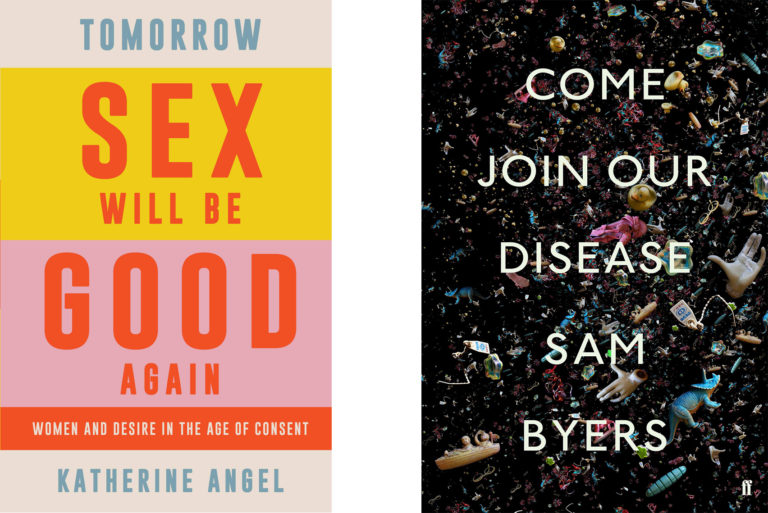

Katherine Angel’s Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again examines female desire, consent and sexuality in an era of social change, questioning the belief that women must be certain about what they want in order to ensure their own safety. Read an excerpt. Sam Byers’s novel Come Join Our Disease charts the fortunes of a homeless woman called Maya, who agrees to a shady rehabilitation program run by the philanthropic wing of a corporate tech company. Read an excerpt.

The two authors came together to talk about writing into uncertainty, geologic time, and ‘replenishing the mulch’ of ideas with ancient and mythic texts.

Sam Byers:

Katherine, it’s great to be having this conversation with you, and I wanted to acknowledge first of all that it’s really the continuation of a conversation we’ve had right through writing our respective books! I know that there are issues in this book that you’ve been thinking about your whole career. I also know that you wrote this book in a moment of great urgency and immediacy – you were at work on it right when the Weinstein allegations broke. How did you balance the pressures of the moment with the need to reflect at greater length, and how did you balance that in turn with the need to express things you’ve contemplated for years? Do you feel that now, as I do, these timeframes have very much found their perfect convergence as the book comes to publication?

Katherine Angel:

Hello Sam! I’m so happy to talk with you too. Our first books came out around the same time in 2012, and now these ones are coinciding too; they’re book-pals. I think both our writing has gone through a lot of changes in the past nine years, unsurprisingly perhaps. What I love about your books is the way they speak so uncannily to the moment, without being limited or exhausted by it – and I think in your new book, there’s such an interesting centrifugal movement between two poles – that of a hyper-contemporary scenario, as you always have your eye so acutely on where we are, and something deeper, more existential and mythical. I love the way this new book brings those two realms together – between the urgent, chaotic, hyper timescales of the present, and a deeper, weirder sense of time. That’s what I want to ask you about: the experience of writing books that seem to capture something so acutely of the moment – in a way that can feel almost psychic or prophetic! Books take a long time to grow; do they feel different as you’re writing them from how they land?

I’ve wondered myself about the question of time in relation to my new book. In one sense, I wrote this book over years – really, years and years. Agonisingly slowly, haltingly, confusedly. But then there was a moment, a while after MeToo, when time sped up. The whole MeToo phenomenon – and the sense of urgency and speed of it, the sense of something being recalibrated, sometimes chaotically, in the culture – made me see material I had been thinking about for a long time in a new light. I realised that work from way back, during my PhD, about sexual function, arousal, and so on, was really pertinent to questions of consent. And I realised that I felt worried about some of the urgency in the culture; worried that, in our haste to correct wrongs, we were in danger of not thinking through certain truisms: about women’s duty to speak out, to know what they want and feel and be forthright about that, as a condition of their own safety. So I then felt it was important to try to articulate my misgivings about the very well-meaning rhetoric that was emerging after MeToo.

