My princess is playing in the garden. In a grove of cedar trees she is searching for her companion, an aristocratic girl carefully chosen for her loveliness, for my princess must have nothing that is not fine in her presence. This girl, who is soft and smooth and sleek like a baby seal, whose brown body the ladies of the court adorn with turquoise and gold each morning, has buried herself in a feathery bed of cedar fronds for my princess to unearth, and my princess, leaning her brow gently against the trunk of a tree as if it were the chest of her father, closes her eyes and counts to ten. At the edge of the grove stands a band of attendants. My princess will play for no longer than a half hour, but still, here stand the musicians with their lyres and oboes, filling the sultry air with music for her pleasure; here stand bronzed boys like statues, holding censers of balsam and incense aloft, perfuming that same air; here stand handmaidens holding silver dishes of fragrant rosewater should she wish to cool her fingers; here stands the nurse, who watches anxiously, whose dark nipples, two shadows beneath her linen shift, still ache from the memory of my princess’s once-aggressive feeding; here stand two robust Syrians who, should she tire, will lift my princess into a palanquin stuffed with pillows of Chinese silk; here stands a venerable wizard of Memphis, foul-smelling with magical ointments, whispering urgent incantations against snakes and scorpions, for death by such creatures is more probable than nature would suggest, and, though my princess is the middle of a litter of six, still there are those who ask, what will she grow into; here stand two noble and haughty Abyssinian ladies of the court, one of whom cradles a mewling lion cub with milky eyes that – when it suckles honey off my princess’s thumb – sends her into fits of laughter, the other guarding a cedar chest lined with melted pearls and filled with amusements befitting my princess’s royal divinity: a pale blue shard of shell from the egg that hatched Helen, tiny clay figurines representing every race under the empire and so lifelike that each took a year to fashion, a burnished pine cone (still fragrant) from the staff of Dionysius, an albino crocodile hatchling (stiff and preserved, with Indian rubies for eyes), miniature plates and cups of beaten gold with which to hold play banquets; here stands the Scythian cook, a gift from the king of Mathura, famed for his temper, and his kitchen boys, whom he beats mercilessly, and who now submerge pitchers of milk in cool river water, who hold forth platters of pomegranate seeds like heaps of rubies and bunches of grapes translucent with sunlight, and who have spent hours decorating in intricate detail a hundred tiny cakes, each with a surprise inside (a toy, a silver ring, a fat fig) on the chance that my princess, who is indifferent to all food, is moved to eat. Here stand I.

We are assembled as we are every morning, but today my princess is in a state of disquiet. There is, as there has never been before, a restiveness in her. She is a great lover of games, of pranks, but today the hunt seems to leave her dissatisfied. She glances around at us, at her nurse, at the pink and blue and yellow villas that dot the palace grounds, as if she suspects us of disappearing when her back is turned and she wishes to catch us in the act. Rose water, pomegranates, silk – none of it will soothe her. I know my princess’s moods; I read them as effortlessly as I read the scrolls in the library. My princess is one of the many languages in which I am fluent. The slackness of her limbs as she moves about the cedars, the wilful toss of her lank hair, the nervous twitch at the corner of her mouth – these are as clear to me as the marks I make on my papyrus, in my own steady hand. I watch as she stops, lifts a knee, and leans forward to pluck off a sandal. The nurse gathers her skirts in her hands and makes to move towards my princess, who says, No! – a harsh word in Egyptian, a language that only she of all her family shows any inclination to learn, since they hold in high esteem their Greek heritage and disdain most things native. The nurse – who cannot read my princess as I do, even though my princess has never said a word to me, and so for me she is like the lost language of some forgotten tribe, I learn without the benefit of conversation – hovers, a gadfly. My princess shakes a surplus of cedar feathers from her small gold sandal. Then she pulls it back on, slopes over to the cedar pile, and points at it, and when the pretty companion leaps up and we all applaud her cleverness, Cleopatra sighs.

