Interleaved with the photographs, more than a hundred of them, in Teju Cole’s new photobook Pharmakon, are a dozen short stories. In ‘The Turbine’, a story in the form of a letter, the narrator writes: ‘There is something I have to say, something I feel it is urgent to say, but I actually do not know, I truly do not know, what it is.’

Pharmakon is Cole’s fourth photobook. Each of them has featured a different combination of images and text. In Fernweh (2020), what might be taken for lines of poetry – in reality, they are decontextualized quotations from a late nineteenth-century travel guide – accompany oblique photographs of Switzerland. In Pharmakon, the appearance of short stories at intervals among the strange, unpeopled photographs produces a stilled atmosphere, both urgent and withholding. We corresponded at the beginning of 2024.

– Alice Zoo

Alice Zoo:

When did you begin taking the photographs that are collected in Pharmakon, and how long were you gathering them? And when did you begin to recognize that a new body of work was forming?

Teju Cole:

The earliest pictures in the book were made in April 2020, the latest in July 2023. Across those three years, I was searching very intensely for the right form; there were a number of false starts. But it was helpful to me that my photographs were being made with the same camera and the same lens. It was important to have a tool I felt close to, and that gave my photos a particular look, no matter where they’d been made. From the beginning, I was following a sensibility; but it was not until early 2023 that I knew what shape the final work was going to take. I made several maquettes, trying out sequences, pasting photos into handmade books, discarding one attempt after another. But I always had the confidence that what I was looking for was already there waiting for me in the growing archive of pictures.

Zoo:

This reminds me of a moment in your recent novel, Tremor, when the narrator Tunde is editing his photographs, and says: ‘These are not the best of the images. They are the ones that tell me in one way or another that they might be part of a sequence with other images.’ It sounds like you and Tunde share this idea of an artwork as something that you’re trying to uncover or reveal, rather than create; a sense that the images find their meaning in relation to one another.

I’ve been thinking about sequencing, and how that might serve as your language, as the medium of your photographic work, rather than it being the photographs themselves. Could you speak more about the process of sequencing?

Cole:

Most photographers, I think, have a preferred way to disseminate their work. Some do magazine work, some do exhibitions – in institutional or commercial contexts – and some are focused on making prints for collectors. For me, the main thing is the photobook and, as you intuit, sequencing is such an important element in making a photobook. This picture, then this one, then this one: you try to imagine the experience of the person who has the book in their hands. As in Fernweh, this new book is very carefully sequenced. Each successive image has to have the simultaneous feeling of being unanticipated and of being right. So, it feels accurate to me that you’d describe sequencing as my ‘language’. The irony, though, is that in another of my photobooks, Golden Apple of the Sun (2021), I jettisoned sequencing entirely, and presented the photographs in a strictly chronological fashion. But that was a one-off, a book that tried to intentionally disappoint some of our expectations of what a photobook should do.

In any case, sequencing is a matter of follow-up questions: there are the questions you ask yourself while photographing, and then the follow-up questions you ask afterwards when looking at the photographs and trying to sequence them. The questions involve slowness, quietness, surprise, continuity, rhythm, repetition or near repetition, and the sizes of images, and the use of white space. All of this is deployed in the service of an apparently simple outcome: that one image comes after another, and another comes after that one, until the book is done.

Zoo:

I’m curious about how text began to find its way into this work. Pharmakon is the first book you’ve published containing short stories, and I wonder whether these were composed with the book in mind, or whether they were written separately, and then began to reveal themselves as being part of this project?

Cole: I began writing the stories at the beginning of 2022. I don’t fully know why. I was nearing the end of writing my novel Tremor. There were things I needed to explore that weren’t really part of that novel’s world. So I began writing these short stories. They came slowly, about one a month. Even though they’re very short, they had a kind of compression and intensity I hadn’t had in my work before, which was exciting. It’s always exciting to discover that you can still spook yourself. I was aware, with the stories, that I was summoning the same gnomic and divinatory energies that had occasioned the photographs. But, yes, only much later, only after I had about a dozen of the stories on hand, did I allow myself to see that they belonged with the photographs. I wonder, actually, whether others will see that kinship between them, between the stories and photographs. It’s there, but maybe not immediately apparent.