I often think about how stuck I got at a certain point with what eventually became this book, and how it coincided with feminism taking on a new presence and character online. I was watching online feminism become, like everything else on Twitter, increasingly embattled. I was learning and thinking a lot – Twitter really could and can be marvellous in this way – but I was also experiencing a sort of muteness and inhibition, a need to burrow away and think, quietly, alone. So the manuscript I was working on became a bit frozen, and I did too; and then, once MeToo was unfolding, and as I was feeling very conflicted about it – namely around the burden placed on women to do the culture’s ethical and political thinking for it, through their duty to speak out (whether about past wrongs or about their sexual desire) – suddenly a momentum built up, and then the book came very quickly. That often happens with me: years of pressure building, and then a dam bursting. I wish it was a smoother process but sadly it’s not. And as often happens with my writing, the way through ends up taking the form of writing into my ambivalence, and trying to show not a position but a person grappling with something.

There’s always a tension for me between speech and silence – in my life, in my writing – which is in fact what the book is about: the ethical and political risks of making speech the key site of feminist rhetoric about sexual violence. I really value silence, and think it is dangerous to undervalue it or stigmatise it.

Byers:

A lot of the time what I’m doing when I’m writing is just kind of holding everything open. Perfidious Albion especially was this very deliberate experiment in immediacy and absorption – really a test to see whether the novel as a form could ever remain open enough to keep pace with contemporary life. With this new one I had more of a fixed sense of what I wanted to do because the protagonist, Maya, her voice spoke to me very strongly, and so I felt, in a happy way, much more limited in my choices.

What you say about this sense of the mythical is so interesting because that’s exactly where I felt I got to with Maya, and now I can’t find my way back out. All the writing I’ve done over the past year has really been purely mythological. So it’s a double-edged sword because I do feel I struck on something with that weirder, deeper sense of time you’re describing, but in doing so I rendered the present unworkable, or exhausted, and now the journey back into the present feels like a long one, or one I’m not sure I want to make.

I think what we’re both kind of pressing at here is really the question of language and form. It’s so interesting that you talk about this ‘frozen’ place, but then beneath the surface of that frozenness this build-up, as if all the ideas were immanent but unable to find the right form or vessel. I wonder if that was not just about the cultural climate but also, for you, about what I think is quite a profound shift in both form and intent. I remember you saying that with Unmastered, you were not even sure as you were writing it that it was a book, until finally you realised that the form in which you were recording your ideas was actually the form the book needed to take. And I think that book retains that sense beautifully, as if you are in dialogue with yourself, or addressing yourself. It’s intimate and in a sense quite private, and in being so it holds space for a lot of uncertainty, ambiguity, nuance.

With this book, it feels like you’re operating at multiple levels of direct address: you’re addressing the moment, you’re addressing other thinkers, you’re addressing the culture, you’re in fact writing into the culture. And what’s really interesting and to me very radical is that you’re doing that by demanding space for uncertainty and vulnerability, for an alternative to what you call ‘confidence culture’ and this constant injunction to know, categorically, what you want, and what language you need to express what you want. You’re talking very specifically, obviously, about desire and consent and the blurry complexities of social interaction as embodied through sex, but that idea struck me as having huge wider significance. So often as writers we think of ourselves as ‘using’ language, as if the trick is just to know language and then to deploy the right bits of it strategically. But I wonder if what we’re often doing, and what you were doing as this book took shape, is writing towards language, or circling language, until finally, having discarded a language that doesn’t work, we come to rest on the form of expression we need?

Angel:

God yes! I really don’t experience writing – or speech or life – as just about using a language that is already pre-existent. I think things would be much easier if I did. But I experience it as an attempt to wrestle something out of the language that is given to us, and often trying to refuse certain forms of language – instrumentalised forms, language that already assumes what is important. I mean, that’s impossible to do, but I think it’s worth trying.

That kind of wrestling with language can feel painful, I think – and it makes speaking about the writing quite challenging – the need to find exactly the right words, to navigate traps . . . I realise that sounds like a tortuous and paranoid relationship to language. I have always felt an affinity with that quote, attributed to Thomas Mann (I know we are both fans of his!), that ‘a writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people’. I don’t want to romanticise the idea of writing as torture, but really, for me, writing isn’t just about expressing ideas well or accurately – it’s about finding the words and the form for ideas and possibilities that our social language itself, our inherited language, with all its burden, makes difficult to even articulate. So it is a bit tortuous frankly. Hence years of editing . . .

