1

Lying half-asleep in my room at the Holiday Inn one night I listened to a song I hadn’t heard in twenty years. The tune was ‘Marching Through Georgia’, but the words did not belong to the American Civil War. I last heard them rising from the crowd at the Glasgow Rangers football ground, where every alternate Saturday the chant is probably bellowed still:

Hello, hello, we are the Billy Boys!

Hello, hello, we are the Billy Boys!

We’re up to our knees in Fenian blood,

Surrender or you’ll die,

For we are the Brigton Billy Boys.

I went to the window. Members of the British popular press were walking unsteadily towards the hotel. Great drinkers and pranksters, these chaps from the tabloids. Already in Gibraltar we’d enjoyed a fortnight of jokes. The first fashion was for water pistols, which to be strictly accurate was started by the men of Independent Television News (or at least it started at their party, shortly before their guests were thrown into the swimming pool). You might be sitting innocently in a bar or walking down the street when the challenge came from behind, ‘Stop, police, hands up!’ and you’d turn sharply – very much, I imagine, as Danny McCann and Mairead Farrell turned – and receive a small jet of water straight in the chest. This was the English journalists’ reconstruction of the role of the Special Air Service Regiment as executioners of the members of the Irish Republican Army. The role of the Irish Republican Army itself had to wait for the second fashionable joke. A couple of Japanese transmitter-receivers were purchased – the kind of thing strolling British policemen use, the kind of thing we’d been shown in court as an IRA bomb-detonating device – and then demonstrated whenever an evening looked as though it might close unpromisingly in an exchange of civilities. Once, at the Marina, I came across a drunken couple shouting into these machines outside a quayside restaurant. ‘Shitbag calling fuckface, shitbag calling fuckface, are you receiving me, over?’ ‘Fuckface to shitbag, fuckface to shitbag, I am receiving you, over . . . ’ And now, two weeks into the inquest into the killings of three Irish republicans, this Orange song rolled around the lanes of Gibraltar at one in the morning. ‘Hello, hello, we are the Billy Boys . . . up to our knees in Fenian blood.’ The only surprise was that Englishmen seemed to know some of the words of a song born of sectarian gang-fighting in Glasgow of the 1930s. But then the English these days are a surprising race.

I write as a Scot, and one with too much of the Protestant in him ever to empathize much with the more recent traditions of Irish republicanism, as well as an ordinary level of human feeling which precludes understanding of the average IRA bomber. But the longer I spent in Gibraltar, the more difficult it became to prop up a shaky old structure – that lingering belief in what must, for lack of a more exact phrase, be called the virtues of Britishness. Both the inquest and its setting played a part in this undermining; perhaps this is what the British government meant when it said that it feared ‘the propaganda consequences’ of such an inquiry and set up an informal cabinet sub-committee (which included Mrs Thatcher) to combat the eventuality. As it turned out – and who knows what part the informal committee played – the government need not have worried. They got the verdict they wanted, the great mass of British public opinion applauded it and the proceedings were minimally covered in the only foreign media which matter to Britain, which lie in New York and Washington. The government then pressed ahead with ‘the war to defeat the terrorist’ by banning IRA spokesmen and their political sympathizers from radio and television, where in any case they had scarcely ever appeared, and renewed attacks on the television programme that had ventured to suggest that the Gibraltar killings raised questions which needed proper investigation.

And that, so far as the British government was concerned, closed the Gibraltar affair. One or two journalists remained sceptical, but a week after the verdict the topic had vanished even from the letters columns.

What is Gibraltar? John D. Stewart, in the only decent book about the place, wrote that

it may symbolize steadfastness to some and arrogance to others, the British bandit or the British policeman, according to the point of view. But the strongest of all the Rock’s suggestions . . . is that concept which used to be called Military Glory, and which we have come to reassess as the slaughter of young men for causes vaguely understood and rapidly discredited and cast aside.

Stewart wrote that more than twenty years ago. Since then Northern Ireland and the Falklands War have intervened to recast the military’s position in British life, and the disparaging reassessment of ‘military glory’ which seemed so enduring to Stewart in 1967 has now itself been reassessed. Who, in 1967, had heard of the Special Air Service Regiment? Who could imagine that in less than two decades its initials, SAS, would comprise a ‘sexy headline’ for the British tabloids (as an SAS officer told the Gibraltar inquest)? And who could foresee that the Sun, then a faltering broadsheet of mildly Labourite views, would become the tabloid-in-chief and cheerleader of a born-again chauvinism for twelve million readers? Its front-page headlines are inimitable. Of the IRA in general: ‘string ’em up!’ Of the three who were shot in Gibraltar: ‘why the dogs had to die.’ Then again, who in 1967 worried about the fate of Northern Ireland other than the Northern Irish, or about the gerrymandering and discrimination against its minority which kept the province intact? Or who could imagine an ensuing twenty years of terror and counter-terror which, at its last great manifestation on the British mainland, nearly killed a British prime minister and many of her cabinet?

