I recently published my first book. Sometimes it is referred to as a novel and sometimes a novella. Descriptions often contain the following words: short, small, slim. I am not bothered by any of these terms. I have long adored a particular kind of novel: short and intense. I have nothing but affection for the term novella – an elegant word and, to my mind, an elegant form. If there is a crossover between the short novel and the novella, it is in their use of language. Every word must count. Such intensity – for both writer and reader – is difficult to sustain. It’s a bit like eating something rich, or spicy – dark chocolate, oysters, Sichuan chilli – you can’t have too much. Although apt, there is something deceptive about the words short, small, slim. What they refer to, of course, is length. My book is one hundred and thirty pages long. There is significant blank space – breathing space, I would call it – between the different sections. Within those hundred or so pages went memories (conjured or imagined), images, dreams, observations, research, other books I have loved and hated, films that have lingered, bricolage from things half-written, and the weight of two-thirds of an abandoned book that came before.

I could say this book began when I read a one-paragraph news story about a nun who gave birth after complaining of stomach cramps, and this would be true. But it goes back further than this, I think. The writing of the book began with my own birth and everything that has happened in my life that would make such a story haunt me, for several years, until I had to imagine a chain of events that led to the ending I had read about. But I worry that even this sounds too simplistic. I think that if we knew, really understood, the reasons why certain stories take hold of us, we would have no need for fiction at all. The strange alchemy of fiction-making, our desire to read and to write it, is still mysterious to me. And it is a mysteriousness that I treasure.

On the difference between writing fiction for children and adults, Clarice Lispector (in her only televised interview, filmed in 1977, the year of her death) said the following: ‘When I communicate with a child, it’s easy, because I’m very maternal. When I communicate with an adult, I’m actually communicating with the most secret part of myself. And that’s when it gets difficult.’

There are some tangible things I could name about the origins of my book. Among them: the news story; a lifelong obsession with nuns (‘Nun!’ I still whisper to myself whenever I see one); a photograph I once saw at a museum in Medellín that featured a sinister-looking bishop; a postcard of the Virgin of Macarena I bought at a bus station in Seville; a tarot-reading television program I stumbled upon late one night in my hotel room in Córdoba; my indignation at the lack of reproductive rights in various countries and their direct relation to colonialism (i.e. the Church); the sexual politics of the adolescent world I grew up in, back home, in suburban Australia. I can name these things, but I cannot trace the origin of every character, event, or feeling in the book. These unknowable things belong, as Clarice put it, to the most secret part of myself. The part which, for reasons I do not understand, I can access only when writing fiction.

Is that why works of imagination still feel so personal? I remember when my book was out on submission – an alien experience for which I was totally unprepared – and I was feral with vulnerability. When things were looking bleak, I told my boyfriend that it felt like a piece of my soul was for sale. I imagined the book (my soul!) on a silver tray being offered around a room, different voices saying: Do you want this? How much is it worth? My boyfriend let out a long breath. ‘That’s just . . . way too intense,’ he said.

‘It either touches people or it doesn’t,’ Clarice said, in the same interview, about diverse reactions to her fiction. And later: ‘I guess the question of understanding isn’t about intelligence, it’s about feeling.’

It is much easier to speak of influence. For a time, I wanted to write for film, and I feel the influence of two reverberating underneath my book: Barbara Loden’s Wanda and Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria. Later, I was drawn to very short stories and so I wrote only very short stories. I was, during this period, exclusively interested in sentences. I deliberated over words. I did not entertain thoughts of a novel. I was quite satisfied. Gradually, after discovering certain authors, I started to think that a different kind of novel might be possible. Different, that is, from the ones I enjoyed reading but could never imagine writing. Of those formative reading experiences, I want to name three works: Marguerite Duras’s The Lover, Christine Schutt’s Florida, and Clarice’s The Hour of the Star. I don’t know how I will feel about these books in ten years. I only know that when I read them they affected me like nothing else had before, and that they changed my approach to writing.

What would I like to read? I often think to myself, and then I go about trying to write it. Throughout the process I am switching roles, from writer to reader, until the lines blur and I need – am indeed desperate for – safe hands in which to place the work. Until that point, though, I like to keep it to myself. I have other writing superstitions, but this one reigns supreme. I don’t know how other writers can talk about their fiction without already having written a great chunk. Another way of saying this is: it has to be a secret. When I wrote the book that I published (different from the book I wrote but did not publish), I wasn’t supposed to be working on it at all. I was supposed to be writing something else. That project felt restrictive, authoritarian, necessarily unambiguous. In contrast, the book became a space of freedom. One where I felt completely in control of the writing – by which I mean sure of the tone and what it was trying to do – and yet simultaneously mystified by the fictional world that was emerging. As detrimental as this shift in focus was to the work I was supposed to be doing, it was miraculous for the book itself. It turned the writing of it into an illicit, thrilling act. It was also, I would later learn, the only time the world of the book was mine and mine alone.

About the unknowable things – the things I cannot trace – if I had to pin them somewhere, it would be to the present moment of writing. Sometimes, a peculiar thing happens when writing fiction. If I were to visualise it, it would look like dominos falling over in slow motion. One word, one sound, one image leads to the next. Rhythm takes over. It is in this writing mode that I am most often surprised by what comes out. I make rough outlines. I have marks that the narrative must reach. But I try to make room for these moments as much as possible, because I think that if I am surprised then the reader might be too. Whenever I encounter this feeling in other works, I feel as if I am there, with the writer, in their moment of fictionalising. The writing begins to pulsate. Good writing, I think, has a pulse. One that envelops the reader in its rhythm.

I am about to immerse myself in the world of a new book. I have been gathering sentences, images, observations and the rest for some time. It feels as though I am standing at the precipice of a mountain above a deep, dark river. ‘A vast emptiness,’ Duras called it, ‘A possible book.’ But I am superstitious, and that’s all I will say.

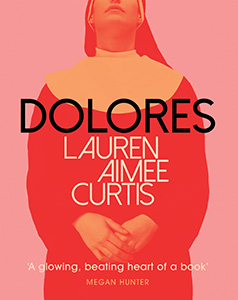

Lauren Aimee Curtis’s Dolores is available now from W&N.