Speaking of Mann: it’s just occurred to me that there is something of The Magic Mountain in Come Join Our Disease. The membership of a new sort of organisation, culture, or cult; the appeal of both health and sickness – health as fetishized, but a fetish in the name of which we can enjoy our symptom, luxuriate in it; the way Hans Castorp journeys into this new world of devotion to illness and its cure, or merely its management? And his sort of release into sickness, his revelling in abjection or ‘failure’. Is that fair?

I’m curious too about what you said about a resistance to the journey back into the present (also a theme in The Magic Mountain). I know you’ve been immersing yourself in a lot of very ancient texts the past year or so – and had a conversation with the brilliant Jenn Ashworth on Twitter about your need to ‘replenish the sources’. How do you feel about the relationship between this kind of ancient material – the ground and sediment of culture perhaps – and the now? Is it hard to bridge that gap? I feel like being on Twitter can make one forget that not every book is Just About to Come Out.

I also want to ask you: how does one deal with being on Twitter as a writer? Its frantic pull towards the now, right now, now! When writing is also about larger structures of time and text, and quietness and slowness. It’s such an ongoing battle for me. How do you deal with the different time signatures of your writing life?

Byers:

What you’re saying about writing not just being about expressing ideas well or accurately, which I totally agree with, and which I think becomes more and more the way I think about what I want to do in my work in the future, reminds me of another discussion we had once where you pointed out that in fact expressing something really well can be dangerous, almost seductive, because if you’re a writer with a convincing style you can actually convince yourself of something you don’t believe simply because the way you’ve formulated it has a certain superficial allure. And I think about that a lot because I know I can do that. I can sort of distil something into a line I like, but then because I like it as a line it’s hard for me to tell if it’s actually what I want to say. And so sometimes I feel like this whole idea of writing being ‘good’ or ‘great’ or something is a massive trap in itself – one that encourages us all to strive for the brilliant at the expense of the true. And so I wonder if that’s really another aspect of the time you give your writing – the necessity to look at something a year later and say, does this still ring true?

And I think it’s perfect to talk about Mann here because Magic Mountain, which I read a few years ago, changed my life by changing my conception of time. For me the whole point of that novel is that Castorp doesn’t just leave mainstream society, he leaves social time, and enters instead a strata of time closer to the geological or perhaps even the cosmic – time that is almost the absence of time. I don’t think any other novel has made me so aware of that other timescale, and being aware of it has made me question my relationship both to the world and to writing.

Which is why, as you say, I’ve almost been reading myself back in time, towards something that feels more mystical and ancient. Jenn Ashworth’s brilliant phrase was, I think, ‘replenishing the mulch’ of imagery and ideas, and ever since she said it I think about it constantly. Like, what am I putting in my mulch, what is composting down in there, is it rich enough, is it fertile enough, is it going to sustain another novel or another four novels or, indeed, my inner life, my dream life, all the parts of myself I don’t even give voice to or acknowledge but which fundamentally shape my thought and experience?

Which leads me nicely to Twitter, because that brief conversation with Jenn is a great example of how fantastic social media can still be. You can open yourself up to chance ideas and exchanges, the random, the slightly chaotic, the serendipitous, the tangential, the alternative, and that’s really important to me. The problem is that if you’re not careful, the ‘mulch’ can become exactly the same as everyone else’s – the same books, the same TV shows, the same memes, even the same phrases, all endlessly recirculating and ever more stagnant. So my solution to that is really to go back to a more Magic Mountain conception of time. So long as I’m in touch with all those other strata of time, be it through reading, writing, thinking, meditating or whatever, it’s fine for me to have this thin layer of super-immediate hyper-time over the top. The problem, as with anything, is if it becomes totalising, if it actually erases other modes of time and sources of inspiration.

But I think what we’re getting at here isn’t just a sense of time but also a sense of dominant culture, dominant narratives, and the way that if we’re mindful of what we’re doing, we can use time strategically as an escape route from a kind of assumed consensus. Something I admire hugely about your writing and thought is that I feel you’re never suckered into the overriding discourse, you’re always looking at it critically, and you’re always able, when you need to, to shut out the noise and access what you think. It seems to me that that’s especially true with this book because, as you say above, you’re highlighting ‘the ethical and political risks of making speech the key site of feminist rhetoric about sexual violence’. You’re even making a case for silence, for its value, maybe even its necessity.