I don’t want to go back further. Let’s avoid Oliver Cromwell and the potato blight. But is there anything which the head – rather than the gut – can latch on to in this pernicious cycle of cause and effect, some handhold on fairness and reason? One such handhold should be the rule of law, which has always found great favour with the British establishment who speak of it like a sacrament, inviolable, invulnerable to prejudice or political influence: the rule that sets the state morally above those who oppose it by violence. It would follow that the rule of law would be served by truth and that truth – the truthful reconstruction of events – would be the objective of any disinterested and open process of inquiry.

It was the duty of the Gibraltar inquest to use such a process to discover the truth of what happened and thus to see whether that discovery conflicted with the principles of the rule of law – in other words, to establish whether what was true was also legal, whether it was the symbolic British policeman or the symbolic British bandit who shot three unarmed people to death on the streets of Gibraltar on 6 March 1988. It was not a trial, it was an inquest, and was in many people’s view a sadly inadequate forum to determine what happened, but the British government insisted that it would be the only one. Six months after the killings, on Tuesday, 6 September, the coroner called his first witness into court. For the next four weeks he heard evidence and argument in a courtroom which, oddly enough, also heard the inquiry into the fate of the crew of the Marie Celeste after that abandoned barque was towed to port in Gibraltar in 1872. Sometimes during those four weeks it seemed we were in the presence of a mystery of equal proportions. There was rarely a day when a saying of one of Mrs Thatcher’s own party men did not come to mind: in the words of Jonathan Aitken MP, when you try to reconcile effective counter-terrorism with the ancient rule of English law, the result is ‘a huge smokescreen of humbug’.

2

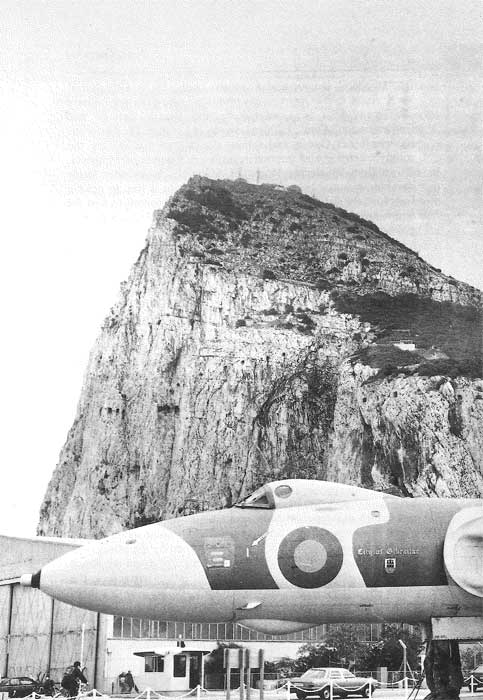

Gibraltar has only one overland entrance and exit. A large lump of Jurassic limestone, it points south into the Mediterranean from Spain. Sea surrounds it on three sides. Only to the north does water give way to land – a flat, low strip of plain about one mile long and half as wide joins Gibraltar to the sweep of the Costa del Sol. The airport runway crosses this strip from east to west, while further to the north are the fences and guard posts which mark the half-mile width of Gibraltar’s land frontier. The road into the colony bisects the fences and then the runway. Before visitors can reach the town by road, they must first pass through Spanish and British immigration control and then, if they are unlucky, wait at the traffic lights which control movement across the runway.

