Read an excerpt from Amitava Kumar’s Immigrant, Montana here.

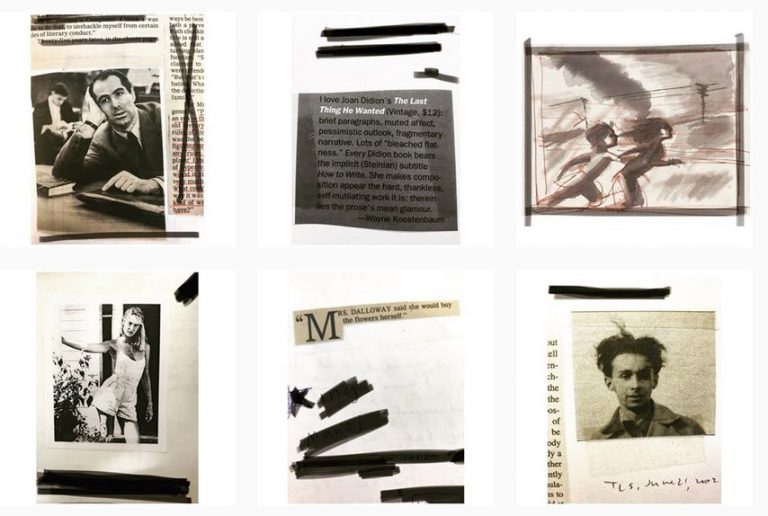

What you see below are images from my notebooks, recently posted on my Instagram. Clippings, quotes, sketches. These notebooks represent the many years I have lived with the dream of a book that turned into Immigrant, Montana. When I went to Yaddo on a writing residency one summer, it was the notebooks that I looked through each morning and night – these notebooks are a visual reminder of all the bits and pieces I was thinking about when writing this novel.

What these pictures do not show is a page from a narrow, reporter’s notebook that I used to have when finishing graduate school. Sitting in an Amtrak railcar many years ago, on my way to a Modern Language Association meeting in New York, where I’d be interviewed and eventually be given my first job teaching in an English department, I wrote the following line: ‘The red-bottomed monkeys climbed down the branches of the tamarind tree to peel the oranges left unattended on Lotan Mamaji’s house.’ I was recalling a childhood memory involving a monkey, a gun and my infant cousin still in her crib. This first sentence later turned into a short-story – I workshopped it in a small writing group, my first, which included a twenty-one-year-old Cheryl Strayed – and then, years later, it became the opening episode in my new novel.

The picture on the top left is of Philip Roth. There’s a story there. I wanted to call my novel The History of Pleasure. The picture in the lower-left row is an image, perhaps from a telefilm, I can’t remember, made from a Joyce Carol Oates story titled ‘Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?’ I wanted sex as my subject, not only the innocence but also the bruising.

Take the image in the top-right corner. It is an image from the storyboard for Satyajit Ray’s brilliant film, Pather Panchali (The Song of the Road). The image appears toward the end in my novel. I was thinking about how ordinary life is transformed into art. I put the picture in the book because I didn’t want the reader to forget that literature arises from artifice. Immigrant, Montana is a novel, then, that is also about writing.

One image that doesn’t appear here is of my narrator listening to the radio. He hears Liane Hansen on National Public Radio saying that a wolf with a taste for sheep has been shot near ‘Immigrant, Montana’. (He has misheard the actual name of the town: Emigrant, Montana.) This little bit isn’t fiction; it happened to me. And in that moment I thought I had found the counterpoint to the story about the monkey and the gun. This new moment caught something about desire and violence. I began to write a novel that would make these two incidents into parts of a long journey from one country to another, and from what one might consider youthful ignorance to something like experience and the ability to work through memories and put down observations on the page.

