1

I woke up. The doorbell was ringing. I looked at the digital clock by my side, the numbers were blinking 05:42.

‘It’s the police,’ I said.

Like all dissidents in this country, I go to bed expecting the ring of the doorbell at dawn.

I knew one day they would come for me. Now they had.

I had even prepared a bag and a set of clothes, so I would be ready for the police raid and what would follow.

A pair of loose black pants in linen, tied with a band inside the waist so there would be no need for a belt, black ankle socks, comfortable, soft sneakers, a light cotton T-shirt and a dark-color shirt to be worn over it.

I put on my ‘raid uniform’ and went to the door.

Through the peephole I could see six policemen on the landing, sporting the vests worn by counterterrorism teams during house raids, the acronym ‘TEM’ stamped in large letters on their chests.

I opened the door.

‘These are search and arrest orders,’ they said as they entered, leaving the door open.

They told me there was a second arrest order for my brother Mehmet Altan, who lived in the same building. A team had waited at his door, but no one answered.

When I asked which number apartment they had gone to, it turned out they had rung the wrong bell.

I phoned Mehmet.

‘We have guests,’ I said. ‘Open the door.’

As I hung up, one of the policemen reached for my phone. ‘I’ll have that,’ he said, and took it.

The six spread out into the apartment and began their search.

Dawn arrived. The sun rose behind the hills with its rays spreading purple, scarlet and lavender waves across the sky, resembling a white rose opening.

A peaceful September morning was stirring, unaffected by what was happening inside my home.

While the policemen searched the apartment, I put the kettle on.

‘Would you like some tea?’ I asked.

They said they would not.

‘It is not a bribe,’ I said, imitating my late father. ‘You can drink some.’

Exactly forty-five years ago, on a morning just like this one, they had raided our house and arrested my father.

My father had asked the police if they would like some coffee. When they declined he laughed and said, ‘It is not a bribe, you can drink some.’

What I was experiencing was not déjà vu. Reality was repeating itself. This country moves through history too slowly for time to go forward, so it folds back on itself instead.

Forty-five years had passed and time had returned to the same morning.

During a morning, which lasted forty-five years, my father had died and I had grown old, but the dawn and the raid were unchanged.

Mehmet appeared at the open door with the smile on his face

I always find reassuring. He was surrounded by policemen.

We said farewell. The police took Mehmet away.

I poured myself tea. I put muesli in a bowl and poured milk over it. I sat in an armchair to drink my tea, eat my muesli and wait for the police to complete their search.

The apartment was quiet.

No sound could be heard other than the police as they moved things around.

They filled thick plastic bags with the two decades-old laptops I had written some of my novels on and therefore could not bring myself to throw away, old-fashioned diskettes that had accumulated over the years and my current laptop.

‘Let’s go,’ they said.

I took the bag, to which I had added a change of underwear and a couple of books.

We left the building. We got into the police car that was waiting at the gate.

I sat there with my bag on my lap. The doors closed on me.

It is said that the dead do not know that they are dead. According to Islamic mythology, once the corpse is placed in the grave and covered with dirt and the funeral crowd has begun to disperse, the dead also tries to get up and go home, only to realize when he hits his head on the coffin lid that he has died.

When the doors closed, my head hit the coffin’s lid.

I could not open the door of that car and get out.

I could not return home.

Never again would I be able to kiss the woman I love, to embrace my kids, to meet with my friends, to walk the streets. I would not have my room to write in, my machine to write with, my library to reach for. I would not be able to listen to a violin concerto or go on a trip or browse in bookstores or buy bread from a bakery or gaze on the sea or an orange tree or smell the scent of flowers, the grass, the rain, the earth. I would not be able to go to a movie theater. I would not be able to eat eggs with sausage or drink a glass of wine or go to a restaurant and order fish. I would not be able to watch the sunrise. I would not be able to call anyone on the phone. No one would be able to call me on the phone. I would not be able to open a door by myself. I would not wake up again in a room with curtains.

