Over the long summer of 2020, poets Will Harris and Sophie Collins emailed back and forth from their homes in London and Glasgow. Harris’s debut collection RENDANG was published in February 2020, while Collins’s debut Who Is Mary Sue? appeared in 2018. They compare dreams, describe their rage at global events, and consider the ways they each show themselves to the world.

Will Harris:

I haven’t been sure where/how to start this conversation, but it’s the start of a new week and I’m feeling a speck of hope for the first time in a while. Maybe it’s because I’ve just woken up (for the second time) and drunk a pot of coffee. Maybe it’s because earlier – too early, sleep has been erratic lately – I checked my phone and saw that councillors in Minneapolis had voted to abolish their police force and replace it with a community-based model of safety and support.

I’ve just been reading about a group of local organisers, researchers, artists and activists called MPD150 who put together a ‘performance review’ of the Minneapolis Police Department in 2017 to coincide with its 150th anniversary. It’s amazing to think of the work they’ve done to imagine a better future, and now to make it possible.

When I get wrapped up in the news cycle, especially in the last few months, it can feel like the present is all there is and that it’s unrelentingly hopeless – a plugless hole into which everything is being sucked. It’s easy to forget how recent so many institutions are, how fluid. If they’re ‘fixed’, it’s only by the assumptions of their time.

As Hegel said: ‘all institutions that serve us also have an intrinsic tendency to autonomy, through which they come to serve their own interests at our expense.’ Carol Anderson’s White Rage is good on this, describing how the wounded rage of the white South in the US shaped the laws of the Reconstruction era and beyond. In this country, I wonder if it’ll be possible for us to reimagine our institutions – or to abolish them – when they no longer serve our needs. Can we honour the hope of the oppressed instead of the rage of the oppressor?

It was pure joy to see that statue of Edward Colston toppled and thrown into the Avon at Bristol Harbour, from where so many of his slave ships would’ve set sail. And yet some people – including the Leader of the Opposition – tried to dampen that political joy, to bring the conversation back to law and order. Edward Colston himself broke no laws. But laws change. Those clerical responses feel like the spluttering of institutional rage, desperate to reassert its legitimacy, terrified of hope, of imagining new possibilities.

I don’t know what poetry is meant to do right now. Last night, I fell asleep listening to a conversation between Susan Howe and Adrienne Rich. The last thing I remember is Rich reading from ‘The Phenomenology of Anger’. Lines about the enemy ‘computing body counts, masturbating / in the factory / of facts.’ That phrase has been ringing in my head this morning, too.

How have you been doing?

Sophie Collins:

I’ve been in a real funk since I received your email, perhaps since last summer – or the summer before that, even. When I say ‘funk’ I mean a kind of mental fug of the worst kind, which I’ve experienced as a constant sense of struggling uphill, of moving against a newly forceful and malefic gravity when faced with even the most basic of tasks. I’ve been unable not only to write but also to read and retain ideas, and it’s the latter that I’ve found to be the most disconcerting. But I’ve been here before.

There are plenty of statues to be taken down in Glasgow. Last year, during Black History Month, I went with a couple of friends on a walking tour of Kelvingrove Park, during which the park’s colonial relics and the ways in which the space had served colonialism were pointed out to us. One of the things that stayed with me was when the tour leader, a lecturer at Glasgow, brought us to a halt on an unremarkable stretch of green. Here, she told us, was where, in the 1800s, entire homes – portions of villages – had been displaced from various parts of Africa to Glasgow so that the Scottish people could gawp and baulk at African bodies, their ways of being.

I bought a beautiful, early edition of Rich’s Diving into the Wreck in New York a few years ago, and I often go back to it. I reread ‘The Phenomenology of Anger’ after receiving your email, and it was the following lines that stood out to me:

Fantasies of murder: not enough:

to kill is to cut off from pain

but the killer goes on hurting

Not enough. When I dream of meeting

the enemy, this is my dream:

white acetylene

ripples from my body

effortlessly released

perfectly trained

on the true enemy

raking his body down to the thread

of existence

burning away his lie

leaving him in a new

world; a changed

man

This part feels rooted in a retributive logic, but then there’s the ‘changed man’ in a ‘new world’, and the poem goes on to speak of a situation that is ‘no longer viable’, of a phoney progressivism: ‘I hate your words / they make me think of fake / revolutionary bills / crisp imitation parchment / they sell at battlefields.’ This brings my thoughts back to the work of groups like MPD150 and the discussions – ongoing for years, but now so much more visible – of a future informed by transformative justice.