I am one of the many scribes of the palace. Of all of the palace’s unseen machinery – its cooks and guards and servants and pages and gardeners and keepers of the royal roses and keepers of the sacred crocodiles and handmaidens and stable boys and soldiers and laundry maids – we are the least noticed, for we do nothing but watch and record. One scribe records the king’s diet and his bowel movements, another the utterances of the royal astronomer, another the portentous dreams of the ladies of court. I could have been the scribe of the graceful Berenice, three years older than Cleopatra and groomed for the throne, or I could have been the scribe of the younger, headstrong Arsinoe, who commands with a pointed finger. Instead I am the scribe of Cleopatra, her father’s beloved, wedged between her sisters. There have been Cleopatras before her, hundreds of them, but only she is mine.

I have known her for all eight years (almost nine, it will be her birthday soon) of her life, from the time that her mother dropped her wailing onto the wooden plank carved with magical hieroglyphs, to now, where she stands alert, the silhouette of her body small and dark in the dappled sunlight beneath the cedar trees. Let me say, in the name of the truth to which I am devoted (for what am I but the most faithful chronicler of all of my princess, her delights and pleasures, the contours of her mind, what she conceals, and what she allows to be seen?), that my princess has not yet achieved what the common people might call loveliness. If she were not divine, if she did not wear the white silk ribbon of a descendant of Alexander upon her brow, if her father were not the king, she would not, perhaps, have been chosen as her own companion. But pretty girls are as transient as the multitudes of apple blossoms that bloom from green branches in a single, spring day, and that by nightfall lie browned and bruised on the ground.

Her handmaidens say that at night my princess howls with pain, that the hollows behind her knees and the crooks of her elbows ache with growing pains, and that she will not sleep unless, as if she were a teething infant again, they rub an ointment of fly dirt and poppy juice on her gums, and I believe it, because my princess grows day by day not into loveliness but into clumsiness. She is a series of sharp angles that will not accede to her will: in the mornings when her nurse brushes her hair she accidentally elbows the old woman in the stomach, and when she runs down the walkways of the palace, which are cool in the shadows of Corinthian columns and lofty palms, she inevitably trips and falls, so that her already embittered legs are further bruised and the nurse must seat her on the edge of her bath each evening and pluck the pebbles and grit of out of her poor, scarred knees. She bites her cuticles, my princess does, she carves tiny cruciforms with a torn fingernail into the mosquito bites on her arms – I have seen flecks of blood on the white linen of her play-dress. She picks at the corners of her mouth until the skin bleeds, and when it does, as she sits with her tutor and practises her Greek vocabulary (oromancy, chyme, panselene) she worries at the sores with her unconscious tongue. Of late, she blushes, as if someone has dipped a brush into ink and touched it to her cheeks. A blush of shame, I believe, at her body’s constant betrayal.

I am to keep a record of her days: here did Cleopatra, daughter of Auletes, appear in a procession at the palace at Memphis and pay honour to the gods, her sisters by her side; here was Cleopatra presented with a dress of fine-spun gold by the society of silk merchants; here was Cleopatra presented to the visiting king of Mauretania, who praised her pretty manners. These facts give the shape but not the colour of my princess’s days. And I am a poet, not a keeper of kitchen accounts. Great sand dunes of scrolls we scribes produce, to be poured into the thousands of cubbyholes in the library of Alexandria, and there they lay unread, for the library contains every text in the world, more than can ever be read even by the scholars that toil there constantly, and to their burden we daily add more. The dutiful journal I file alongside the rest, so that in time it will serve to cross the eyes of some future scholar with boredom. The real work I keep for myself. My secret pleasure: the reams of papyrus that I fill each night alone in my chamber, with every detail of my princess’s day, accounts of her shifting moods as one might record the changing weather. What I do not see I gather, for I am trusted all about the palace, and what I do not gather I imagine.

