When I was fourteen, I read The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer and decided if I didn’t start writing my own diary, then no one would ever know how I lived and died. (At fourteen I wanted to be killed in a tasteful, high-profile way.) I bought a notebook, wrote the date on the first page, and began like Laura Palmer: ‘Dear Diary…’ After that, I wasn’t sure what to do. I had to introduce myself somehow. I wrote something like:

My name is Natasha, I’m fourteen years old, and I’m in ninth grade. I do sports: kayaking and canoeing. And I have a huge crush on Sasha Shipulin. He’s going to be a kayaking champion one day. But he doesn’t like me back. He’s so cute and I have zits. Mom said I should bake him pirozhki because the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. I’m learning to bake pirozhki made from yeast dough in the oven.

I reread my entry. I didn’t like what I’d written for two reasons. First of all, it reminded me of a school essay, and that wasn’t what I was going for. Second, from the very first page, I’d described myself in this way… as if I were hideous and fat. And I wasn’t. I did have zits, but my friend Marina said they went away as soon as you fucked a guy. She was already fucking and had verified this personally: her zits had disappeared. That’s why I didn’t want to immortalize my zits or those stupid pirozhki, because all that would change soon. And, besides, comparing my first few lines to Laura Palmer’s diary, I realized all mine was good for was a laugh.

So I ripped that page out.

I didn’t want to write about mundane life. Describing every single day, what I did, who said what to me, what happened – that was child’s play. I wanted to write about my inner world. About what excited me.

The diary should start in a mysterious tone, I thought. On a new page I wrote something like: ‘I am Natalie. I’m 14 years old, but already mature enough…’ I liked what I’d written, about how I was already mature enough. It wasn’t clear what I was mature enough for, but it was good. A promising start. I continued: ‘My love overwhelms me’ (no need to mention that it was unrequited). ‘My beloved is a handsome man with sensual lips. Yesterday, as I walked through the park on my way home from practice’ (no need to say what sport, it lent some mystery), ‘my heart began pounding. I sensed that he was gaining on me, my demon, my dark angel… I turned around, the wind ruffled my blond hair, and I saw him approaching quickly! What came next, I won’t describe here… but it was dizzying. For a long time after, my lips were sore and itchy and his scent lingered on my hands. He walked me to the bus and then retreated into the night. I await my meeting with him tomorrow, tomorrow by the Fantômas statue…’

I was pleased with my writing. Very pleased, indeed. It was like the beginning of one of those novels with detailed sex scenes. I’d read one when I was just twelve. It was called something like The Whore of Venice. Thanks to that book, I learned everything about Venice, mastered some Italian phrases, and stole a few metaphors for copulation. I didn’t want to call sex ‘sex’. Stuff like ‘the unicorn burst into the valley’ seemed more literary and highbrow to me.

Now satisfied with the first page of my diary, I moved on. Although, of course, none of it bore any relation to reality. That evening, after practice ended, I paced outside the boys’ locker room for a long time, waiting for Shipulin to leave. Eventually someone scared me off. I walked toward the park and decided to sit in the reeds by the water and watch the road. When I saw Shipulin a ways away, I was going to sneak out from the reeds and start walking in front of him slowly. He was faster than me, so he would catch up and we would start talking and then he would walk me to the bus. I’d used this trick a few times before, and it had worked. Once Shipulin not only walked me to the bus, but he even bought me a meat pie!

But that evening I climbed too far into the reeds (it was early spring, wet), and my sneakers slid into the smelly, sticky, green muck. I burst into tears and couldn’t stop crying for a while. It wasn’t just that it was wet and disgusting, it also smelled terrible! Then Shipulin appeared down the road not alone but with three boys from his team. I had to sit in the reeds because I couldn’t let them see me in those sneakers. They passed without noticing me (it was already dark), and I trudged to the bus, still sobbing.

I was ashamed to write about that in my diary. Anyone who read it wouldn’t want to keep reading and wouldn’t find out what a gutsy, proud, mysterious, blonde beauty I was. By the way, I wasn’t a blonde. I’ve had mousy hair since I was born. But! In my diary I’d already said I had blond hair and written that scene where the wind ruffles it. I liked all this. Later I peroxided my hair and became a bona fide blonde. This is how the era of lies and diary-writing began.

