Anna Wharton:

The moment I saw you explaining what your life was like with dementia, in a video you’d recorded for a charity, I knew that I wanted to ghost a book about what it was like to look at the world through your eyes. As a ghostwriter I enjoy taking on different voices – it’s like being an actor assuming different roles. But I also want to write books that will change how people think about a certain subject. I approached you, and together we decided to write the book which became your memoir, Somebody I Used to Know. Usually when I work as a ghostwriter, I rely heavily on my subject’s memory, so this posed a huge challenge, as you ‘had no memory’. Luckily you started a blog about two months after you were diagnosed with dementia, in July of 2014. This was just a few lines at the start, a little about what you did each day, but it gave me a timeline to follow. How much can you remember about our writing process?

Wendy Mitchell:

Well, what I do remember is how we had to find a different way of working, because I can’t use the phone anymore, it’s too disorientating, and we live at opposite ends of the country. We had to use WhatsApp and email as our main means of communicating, then you would write and send me chunks to read.

Anna Wharton:

Yes, it’s incredible to think this book was mostly written over WhatsApp. It was less of a problem for me as I had previously ghosted another book by an author who is deaf and blind, and we also lived at opposite ends of the country. We ended up doing all of our interviews face to face. There is no one-size-fits-all approach when you’re ghostwriting, you need to work with the individual and work out how they best work and what will make them most comfortable.

Wendy Mitchell:

I remember we also discovered a gap of eighteen months before I was diagnosed and before my blog started where I had no idea what happened or when. We had to piece a timeline together from hospital notes and my daughter Sarah’s diary.

Anna Wharton:

It was much easier for me to write after you started your blog. I remember reading through every single one of your posts (I think there were about 150,000 words), and that gave me a timeframe of what you had been doing and when, but that’s all it was at that point. You didn’t write with any emotion or colour at that time in your life, because the blog was only meant to be a record of what you had done that day.

Wendy Mitchell:

Oh yes, you taught me so much about ‘detail’ and its importance in writing. I was saying somewhere recently how much you improved my writing skills.

I also remember how patient you were with me, as I could never remember what we’d already written, and would say: ‘we must include this’, and you’d patiently say: ‘we did that last week’.

There were some things which were hard for me to talk about – particularly euthanasia. I remember your expression in your WhatsApp messages, you’d say: ‘You know I’m going to probe today . . .’ I felt I needed to talk to my daughters about some issues, like euthanasia, before I spoke to you, otherwise it didn’t feel right. It was also quite exposing for them to rake over the whole of my life, particularly my life with them as a single mother.

Wendy Mitchell and Anna Wharton

Anna Wharton:

In some ways writing the book opened up those conversations for you. There were other things you didn’t feel comfortable talking about at first – I remember you telling me you couldn’t talk about the ‘you’ before dementia because you were a private person. I thought: ‘Hmm, we’ll see about that.’ I felt strongly that people needed to know the person you were as well as the person you are now.

Wendy Mitchell:

Oh did I say that? Maybe that was the old me putting her foot down against this new ‘warts and all’ me.

Anna Wharton:

I think when being ghost-written it’s difficult for authors to conceptualise the book. I developed an idea of how it would work, and you just had to trust me. The concept of the split narratives, which we used – the first and second person – came to me over the course of a couple of months. I always liken this process – of trying to find the right way to tell a story – as having a tangled ball of wool and searching for the loose end in order to know where to start.

Wendy Mitchell:

It was always a case of ‘you know best’. I trust very few people. I trust a handful of people including yourself, but I have to rely on other people in a different way now – for example if someone tells me we’ve met before, I won’t have any idea. I rely on intuition a lot more these days.

I remember how I looked forward to our daily pings of WhatsApp messages, and how sad it felt towards the end of the book, when I began thinking that we were near the end of our time working together.

Anna Wharton:

Yes, the ghostwriter and the author can build such a close relationship. We spoke on email every day, sometimes for hours. I remember that you were afraid of that relationship coming to an end, but I always promised I wouldn’t ‘let go of your hand’. It works both ways – I miss my authors too when we finish working so intensively together.

There were some days of course when the fog came down in your brain and we simply had to wait for it to lift. Once you wrote what it was like as you came out of the fog, and it was such a fascinating passage that I literally just copied and pasted into the book:

I wake. It’s still light. Where have I been? The sun is shining into my room, but the duvet is pulled up to my chin. I’m hot and, I realise, fully clothed. I push the duvet from me and lie there, still. I hear music on the radio, but I don’t recognise the song. It’s a few more moments before I turn to the clock beside my bed: 3.25 pm, Monday, 10 April 2017. How long have I been here? When did the fog come down? There is a man speaking – the DJ from the radio. I try to catch his words as they float around the room like butterflies. I pin one, then another and another. It’s Steve Wright. A familiar voice. I’m coming back.