This morning Cleopatra awoke at dawn. The city of Alexandria was turning from ivory to rose, the sun touching sweetly the columns of the white marble palace, the limestone sphinxes that line the avenues and the pearly domes of the Greek temples making the wide expanse of the desert and the crumbling tombs of the kings blush pink. Cleopatra lay abed in billows of lambswool and panther skin, her eyes lifted to the sky above her balcony, where birds of prey swooped and dove, and beneath which Alexandria turned aureate, roseate, alive. Rising, she let out a cry of horror. A tacky substance, for a moment utterly mysterious, was stuck to her thigh. Then, the realization. She had gone to sleep with her favourite pet – a white mouse who would scurry in panicked bursts over her childish arms and tremble in her cupped hands – and sometime in the night she must have crushed him, because now in the chaos of her sheets was only the approximation of a mouse, a flattened lump of fur, bulging something red and intestinal at the mouth, pathetic and small. Cleopatra wept. Three times. First, with the shock of disgust, like any healthy young girl. Then, with a tender, biting remorse, because she loved her pet, loved him as she does all things that love her and bring her pleasure. But what of the third time? There, as she wept in her bed, like a small figure lost in drifts of white sand, her grief slowly began to clear, like mist dissolved by sunlight, and the world around her began to emerge, once more new and unknown to her, as if each of her senses had been gifted to her again, as if she had only just come into them. The cloying scent of roses and lilies from the bower above her bed, the soft brush of panther fur against her childish ankles, the buzz and rattle of a dying beetle in some corner of her chamber, the rising heat from the city beyond the balcony, and beyond that the great untamed world which she could feel but not see – its multitudes of people somehow pressing against her – and above it all, the pleasing resonance of her own sobs, echoing off the marble columns and rising in high, pure notes to the ceiling. Cleopatra twisted and turned in poses of despair, explored modes of sorrowful repose. Now she was Achilles, wild with grief over the slain body of Patroclus; now Demeter, lying in anguish in a field of poppies. Oh, how she wept! What good are tears if they are not beautiful? How much more lovely is one’s grief when it is known to be seen? The nurse was fetched, to witness what the handmaidens had discovered upon entering the chamber: the wretched figure of the princess kneeling on her bed, her hands clawing at her hair, as if she would tear it out. They tended to her, administering calming draughts and cool cloths to her flushed face. In the commotion they did not notice at all the body of the mouse – now hopelessly lost among the tangle of the bed sheets – nor the tiny tortoiseshell mirror: a small, still pond placed between the knees of a girl who had wished to admire the comeliness of her own tears.

Not long after – as she is every morning – my princess was dressed (holding her arms out as if she wished to be picked up, the nurse lowering her shift onto her lanky, boyish body), and led from the chamber to the sound of musicians playing pipes and stringed instruments, her face shining like a clean little moon, her limbs scented and aglow from a bath of precious oils, her hunger satiated with a breakfast of milk and honeycomb, and something in her aspect irrevocably changed. It was time for her lessons – three stifling hours of them. Her tutor’s room is small and exhibits the most irritating kind of false modesty – he has a simple cot that one cannot help but notice when walking into the room, but that upon closer examination reveals itself to be of the finest ebony. He is Roman, the type who stumbles through Alexandria speaking only Greek and Latin, believing the common languages beneath him, and as a result being cheated every day in the marketplace. He is short with the servants, annoyed at the smallest of crimes (the wine too sweet, the drapes open when he wished them closed), and they fear him. He is a large man, ox-like, with hair like a sheaf of wheat atop his big round skull. His teeth are rotten. He is famous among Alexandria’s many scholars for his poetry, which he is ready to recite and hold forth about at a moment’s notice, without even an invitation or the excuse of drunkenness, poetry which I have always thought pointlessly ponderous, much like his body. He takes up so much space, hunching broad-shouldered through doorways, yet he never seems concerned by it, never considers how he might be crowding out the rest of us. His eyes unsettle me the most: eyes like two grey pebbles protruding, watching everything, interested. When he considers Cleopatra’s answers to his questions (Who are Aphrodite’s parents? Is it better to be the lover or the beloved? Why do the Romans believe that the Egyptian seasons and the Nile run backwards?) he lifts his gaze to the ceiling, rolls his big wet eyes, and pushes the septum of his nose upwards with a thick forefinger.

Cleopatra is nothing if not talkative, particularly during these lessons, which she attends to with fervent devotion. Like anyone with whom she has occasion to speak, from her nurse to the woman who braids pearls into her dark hair and asks if they’re arranged to her liking, she interrogates her tutor on subjects beyond the remit of the occasion: his childhood, if he has nightmares, his favourite foods, the name of this fruit or that colour in the language he spoke at his mother’s knee, why he has chosen to wear a blue robe today rather than the red one. He does not have the will, or perhaps the imagination, to answer; he sticks to the lesson plan. If her mind is a river, quick and lively, he is the great stone that sits in the middle of it, interrupting its flow and rebuffing its touch. He never notices me where I stand every morning in the corner of the room, a mute witness to the lesson, placed like an ornament between the nurse and the servant who carries a pitcher of watered wine.