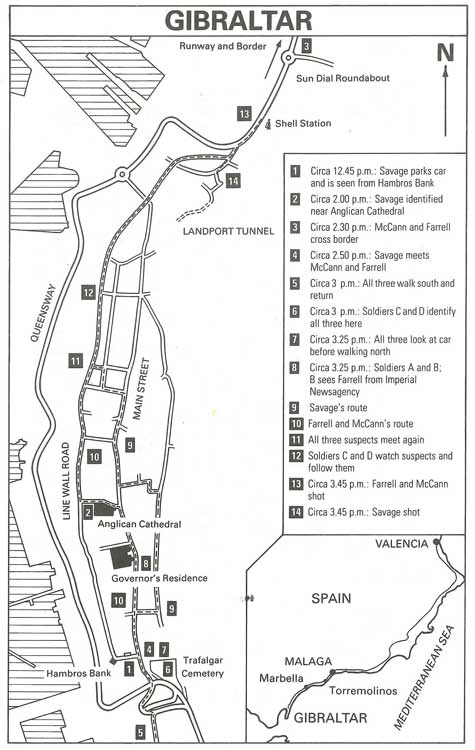

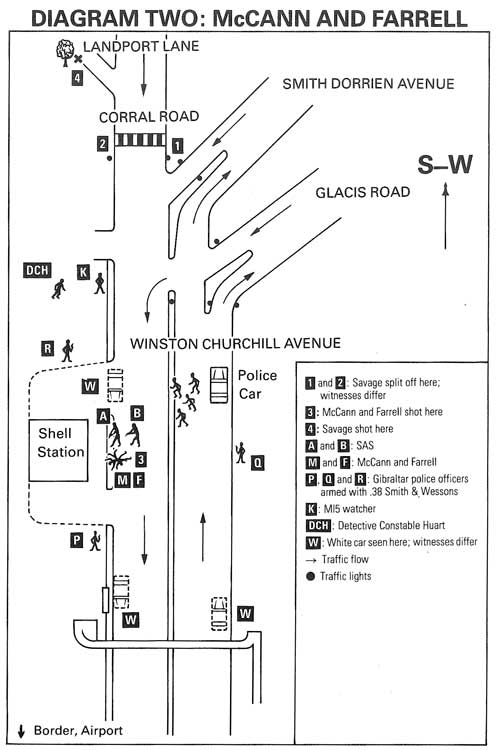

Sean Savage, Danny McCann and Mairead Farrell arrived by this route on Sunday, 6 March 1988. Savage came first. He drove a white Renault 5 across the border around 12.30 p.m. and parked it ten minutes later near Ince’s Hall at the south end of the town. At 2.30 p.m. McCann and Farrell crossed on foot. By 3.45 p.m. all of them were dead.

It seems likely (no, certain) that we shall never know their exact purpose on that day. None the less, certain aspects of it are beyond dispute. Within hours of their deaths, the Irish Republican Army in Belfast claimed all three as ‘volunteers on active service’, attached to a unit of the IRA’s General Headquarters staff. The next day the IRA admitted that the three had ‘access and control over’ 140 pounds of explosives. What the IRA would not divulge was the intended target, though on this particular point the British government’s scenario has never been seriously challenged. News bulletins on British radio and television on the evening of 6 March quoted briefings in London and Gibraltar which identified not only the target but also the place and time. According to several reports the three dead had intended to blow up the band of the Royal Anglian Regiment, which had recently served in Northern Ireland, as it assembled for the weekly changing of the guard ceremony outside the Gibraltar Governor’s residence two days later, on Tuesday, 8 March, at eleven in the morning.

As a description of intention, that may be entirely accurate. It was, however, a minor accuracy embedded in a larger untruth. Throughout Sunday evening and Monday morning the same reports also asserted that a bomb had been found in Gibraltar. The earliest reports were the most circumspect. At 6.25 p.m. on the television news, the BBC’s Madrid correspondent said that troops were searching Gibraltar’s main street, ‘following a report that a bomb had been planted near a public hall . . . but it’s not known if that report is genuine.’ Three hours later all circumspection was cast aside. At nine o’clock the BBC reported that 500 pounds of explosives had been packed inside a Renault 5 and, according to ‘official sources’, timed to kill British troops when they assembled for Tuesday’s parade. At 9.45 p.m. Independent Television News had further details. Three Irish terrorists had been killed in ‘a fierce gun battle’. Their bomb had been defused by ‘a controlled explosion’. It was becoming more evident, said ITN’s correspondent, ‘that the authorities came desperately close to disaster with a bomb being left in a crowded street and a shoot-out when innocent civilians were in the area.’

Monday’s newspapers all carried similarly certain accounts, though the size of the bomb varied from 400 to 1,000 pounds. On the BBC’s morning radio programme, Today, the Minister of State for the Armed Forces, Mr Ian Stewart, again spoke confidently of ‘the bomb’ and its timing for Tuesday’s parade. And yet this bomb was a fiction. There was not and never had been a bomb in Gibraltar, neither had the crowded streets of Gibraltar witnessed a gun battle.