I reveled in my literary maneuvers, stole from books when I couldn’t find the right words, and fabricated facts and experiences. But the diary was perfect. Almost as good as Laura Palmer’s. In fact, I copied one of her entries in its entirety. It fit my situation: a big, evil grown-up who tortures me, wants to kill me. That was all true. In my life there was a big, evil grown-up who murdered my childhood: my mom’s second husband, my second stepfather. But I was too scared to write about him directly. I couldn’t imagine some future biographers finding my diary and reading the whole truth about what that man did to me. No! No! No! Anything but that! I was incapable of that kind of openness. I’d rather my future biographers read snippets of Laura Palmer’s diary.

That’s why I also lied shamelessly about my ‘first time’. I described my first sexual encounter in detail, using metaphors from The French Love Potion and A Slave of Love. I reveled in romanticizing, even demonizing myself as a femme fatale. None of this had any connection to me or to my ‘first time’. In the diary there was someone else, and it was all consensual, unhurried, and sweet.

Basically, the diary entry wasn’t humiliating – it was nice. Elevating the reader, you might say, to the heights of goodness and love. An alternate reality, a sweet dream, not a word of harsh truth. A few days later, on account of Murphy’s Law, my mom read my diary. Standing over a batch of uncooked pelmeni in the kitchen, she randomly struck up a conversation about what happens between a man and a woman when they love each other, blah blah blah… I realized right away that she’d read my diary and I cornered her. She confessed, ‘Yes, I read it. I have to ask – is it true? You’re not a virgin anymore? You’re really dating that good-looking boy you wrote about?’ (Sasha Shipulin) ‘Yes,’ I replied, ‘it’s all true.’ We shed a few tears over my lost innocence. I said I wanted to marry him and my mom approved (which was weird, because I was fourteen). She clearly realized that I was mature enough, especially since I’d said so on the first page of my diary.

After moonlighting as a young bride-to-be who’d succumbed to love and passion, I went to my room, locked the door, and started rereading my diary. No, it’s all good. I didn’t give anything away. Not a word of truth. Phew.

What would have happened to my mom if I’d written the truth? I really wonder. Would she have killed him? Me? Herself? Gone crazy? Become a religious nut? Cried? Stopped loving me?

Or maybe she would’ve protected me? Hugged me? Taken me far away? Hidden me? No, not likely. Doubtful.

Just imagining what would have happened if my mom had found out the truth… it’s unbearable. Why, though? It’s all in the past! Water under the bridge! I was wise and cunning. I knew that, sooner or later, a reader would arrive on the scene, and I wanted to make a good impression.

I got a little carried away.

After Shipulin broke up with me – well, he didn’t break up with me, really, just stopped walking me to the bus, said he didn’t feel like it anymore – for a humiliatingly long time I wrote him notes and called his house, chatting with his mom for hours about her problems. I even went over to see her, hoping to catch Shipulin, but he never showed up. I couldn’t write about how I was unsuccessfully stalking Shipulin, so I spruced up the story: ‘Fate has separated us… But I’ll always remember you, my angel! The impossibility of touching you drives me crazy. You’re so close, gazing at me again with those dark eyes [though his eyes were actually blue], and I know you want to tell me something. Quiet! Hush! Don’t say anything. We are victims of fate. I know you suffer as much as I…’ and so on. You get the idea. In the diary, I didn’t give a reason for our separation. That bothered me. My reader would never forgive such a blind spot. So then I wrote, ‘I’m dying. They told me it’s leukemia. I forgive you, I’m letting you go. You don’t have to love me. Be happy. They gave me two years to live, and I will love you to my very last breath.’

I really liked illness as a backstory. It explained everything, and I came off all selfless and magnanimous. I even wanted other people to know about my illness. For some reason I told Marina that I had two years left to live. And Marina told Sasha Shipulin. Sasha Shipulin lost his shit and told his mom. His mom lost her shit and called my mom. That was it. I was fucked.