I have never been able to sleep, not since I left home. As a boy in Samaria my father had a vision that I should be a priest, and so he sent me away to Jerusalem, where, with six other boys with whom I could not speak, all of us having different languages, I was cut into perpetual virginity and trained, from dawn to dusk, in letters. When they could not make a priest out of me, I went to Tyre and found a job on a merchant ship, tallying goods. Then one night, like all young men of the empire, I found myself, inevitably, in Alexandria, alighting under the fierce eye of its great lighthouse, which winked at me slowly, as if to say, I have been expecting you.

Even for someone who will always be a boy, Alexandria has its pleasures. At night I walk its streets and, I confess, I imagine that Cleopatra is with me. I talk to her; I show her what she will never learn from her tutor’s questions about units of grain and the migratory patterns of ibis. Leaning as she does against the parapet of her balcony in the day, she sees an Alexandria of sunlight: silk banners shining and rippling proudly in the breeze, streets shimmering, sphinxes and statues of the gods glowing nobly. This is the world in which she belongs to her father, her tutor, and her nurse. But night is a different world. Not all can understand it. One must navigate through the murk by the distant glint of the stars, adjust one’s eyes to the pellucid moonlight. The loveliness of a world under daylight is apparent, but it takes a certain kind of knowing eye, a certain kind of imaginative soul, to understand the beauty of the evening’s chiaroscuro, to prefer the strangeness of the world as it is obscured by the indistinctness of shadow. These things I know. These things I can teach her. I am a person of shadows. I understand them. I know what the world is really like and what its true substance is, and so each night I lead the ghost princess at my side past the statues that glow spectral and strange, away from the palace shining like a distant, white tomb. In the inky gloom we wander the streets, two inkier shadows, and I say: Cleopatra, please observe: the smell of charred meat mingling with the scent of the sweet, rotten water pumped from the perfumeries along the river; the laughter and soft music drifting from the brothel windows lit pink and green, behind whose gauzy curtains all men of the empire are rendered equal, the centurion and the slave aligned in their desire; the rancid stink of the tannery and its strangely coloured pools in which men frequently drown; the hup, hup, hup of the Nile as it laps its banks, and the whimper and groan of lovers hidden in its rushes; the sweet odour of urine at every street corner; the beckoning and cajoling song of the women whose work can only be done at certain enchanted hours, whom for a small sum of money will perform spells or mix love potions; the yap of feral dogs; the soft chants of the eastern men in saffron robes behind the high walls of the monastery; the nasal strains of snake charmers; the wailing of infants from the house of the woman who takes the babies of unwed girls and whose dirt floor is a graveyard; the whisper of fountains from walled gardens; and the agitated chatter of mongrel languages from low houses and gambling halls, for in Alexandria all the world is absorbed and blended together.

In those hot, daytime hours before playtime, when Cleopatra recites verses from Ovid in her tutor’s room, and he sits there with his fat finger on his puggish nose and corrects her Latin, I retrace our steps from the night before. There is always a moment in which I come to believe that it is only our bodies that are present in the tutor’s room – her soul and mine are elsewhere, her real self is next to mine in the nocturnal softness of the night before – and though she does not look at me, though she will never look at me, we vibrate like strings strung next to each other – if her tutor plucks at her, if the world commands her to play, I too quiver. I resonate with the music that vibrates within her.

Now, though, in the garden, playtime is finishing. The nurse is wiping away dirt from my princess’s face and fingernails with a cloth doused in rose water. The kitchen boys are being herded along to the hot ovens over which they must suffer, the untouched cakes in their hands. It is high noon, and Alexandria is at its most brilliant. In the marketplace the stalls will be shuttered against the relentless beating of the sun’s brightness for an hour or two; the sacred cats that stalk the palace gardens and for whom the cook prepares special, costly dishes of songbirds will declare a truce with the cobras and nap in the dusty beds beneath the rose bushes; in the library the scholars will sit down to plates of bread and chickpeas and let the words in their brains subside to a dull roar; in the brothels the women and musicians will just now be getting to sleep, curling up in shaded rooms, their bodies and instruments for a moment at rest. It is time too for Cleopatra to retreat to her cool, cavernous chamber, to eat a dish of cucumber and radishes soaked in cold vinegar, and sit on a bench of marble, her maidens at her feet, until the sun has been driven into a more forgiving afternoon sky.