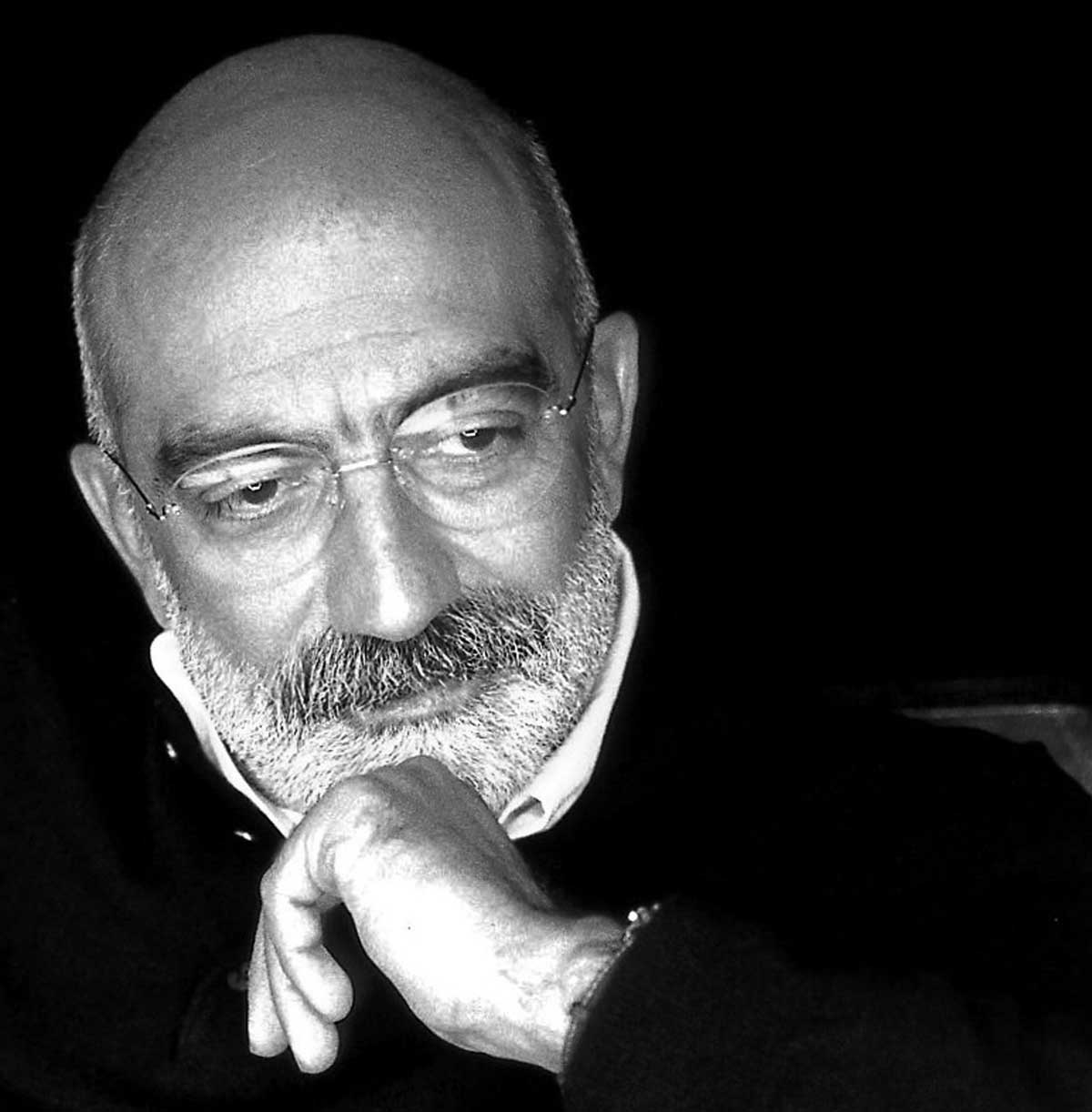

Even my name was about to change.

Ahmet Altan would be erased and replaced with the name on the official certificate, Ahmet Hüsrev Altan.

When they asked for my name I would say ‘Ahmet Hüsrev Altan’. When they asked where I lived I would give them the number of a cell.

From now on others would decide what I did, where I stood, where I slept, what time I got up, what my name was.