I remember it to this day, like a scene from a movie. The road, lined with pyramid poplars, extends to the sky. Then, a solar eclipse: everything goes yellow and red. I’m walking down the road and my mom runs toward me, wringing her hands and crying. She’s just heard about the leukemia. Ambling up behind her is Shipulin – oh, God! I finally got through to him! Shipulin!

The weirdest part of this story is that my mom never took me to the doctor. She only asked how I found out I was sick. I thought of an answer on the spot: at my check-up they’d taken a blood sample, and the nurse who did the tests said that I had leukemia. This explanation was enough for my mother. Bless her heart… she didn’t question for a second whether nurses are allowed to give diagnoses.

This is what happened. They decided to take me to this healer in Adygea for treatment. It took half a day to get there, to this healer’s place. We all went: me, my mom, Shipulin, and his mom. Once we arrived, we waited a long time in the courtyard. I sat there looking tragic and helpless, like someone with an intimate understanding of life and death. The healer came out and started waving her hands over me. What’s the problem? she asked. Our two moms answered in unison: she has blood cancer! The lady immediately confirmed this: yes, the child has blood cancer, that’s right. Ten sessions. It’ll cost a few thousand [I don’t remember how much she said]. And the cancer will be gone. Both moms jumped for joy. Mine reached for her wallet.

Then the best thing happened: they made Shipulin come with me to my ten appointments. And he did. It was indescribably good. But all good things must come to an end. We went as a foursome to the tenth appointment, and the lady swore that the cancer was cured. To check, we could get tests done. Why didn’t my mother get me tested before paying the lady??? Whatever, her total stupidity was in my interest: I’d gotten Shipulin for a while. Of course, when the tests came back, I was cancer-free. Oh, happy day!

Champagne! Tears of joy! Our moms got drunk and sang drinking songs, while Shipulin and I sat across from each other and smiled reassuringly. But right after the celebration, Shipulin dumped me for the second time. And I didn’t write about that in my diary at all.

Instead, I took pleasure in describing the general qualities of love, death, partings, merciless fate, dreams, veins and blades, voyages, beauty, and eternity. Imagined relationships and adventures. In my diary I was always sassy, proud, and forbidding. But there wasn’t a single description of an event that actually happened. I wrote: ‘The drums fell silent, the hum of voices turned into a heartbreaking wail. I quietly howled into the wreckage of my happiness. A black butterfly landed on my shoulder, fires reddened the horizon. I must go…’ and so on. This abstract bullshit bore no relation to reality, and it filled up my entire diary. Three notebooks, in fact.

Once, I took out a separate sheet and wrote this clumsy passage: ‘Save me, somebody save me. Make him drop dead. I wish he were dead, I wish he’d get hit by a train. I wish his fucking house would burn down, with him in it. When I grow up, I’m gonna kill him. I’ll kill him, Mother, no matter how much you cry. Goddamn fucking Uncle Sasha and my goddamn mother!’

I stuffed this sheet into the back of my dresser, back with all my school notebooks. But one day, when I got home, I saw my mom rummaging through that dresser. I stopped dead in my tracks and finally understood the phrase my hair stood on end. She’d ALREADY READ IT? And she was looking for more? I couldn’t see her face, only her back and hands. Her hands were moving quickly. I was scared to call out to her, I thought that if she turned around and looked at me, already having discovered the existence of this sheet of paper, I would die on the spot. But I had nothing to fear: my mom finally grabbed some stupid magazine about knitting from the dresser and started furiously studying it. I went limp. That night I tore the sheet of paper into little pieces.

After that, my interest in writing fell off. I found a different kind of salvation: a real, long-term, serious relationship with a guy. I started spending the night at his place as often as possible, even though I didn’t love him.

Before long, I went off to university. I got a job in TV. Then I got married. None of this went into the diary. Still scarred, I had stopped writing for three years, but then I couldn’t help myself. I took the diary off its shelf and decided to reread it. I was horrified. On the cover, I’d written: ‘Diary with Exceptional Contents’. As if. That night, I drank a can of Ochakovo gin and tonic, tucked the diary under my arm, and went out to the yard to teach it a lesson. I made a fire and gave the pages of my so-called life a nice toss into the flames.