But something is not right. The world, which should be melting into soundlessness, is filled with crackling noise. There, over the balcony that lines the palace garden, something is happening on the broad avenue and steps that lead up to the palace. The shouts of a crowd. Though we cannot see it, no one could mistake that atmosphere, the air crackling with some terrible possibility. Etiquette dissolves. The Syrians, ever alert to risk, rush to the parapet. The kitchen boys hesitate, pause mid-march, caught in the uncertain landscape between obedience and betrayal, but finally one cannot stand it and breaks away, and the others follow – the Scythian cook who once held them in absolute control now powerless to command them. Under the cedar trees, the handmaidens cower, and the Abyssinian ladies stand together, nervous and at a loss. The musicians saunter over to the parapet in an exhibition of restraint, wondering aloud what gives, exchanging self-conscious banter. The wizard of Memphis demands that a servant put him in the palanquin, but nobody would pay him any attention even if his voice were not lost under what is now a surging noise – one so loud that it has awoken the palace, whose doors vomit out servants and scribes and astronomers and chambermaids and builders all into the garden. Only the nurse stands alone, beckoning to my princess’s pretty girl companion, who weeps out of surprise. My princess is nowhere to be seen.

I join the crowd at the parapet, nudge an oboist aside, and look down onto the palace steps. There are hundreds of people massed together here. Speculation and knowledge, indistinguishable from each other, make their scuttling way down the line of those gathered. The crowd below contains the prostitutes of the city – women in flashes of crimson, emerald and gold – and a handful of priests in their white robes, the rest of the crowd, a dingy lot of market sellers and street boys, who, seeing such a strange mingling of the sacred and profane heading towards the palace, had not been able to resist joining in.

A woman in a green robe has emerged at front of the crowd, being pulled by her elbow towards the palace steps by a man in white. She seems reluctant, pausing every few steps, but then we see it is because she is reaching into her robe to take something out, an offering, perhaps, a small, orange object. But what kind of offering is this, for whom the crowd is not silent and reverent, but surges and swells with furious encouragement? The woman walks up to the palace steps – green against that gleaming, untouched white – and places the orange object upon them. The breeze carries the sour, oniony tang of the massed people up to us on the balcony, and I swallow my disgust. The woman in green buckles at the knees, lets out an agonised wail. A cat, the oboist whispers to me, and I hear it go down the line – a cat, a cat, a dead cat.

Now, from stage right below, a new action commences, and all of us on the balcony press forward and lean over to see, and for a moment I worry it will not hold. Below us, the crowd surges forth like a wave from one side, and throws up a man, kicking him onto the steps, arms here and there reaching out to rain blows down upon him. From here I make out his sheaf of wheat hair, his great mass, being rolled onto the steps like a stone. He cowers in a ball, places a useless arm over his face. Isn’t that –? someone asks, and, He looks like –. Yes, it is he, and it becomes clear what he has done, that somehow he is responsible for the death of this cat, and the parapet is filled with the buzz of communal thinking. It is discerned and determined: Cleopatra’s tutor – who some have seen walking through the corridors of the palace as if he were himself a king, or been berated by him, or witnessed him stumbling and drunk in the city’s brothels – has killed the prostitute’s cat; all cats, whether owned by prostitutes or kings, are sacred in the city, and the fitting punishment is death, and the people of Alexandria have brought their proof and the culprit to the palace, and they are desirous of justice.

Someone is emerging from the palace. A figure, walking briskly, flanked by two men in white robes. The line at the parapet murmurs: the king! It is Auletes, Cleopatra’s father, a soft little man who prefers to spend most of his day playing the flute, sitting in a tub of scented water, while handmaidens dance about him. Cool water probably still clings to the nape of his neck, the pads of his fingers are likely pruned and wrinkled. He will be wanting to get back to his bath. He has never been one for statesmanship. He hustles on short legs towards the crowd, his pate glinting gold in the sunlight. When he reaches the top of the steps, he raises his hands. He is speaking. We lean over the parapet to listen. In this brief, subdued moment, I hear the distant cry of the nurse behind us, like an anxious seabird, calling yet for Cleopatra.