Angel:

‘The brilliant at the expense of the true’ God, yes. That’s the risk many writers run, I think. The way the structure of a piece of writing, or its rhythm, its music, can be so seductive even to oneself in the writing of it. It’s something to be so wary of – and that wariness can be paralysing. You might be right that some of my slowness with writing is about this: my suspicion of myself! Feeling seduced by certain ideas out there in the world too, and needing time to weigh them up, gauge my ongoing and changing relationship to them – and then doing the same with what I’m writing. Does it ring true? I love accompanying writers as they figure out what they think. I don’t enjoy just being told what someone thinks, and by extension perhaps what I should think. The mulch is so vital! I love the earthy language you use in thinking about this. I visualise a compost heap! Rot and decay and then growth and flowering – such themes in Come Join Our Disease, right? The cycle of death and creation, and how fruitful and important the rot can be. Patricia Lockwood writes so brilliantly in ‘The Communal Mind’ about that mulch becoming everyone else’s mulch – the way a new subculture in speech on social media could eventually ‘birth a new vernacular – one that the rest of the world at first didn’t understand, and was then seen to be the universal language’. Twitter can be so terrible (but also very funny) in this respect; everyone talking about the same thing! That’s not wholly good for a culture. Like all the Netflix series that seem to be located in no particular place, or rather a kind of amalgam of some kind of Anglo-American suburbia where English-accented kids live in clapboard colonial houses, and the production values homogenise into an algorithm-like smoothness with no bumps or granularity. But I think I’m prone to nostalgia about Twitter; I remember the heyday (for me) was when Kate Zambreno was live-tweeting her reading of Fifty Shades of Grey and it was the smartest, funniest thing I’d read in years; it felt like we were all sitting outside some bar chatting. It’s such a bind: the incidental encountering of thoughts, articles, perspectives that Twitter enables can be truly magical – but it can also be oppressive.

Not just because, if you’re someone who IRL doesn’t really thrive on being constantly surrounded by noise and multiple streams of sound and endless chatter – like living in a bar, basically – then it shouldn’t be a surprise that reproducing that experience within your laptop or your phone is not going to be hugely different. I definitely need a kind of quiet that is incompatible with Twitter.

In Come Join Our Disease, Maya undergoes a kind of journey underworld, doesn’t she? And she shifts from a mandated existence of speech, of social media visibility, to a refusal of all of that. She descends into a realm of silence – and of mulch – of pure bodily existence.

Byers:

That really resonates with me, yes. I feel, like you I think, that speech and silence inform each other, and for me that balance is less about social media than it is all the other things that go with being a writer. With fiction, I’m very often deliberately writing into what I don’t quite know, and finding out what I think and feel as I go, sometimes over the course of several years. With articles and reviews, I feel this pressure to know, and I find myself drawn into an experience of certainty and rapidity that just isn’t there with fiction. I enjoy that at the right time, and I think actually it’s healthy to connect with that certainty when you spend so much time in murkier, more ambiguous territory, but at the wrong moment, it can feel as if it weakens my faith in not knowing, which is where for me fiction is often coming from.

And I think what you say about Maya, and her journey into an underworld, which is absolutely right, is kind of linked to that, because one of the things Maya does in the novel is to radically open herself up to flux. She’s been in this world of rules – be it the formalised and very cruel institutions you have to deal with as a homeless person or the subtler systems of conformity that accompany work, society etc. So she exposes herself, really, to the processes of life those rules and systems are designed to conceal from us, or to allow us to forget: decay and chaos, sickness, entropy, death.

Which of course, as you rightly suggest, is nothing new! Tantric traditions were a huge inspiration there. In both Hinduism and Buddhism there are many examples of practitioners whose spiritual discipline is an engagement with, and embracing of, all those forces. There are people who make their home in cemeteries, people who smear themselves with the ash of cremated bodies and eat rotting meat. Indeed, there’s a Tibetan Buddhist practice where you literally visualise the dismemberment of your own body, so that its pieces can be offered to your demons in order to tame them. The point is that death is simply life’s other face, and there is no way forward without embracing that. Death is simply change. If death is embraced, all change and flux and instability is embraced too, and becomes a source not of fear but of empowerment and understanding.

