From a distance, the map of the forecourt of Hollywood’s famous Chinese Theatre looks a lot like a county map of Iowa or Pennsylvania, but when you get closer, you see that instead of Pottawattamie or Lancaster or Osceola, the squares contain the names of movie stars. West of the entrance to the picture palace are the handprints and footprints and signatures of American royalty like Danny Kaye and Irene Dunne (two of my favorites), along with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers (among my grandmother’s favorites); east are Humphrey Bogart and Meryl Streep. Bookending the box office are Harrison Ford and the cast of Star Trek.

A portion of the Forecourt of the Stars, otherwise known as ‘The Floor of Fame’, Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, California, USA

I live in Los Angeles now, but I can’t say I understand it yet. Sprawling, rising and falling, sweltering in the San Fernando Valley and often chilly on the coast, flaunting palm trees against a backdrop of increasingly fire-prone chaparral, rife with both hardship and privilege, Los Angeles is lived not only in English and Spanish, but also in Armenian, Persian, Russian, Korean, Tagalog, Chinese. The skies of my neighborhood are frequented by hummingbirds patrolling the California fuchsia and deafening LAPD helicopters scanning the streets for the perpetrators of more and more violent crimes. A couple of days ago, a few blocks away, a man was shot and killed outside an Urban Outfitters at noon.

High school, Pasadena, California, USA

‘The season’s Greetings’

Postmarked 23 December 1906

One thing that helps me to cope is to look down. Not only at the forecourt of the Chinese Theatre, but everywhere. I like to look at all of the inscriptions in the city’s sidewalks done by ordinary Angelenos, non-stars whose lives are recorded in streaks underfoot: dates and initials, declarations of neighborhood pride, religious belief, love and political conviction – comments made on wet cement that act as concrete reminders that this and every place is many places, countless individual objects and organisms coming into contact, undergoing transformations, fusing, richly clashing, breaking apart. The graffiti of Los Angeles enable me to grapple with my surroundings much as postcards always have.

Omaha, Nebraska, USA

‘Vi vänta att få höra från Mrs. Wam’, ‘We are waiting to hear from Mrs. Wam’

Postmark torn, but dated by the author 17 March 1908

The word ‘graffiti’ first appeared in English in 1859, in an anonymous piece for the Edinburgh Review titled ‘The Graffiti of Pompeii’. The article lists examples ranging from humdrum to spectacular. Together, this ‘motley’ collection creates the kind of day-to-day portraiture that artworks intended to portray specific people at specific times in specific places nonetheless rarely achieve. Here, neither creator nor subject takes the trouble to pose, since graffiti are just ‘scribblings’, unlikely to last, although of course they have lasted, along with innumerable other examples: epigrams by ancient Roman women poets on the legs of the Colossi of Memnon; in Jordan, Nabataean signatures; in Saudi Arabia, eighth-century pleas for forgiveness; twentieth-century slogans of political protest in Santiago de Chile and Buenos Aires; in Managua, lines by Ernesto Cardenal. Spanning millennia and continents, graffiti are the emphatic traces of our travels in space and time. No matter what they say, they always communicate a particular person’s presence in a particular place at a particular moment, the impact they made on their era and location and the effect their circumstances had on them. In a way, graffiti always say: ‘I was here.’