At 3.30 p.m. on Monday afternoon, the Foreign Secretary, Sir Geoffrey Howe, rose to make a statement in the House of Commons. No bomb had been found; neither were the suspected terrorists armed. However, Howe added, ‘When challenged they [the dead] made movements which led the military personnel operating in support of the Gibraltar police to conclude that their own lives and the lives of others were under threat. In the light of this response, they were shot.’ What Howe then went on to say is worth examination, because its confusing mixture of hypothesis and reality echoed through the Gibraltar affair for the next six months and in fact formed the basis of the British government’s case at the inquest:

The suspect white Renault car was parked in the area in which the band of soldiers would have formed for the Tuesday parade. A school and an old people’s home were both close by. Had a bomb exploded in the area, not only the fifty soldiers involved in the parade, but a large number of civilians might well have been killed or injured. It is estimated that casualties could well have run into three figures. There is no doubt whatever that, as a result of yesterday’s events, a dreadful terrorist act has been prevented. The three people killed were actively involved in the planning and attempted execution of that act. I am sure the whole House will share with me the sense of relief and satisfaction that it has been averted.

The whole House did, for who would not want to prevent a carnage of innocents? When George Robertson, the Labour opposition spokesman, got to his feet, he seemed oblivious to the fact that the carnage would have been wrought by a bomb which in the course of Howe’s speech had quietly ceased to exist. Robertson congratulated the military on their ‘well-planned operation’:

The very fact that this enormous potential car bomb was placed opposite both an old folk’s home and a school underlines the cynical hypocrisy of the IRA . . . This House speaks with one voice in condemning unreservedly those in Ireland who seek to massacre and bomb their way to power. These people are evil. They kill and maim and give no heed to the innocents who get in their way. They must be dealt with, if any democratic answer is to be found.

Consider the statements of both men. Howe admits that there was no bomb; at the same time the shooting of three people prevented ‘a dreadful terrorist act’ because such an act had been planned in the minds of the dead who at some point in the future would have tried to implement it – had they been alive. This could be read as a confession to a lethal pre-emptive strike. Robertson, in reply, is understandably confused by the semantics of what has gone before. The car bomb seems to him still real and a cause for moral outrage; it is only ‘potential’ because it has not gone off.

Today it may be easy to separate the various elements in this extraordinary fudge, but at the time the government got away with it, aided by further semantic horseplay from the Ministry of Defence, a credulous media and an impolitic volubility from the IRA. We now know from the bomb disposal officer who gave evidence at the inquest that, if members of the British army in Gibraltar had ever imagined Savage’s car to contain a bomb, they knew by 7.30 p.m. on Sunday that it certainly did not. And yet throughout that night and the following morning the Ministry of Defence in London cultivated (or, at the very least, did not correct) the impression that a bomb had been found. At 4.45 p.m. on Sunday the Ministry of Defence confirmed that ‘a suspected bomb had been found in Gibraltar’. At 9 p.m. a statement was issued to the effect that ‘military personnel dealt with a suspect bomb.’ The following morning the Ministry was still repeating that ‘a suspected bomb had been dealt with.’

There is a strong temptation here, a temptation to use the word ‘lie’. Writer (and reader), resist it. According to the Ministry of Defence, the phrase ‘suspect bomb’ or ‘suspect car bomb’ is ‘a term of art’. As the army’s bomb disposal officer explained to the inquest it means no more than a car which, for whatever reason, is thought to contain a bomb. Hence you ‘find’ a suspect bomb by finding a car and suspecting it. Hence you ‘deal with’ a suspect bomb either by confirming its presence and defusing or exploding it, or by discovering that no bomb exists. Bomb disposal officers are brave men; nobody need mock the terms of their art. But unfortunately neither the British media nor Mr Ian Stewart, a defence minister, quite grasped the subtleties of their definitions. ‘Dealt with’ so easily became ‘defused’, while the size of the notional bomb grew in the minds of reporters in Gibraltar whose only source of information was the gossip of excited Gibraltar policemen. (That night, Ronald Sinden, assistant to the deputy governor, was appointed official press spokesman. He said memorably: ‘I am the only source of information, and I have no information.’)

These ‘facts’ had a formidable effect on the IRA, and the two statements it issued tried to correct what were rightly perceived to be untruths. The first did it no harm: ‘There could have been no gun battle because the three volunteers were unarmed.’ The second immeasurably helped the British government because, four hours before Howe’s statement, the IRA admitted that the three had ‘had access and control over’ 140 pounds of explosives. This was meant to correct reports of bombs six times that size with the consequent potential carnage, in the belief that the British government or media were simply exaggerating the size of a bomb that had actually been found. But of course, as Howe was to admit, no bomb had been found; the IRA, by misunderstanding the radical nature of the lie it was trying to correct, confessed to a bomb thirty hours before the Spanish police found it forty miles away on the Costa del Sol. From the IRA’s point of view, an opportunity to embarrass the British government for thirty hours had been wasted.