We can hear very little from here. Auletes moves his hands as if conducting music, I catch a few words in Greek, which only a few in the crowd will understand, they turn to each other confused: this man and hasty and stay and go home! But it seems to have an effect. The timorous Auletes has done something, the crowd is quieter, though not quite still – the people shuffle around, a sense of puzzlement hangs in the air, a mild current of chatter and debate. Every now and then there is an outraged comment, and a few people at the edges of the assembly drift off. But the woman in green remains, on her knees, her head bowed in submission, the cat dead on the steps. Auletes does not acknowledge her. Cleopatra’s tutor is curled up like a fat grey snail at the bottom of the steps, where the crowd left him. Go home! Auletes shouts, again, a tremor in his voice – though also, I detect, a note of satisfaction. The crowd murmurs – they seem persuaded, if dissatisfied. The tutor moves his arm from his eyes, peeks at the king.

But now. The palace doors flash open, and something comes forth. A little streak of white: her play-dress. I’d know that gait anywhere, that enthusiastic run that usually ends in a fall, but now she stops, and begins to walk deliberately towards her father, each step incredibly slow, as if she were a bride taking measured steps towards her groom. The ribbon upon her brow dazzles – as if Helios, at the helm of the sun, has finally found the object most worthy of his brilliant caress. My princess moves, unhurriedly. Somebody shoves me aside, a warm bulk at my elbow – Cleopatra’s nurse. She says the princess’s name softly, sounding disappointed.

Cleopatra has reached her father. With those slow steps, she descends towards the woman, who has yet to lift her head, but, I think, or perhaps I imagine it, is trembling with anticipation. When she gets to the orange offering Cleopatra kneels before it. The woman bends her face lower to the ground, touching her forehead to the marble steps. Cleopatra is still, and somehow all the fervour, all the emotion of the crowd seems to have become condensed in that small figure, indistinguishable from the white of the steps, her dark hair a smudge against them. There is an expectant pause. Everyone is waiting and no one speaks. All eyes are on my princess, and I feel as if I have been joined by a host of people, as if the crowd looks with my eyes, as if, in my looking, every soul in Alexandria is behind me. There is no sound.

And then, a singular noise. Like a high note on a flute, it emerges, silvery in the air, gaining strength, until we realize it is the sound of weeping. Cleopatra is crying over the cat’s body. Her sobs intensify in pitch, and the crowd begins to move, begins to swell once more. No! – her one Egyptian word, rising high above the noise of the crowd, the purest sound. No, no, no! Her voice sounds younger than it does in her tutor’s room or in her chamber. It is voice of a little girl in a nursery. Her small hands move along the orange body, as if feeling for something inside it, as if she might discover life hidden in that pitiable heap of fur. The woman presses her forehead hard against the marble steps in supplication. A priest lifts two arms into the air, and issues a rallying cry. A noise that one might mistake for thunder is rising from below: the communal growl of the crowd. Up here on the parapet, people put their hands over their mouths, murmur to themselves. I glance at the nurse, looking for some reaction, but her face is uncomprehending: she does not yet understand.

When King Pentheus – whose name means grief – banned the women of Cadmeia from worshipping Dionysius, who loves those whom all else disregard, prostitutes and slaves and silent women and those of the shadows, Dionysius took revenge, and sent the women of the king’s family into a Bacchic frenzy. King Pentheus, dressed as a woman and spying upon the frenzy from behind a tree, was mistaken by the women for a leopard, and in their state of ecstasy, wild-eyed and dancing to drums, they tore him to pieces with their bare hands, his mother lifting his dismembered head high upon a spike, ferocious with enthusiasm, the spirit of the God turbulent and sublime within her.

In the movement all I can see, visible through the gaps, are flashes of the most tender parts of the tutor’s body – his flank, his round heavy belly, his soft back – and then those tender parts do not appear anymore, then, there is not one whole piece of him left. He has dissipated as if he never existed, the crowd has absorbed him, consumed him. Someone lifts a trophy up into the sky – a small worm-like object that was once the tutor’s most prized part – another stumbles away, grinning, his mouth smeared with red. There is the raw smell of meat in the air, the smell of blood baking in the hot sun. The smell of a charnel house, of the skinned bodies of goats and sheep that hang grotesque from the butcheries at night.

