Some of the terms used here to describe Laxmi’s gender and transition reflect her own life and language, and differ from standard descriptions of transgender experience. After an editorial review, changes have been made in order to clarify the representation of transgender identity.

A few doors away from where Anita Khemka grew up in Delhi lived a band of big, sari-clad women with facial hair and deep voices. Her grandmother taught her to be afraid of these neighbours. Whenever Anita was naughty, she issued a portentous threat: ‘If you don’t behave yourself, I’ll send you to live with the hijras.’

Many years later, Anita went to live with the hijras of her own accord, hoping to understand such phobias. ‘I photograph when I feel a compelling need,’ she says, ‘usually when something disturbs me.’

That was when she met Laxmi.

The first son of a Hindu Brahmin family, Laxmi Narayan Tripathi felt neither male nor female. She joined a hijra community, so adopting South Asia’s ‘third sex’, which embraces eunuchs, intersex and transgender people. For centuries, hijras have lived on the fringes of society in closed communities run by potent leaders, or ‘gurus’.

While working on a documentary about the hijra community, Anita learned about Laxmi’s childhood experiences of abuse. She had been raped by several of the men in her family, which had had a dramatic impact on her sexuality. ‘That’s when we first bonded,’ Anita remembers. ‘It took us a few years to start trusting each other.’