I’ve been dreaming wildly in lockdown. Have you?

Harris:

Your email has been circling around my head over the last few days. My first response was to start multiple unconnected paragraphs, and since I’m writing an email – rather than longhand – maybe I can try to write it all out, even if it gets tangled.

1: Mental fug. I know it well. I mean, I know my funk. I assume it’s different for everyone – with different causes and symptoms – but I’ve felt something like it since I was little. The malefic gravity. Or to me it feels more like a fissure, the kind that opens up when a star implodes, dragging matter inwards. When I was younger, I had no clue how to deal with it. I’d stay up late, drink coffee, drink, eat skittles, write something, reject the idea of writing, write about it.

I experienced it as a total out-of-sync-ness: my mind and body wouldn’t line up, wouldn’t work together. When I first saw a therapist I told him it was like my feelings were buried under ten feet of concrete. How was I meant to reach them? Recently, on good days, if I wake up early enough I can get a few weightless hours.

Do you link the particular fug of the last two years to publishing small white monkeys and Who Is Mary Sue? They came out in the same year, didn’t they? And Currently and Emotion, which you edited, came out just before then. All those books – those projects of thinking and reading – seem interconnected. Did they feel like the culmination of something? I suppose I’m also implicitly asking how I should feel after publishing a first book, what I should be doing . . .

One thing I’ve taken from your work is its simultaneous density and lightness, this sense that beneath the controlled surface there’s an agonising dialectic playing itself out between shame and selfhood. This tension is resolved – temporarily – in the idea of translation. Or translation in the sense Walter Benjamin writes about:

Just as a tangent touches a circle lightly and at but one point a translation touches the original lightly and only at the infinitely small point of the sense, thereupon pursuing its own course according to the laws of fidelity in the freedom of linguistic flux.

Sometimes I feel suffocated by shame, like it’s a kind of cling film wrapped around my face that trying to peel off only tightens. Benjamin’s image of a tangent and circle – aside from its geometric beauty – feels like a sigh of freedom.

I think I read those lines when I was first beginning to understand myself in terms of race and racialisation, and I found them useful less as a theory of translation than as a theory of identity. It reminds me of how, in your collection Who Is Mary Sue?, you describe the figure of Mary Sue as ‘an unwitting embodiment of the double standard of content’.

That double standard is also a double bind: it says that as a woman – or in my case, as a non-white person – you’ll both be expected to write about your experience and judged for doing so. In spite of that, maybe it’s possible to take up a different position in relation to the ‘content’ of your life: to touch upon it ‘lightly’, as a tangent touches on a circle, to maintain that ‘freedom of linguistic flux’.

2: An unremarkable stretch of green. There’s so much in this image of that park in Glasgow that gets to the crux of the problem. It feels like the confected rage at the loss of those ugly, pointless statues is just a diversion. Pretend you care about statues, so nobody notices the rest of it: the gardens, the houses, the institutions, the laws. Pretend you care about statues, so nobody looks around and sees the violence, the barbarity, the emptiness. Sometimes I think they couldn’t care less if we tossed all the statues into the sea and razed the buildings and dragged up the roads. Because they’ve won. You can’t purge what’s gone. You can’t breathe life into absence.

I think about those colonial-era documents destroyed by the Home Office in 1961 to avoid ‘embarrassment’; documents that detailed the torture and murder of unarmed civilians in Kenya, Malaysia and British Guiana. One surviving record, stored at the National Archives in Kew, describes a detainee in Kenya who was ‘roasted alive’. The idea of typing those words out on official, headed paper (‘Her Majesty’s Government’) to be filed away in Kew is perverse. But it gets to the heart of this country: we should look at an unremarkable stretch of green and see the depravity hidden there.

3: ‘Fantasies of murder: not enough’: It’s powerful to think about Rich’s poem alongside ideas of retributive justice and abolition feminism. That ‘not enough’ sticks in the throat. It feels like a challenge not just to ‘kill the cop in your head,’ but to think about what healing might look like. The range of different experiences you talk about – including your own – shows how hard it is, maybe impossible.

Never having been a victim of violence I’m wary of taking up any space on this subject. My experiences of anger and hurt sit in my body. Years of insults, minor slights, which come out in welts of shame. It’s not the same thing. Still, I think about healing. In fact, I think about your poem ‘Healers’: ‘We are rarely independent structures she said / before she dropped a bolt pin’.

