m staying with friends, and they’ll be wondering what’s happened to me. Can I see you again?’

She takes loose cigarettes out of a packet, pulls out a biro and writes down her name and address. She gives me the empty packet. ‘Annick. 6787 Finchley Road.’ She runs off, hopping on a bus and waving goodbye. I make my way back to Thomas’s place, where I pick up a book on psychology. But I can’t get interested in it. It leaves me feeling abnormal. I try the radio and hear a voice bellowing something out about ‘Generation Z’. So I turn it off again. I fall on the settee, and that feels just right. I begin to dream . . .

I am a ghost, drifting around people, looking at their bodies and watching them in their religious acts. Fog keeps swelling up from nowhere. I see a pop-star change into the dress of an emperor; a herd of poets in paradise playing roulette for beautiful women. Then I see a man with a knife watching me. He throws it and I duck . . .

‘You’re awake, then,’ says Thomas.

‘I must have been dreaming.’

‘By the looks of you, one might think you’d seen a ghost,’ he says, knowing me of old.

‘You know how it is when you dream; you fall under a car; one thinks it’s one’s own end. There’s no escape in dreaming.’

‘You’re guilty about your way of life. That’s the trouble.’

‘Well, as I’m here, I might as well live it up.’

‘You want to find a nice girl and settle down,’ he says kindly.

‘That’s your trouble, not mine; I don’t want birds or babies.’

‘Leda, you’re terribly suspicious,’ he says in a fatherly way. ‘Why don’t you find yourself a beautiful young lady?’ He tries again to order my life.

‘Because I don’t like young ladies and their rubber ware.’

‘Now let’s not have this sick zodo talk. It’s not you,’ he says.

‘I want to stay here for a couple of days. Can I?’

He looks severe and hmmms a bit. ‘OK I’ll leave the window unfastened for you.’ He speaks unwillingly, rubbing his ears frequently to think.

‘I’ll go for a walk then, into town.’

‘Here’s a pound. You may need it.’ He hands me a note; such a dear at times that I feel like pouring cream over him and eating him up. He really is top quality.

Outside it’s raining, but that’s something I love.

‘See you later.’

‘Don’t do anything bad,’ he says, as I close the door on myself.

Outside the weather is a mixture of wind and rain. I am like a savage, without reason, because I don’t know how to use my time or what to do with the life I have; and the only important thing with me is to keep myself clean and to look like I feel. I can’t bear to be frustrated within myself because frustration makes me feel neurotic and completely mad. And I dislike the intellectual groups that base everything on books (without their own experience) and I don’t understand women who say: ‘Nothing is too much.’ And I will never get used to the fact that a soldier kills because it’s an order . . .

The streets look far cleaner once the rain has fallen. I suppose it’s the gloss on the surface. When it rains I feel supreme but other people look so glum like effortless objects.

London itself is having an overhaul because the conditions of many foundations are not so good (but that’s carelessness) and the British love ugliness.

‘Hello there.’ The voice comes from behind me.

I turn and look, but the person I see is nothing in my mind.

‘Don’t you remember me?’ she asks, very sure of herself.

‘No, I can’t say that I do.’

‘Well, you should, because you used to bring me an apple every day to school.’

‘That’s right. 4C wasn’t it?’

‘That’s right . . . my god, you have changed.’

‘Have I? I hadn’t noticed it myself.’

‘What are you doing these days?’ she says.

‘Me. Oh I’m out of work. And you?’

‘I’ve got a husband and three kids. We’ve got a flat in Balham.’

‘Then what are you doing up this way?’

‘I work up here. Every bit of money helps you know,’ she says.

‘Where are the children?’

‘They’re at home when they’re not at school. They look after themselves.’

‘Are you happy?’

‘Happy as I’ll ever be.’

‘That’s good.’

‘I must go and catch the tube now. Must go and get the old man’s tea or he’ll go mad.’ She disappears.