My friend gave me a notebook with thin papyrus paper for my birthday. When I saw it, my heart skipped a beat. It was perfect for a diary. Not a word of lies in this notebook! I bought another gin and tonic, locked myself in my room, and opened the papyrus notebook. The whole truth and nothing but the truth. Right. I strained myself, trying to figure out what was especially important to me in that moment. Any minute now. I looked around my room. I wrote: ‘I need to disappear from here. Forever! None of this is me. Everything around here makes me sick. Weddings, kids, dogs… it’s not me. If I don’t get out soon, I’ll die of longing.’

There I went again, trying to write all sophisticated. I paused for a moment of self-reflection. Look at this bitch with her literary flourishes! Is it really so hard to write like a normal person? Whatever, to hell with it. At least it was true. True? I checked with myself. Yes, it was true. I really felt this way.

I continued:

Tonight I walked through my yard, where, as a kid, I did my best to make sense of the world. I realized that I’ve changed a lot. I’ve changed completely. The yard hasn’t changed nearly as much. It will give other kids their own sorts of childhoods. I’ve really hardened, but I’ve also become more sensitive. I look at my reflection in the window, the new plastic windows in my horrible room, which I hate so much. People say that your childhood room retains your innocence, your original purity. Mine is skeevy, dusty, and mute. It’s hiding shame. I look at myself in the window and think, I don’t have a home. Technically I do – it’s right here, I was born here, and I grew up here. I’m registered at this address, so are my mother and her newest husband, who, by the way, are fucking in the other room. And that fucker Uncle Sasha? He actually did die in a house fire. His killer finally turned up. Thank God it wasn’t me. Thank God. I go to the hot, gross-smelling kitchen and pour myself some water. I guess this is my home. I know every splinter and creak in the floor. But I have no feelings toward it. This isn’t really my home. So what is? I often feel a vague homesickness. But where home is, I don’t know. When will I find it? What will it be like? I have to leave this city, where everything reminds me what a weak loser I am. I have to leave this city, this house, this yard, these people, my mother, my husband, my friends. I can’t love anyone here anymore. I can’t deal with this anymore. No one can stop me.

I exhaled and reread this. Was it true? Yeah.

‘I’m an asshole. I don’t like people. I don’t know what you see in me, I don’t understand why all of you tied me down and forced me to live with you. Why do you love me, my so-called loved ones?’ I reread it. All of it was true.

I fell asleep, almost happy. But then Murphy’s Law struck again. My mom found my diary and, like before, she read it. This time, she didn’t comment on it, she just took it to her sister’s, my aunt’s house, in the next town over. That evening they read it, reread it, and cried. My aunt drank vodka and my mom took Corvalol. Apparently they talked about how, despite having parents and relatives who were really very decent, I had turned out to be such a cruel and ungrateful bitch.

My aunt summoned me to a café to talk, ordering us both cognac. Then she was like, cut it out with the literary exhibitionism. Maybe you got drunk and felt like writing, but think of your mother.

Thinking of my mother was the last thing I wanted to do in that moment. I’ve been thinking of my mother my whole life, but right then I couldn’t.

My mom agonized over this for a while, she screamed, saying I couldn’t leave like this. Didn’t I love her, my own mother?

I didn’t know. All I knew was that unless I left, I’d start hating her.

She screamed that I couldn’t leave my husband, my job, and her. I was her youngest daughter, by all accounts it was my job to stay close to her. I couldn’t behave this way.

Turns out, I could.

Leaving for Moscow meant steamrolling over lots of people’s feelings. But it didn’t bother me. Not anymore.

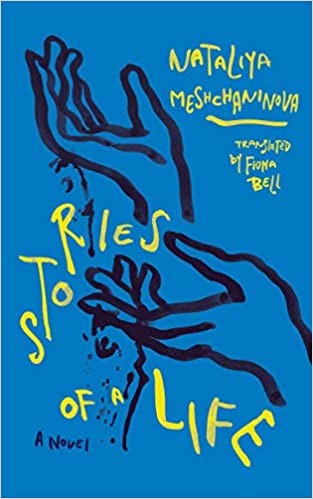

Image © Stu

This is an excerpt from Stories of a Life by Nataliya Meshchaninova, translated from the Russian by Fiona Bell, and published by Deep Vellum Books.