4: Dreaming wildly. Last night I dreamt that jalapeño pretzel bits were on sale in Lidl and that I couldn’t find my laptop. Vivid, but not wild. What have you been dreaming? Last week, a friend showed me a poem called ‘Say It’ by Jayne Cortez – it does have an explicit ‘dream’ at the end, but the whole thing is composed in this dreamlike, id-first, incandescent way:

Slide on fingernail filth

of your larva of triteness

become honorary shithead in

your own mouthful of erected statues

break through your own face of accumulated door

slams bam bam bam bam

Hope you’re well! I’m just about to pick up a new bike in Deptford, and excited about being able to roam the roads again.

Collins:

Someone I’m close to once described to me a similar sensation, that of being at least one remove from their own feelings. My feelings, however, are always so close to the surface; I have almost the opposite sense of living so totally inside them that it seems impossible to hide my interior state from others. Even when I’m deep in the fug, as I have been these past few weeks, and at a loss to articulate myself, I am sure that my blankness is being broadcast to all I encounter.

The funny thing is, people often see judgement in me, but in considering this just now I believe that what’s interpreted as judgement is in fact an inability, on my part (and I’m sure many others experience this too), to perform affectively, in the expected ways. To react instantly to a given piece of information with certainty, in either the positive or the negative, to reassure the object when you, the subject, have no stable footing from which to exert that force of comfort.

I’m not plugging this as a virtue, by the way, but rather trying to say something about the way in which ambivalence – a genuine absence, or at least a deferral, of judgement – is sometimes understood as the opposite.

There was a recent interview with Sianne Ngai, promoting her latest monograph, that mentioned gushing. I sometimes experience a visceral response to gushing, like hearing nails on a chalkboard. This is from the interviewer’s introduction: ‘the overwrought speech of gushing is an act of aesthetic evaluation that is itself aesthetically compromised. Gushing, Ngai writes in Theory of the Gimmick, “is the sound of someone falling for a gimmick.”’ I haven’t got hold of Ngai’s new book yet, but, according to the blurb, a gimmick is something that is overrated, ‘devices that strike us as working too little (labor-saving tricks), but also as working too hard (strained efforts to get our attention)’. I think my reaction comes from a similar observation, that gushing is a compromised evaluation, but rather than making any deductions about the thing being evaluated, what I hear is an aesthetic compromise via disingenuousness. Because it often seems as though the gushing person hasn’t in fact decided on or yet understood what their response to the object actually is. So gushing can sound to me like pure incongruence, like someone ‘faking it’.

Relating the fug to the books is interesting. It definitely feels like those three books, which were written and published in close proximity (in 2016, 2017 and 2018), were part of the same cycle. My subjects in those books were, broadly, as you say, shame and selfhood. Even in Currently & Emotion, an anthology, I see these concerns borne out in discussions of translation which foreground translators’ visibility and attack both common misconceptions of translation as an impersonal, mechanical process and the colonial ideologies manifest in the ways in which translations are published in the UK.

The last two to three years have been about initiating a new thought cycle, I suppose, so I shouldn’t be too hard on myself for not producing (euw) during that time. Things are changing now, and I’m similarly working on two or three writing/editing projects in tandem that all have the same founding preoccupations, namely: intimacy and honesty (congruence!).

Probably this is the case for all writers – though maybe some more than others. Judging on the connections I’ve drawn between your books, Mixed-Race Superman and RENDANG, I would guess you work in a similar way? I remember when we spoke recently for a University of Glasgow event, I was drawing all sorts of lines between the two, but that you seemed a little ambivalent about these? I think the connections are less explicit than those between Mary Sue and small white monkeys, which are in fact identified and named by me in the latter, but maybe the more implicit kind of cycles only become clear to us with enough distance? What are you working on now?