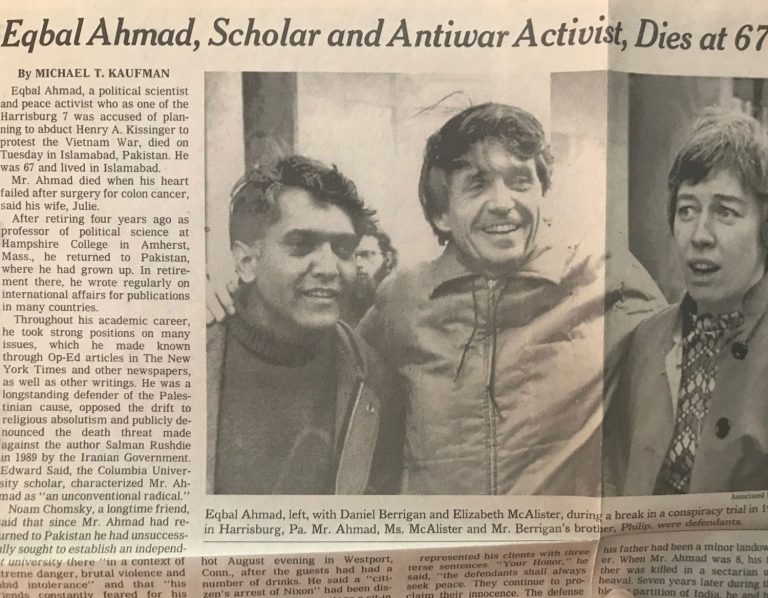

Above is another item from my notebook. It’s a photograph that appeared in the New York Times in an obituary for a man named Eqbal Ahmad. This was in May, 1999. I had never met Ahmad but I learned that he was indicted for conspiring to kidnap Henry Kissinger in a ‘citizen’s arrest’. Ahmad was protesting against the Vietnam War, and his co-accused in that case were Catholic anti-war activists. The obituary also informed me that Ahmad had been born in Bihar, in India, which is where I too was born and grew up. This fact about Ahmad’s birthplace introduced me to what was an extraordinary life. I saw Ahmad as a cosmopolitan who had traveled everywhere; among his closest friends were people like Edward Said and Noam Chomsky, and his allegiance was not with a nation but with all the peoples of the world.

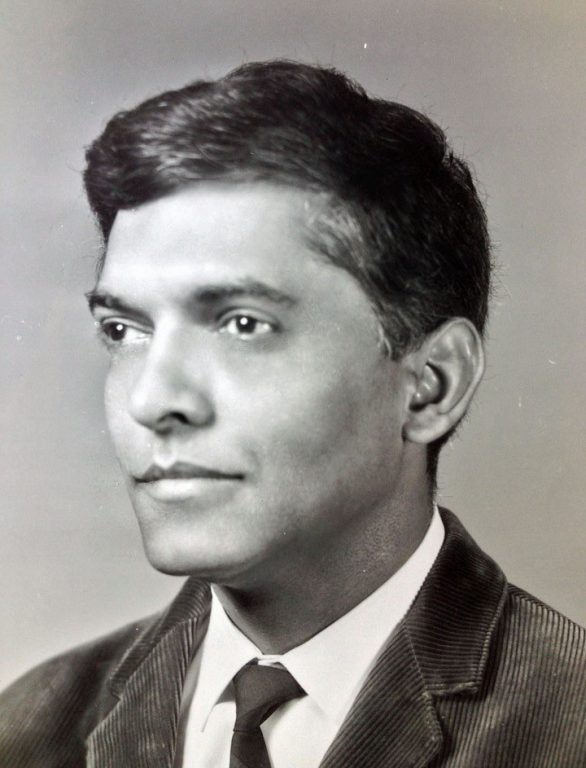

I visited the village near Gaya, in Bihar, where Ahmad had been born. When Ahmad was a boy, his father, who had been sleeping next to him on a bed in the open, was killed by men with knives. This incident had been narrated in a short piece written decades later by Ahmad’s friend, John Berger. In the Eqbal Ahmad archives at Hampshire College, I also found letters that had passed between Ahmad and Berger. Berger was a hero of mine. I decided I’d pick up the story where Berger had stopped. I’d tell the story of Ahmad when he was older, an activist and radical teacher. My novel had lacked a moral center till I decided to tell the story of Ahmad’s role as a mentor to young, immigrant students in New York City.

The photograph you see below was also there in the archive. In Immigrant, Montana, I gave a fictional name to a man modeled on Ahmad because in the end what I was writing was a novel and not documentary nonfiction. I enjoyed the pleasures of invention. Although they had helped me find crucial elements for my story, and though they had served as critical aids, finally, in order to tell that story I had to free myself from my notebooks. And in doing so, I believe, I became a writer.

Read an excerpt from Amitava Kumar’s Immigrant, Montana out now with Faber.