I would always be receiving orders: ‘stop’, ‘walk’, ‘enter’, ‘raise your arms’, ‘take off your shoes’, ‘don’t talk’.

The police car was speeding along.

It was the first day of a twelve-day religious holiday. Most people in the city, including the prosecutor who had ordered my arrest, had left on vacation.

The streets were deserted.

The policeman next to me lit a cigarette, then held the pack out to me.

I shook my head no, smiling.

‘I only smoke,’ I said, ‘when I am nervous.’

Who knows where this sentence came from. Nowhere in my mind had I chosen to make such a declaration. It was a sentence that put an unbridgeable distance between itself and reality. It ignored reality, ridiculed it, even as I was being transformed into a pitiful bug who could not even open the door of the car he was in, who had lost his right to decide his own future, whose very name was being changed; a bug entangled in the web of a poisonous spider.

It was as if someone inside me, a person whom I could not exactly call ‘I’ but nevertheless spoke with my voice, through my mouth, and was therefore a part of me, said, as he was being transported in a police car to an iron cage, that he only smoked when he was ‘nervous’.

That single sentence suddenly changed everything.

It divided reality in two, like a samurai sword that in a single movement cuts through a silk scarf thrown up in the air.

On one side of this reality was a body made of flesh, bone, blood, muscle and nerve that was trapped. On the other side was a mind that did not care about and made fun of what would happen to that body, a mind that looked from above at what was happening and what was yet to happen, that believed itself untouchable and was, therefore, untouchable.

I was like Julius Caesar, who, as soon as he was informed that a large Gallic army was on its way to relieve the siege at Alesia, had two high walls built: one around the hill fort to prevent those inside from leaving and one around his troops to prevent those outside from entering.

My two high walls were built with a single sentence to prevent the mortal threats from entering, and the worries accumulating in the deep corners of my mind from exiting, so that the two could not unite to crush me with fear and terror.

I realized once more that when you are faced with a reality that can turn your life upside down, that same sorry reality will sweep you away like a wild flood only if you submit and act as it expects.

As someone who has been thrown into the dirty, swelling waves of reality, I can comfortably say that the victims of reality are those so-called smart people who believe that you have to act in accordance with it.

There are certain actions and words that are demanded by the events, dangers and realities that surround you. Once you refuse to play the assigned role, instead doing and saying the unexpected, reality itself is taken aback; it hits against the rebellious jetties of your mind and breaks into pieces. You then gain the power to collect the fragments and to create from them a new reality in the mind’s safe harbors.

The trick is to do the unexpected, to say the unexpected. Once you can make light of the lance of destiny pointing at your body, you can cheerfully eat the cherries you had filled your hat with, like the unforgettable lieutenant in Pushkin’s story ‘The Shot’, who does exactly that with a gun pointing at his heart.

Like Borges, you can answer the mugger who asks, ‘Your money or your life?’ with, ‘My life.’

The power you will gain is limitless.

I still don’t know how I came to utter the sentence that transformed everything that was happening to me and my perception of it, nor what its mystical source might be. What I know is that someone in the police car, who was able to say he smoked only when he was nervous, is hidden inside me.

He is made of many voices, laughs, paragraphs, sentences and pain.

Had I not seen my father smile as he was taken away in a police car forty-five years ago; had I not heard from him that the envoy of Carthage, when threatened with torture, put his hand in the embers; had I not known that Seneca consoled his friends as he sat in a bathtub of hot water and slit his wrists on Nero’s orders; had I not read that on the eve of the day he was to be guillotined, Saint-Just had written in a letter, ‘The conditions were difficult only for those who resisted entering the grave,’ and that Epictetus had said, ‘When our bodies are enslaved our minds can remain free’; had I not learned that Boethius wrote his famous book in a cell awaiting death, I would have been afraid of the reality that surrounded me in that police car. I would not have found the strength to ridicule and shred it into pieces. Nor would I have been able to utter the sentence with a secret laughter that rose from my lungs to my lips. No, I would have cowered with worry.

But someone, whom I reckon to be made from the illuminated shadows of those magnificent dead reflected in me, spoke and thus managed to change all that was happening.

Reality could not conquer me.

Instead, I conquered reality.