Zoo:

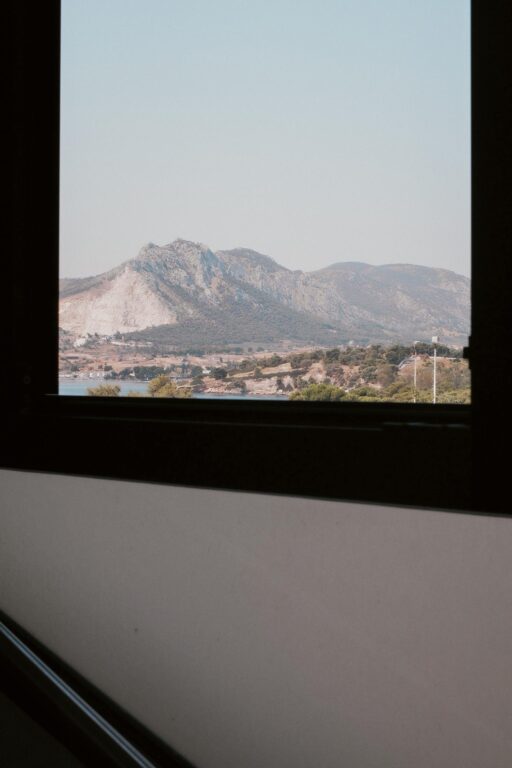

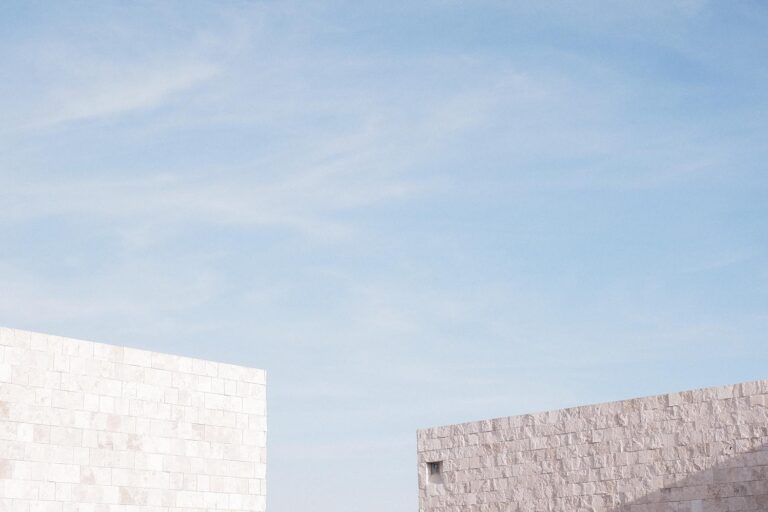

Your photographic idiom seems to have become more refined over the course of your books – more powdery, pastel tones, less saturation, less contrast, cleaner lines. And your focus in Pharmakon reflects this too, so many structures eroded or polished by time and use.

Cole:

That is an excellent description – more powdery. A feeling of the dust settling. In some cases, quite literally so, as in the cases of the photographs from Greece. But more generally, there is a softened, pastel-like feeling, which I think reflects my interest in making images that creep up on you, images that are almost reticent at first. ‘Percolation’ is another word that comes to mind: slow seepage down into some substratum.

Zoo:

The stories, by contrast, are concentrated and intense. The refinement of the images is complemented by the barb of the text; the former quietens and the latter disturbs. In many ways it feels like a book arranged around polarities: image and text, within and without, subtlety and intensity. The polarity is implied, too, by the title ‘Pharmakon’, a Greek term meaning both ‘remedy’ and ‘poison’ – each idea pulls on and complicates the other.

Cole:

I think that’s a fair description. The stories do seem to disrupt some of the apparent serenity of the images. But I’m hoping that there is a unity there too; that, as a whole, it has this feeling of disquiet and unresolved difficulty, with the photographs conveying that feeling the way photographs can, and the stories doing it the way stories can, each mode being true to its own affordances.

Zoo:

Many of the stories look at migration, inhabiting the voices of people trying to flee, people who have been arrested or held. I was struck by the way that, with the stories in mind, the photographs began to accumulate a different, more unsettling charge, seeming to describe obstructions and borders – walls, fences, hedges – obstacles intentionally created and maintained.