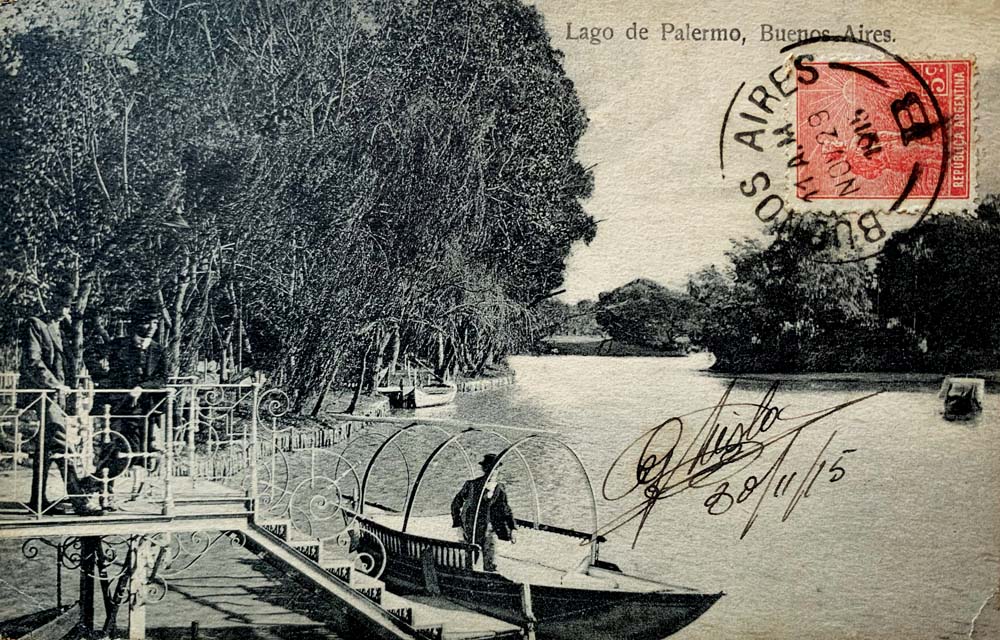

Lago de Palermo, Buenos Aires, Argentina

‘Signature, 30/11/15’

Postmarked 11 a.m., 29 November 1915

Six years after the Edinburgh Review ushered the word ‘graffiti’ into English, a Prussian postal worker named Heinrich von Stephan advocated for the official introduction of an innovative new communication technology that would come to be known as the postcard. Stephan believed in enabling everyone to communicate with everyone else, no matter the distance, and he would go on to establish the Universal Postal Union, which completely transformed the interactions of citizens of different countries. He also made Germany’s first phone call (fittingly, from the post office to the telegraph office in Berlin). In 1865, however, the idea of a cheap postcard that would keep messages short and sweet while also exposing them to anyone’s gaze was deemed indecent by the German Post Association, and Stephan’s proposal was rejected.

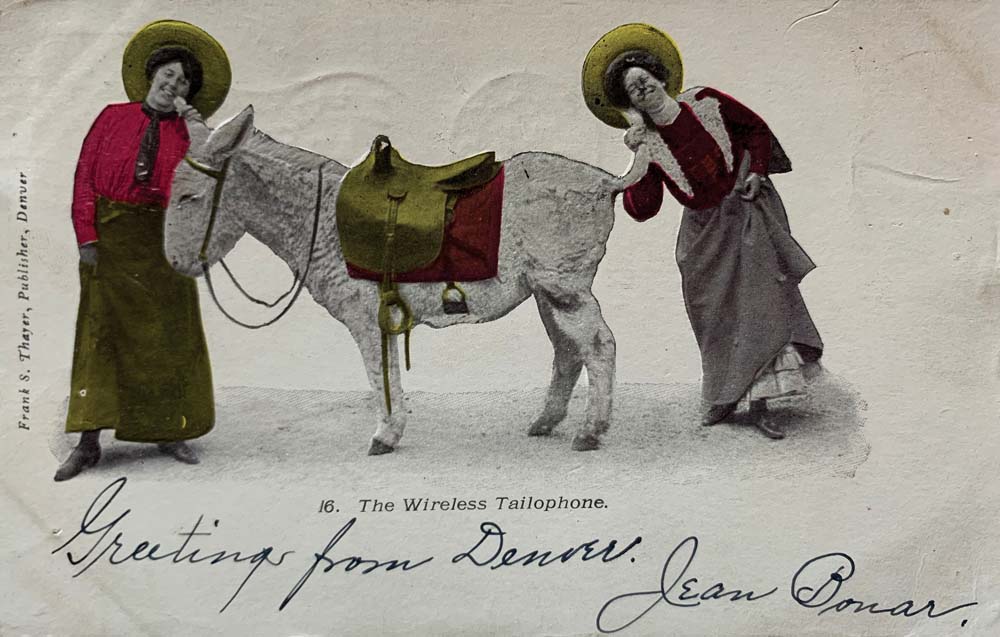

The Wireless Tailophone, Denver, Colorado, USA

‘Greetings from Denver. Jean Bonar’

Postmarked 7 a.m., 19 July 1907

Soon after I arrived in California, I met a gentle man named Francisco who told me how he rose to graffiti stardom in the 90s in LA, until the police caught wind of his work and launched a massive manhunt. He spent about three months going from house to house, trying to evade the authorities, until finally, exhausted, he decided to move to Chicago, where he had relatives. He went to his mom’s house to spend his last night in LA with her; at 7 a.m. the next morning, his mom’s house was surrounded by cops. He told me he tried to run away from them; I asked him if he wasn’t afraid of getting shot. He said he just wasn’t thinking in the moment, but that they had all had their guns drawn. He was in jail, he said, ‘for a while’.