Little of this information was ever presented to the inquest as evidence – perhaps rightly; much of it is after and outside the facts. But here, only twenty-four hours after the killings, some lessons can be drawn and kept in mind. One, the British government and its servants are no fools. Two, there are already reasons to distrust the British version of events. And three, London, rather than its colonial outpost, Gibraltar, pulls the strings.

3

One day in Gibraltar I tried to buy a map. This was in early May, a couple of months after the killings. Maps are not hard to come by in Gibraltar, in fact the tourist office gives them away, and these are perfectly good if you want to find your way to the feeding grounds of Gibraltar’s famous apes, or the Holiday Inn, or any of the bits and pieces of old military science – steam-driven artillery, stout fortifications, labyrinthine tunnels – which are Gibraltar’s chief contribution to history. These maps specialize in the past. About the present they are more reticent. Naturally, I didn’t expect them to fill in the details of the naval base or the munitions dumps or the copse of radar and radio masts stuck high on the rock above the town; these are contemporary military secrets. But even with ordinary civilian geography they were vague, as though when it came to housing estates and dual carriageways the cartographer had unhooked his jacket from the back of the chair and taken the rest of the day off.

Farrell, Savage and McCann died in the middle of the civilian quarter. Without a good map it was difficult to follow the arguments about who saw them die, from where. I asked a woman in Gibraltar’s bookshop about ordnance survey maps: ‘They are not available to the public.’ Not knowing Gibraltar, I found this hard to believe. Whatever the vices of the British Empire, one of its virtues is the legacy of careful cartography (imperialism needed to be sure of what it owned) still found in the old British capitals of Asia and Africa and even, I am sure, among those forgotten islands – Pitcairn, St Helena and others – which together with Gibraltar, Hong Kong and the Falklands form the rump of the colonial empire.

Eventually somebody suggested the Public Works Department. There I met the chief draughtsman who asked me to choose from a fine selection of maps of different scales. I picked one, and he went off to have it photocopied. Another man approached.

Would this have anything to do with the shootings?

Only indirectly, I said. It was simply a journalistic exercise to show the exact location, and in the interests of accuracy it would be good to work from the best available map.

The man nodded and went away. I heard him making several telephone calls, successively marked by a rising tone of deference. He returned. ‘I am sorry but the Attorney-General has refused me permission to sell you a map.’

The Attorney-General himself! This struck me then as the kind of absurd infringement of liberty that might happen in Evelyn Waugh’s Africa. But the better I got to know Gibraltar the more typical it seemed. Gibraltarians do not suffer from an over-developed sense of freedom, and this is not just because they are colonials. Their whole identity is antithetical: to be Gibraltarian is not to be Spanish; to be free is not to be Spanish. Therefore to be free and Gibraltarian is to be British, because Britain is all that stands between them and a successful Spanish reclamation of their rock. Spain is only a mile from the centre of the town, and yet bread is imported from Bristol (it comes frozen, in lorries) and newspapers from London. No Spanish newspapers can be found; nobody in Gibraltar reads El País; the local radio and television stations broadcast only in English. And yet Spanish is the first language of the Gibraltarian, who speaks it at home and in the street (and badly only to Spaniards). To judge by their names, many if not most Gibraltarians are as Spanish as any man or woman from Cádiz or Seville. And yet they mock Spain. Echoing the tabloid xenophobia of the mother country (‘dago’ and ‘wop’), they call Spaniards ‘slops’ and ‘sloppies’. Every weekend they drive out to the resorts of the Costa del Sol and then come home to complain. ‘Too many slops on the beach today, Conchita.’ ‘Let’s stay on the Rock next weekend, Luís.’ Nor do they believe that Spain has changed. To them it will always be Franco’s Spain, rich only in cruel policemen and opaque bureaucrats. But surely, I asked a shopkeeper one day, Spain was now prospering, freer, much more democratic? ‘Maybe so, but Spaniards don’t understand the word freedom like we do. To them it means the freedom to take drugs and screw around, to behave badly, which they couldn’t do under Franco. It’s not British freedom or democracy like you and I know it.’

Freedom! Democracy! Executive authority in Gibraltar is vested in the Governor, by tradition a retired British military man, who is appointed by the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office 1,200 miles away in London. The Governor represents the Queen and retains direct responsibility for the colony’s defence and internal security. A Council of Ministers, drawn from an elected House of Assembly, looks after lesser domestic matters, but even here the Governor is free to poke a finger in: the list of ministers must first be submitted to him for approval, and he can intervene later if he thinks that any of their policies are a threat to the colony’s stability.