Obviously though, I must stress that that is not how I live my life at all! I’m just pottering around getting annoyed and anxious about all the same shit as anyone else. And I think that’s what’s truly liberating to me about fiction, but also dangerous. You can live these things without living them. On one hand, that’s very exciting and I think potentially very valuable. On the other hand, much as you can come to convince yourself you’re right, you can come to convince yourself you’ve lived them, which I think is a kind of delusion we all have to guard against.

I’m really interested to ask you what you’re sitting with right now? I think we can’t conclude this conversation without at least alluding to the year that’s just passed, in which we’ve all had no choice but to wait out so much, and be with so much, and attend to ourselves in this really unprecedented way. My personal experience has been that I need to wait out my writing like never before. I wrote a lot last year but I just feel I can’t trust it, because I can’t quite trust anything I’ve felt through the pandemic. I have to put it away, and assess it in the light of a slightly rebalanced world. What’s it been like for you sitting with this book in particular, knowing it was done, but without the closure of actually releasing it, no doubt still following the changes in the culture as you mention above. Is it the book still real for you? Or has it departed? Have you written much over the past year? Or has silence felt more necessary? And speaking just purely as a huge fan and someone who looks forward to all your work, I feel I have to ask: what’s next? Do you know?

Angel:

The rhythms of writing are so weird, aren’t they? I often think about this brilliant moment in The Office (the US version), where Kelly Kapoor (played by Mindy Kaling) is being interviewed for a new role in the office, and is asked about her management skills. The exchange goes something like this: she says ‘I manage a very difficult team, and have shown great initiative in doing so’, and the interviewer says ‘But Kelly, you’re in a team of one, it’s just you’. She replies: ‘I know, exactly – I’m a very difficult person to manage.’ I laughed with such recognition at that, because on the one hand there’s this person who you are who is trying to *make* something, and think across periods, and underneath things and around things, and keep visualising an object or a shape that will contain it all – and on the other hand, there’s this other person who is just dealing with deadlines and cooking dinner and feeling anxious about the pandemic and fighting with a printer that doesn’t work, and you have to somehow manage both these versions of yourself, and at different moments ask what each person wants and needs. Added to that there’s fear about the writing itself, or self-thwarting habits, the things we put in our own way. So it really can feel like managing a fractious team sometimes . . . But perhaps it’s different for you?! I feel that you’re very good at discovering what you need, and really tuning into it – replenishing the mulch. I do it periodically, but the constant dance between silence and speech, activity, busyness, is such a constant source of preoccupation. I wonder how the pandemic affected your writing and working in this respect? The strangeness especially of last spring, the quietness that descended on London . . .

This book does still feel really real and alive to me, even though I did feel, a few months ago, I was really done with it. When MeToo was happening, I initially felt that I *didn’t* want to write about it. I did, eventually – my insistence may have been a clue – but I needed time, to wait out the turmoil in myself about it. I wonder about the pandemic in this respect. I have felt extremely lucky in this whole period. And I also have felt relieved not to be trying to start a whole new project, with the everyday so overwhelming and distracting, and the ground shifting so fast. (Not to mention the Zoom and screen fatigue . . .) I spent most of the last year editing the book and getting it ready for production, and thinking periodically about how the themes in it intersect with the pandemic: how we cope with risk and fear; whether fear must inevitably swamp and crowd out pleasure; what we do with our vulnerability, and whether we can trust others not to abuse our vulnerability or to be indifferent to it. Thinking also about public health narratives, and whether any of the horribly hard-won lessons of the AIDS crisis were truly learnt. But, you know, what I like about having a book out is that, actually, even if you think you’re done with it by the time it comes out, the conversations it leads to ignite it in new ways. I’ve had some conversations just in the last week with people about the book that have made me push my thinking further, or made me newly intrigued by questions within it. There’s always those bits in books where you know you could have written more, or gone in more directions; and I’m actually feeling that strongly at the moment, in a really pleasurable way, because of smart people engaging thoughtfully with it. So it’s a nice feeling, like something that you thought you had put to bed somewhat while fiddling with commas and thinking about who to send proofs to, has come alive again and is wandering around talking to people. As for new projects, I have ongoing, simmering but still slightly inchoate plans for a book about psychoanalysis and the contemporary moment – but I now feel so distracted by the conversations I’m having about this one that I’m hoping it’s just bubbling up somewhere in my mind, and that I can turn to it before too long and feel its pulse.

Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again by Katherine Angel is out with Verso.

Come Join Our Disease by Sam Byers is out with Faber.