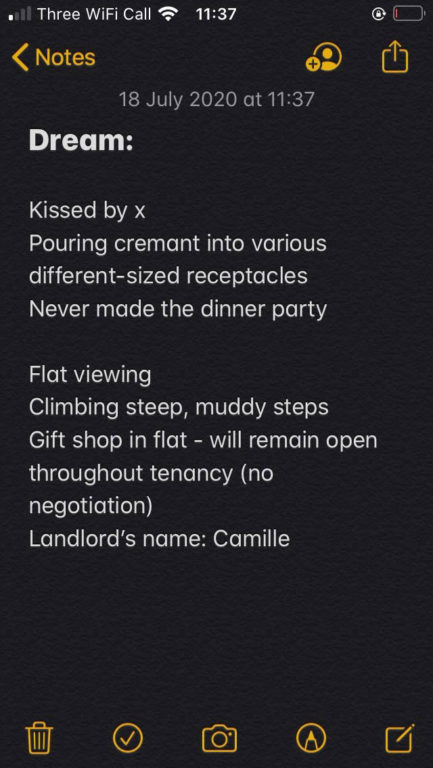

Dreams. Yes, I’ve been dreaming a lot in lockdown, which I remember seeing somewhere is a common experience, something to do with the quota of new thoughts the brain must generate per day (and this not being fulfilled during a typical quarantine day) and/or an increased sense of ‘unfinished business’, which is what dreams deal in. Here are my notes from the night before last:

Perhaps the content gives you some sense of what currently feels unfinished for me.

Harris:

That sounds difficult. These last couple of years I’ve been lucky enough to get by writing and doing online workshops and other odd jobs, keeping myself to myself, taking for granted the absence of that pressure in my life: a work environment where my feelings are other people’s feelings. But I worry that having more control over my routine has made my moods more fragile, turning me into some variety of houseplant that needs to be watered with a pipette and given exactly two hours of direct sunlight a day.

A friend once told me their feelings were like a river flowing through them constantly, which amazed me. Similar to what you were saying, they seemed incapable of not feeling their feelings. ‘Feeling their feelings’ is such a weak phrase. Why is the English language so bad at expressing abstract thought? Like it was primarily designed to discuss football and bread.

Since starting therapy I think I’ve got better at feeling my feelings too, or more aware of the extent to which they’re there, exerting some force or other, conditioning how I act and what I do, even when I’m not aware of it. And ‘knowing’ that has helped explain some strange symptoms and phobias – like for a while (I don’t know if this is embarrassing or weird, or both) I had a fear of bridges. Even low, sturdy ones. Which at least means I can test how well I’m doing just by trying to cross a river.

I hadn’t heard about the new Sianne Ngai, but it sounds good. Gimmicks and incongruence makes me think of being ‘online’. Sometimes I get disturbed by the dissonance you end up internalising when you spend too much time there. The gap between intimacy and affect. The gushing. The algorithmically-driven language. My book being out in the world has probably added to those feelings. I get queasy/anxious thinking of people reading it and seeing the ‘I’ in those poems as simply representative of me (seeing me, in turn, as a representative for the book), and inferring my identity and beliefs from it – by which I mean misconstruing them – though that’s part of the deal of publishing. You let yourself be made into an artefact that can be given and taken and mistaken.

It only recently occurred to me that the titles of my two small books are ironic, which must be a learnt response: a pre-emptive form of defence (keep the feelings at bay so they can do less damage). RENDANG is mostly about London and mistaken connections (between people and words), not food or Indonesia. Mixed-Race Superman is mostly about ‘Great Man’ history, race science and the failure of liberal rhetoric, not a celebration of mixed-race identity or superheroes. It’s like I wanted people to misread me, as they do – in person – every day.

Maybe what links the cycle of writing that led to those books has to do with not knowing. A belief that the pressure to know is fundamentally violent, whether it’s applied to oneself or others, and that not knowing – choosing not to know – doesn’t imply a lack of interest. Not knowing is the starting point for self-education, solidarity, action.

I love your dream(s). It’s like a fully fleshed-out sitcom premise. And I now know what cremant is, which is not what I thought, i.e. milk jelly. What do you do with your dreams?

In return, this is a photo of Rotherhithe Tunnel, which I made the mistake of walking down on my way to Deptford a couple of weeks back.

I don’t know what I’m working on. This evening, I thought about rewatching Titanic and/or writing a script for a zombie movie, but instead watched the first twenty minutes of Ghost and wrote this email. Which pretty much sums up where I’m at in my thought cycle.

What about you?