Few Gibraltarians object to this semi-autocracy. Could a government in distant Madrid deliver more liberty? And in any case to object is to be pro-Spanish, and the colony owes everything, its origins and continued existence, to Britain. Its limited local democracy is a recent invention: not until after World War Two did the civilian population have any say in its colony’s affairs. For 200 years its citizens had been there only to serve the British army and navy, who, together with the Dutch, had seized the fort from Spain in 1704. Nine years later the Treaty of Utrecht ceded it in perpetuity to the conqueror. The local Spanish were expelled and new camp-followers drawn from Malta and Genoa and the Jewry of Morocco. By the nineteenth century, recurrent sieges and the Rock’s bold outline, prickling with guns, had found Gibraltar a firm place in the imperial imagination: ‘as safe as the Rock of Gibraltar’.

This historic symbolism is still powerful; ‘Free since 1713’ says the graffiti on Gibraltar’s walls, in the same pugnacious red, white and blue as the slogans (‘Remember 1690’) of Protestant Belfast. But even more potent are the contemporary facts. Today Gibraltar has a civilian population of about 29,000 – 20,000 Gibraltarians, the rest British or immigrant Moroccan labour – all of whom squeeze into 2.25 square miles of territory, much of it uninhabitably steep (the Rock rises to 1,400 feet), half of it owned by the Ministry of Defence. The Royal Air Force controls the airport and the Royal Navy the harbour, while the army spreads out in barracks to the south. Regiments come here after tours of duty in Northern Ireland, in part for rest and relaxation but also to keep in shape for further tours: according to reports, one of the Rock’s large caverns contains a mock Ulster village made of wood – a main street, four side-streets, two shops, a Roman Catholic church called St Malachy’s, a school and a women’s lavatory. What goes on here under artificial light? Raids, sieges and patrols, one assumes, stun bombs thrown into the ladies’ loo, the school stormed, sanctuary denied at St Malachy’s.

At night the troops come out to play. The usual sights and sounds of a garrison town: rounds of English lager in the Gibraltar Arms, the Olde Rock and the Angry Friar, chips at Mac’s fish bar, maybe a disco down at the RAF base. By eleven the military police are cruising down Main Street. By two in the morning only the brain-dead are left, bumping into shop windows, moaning, crying. ‘Oo you fackin’ callin’ a cunt, Kevin? You fackin’ cunt you.’ Gibraltarians do not complain; these lads are their bread and butter, less an ancestral burden than an heirloom. When the novelist Thackeray visited Gibraltar in 1844 what struck him mainly was the sight of befuddled seamen. But the British Mediterranean fleet was long ago disbanded, and these days respectable young Gibraltarian women no longer weight their handbags with stones. Life in a sense has improved.

This then is the town in which Farrell, Savage and McCann spent the last hour or two of their lives. Had they lived and returned and managed to detonate their bomb, then the result would be what British Intelligence knows as ‘a spectacular’, worth ten times the publicity of ten bombs in Belfast or County Armagh. As it was, they died among memorials to the enemy’s history – Farrell and McCann on the pavement of Winston Churchill Avenue, Savage just below King’s Lines – having first been watched from the tombstones of Trafalgar Cemetery, the forecourt of the Anglican Cathedral and a small shop called the Imperial Newsagency where Gibraltar queues up for its air-freighted copies of the Sun.

4

Of course they had been watched for months.

According to statements made by the Spanish government soon after the killings, McCann and Savage were first spotted at Madrid airport arriving on a flight from Malaga on the Costa del Sol in November 1987. They were travelling under the aliases Reilly and Coyne. Around this time the Spanish police also detected a third IRA member in Malaga, a woman – not Mairead Farrell – who used the alias Mary Parkin. She, along with Savage and McCann, returned to the Costa del Sol again in February.

In the meantime the Gibraltar authorities had abruptly cancelled the changing of the guard ceremony scheduled for Tuesday, 8 December – the guardhouse, they decided, needed repainting – and did not resume it until 23 February. It was also on that day, according to British intelligence, that ‘Mary Parkin’ once again visited Gibraltar, to attend the ceremony; she returned the following Tuesday, 1 March. She then disappeared.