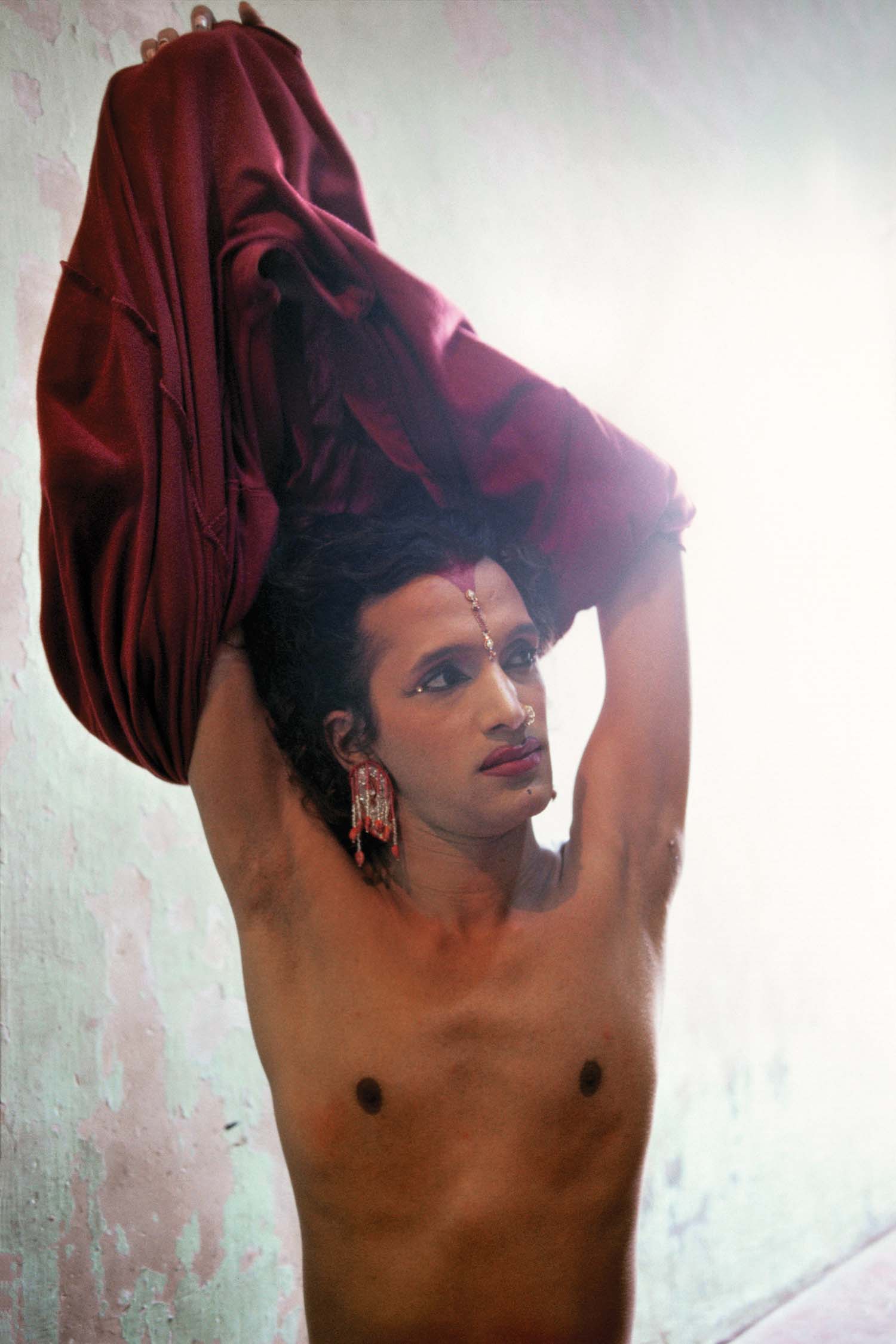

From a young age Laxmi had an aptitude for dance, and dedicated herself to the art as a way of coping with trauma. Traditionally, hijras dance and dispense blessings in the houses of new-born children, for which they often receive substantial offerings of money, and as an accomplished dancer Laxmi fitted well into this role. She had no interest, however, in the other trades regularly associated with hijras today: begging and sex work. Charming and articulate, she had a social vision and knew how to make connections. Anita witnessed the rise of Laxmi’s public profile; over the years Laxmi was invited to HIV conferences and transgender film festivals. She began to travel all over the world. She became a figurehead for hijras and sex workers, including with the UN.

Anita’s documentation of Laxmi developed into what has become a lifelong friendship bound by photography. ‘Sometimes I am with her and don’t feel like photographing her at all, and she says – because she’s a diva – “See how amazing I look right now, with the light falling at this angle. I am giving you an incredible shot. Pick up your camera.” ’

Anita recalls Laxmi’s painful negotiations with herself, her community, and society at large. ‘Early on, she told me, she did not wish to be castrated – the hijras say “reach nirvana” – as that would mean a final crossover of sorts.’ But the ritual removal of the penis and testicles is usually part of a hijra’s initiation, and some began to call her a bahrupiya: ‘shape-shifter’ or, more vindictively, ‘impostor’.

She became a spiritual leader and acquired a following. An Indian Supreme Court judge requested an audience with her. He came to see her for three days in a row, and each time she turned him down. On the fourth day, she received him, and he entered with a young woman. ‘Your daughter is unable to bear children,’ observed Laxmi. ‘How did you know?’ asked the judge. ‘Within a year, she will have a child,’ said Laxmi. ‘When that happens, bring me bangles of gold.’ Everything happened as she predicted.

Hijras of all religions usually embrace Islam, which is traditionally sympathetic to their subculture, and Laxmi loved to visit Muslim shrines. She became involved with a Muslim transgender man. He was a well-known bodybuilder. In 2019 they were engaged at Mahakaleshwar Jyotirlinga temple in Ujjain.

But Laxmi’s public life was becoming more entwined with Hindu nationalism. At last year’s Kumbh Mela, she paraded with the swords and tridents beloved of the ideological movement’s militant wing. She courted the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, whose antipathy to India’s Muslims is well known. She moved to the capital city of Delhi in the hope of entering politics.

She came under attack. Many of her followers resented her alliance with the far-right governing party. They began to question her commitment to the hijra cause. In 2019, Laxmi found herself in a very different situation to when she first entered the hijra community. Eventually, she decided to attain nirvana.

The rituals surrounding gender affirmation borrow from those of marriage and childbirth. After lower surgery, there is complete seclusion for forty days. Then, like a bride on the eve of her wedding, she is scrubbed with yellow turmeric, bathed and dressed in green clothes, a colour that symbolises fertility. She emerges from the house to dispose of her old clothes in the river. An evening of dancing and festivity ensues.

Laxmi now finally finds her soul in harmony with her physical body, and her relationship with the camera takes on a new life. ‘We both know that I will continue photographing her until one of us dies,’ says Anita. ‘She is as much invested in this document as I am.’

Rana Dasgupta