In that police car, speeding down the sunlit streets, I set the bag that was on my lap onto the floor with a sense of ease and leaned back.

When we arrived at the Security Department, the car drove through a very large gate into the building and started down a winding road. As we descended there was less and less light and the darkness deepened.

At a turn in the road, the car stopped and we got out. We walked through a door into a large underground hall.

This was an underworld completely unknown to the people circulating above. It reeked of stone, sweat and damp. It tore from the world all those who passed through its dirty yellow walls, which resembled a forest of sulfur.

In the drab raw light of the naked lamps, every face bore the wax dullness of death.

Plain-clothes policemen waited to greet us creatures torn away from the world. Past them, a hallway led deeper inside. Piled at the base of the walls were plastic bags that looked like the shapeless belongings of the shipwrecked swept ashore.

The policemen removed the tie from around the waist of my trousers, my watch and my ID.

Here in the depths without light, the police, with each of their gestures and words, carved us out of life like a rotten, maggot-laced piece from a pear and severed us from the world of ‘the living’.

I followed a policeman into the hallway, dragging my feet in my laceless shoes. He opened an iron door and we entered a narrow corridor where an oppressive heat grasped you like the claws of

a wild beast.

A row of cells with iron bars ran along the corridor. Each cell was congested with people. They lay on the floor. With their beards growing long, their eyes tired, their feet bare and their bodies coated in sweat, they had melted the boundaries of their existence and become a moving mass of flesh.

They stared with curiosity and unease.

The policeman put me in a cell and locked the door behind me.

I took off my shoes and lay down like the others. In that small cell filled with people lying down, there was no room to stand.

In a matter of hours I had traveled across five centuries to arrive at the dungeons of the Inquisition.

I smiled at the policeman who was standing outside my cell, watching me.

Viewed from outside I was one old, white-bearded Ahmet Hüsrev Altan lying down in an airless, lightless iron cage.

But this was only the reality of those who locked me up. I had changed it.

I was the lieutenant happily eating cherries with a gun pointing at his heart. I was Borges telling the mugger to take his life. I was Caesar building walls around Alesia.

I only smoke when I’m nervous.

2

I nodded off for a moment. When I opened my eyes I saw that the staff colonel on the cot across from me and the submarine colonel curled up on a sheet of plastic on the floor were both asleep.

The young village teacher who had been told to sell out his friends laid his prayer rug between two cots and began his devotions.

In the dim light of the cell I could see his figure – a dark shadow – prostrating himself on the rug.

I had not slept for nearly twenty-four hours and I was exhausted. My bones ached.

The long black shadows of the iron bars cut through our chests, our faces, our legs and divided us into pieces.

The bare feet of the colonels shone in the cold light seeping in from the corridor, like pieces of white rock.

The colonel across from me groaned in his sleep.

I was in a cage.

In the damp dimness, in the shadows of the iron bars that cut into this dimness, in the young schoolteacher’s murmurs of prayer, in the shiny stone-like feet of the colonels, in the moans that came from across the cell, in all of these, there was something more startling than death, something that resembled the empty space between life and death, a no-man’s-hollow which reached neither state.

We were lost in that hollow.

No one could hear our voices. Nobody could help us.

I looked at the walls. It was as if they were coming closer.

Suddenly, I had this feeling that the walls would close in on us, crush and swallow us like carnivorous plants.

I swallowed and heard a groaning noise escape from my throat.

Something was happening.

I felt an army of ghosts stir within me. It was as if that famous army of terracotta warriors, which the Chinese emperor had built to guard his body after death, was coming alive inside me. Each carried with him a different fear, a different horror.

I sat up and leaned my back against the wall.

The heat was brushing my face like a furry animal. My forehead was sweating. I was having difficulty breathing.

This place was so narrow, airless. I wouldn’t be able to stay here.

For a moment, I had an irresistible urge to get up, hold the iron bars and shout, ‘Let me out of here. Let me out of here, I am suffocating.’

With horror I realized I was lurching forward.

I clenched my fists as if to stop myself.

I knew that with a single scream I would lose my past and my future, everything I had, but the urge to get myself out of that cage with its walls closing in on me was irresistible.