Four days later, on Friday, 4 March, McCann and Savage reappeared for the third time on the Costa del Sol and were joined there by a second woman, soon identified as Mairead Farrell. All three came from Belfast, and exhibits produced during the inquest (a boarding pass, an air ticket and an airline timetable) suggest that Farrell took three flights to reach Malaga: from Dublin to Brussels by Aer Lingus, from Brussels to Madrid by Sabena, and then on to Malaga by an internal Spanish flight. McCann and Savage may well have come the same way; the man who drove McCann to Dublin airport was stopped on his way home to Belfast by British troops at the border on Thursday evening, 3 March. It seems unlikely that they would risk travelling on the same series of flights on the same day – very imprudent terrorist behaviour – but with the question of the exact sequence of their arrival in Malaga the story reaches another large contradiction.

Of course they had been watched. Or had they?

In the weeks after the killings, there seemed to be no doubt. On 9 March the Spanish Interior Ministry issued a communiqué which said that the Spanish police had ‘maintained surveillance on the suspects’ until they left Spain and entered Gibraltar. On 21 March Señor Augustín Valladolid, then the senior spokesman for the Spanish security services, went further. In a briefing to Harry Debelius, an American correspondent based in Madrid, Valladolid said that Spain had accepted a commitment in November to follow the IRA unit and to keep the British informed of its movements. On 6 March, therefore, Savage, driving a white Renault, was followed all the way down the coast road to Gibraltar. To quote the affidavit later sworn by Debelius, Valladolid said that:

The method of surveillance used was as follows: (a) four or five police cars ‘leap-frogged’ each other on the road while trailing the terrorists so as not to arouse suspicion; (b) a helicopter spotted the car during part of the route; (c) the police agents were in constant contact with their headquarters by radio; (d) there was observation by agents at fixed observation points along the road.

Debelius’s affidavit also states that Valladolid told him that the Spanish police sent ‘minute-by-minute details’ of the Renault’s movements directly to the British in Gibraltar. Later, in a telephone conversation, Valladolid told him that two members of the British security services had also worked with the Spanish surveillance teams in Malaga.

These statements from members of the Spanish government – and many others – are public knowledge.

But: of course they had not been watched.

By the time of the inquest, the matter was no longer certain. There were, of course, no Spanish witnesses – not in a Gibraltar court. And every other witness – members of the Gibraltar police, the British military and British intelligence – flatly denied that the three had been watched. Impossible. Their information, they insisted, was limited to a reported sighting of the three in Malaga.

Of course: otherwise how could the bomb – or the car believed to have contained the bomb – have reached the centre of Gibraltar unchecked?

The likely facts are these: the Spanish police followed McCann and Savage, who were both known to them, but either missed or lost Farrell, whom they had never seen before. All three had aliases and false documentation. Farrell flew out of Dublin as Mary Johnson, but entered Gibraltar as Mrs Katherine Alison Smith, née Harper. For two days the Spanish police could not trace her, though by midday on 5 March they at least knew who to look for. Savage and McCann, on the other hand, presented no difficulty. As Señor Valladolid told Tim McGirk of the Independent in May: ‘We had complete proof that the two Irishmen were going to plant a bomb. We heard them say so.’ Under the names Coyne and Reilly, McCann and Savage checked into the Hotel Escandinavia in Torremolinos, a few miles down the coast from Malaga, towards midnight on 4 March, and stayed two nights. Farrell did not register, although some women’s clothes were found later in the room: she may have stayed with them, or she may have left her luggage there while she drove through Friday and/or Saturday night to collect and deliver the explosives.

Three cars were hired. A man thought to be Savage, using the name John Oakes, hired a red Ford Fiesta about midday on Friday, 4 March, from a firm in Torremolinos. Spanish police found the car on Sunday evening, a few hours after the shootings, parked in a car park several hundred yards from the Gibraltar border. Its contents included false documents, a money belt containing £2,000, a holdall covered in dust and soil which looked as though it might have been buried, several pairs of gloves, a dirty raincoat and anorak, tape, wire, screwdrivers and a small alarm clock. The office manager of the car hire firm retrieved the car and said it had been driven 1,594 kilometres and was covered in mud. A policeman told him that it had been to Valencia and back.

Using the alias of Brendan Coyne, Savage then hired another car, a white Renault 5, from Avis in Torremolinos about eleven on Saturday morning, 5 March. The next day he drove it into Gibraltar and parked it at Ince’s Hall, where the band of the Royal Anglian Regiment would leave their bus, form up and fall out again on Tuesday (during the inquest this became known as ‘the de-bussing area’). This car became the suspect car bomb. Some time after the three were shot, an army bomb disposal team blew open its bonnet, boot and doors. It contained car hire literature.