If I went to school with that she must have put on years because I myself am still quite beautiful. Heaven only knows what she’s lost or gained. People are shocking. The first Wimpy Bar I come to I must pop in for a coffee. Not for the coffee itself but because they have paper serviettes and I can drop a line to Terry in Bristol. I haven’t written to him for some time now and I feel he needs the tranquillity of love in a letter. In this way I won’t turn his life sceptic. (What’s he always blaming me for?) He’s a sweet object; the only person I know that doesn’t look like dirty laundry. And eyes like gold sequins. He’s another friend that needs mating and preaches odd ideas without thoughts behind them. I see a child walking towards me eating an ice cream. I can feel the ice on my teeth. Regent’s Park. I’ll walk round it. I don’t know why, but Regent’s Park holds a picture in my mind of a dead bird killed by human hands, and so cold. It could be the zoo or the people, but I’ve never given thought to the matter and I never found pleasure in a zoo in my life. Now the GPO Tower has just come into my view. Built for Mohammed. But it doesn’t annoy me. It’s rather sweet stuck up there, pressed between the sky and the ground.

I love the idea of a Weltanschauung but I don’t have the eyes for it. As a person of many guilts, I feel that the whole value of my body and my mind is built on instincts. Brimming with wishful acts, up until today I’ve always accepted the fact of a little fantasy in my life, but never felt that this fantasy acknowledged my reality. Why has instinct made today an eye-opener, my mind issuing facts through my body with the result that I obtain no satisfaction?

It’s hard for me to believe that I exist and at the same time accept my delusions. (Myself as I am.) On such a realization what can I base my life on? Must I forever live with dreams and fairies? Am I minimising myself so as to hide from my true vocation? Or am I the corruption of what I see?

At this moment I can hardly understand myself, for I am stimulated by my own emptiness and have no idea how to develop the self in me. I am a victim of my own personality, related to no one, not even to my own father; disturbed by emotions that all point to the need for love . . . but until now I never felt myself to be a complete fiasco.

Across the road I make my way into a packed Wimpy Bar. I pick up a dozen serviettes from one table and sit down at another.

‘Yes, sir?’ says a maiden in full battle dress.

‘Coffee, please.’ She dissolves in the distance. Now for Terry’s letter. I’d better leave two shillings on the table for the coffee.

Dearest Terry,

I’ve left the old house and the primitive world, but there’s something new here. One can telephone direct through to God . . . (Sorry, that guy gets me). My love for you is in the first dimension of life and infinite beauty. I neither pretend nor dream about it. It’s Reality.

LOVE

your dearest love

Stick it into a dirty envelope, lick the gum, address it. Now it’s dead and away. Damn my lukewarm coffee. Mustn’t forget to post the letter. Might be a good idea to pop down and see him. I look around at the other people eating and drinking. I notice that a woman has left lipstick stuck to the side of her cup. Feeling sick, I rush out across the street. A careless cat crosses the road. The cars are in his way. I walk through the backstreets for peace and slip into a launderette. The place is empty but warm. I sit down in front of the window and watch the passers-by labouring with their shopping bags. A young boy passes and winks at me. I get to my feet and start walking behind him. He slows down and waits for me. We stand face to face.

‘Don’t I know you from somewhere?’ he says, knowing the truth.

‘I don’t think so, but call me Leda.’ He is full in the face and looks as if he lives inside his body. A jet tears across the sky.

‘Ronald. Call me Ron. I’m making my way to ‘The Rocking Men.’ It’s an all-night coffee bar.’

We start walking. ‘You pay half a crown and you can stay all night, if you want to that is.’ We turn the corner. ‘Can I come along too, or will I be in the way?’

‘Come along. It might be something new for you. I don’t know.’ We make our way into the heart of Soho, into a dead looking alley. A door stands ajar and we push it open. I follow him up two flights of stairs. On the landing he stops.

‘You’d better give me some money to get you in, and for the coffee.’ I hand him a ten-shilling note, he knocks and the door opens, but it’s on a chain and one can see a man, two inches wide and five feet tall.

‘Oh, it’s you,’ says the man, opening the door.

‘I’ve brought a friend along. Is that OK?’ The man nods, and I am allowed to enter.

‘Sit down near the window and I’ll bring you a coffee,’ says the boy and makes his way to a small counter. I sit on a wooden bench under the window. The place is a bit of a mess. Walls painted deep blue, with bad painting painted on the blue. Three one-armed bandits used by seventeen-year-old boys in very tight jeans and shirts. Some of the other teens are in very odd garments. One in a lady’s blouse. Ron is making his way back to me. He hands me a coffee and places the other one on the floor.