The terrifying urge to shout and the pressure of knowing that this shout would destroy my whole life were like two mountains colliding and crushing me in between.

My insides were cracking.

The young teacher stood up and put his hands together on his belly; the colonel across from me groaned and turned over to his other side.

I tucked in my legs and put my arms around my knees.

My vision was getting blurry, the walls were moving.

I wanted to get out of here, I wanted to get out right away and knowing this was impossible made my brain feel like it had pins and needles, as if thousands of ants were crawling in its folds.

The realization that I was about to embarrass myself intensified my fear even more.

I saw two eyes. Two eyes with a cold, cruel, almost hostile look in them, shiny as glass, like the eyes of a wolf chasing his prey in a rustling forest. Those eyes were inside me, keeping watch on my every move.

I had survived such moments in my youth, moments when one wanders to the edge of madness. I knew I had to turn back. If I took another step, I would cross the line of no return.

My lungs were rising up to my throat, blocking my windpipe.

The young teacher had again prostrated himself on the prayer rug.

He was muttering a prayer.

He, too, was begging to be saved.

The colonel lying on the floor groaned in his sleep.

I took a deep breath to push my lungs back down. I took a gulp of warm water from the plastic bottle I had by my side.

I thought of death.

Instinctively, I was trying to hold on to the idea of death. The eternity of death has the power to trivialize even the most terrifying moments of life.

Thinking that I would die had a calming effect on me. A person who is going to die does not need to fear the things that life presents.

Like everyone else, I was insignificant, what I had been living through was insignificant, this cage, too, was insignificant, the distress that suffocated me was insignificant and so too was the evil I had met.

I clung firmly to my own death. It calmed me.

The teacher saluted the angels, turning his head first to the right, then to the left, and finished praying.

He turned around and looked at me.

Our eyes met.

A shy smile appeared on his face as if he was embarrassed – although about what I don’t know.

Moving with difficulty between the two cots, he turned to lie down beside the colonel on the plastic-covered rubber that lay on the floor.

His bare feet now shone alongside those of the colonel.

The shadow of an iron bar cut through his ankles like a black razor. I saw two feet attached to nothing.

I was going to die one day.

What I was living through was insignificant.

The eyes inside me were shut. The wolf was gone.

I wasn’t going to lose my mind.

During a scorching heat, when crops catch fire, a circle is drawn around the blaze and the grain along that circle is set alight before the flames can reach it. Once the fire arrives at the circle it stops, as there is nothing left there to burn. They use fire to put out fire.

I had surrounded and extinguished the fire of terror, which life had lit in a cage, with the fire of death.

I knew that my life from now on would be a series of opposing fires. I would surround those started by my jailers with the fires of my mind.

Sometimes death will be the source; sometimes the stories I write in my mind; sometimes the pride that won’t let me leave behind a name stained by cowardice; sometimes it will be the desires of the flesh releasing the wildest fantasies; sometimes peaceful reveries; sometimes the schizophrenia unique to writers who twist and tweak the truth in their red-hot hands to create new truths; sometimes it will be hope.

My life will pass fighting invisible battles between two walls; I will survive by hanging on to the branches of my own mind, at the very edge of the abyss, and not by giving in to the disorienting inebriety of weakness, even for a moment.

I had seen the monstrous face of reality.

From now on I would live like a man clinging to a single branch.

I didn’t have the right to be scared or depressed or terrified for a single moment; nor to give in to the desire to be saved, to have a moment of madness, nor to surrender to any of these all-too-human weaknesses.

A momentary weakness would destroy my entire past and future – my very being.

If I were to tire and let go of the branch I was holding, it would be fatal; I would fall to the bottom of the abyss and become a mess of blood and bones.

Would I be able to endure the days, weeks, months and years of swinging in the air, unable to let go of the branch for even an instant?

If I were to let go and break into pieces in the abyss of weakness, I would lose not only my past and future but also the strength that enables me to write.

Because the prospect of being cut off from the precious lode of writing scared me more than anything, that fear would suppress all other fears and give me the ability to endure. Courage would be born of fear.