I turn my eyes to the small figure on the white steps, who bends over the orange cat, still lying intact on the palace steps. The crowd no longer has their eyes on her, their master, as they move at her feet, turning and moving as if each of them were lost in their own private dance. But she is unmoving, fixed in a position I recognise, like a statue, her hands frozen like claws at the side of her skull in a perfect attitude of anguish, as if she would tear her hair out. I am quite sure, beneath that dark hair, she is smiling.

* * *

I do what I have never done. I go to my scribe’s room, which looks out upon the marshes, and which is in a part of the palace long neglected, dusty and dark between the kitchen and the stables. I ignore my desk, and lie down instead on my plain-wood cot. The heat in the room is suffocating. I stare at the gloomy ceiling, watching a fly buzz half-heartedly. He is missing the party on the steps of the palace, where, emptied of people, the flies and beetles sit down to a banquet.

At first I do not know how to read what my princess has done. Watching her I had felt the confusion I felt as a child in a room full of children babbling in other tongues, who looked at me with dark eyes, who pointed and spoke to me and seemed to tell me something urgent, but whose sounds remained just that, incoherent sounds. I lie on my bed and I think the mystery through, just as I do when I come across some obscure word in one of the library’s many untouched texts, written in a language I know well, in which I otherwise dwell comfortably – if I know the context, I can discover the meaning.

I understand the shape and reason of her tears – she wept to show that she wept. I know that in that moment she felt torn between two worlds: that of her father, the small sunlit figure behind her; and that of the rippling sea of humanity before her, the people who exist solely that she might one day rule over them, who yearn for something terrible, whose outrage will turn easily to lust in their longing for ecstasy. What she did was, I think, an act of something approaching love. The way one might allow a beloved dog that scents a hare to spring from one’s side and bring it down for the sheer joy; the way one might allow a favoured servant to sing while making the bed, disrupting the stillness of the morning. She granted the people her favour. She let them unleash their fury in her name. She said, I am one of you. She said, I love you.

* * *

‘When Cleopatra was nine . . . a visiting official had accidentally killed a cat, an animal held sacred in Egypt. A furious mob assembled, with whom Auletes’ representative attempted to reason. While this was a crime for an Egyptian, surely a foreigner merited a special exemption? He could not save the visitor from the bloodthirsty crowd.’

Stacy Schiff, Cleopatra

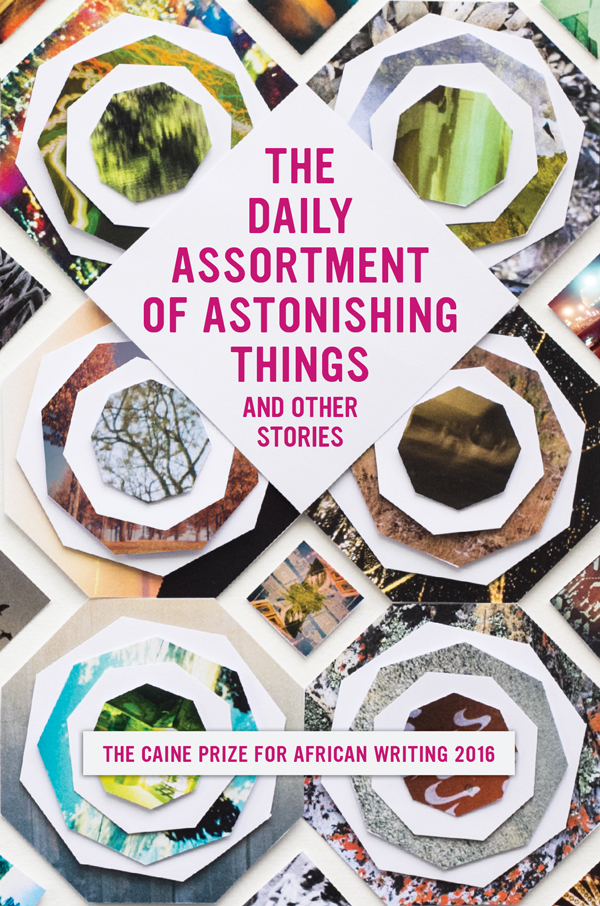

F.T. Kola’s ‘In the Garden’ is collected in the Caine Prize for African Writing 2016 anthology, The Daily Assortment of Astonishing Things and Other Stories, published in July 2016.

Cover photograph © Ashley Van Haeften