Collins:

Your fear of bridges sends me back to Rich. I remember reading somewhere (a pretty long time ago now, so I could be mistaken) that she developed an acute fear of stairs shortly before the psychic breakthrough that led to drastic shifts in both her life and work, including her divorce. When I was younger, as young as eleven or twelve (prepubescent), I suddenly developed a fear of escalators. I couldn’t tell you what brought it on or how or when it receded. But the common factor here seems to be, perhaps, a sense of impending change? Or the need for it? (And so, too, potential loss?) It’s funny you include the tunnel photo here because it seems to speak to that idea, of reaching a mid-point at which it would make as little or as much sense to turn back as to keep moving forward . . . There is something panic-inducing about this (at least to me)?

When it comes to publishing, I seem to have developed (with respect to my books, if not articles, interviews, etc., which feel more immediate) a convenient lack of object permanence, meaning that I can forget, for the most part, that they are things that exist in the world that others have access to. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend it, though, as it makes reviews all the more excruciating! It sounds like you’re in the process of integrating, which is much healthier, I think.

Frankly, I don’t do a whole lot with my dreams; they’re too banal for poems. I remember someone assuming that ‘The Engine’, the long poem that runs through Mary Sue, was a recounting of a dream. I was surprised and offended: are other people’s dreams really that baroque? Do I not seem like someone who could invent (may I direct you to the title essay?!)? The other night I had another house-viewing dream in which I was being shown round what was essentially a mansion made up of many, many adjoining rooms, each of which – whatever its purpose – had a bath.

Anyway, I want to apologise for more delays at my end, which were not due to the fug this time, but quite the opposite: my mood’s been so much better the past two weeks or so that I’ve been too busy being a person in the real world to want to turn back to the screen. That might be an over-exaggeration (of course I’ve been online), but I’m taking pleasure again in seeing and speaking to people, in reading and in my surroundings. I recently had a flat move, the third in a year, and hopefully the last for a while.

Yesterday I left Glasgow for the first time since March to visit a friend in her new home. It was strange and also not at all to be on a train. I felt my system react most strongly – overwhelmed, but in a way that was both invigorating and calming – when we passed a medium-sized body of water. I haven’t been able to swim since the beginning of the year. I’m hoping there’ll be the opportunity to do that in Italy, where I’ll be seeing you next week.

—

Harris:

It’s nice to look back over this intermittent log of quiet despair and claustrophobic rambling. I wish we could be writing to each other from the ‘other side’ of things, but I’ve lost all sense of what side we started from or got to or where were we even going in the first place – all I can say for certain is that it was probably always wrong because assholes were driving the car.

One big thing skewing my sense of time at the moment is the feeling of repetition in a vacuum: talk of lockdowns, no deals, layoffs, rising death tolls, the latest Tory refusal to do something minimally humane like extend free school meals. Everything is the same, but different. Or the only difference is the shifting jargon of ‘circuit breakers’ and ‘tiers’. I wonder if that’s why people seem increasingly blithe about the state of the things. Horror has a short attention span. Once bitten, immediately forgotten, etc.

Most of the trees on my street have turned cowfish yellow. Atoms are raining down through the void. Children are screaming. Adults are ignoring them. The local park is the same unremarkable stretch of green.

The other night, I dreamt that I was in an old lake house (a horror film-style lake house on stilts, shrouded in mist) and I was trying to communicate with other people there, but I couldn’t speak. I was constantly changing shape – first I was a fish and then an octopus and then a different kind of fish – and no one could understand me. And then when I finally settled back into my own form, the person I wanted to talk to was wearing a bowler hat and looking wistfully into the middle distance.

Sometimes I think the worst thing about life – or my worst fear about life – is that you only realise how sad you were, how wrong or stuck, by the time it’s too late.

But it’s good chatting.

Collins:

Repetition yes. We’re doing it now. Phone calls are all the same too. No new news but bad news. All the obvious stuff (Tories putting the hoarding of wealth above absolutely everything else, above life; US election doom; threats to Roe v. Wade), and then, today, I read that, based on a study carried out by ‘experts’, the Netherlands is considering a law that would force contraception on women with psychiatric illnesses, learning difficulties, Hepatitis B or C, or a history of child abuse. Abject.

Your dream is about bureaucracy? Is that too on the nose? Am I projecting? Hats are about thoughts, and the type of hat can indicate the type of thinking. But I notice you don’t mention who the person wearing the bowler hat was – is.

I haven’t been dreaming myself – or, not in the way that allows you to recall the dream. I have been writing, though. And thinking more clearly. More complex thoughts. The fug is still at bay. Maybe it’s a trade-off.

Chatting is good! An actual, good thing.