Cole:

It’s good to hear that you interpreted the photographs one way, and then, after reading the stories, begin to interpret them another way, perhaps in a more complex way. I would hope that the feedback loop works in the opposite direction as well: that the photographs illuminate the stories. I wonder how that might happen. Maybe, on going back to the stories, a reader might sense in them, in addition to the political distress, a certain stillness, a certain stutter or dysfluency that responds to the muteness of the photographs.

Zoo:

All of this makes me think about portraiture. Over time, fewer and fewer people have appeared in your photobooks – we might see the occasional figure or distant face in Blind Spot (2017), but these have long disappeared by the time we come to Pharmakon (though of course the presence of the human is implied everywhere).

But the stories, unlike the photographs, feel very much like portraits to me. Do you think of them as such? And if so, how do the risks and demands of portraiture feel different when writing, as opposed to photography?

Cole:

I love this question coming from you because you are one of my favorite photographic portraitists. Portraiture is mysterious and difficult. Anyone can point a camera at someone else and achieve a likeness. It happens billions of times a day. So, how is it that certain people – like you, like Fazal Sheikh, like our mutual friend Kalpesh Lathigra – are able to get to that next level? You all regularly achieve something deeper than a likeness, and deeper than a mere play of shadow and mood. And you do it without resorting to gimmicks. I think what comes across in really successful portraits like yours and those of the others I’ve mentioned is a sense of collaboration. Sympathy, yes, but not a sympathy reducible to a sense of flattering the person depicted or making them ‘look good’. Rather, an act of seeing, a sustained seeing that goes well beyond merely ‘looking at’ someone. In any case, it makes sense that it’s the stories in Pharmakon that seem like portraits to you, since they are populated by persons, and that’s the ordinary sense of the word ‘portraits’.

But, for me, there’s also something portrait-like in the photographs. I have thought of some of them, while making them, as portraits of non-human presences. I approached many of the situations the way I imagine a portraitist would (I suppose without the conversational aspect), particularly when I was photographing rocks, boundary stones and shadows. When I photograph a rock, for instance, even when there are formal questions of composition, and foreground and background, and the balance of forms, I still want to do so in a spirit of ‘I and Thou’, the way you would when photographing a person. A roundish shadow falling on a white picket fence is an Other to be approached with some kind of respect, I think.

Zoo:

I’m thrilled to be in that company, obviously. And yes, I do see that: a kind of curiosity and tender regard that is often reserved for human subjects, and which dignifies these fragments of space that might otherwise be unassuming or overlooked.

Thinking a little more about what you say about collaboration, and what that implies about the dynamic contained in a portrait – the portrait as record of a relationship, the photographer as well as their subject – I wonder if you see yourself in your pictures. What have your photographs revealed to you about yourself, the ways you see, the ways you think? And how does the camera change your way of being in the world, relating to it?

Cole:

That’s a good, challenging question. You seem to be saying: if some of these photographs are portraits, are any of them self-portraits? I’ll need to think about that for a moment. I don’t think that that’s something I’ve consciously considered before. But I suppose, given the oblique approach I favor in many of these pictures, they do invite questions about the person doing the photographing. Why does he think this is a good photo? Or, if he doesn’t think it’s a good photo, why has he included it in this sequence? Or, why this approach to photographing this subject and not another approach? And so on. Cumulatively, over the sequence of photographs, I’m inviting the viewer to sympathize with my way of seeing the world, or at least to understand it. There’s something genuinely self-representational about that.

As to whether the camera changes my way of being in the world, I suppose it does. I inhabit any given space with a query: will there be something worth photographing here, or worth keeping? I’ve been thinking lately about this wonderful line from Rilke’s novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge: ‘For the sake of one line of poetry, one must see many cities, people, and Things.’ What Rilke is saying is that the accretion necessary for poetry takes a lot of time and effort. I think something similar happens with photography. You’re out there in the world for the sake of a single photo. It takes a long time to find it, and as soon as you do so, you start looking for the next one, and the next. Years go by; such a great expenditure of time and effort towards such a modest result. And the photographs tell me I’m the kind of person who thinks the effort is worth it.

Pharmakon by Teju Cole is published in the UK by MACK.

Images © Teju Cole. Courtesy of the artist and MACK.