While early postcard publishers may not have faced brushes with death at the hands of law enforcement, the undermining of traditional etiquette did provoke widespread concern and even outrage. Conceived as the first truly democratic form of communication, might not postcards make threadbare the very fabric of society by offering the masses access to the epistolary institutions of the aristocracy? And yet, in 1869, Austrian economist Emanuel Herrmann made a similar suggestion to Stephan’s in the Neue Freie Presse; his idea was taken up, and from Austria the postcard spread with astonishing rapidity around the world. ‘During the first six months of 1898,’ write Lynda Klich and Benjamin Weiss, ‘Germans mailed over twelve million postcards; not even four years later, they were sending almost that number in a single week.’ In 1905, there were over 4,000 postcard shops in Tokyo alone. ‘In 1909 the British postal service sold 833 million stamps for postcards, nearly twenty for every man, woman, and child in the United Kingdom.’

The United States was a relatively late adopter of the postcard, but when the event occurred, Americans embraced the modern medium at least as wholeheartedly as their Old World counterparts. ‘Sold in virtually every five-and-dime store, news-stand, and hotel from Brooklyn to Bakersfield,’ writes Jeff Rosenheim, ‘postcards satisfied the country’s need for human connection in the age of the railroad and the Model T when, for the first time, many Americans regularly found themselves traveling far from home.’

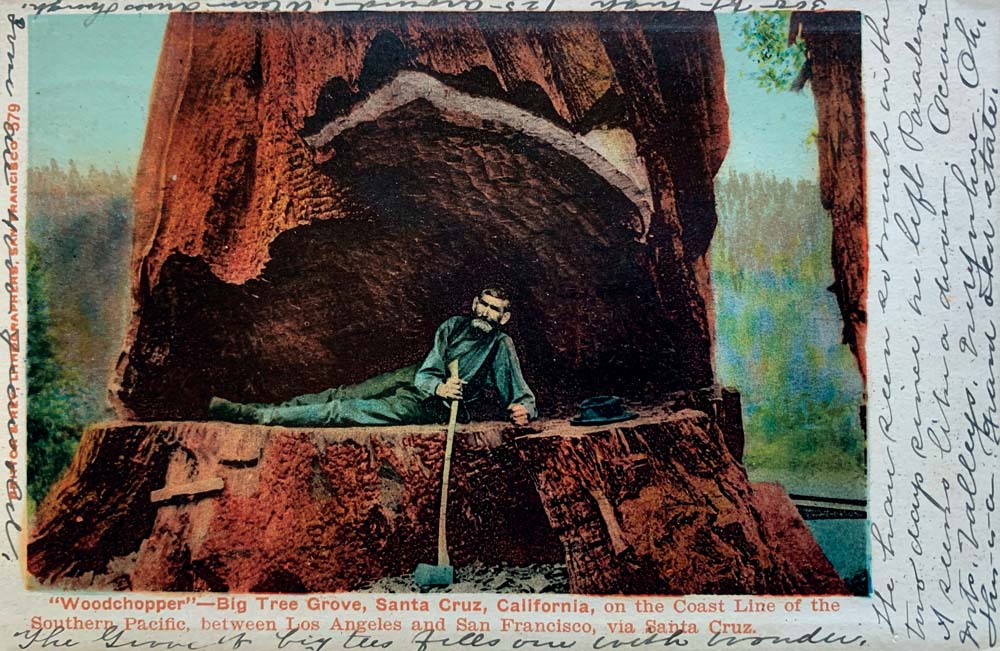

Woodchopper, Big Tree Grove, Santa Cruz, California, USA

‘The grove of big trees fills one with wonder. We have seen so much in two days since we left Pasadena it seems like a dream. Ocean into valleys. Everywhere Ok. This is a grand old state. 300 ft high 125 around. A tram drives through. Some are 4000 years old.’

Postmarked 6.30 a.m., 12 April 1906

Initially, postcards featured an image on one side and space for an address on the other. No other writing was permitted on the address side, meaning that any messages from sender to recipient had to fit within the picture itself, or else the white border that was in widespread use during this period. This changed in Great Britain in 1902 and in the United States in 1907. Following the introduction of the ‘divided back’, fewer messages were inscribed on the images of the postcards, though there remain those correspondents who prefer to foreground their ‘graffiti mobili’, even to this day.

Sign in to Granta.com.