Now that the fear of losing my mind, which had momentarily licked my insides, and the heavy feeling of suffocation distress had passed, a tense fatigue took hold of my body.

The teacher, too, was fast asleep. The restless movements of those feet cut off from the ankles had stopped.

Though tired enough to pass out, I couldn’t sleep. It was as if even sleep itself was too exhausted to come and take me.

When the police took me from my apartment, I threw in my bag a book I had recently ordered on medieval Christian philosophers, thinking it would have entertaining and diverting stories about their lives.

To escape what I was living through, to rest and relax a little, I would take refuge in what they had endured.

These philosophers struggled to resolve the secrets of their personal lives while still daring to unravel the mysteries of the universe. They experienced an innocent helplessness before the question ‘What is life?’, even though they had written thousands of pages on the subject. This, it had always seemed to me, was an amusing summary of the human condition.

In that dim light, as my cage-mates moaned and groaned, I opened the book.

I had hoped reading would calm me and put me to sleep. I was wrong.

The book did not consist of entertaining biographies. Instead, it recounted the philosophers’ rather compelling views.

And St Augustine, of course, was the first one to greet me.

This bear of a man prays sincerely to be rid of the burden of sexuality, yet begs God not to do it quickly because he is having a good time. He persists in trying to find a reasonable explanation for why God, being ‘absolutely good’, would create such grave evil. Augustine wakens in me a sense of tenderness that contrasts with his stature and significance.

I began to read.

That a man locked in a cage would find himself with no alternative other than to read about why God created evil seems part of life’s unfathomable facetiousness.

This time, reading Augustine angered me. He says that God had reason to create torture, persecution, sorrow, murder and the cage they locked me up in along with the men who locked me up in it: all this evil, says Augustine, was the result of Adam acting with ‘free will’ and eating the apple.

I was in a cage because a man had eaten an apple.

The man who ate the apple was God’s own Adam, made by his own hands; the man who was locked in the cage was me.

And Augustine was asking me to be thankful for this?

I grumbled as if he stood before me, shoddily dressed, with his big balding head, long beard and charming smile.

‘Tell me,’ I said, ‘what is the bigger sin – a man eating an apple or punishing all of humanity with torture because a man ate an apple?’

I added furiously, ‘Your God is a sinner.’

The colonel across from me turned to his side, groaning; the shadow of the bar cut off half his face.

‘I am paying for your God’s sins.’

My eyes were burning from fatigue, from lack of sleep. A stupor-like slumber was dragging me down.

The colonel across the room moaned.

I looked up and saw that he was awake and crying.

While he was in jail, his three-year-old child was in the hospital, grappling with death.

I turned and faced the wall so he wouldn’t know I had seen him cry.

I was never going to let the branch go. Not even for a moment.

As I fell asleep I thought of that little girl, grappling with death.

‘Is an apple worth all of this?’ I thought.

3

Each cell in the prison has a stone courtyard in front of it that is six steps long and four steps wide, with an iron drain in the middle for rainwater.

The high walls of the courtyard have barbed wire on them. A steel cage covers the top.

To use the title of the novel my father wrote in prison, ‘a handful of sky’ is what you see when you look up, but even that is divided into the small squares of the steel cage above.

When spring arrives, migratory birds fly in through the cage and make nests on the barbed wire.

The inmates pacing in their adjacent courtyards don’t see each other but they can talk by shouting. We recognize one another from our voices.

On occasion, my young cellmate Selman chats with our neighbors we have never seen.

What they talk about doesn’t matter.

What matters is knowing there are people present beyond your cell walls and letting them know of your existence.

For us, the world is the neighboring courtyards that our voices can reach. Shouting is our way of communicating with the world.

One spring day, Selman was talking to the voice in the courtyard next to ours.

‘The birds have started migrating here,’ Selman said.

‘I am looking after a parakeet,’ the voice answered. ‘He was born in the prison, then his mama died. I raised him.’

‘I never saw your parakeet flying about,’ said Selman. ‘I guess I am never there at the right time.’

‘He doesn’t fly,’ said the voice in the next courtyard.

Then, with the compassion of a father feeling sorrow for a child, the voice added: ‘He is afraid of the sky.’

All images courtesy of the author