‘I won’t be a minute. I’m going to put on a record or two.’

He picks his way back towards the jukebox, stands looking at it, as though it held the interest of a book. It must be the colours. He pushes the button and a loud riff sound, like jazz comes bellowing out from all sides of this two-roomed flat. He starts camping back to me. I suppose it means he’s sending the place up. Bad air fills the place. One boy has a large scab on his face; another just looks plain dirty. It’s a crime to be this poor. Most of them need help or someone to look after them. Ron sits down. ‘Wait until later on. This place gets packed.’ He is full of smiles. Two twenty-nine-year-old navvies enter, with trousers skin-tight, showing all specifications. In the event of a hard-on they’d surely tear. Nothing in the world matters other than their trousers. The mind’s eye completes the picture. One leans against the wall, keeping his arse well gathered in, so that his covered penis catches the point of everyone’s view. I look out of the window and see a group of young lads out for a laugh, but the size of the window breaks my view.

‘Do you know anyone here?’ Ron touches my leg.

I look around.

‘No one.’

‘Do you fancy the one leaning against the wall?’

‘No, he’s not my type.’

‘Am I your type?’ He has fine thin skin, full of youth.

‘You could be.’

‘Well, if I am, tell me. If not I’ll find someone else before it’s too late.’ He looks at me keenly.

‘Surely we can make ends meet somehow.’

‘If I’m inclined to be friendly to the others, don’t take it to heart. I’m only trying to be social.’

A soggy old queen puts her face to his. ‘Will you have this dance with me?’ Ron raises his eyebrows at me, gets up and starts twisting. Someone runs a hand down my back. I stand up and look into his face.

‘You’re new here, aren’t you?’ Death is on his face.

‘That’s right.’

‘What do you do for a living?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Then how do you stay alive?’ he says with his deadpan face.

‘The same way as other people.’

‘You’ve a sugar daddy then?’ He’s trying to make me feel like dirt.

‘I’ve got six sugar daddies.’

‘Do you let them piss over you?’ He’s trying to gain ground.

‘I let them beat me too, then they do what you’re doing. They question me.’ He turns to his adult friend.

‘He’s as camp as they come.’ Ron sits down, looking worried.

‘You’re quite nice yourself, apart from your bitchiness.’

‘Are you trying to be funny?’

‘Oh, I’m quite masculine. I can fight or act out your vigorous role if need be.’

‘Leave him be, Jock,’ says his friend. And with those words, the pair of them move on. I sit down beside Ron.

‘You’re quite red in the face,’ he says.

‘That’s because I’m shy.’

He laughs, and it’s good to relax and listen to the music again.

‘What are you like at sex?’ he says.

‘Fairly well medicated.’

‘I’m none the wiser.’

‘I’ve never got around to doing myself, so I can’t say.’

‘Will you have a dance?’

‘Back at your place I will.’

‘You can’t, I’ve only got one room and we mustn’t make a noise.’

He looks sad. Just then, four more boys in their twenties enter. No one seems to want to leave this place. I see one boy is plastered in paint. I knock my knees to establish sexual desire within myself. Ron says, ‘I’m going to put another record on.’ I watch him disappear into the crowd. He’s fairly handsome. I can see a lad undoing his zip to show his black leather underwear. It looks nice and kinky. I bet his mother pays for his clothes. People have such immodest expressions on their faces. Ron is talking to somebody over by the jukebox. I feel something lacking in me to stay here. It’s the most undesirable place I’ve been in for more than an hour. Ron is back.

‘Someone over there is trying to make contact with you,’ he says.

‘Poor him . . . because I’m with you.’ His grin gets fixed.

‘Do you like me?’

‘I will do in time.’

‘You don’t seem too pleased about the fact.’

‘Of course I am, but I can’t give you my heart here.’

‘True, so very true,’ he sings. I ask him for another coffee.

‘OK.’ He slinks towards the counter, good as gold.

Clouds of smoke drift up and hang under the ceiling like a support. I wonder how many houses have burnt down tonight. Far too many. Ron sits down.

‘Sorry it’s half empty.’