Wendy Mitchell:

I suppose you just had to write around my foggy days, but it must have been annoying to keep waiting for the fog to clear.

Anna Wharton:

I completely understood. You talk in interviews about how you can’t remember what’s in the book, but you read every section and approved it before we moved on. Sometimes the process of writing the book would ‘recover’ memories you thought you’d lost, and you’d write notes to yourself in your sleep and send me pictures of them on WhatsApp saying: ‘Does this mean anything to you?’ and I would reply: ‘Yes, we were talking about that yesterday.’ I always liked the idea that writing the book returned memories to you . . .

Wendy Mitchell:

Yes, that was strange. That writer in the night filling in the Post-It notes while I slept. I still couldn’t tell you what’s in my book. But if you read me a piece I would instantly know that it was me.

Anna Wharton:

Your memory wasn’t always reliable. On some days I’d get slightly different versions of the same event from you, but rather than finding this frustrating, I enjoyed it – it helped me to colour in the picture a little more. Sometimes we’d go over scenes or memories numerous times in order to layer up enough detail for the book.

Wendy Mitchell:

Hopefully I didn’t give you totally different stories though? I get a lot out of images, and they often help me to remember certain things. I remember it hitting me one day – how concerned I was for my daughters, because the book obviously talks about their lives growing up. This was simply my version of events, not theirs. I think in that way, everyone’s memory is unreliable.

Didn’t I remind you of something one day? Now I’ve said that I’ve got this image of our emails suddenly going quiet . . .

Anna Wharton:

That’s my favourite story. I sat down to write one day, and I messaged you a question and you responded, reminding me I was meant to be at my osteopath appointment. I had completely forgotten!

Wendy Mitchell:

That must have been it! I would have looked back at our old WhatsApp messages to remind myself of what we’d last spoken about.

Anna Wharton:

I know you do that a lot – look over the last conversations you’ve had with people so that you remember to ask about anything they mentioned they were upset about, or excited about. That’s why you are such a brilliant friend – you don’t let dementia steal anything from you. Whenever people ask me what you are like, I always describe a swan, gliding through life, her legs working frantically beneath the surface, and I know that each day they have to work harder – even though you make it look easy. I don’t think I’ve told you that before, but that’s how I think of you . . .

Wendy Mitchell:

That’s the perfect description. That’s why this book is the whole me. I give this impression at events of a smiley, happy version of myself because I’m pleased to be there, but people don’t know how hard it is for me to get to each event, and the banging headache I’ll have for days afterwards. But my book shows every side of me.

Anna Wharton:

We always wanted to write a book not just about dementia, but about how to live life in the face of adversity. In that way this is a book for everyone.

Wendy Mitchell:

Yes, I wanted to show how the glass half full personality and previous skills and characteristics have helped me cope, and I hope that’s what we’ve achieved.

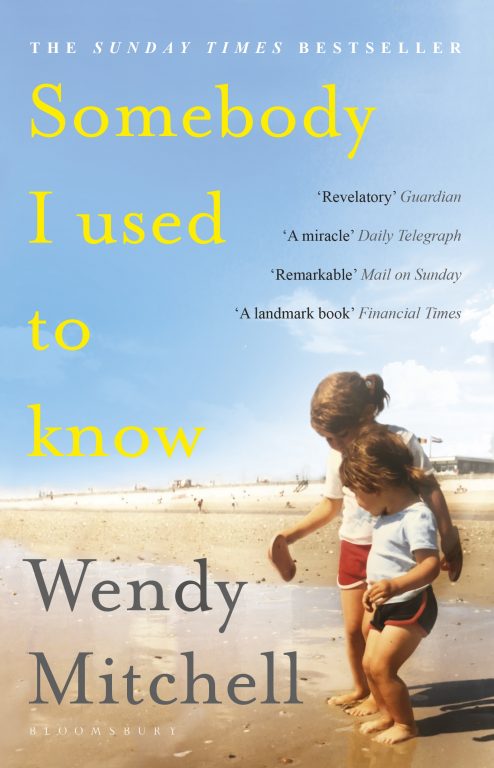

Wendy Mitchell’s Somebody I Used to Know is available now from Bloomsbury Publishing.

Image © Shannon Kringen