‘It must be hell, walking through that lot.’

‘It is. Someone touched me up coming back.’

‘That shows you’re wanted, anyway.’

‘Ah-hah,’ he smiles all over his face and I have to smile too.

‘You know what I mean.’

‘Don’t upset yourself, love.’

‘Isn’t this music hideous.’

‘Don’t change the subject.’

‘I think it’s a mess, not music.’

‘You’re losing your youth, dear.’ He’s sending me up.

‘I hope not, for your sake.’

‘Look there –’ he says. I turn my head and he kisses me.

‘That was sweet of you.’

‘I don’t want to lose you, that’s all,’ he says.

‘You won’t get rid of me that easily.’

‘Thank God for that.’

‘Why thank God, why not thank me?’

‘Because I believe in God more than I believe in you.’

He gets up and starts dancing with another young boy.

I’ve no sympathy with their way of life. They just hunt or enjoy being hunted. Because their guilt and self-pity is a sickness inbred in them, draining them; so they have to numb themselves with hollow sexuality and the din of the jukebox; inflate their shallow little egos into seeing themselves as supreme men of tomorrow, which they’ll never be. While I, standing beneath my crown of weakness, observe them and recognise myself – as a man.

(Ron is dancing with another young boy who has hair down to his shoulders, swept back from his face like a beautiful Comanche.)

But man owes love to society to bring his standards up to the level of humanity.

Ron returns, looking rather hot.

‘Shall we go?’

‘That’s a heavenly idea.’

‘Goodnight,’ he says to three or four boys. Outside, the night is black as a raven. It’s been raining and the dampness is still in the air. I need a bed with the protection for a child. The city is nearly empty of sounds. We walk in silence, clinging to ourselves for bodily warmth.

‘This is my street,’ he says. It is like a thousand others. I see an old man walking towards me, an everlasting man.

As we pass:

‘Goodnight,’ says the old man, heartily.

‘Goodnight,’ replies Ron.

‘Who was that?’

‘He lives at the bottom of the street. Friendly old guy. He’s friends with the world. Got about twelve grandchildren.’

‘Do you know him?’

‘Look, when you live in a one-bed-sitter, one doesn’t get to know people. It’s only by night that other people live with me.’

He speaks loudly. Walking up the steps he opens the street door, leads me along a dark passage into a back room and turns on a yellow light. There are two apples in ruins in a bowl. The bed is made. I sit at the foot, where a towel hangs waiting.

‘Want coffee?’ He looks down at a tiny gas ring. ‘Well, to bed then,’ he says with more interest.

‘To bed.’

‘Do you mind if I turn off the light? I’m ashamed of my body.’

He moves towards the door and knocks off the light.

As I am undressing I can hear his clothes dropping to the floor. I stand naked and wait for him. He pulls back the covers and puts his knee first into the bed. As he does, I take hold of his testicles and he falls flat on his face and lies there. Letting go, I get into bed. He turns and faces me. We kiss like ladies. We kiss like lords, with him pulling the hair around my middle. I put my hand between his legs and begin to rub his back. He tosses his head to one side and I bite him with kind violence. He bites me back. His head goes under the pillow and pulls out a tube of lubrication, to reduce the friction and half of the pain. He squeezes it onto one of his hands and places it on me (so he’s going to ride me first). He climbs on top of me, and lies there, while his penis stiffens. Then he inserts himself deep into my body. The pain pulls my face out of place. Then I raise myself a little so his testicles beat with his movement (and it speeds up the fact). He slows down and rests on my back as he ejects the cloud of his body into rip-roaring blood, and rolls off me, leaving an exotic smell behind him. For a few moments we gaze at the world in silent peace, then begin to kiss as he starts to lubricate himself. I get on top of him and push his legs apart. As I sink into his body I watch myself, stay there, then become mobilised, my movements making an animal sucking noise. My cheeks go hot, my eyes feel the salt of my blood, and I come a lot. Holding on to him, I roll over until he lies on his back on top of me. We are locked to each other. He rolls off me and we begin to kiss and play with each other’s reclining pile. We feel like two baked buns, pleased with each other, pleased with ourselves. He turns over with his face towards the door. We curl into an S and fall asleep.

Image © Giulio Farella