Farrell also hired a car, the third car, using a British driving licence in the name Katherine Alison Smith, from a firm called Marbessol in Marbella, the next large resort down the coast from Torremolinos. Marbessol’s manager recalled that she came into the office about 6.30 p.m. on Saturday evening, 5 March, to make a provisional booking, and returned about 10.30 a.m. the next morning to collect a white Ford Fiesta. The manager later told a reporter from Thames Televison, Julian Manyon, that she looked exhausted, ‘as though she hadn’t been to bed’. Spanish police found the car two days after the killings, on Tuesday evening, 8 March, in an underground car park just off Marbella’s main street and about a hundred yards from the Marbessol office. It had been driven less than ten kilometres. It contained 141 pounds of Semtex, a plastic explosive made in Czechoslovakia, wrapped in twenty-five equal blocks; ten kilos of Kalashnikov ammunition; four electrical detonators made by the Canadian CXA company; several Eveready batteries; and two electronic timing units with circuit boards which, according to the evidence of a Ministry of Defence witness at the inquest, bore the same patterns or ‘artwork’ as previous IRA bombs. The timers had been set for an elapsed time of ten hours forty-five minutes and eleven hours fifteen minutes: a fail-safe device. If set running at, say, midnight on Monday the first would have detonated the bomb at 10.45 a.m. on Tuesday morning. If it failed, the second timer would give the bomb a second chance half an hour later; which represents the difference in time between the Royal Anglian band leaving the bus and preparing to board again.

Events during those few days in Spain, therefore, may well have unfolded like this: Savage hires the red Fiesta and at some point hands it over to Farrell, whom the Spanish police have the least chance of detecting. Savage then meets McCann and the two idle in Torremolinos while Farrell drives 700 kilometres north to Valencia, collects the explosives and returns. She may have made this journey on Friday night and Saturday, or just possibly (driving hard) on Saturday night and Sunday morning between her two appearances at the car hire office in Marbella. Then, either on Saturday around 6 p.m. or Sunday around 10 a.m., she parks the red Fiesta and its bomb in the underground car park. At 10.30 a.m. on Sunday she picks up the white Fiesta, takes it for a run round Marbella’s one-way traffic system, then parks it underground next to the red Fiesta. She and one of the men transfer the explosives while the third keeps watch. Savage, whom British intelligence insists was ‘the expert bomb-maker’, checks that the bomb has been safely transferred and then, at about 11.30 a.m., sets out for Gibraltar in his white Renault 5. Farrell and McCann follow a couple of hours later in the red Fiesta, park it and cross the border on foot. By this hypothesis, Savage is using the white Renault as – in another of the bomb disposal squad’s terms of art – ‘a blocking-car’, a car which would hold the parking space in Gibraltar until the white Fiesta with the bomb was driven into the same position on Monday night.

Given the traffic in Gibraltar, such a precaution makes sense. To make a small diversion into social history: one consequence of the colony’s acute land shortage is that most people live in small apartments; one consequence of its military history is that most apartments are owned by the government. Only 6 per cent of Gibraltar’s homes are owner-occupied. Money can’t chase property so it chases cars instead. At the most recent count 8,000 households owned 15,000 cars, or 555 cars for every mile of narrow Gibraltarian road. Parking is a problem which ‘Mary Parkin’ could not fail to have noticed on her reconnaissance trips.

Very little of this information was mentioned at the inquest.

5

The second time I flew to Gibraltar I noticed a man in Club Class reading Doris Lessing’s novel, The Good Terrorist. He took it up soon after we lifted from Gatwick and didn’t put it down again until we were over the Mediterranean for the Gibraltar approach. This was unusual behaviour. Club seats on Gibraltar flights are taken up mainly by off-shore investors and English expatriates who have ‘companies’ registered in the colony or real estate on the Costa del Sol. Fugitives from British weather and British tax laws, they tend not to be great readers–books not being duty-free.

The man turned out to be a diplomat with the British Foreign Office. A few months later he returned for the inquest. For four weeks he sat in court with a colleague from the Ministry of Defence and at the end of each day both made themselves available to brief the press; sometimes as the equivalent of ‘spin-doctors’, there to put the best British gloss on the day’s proceedings, and sometimes (helpfully) as translators of military or legal jargon. I can’t imagine that Lessing’s fictional insights into terrorist behaviour played much of a part here. Her characters are muddled, alienated members of the English middle-class whose violent rage against the state springs from domestic roots, smug parents and unhappy childhoods. They are inept at what they do. Nobody in court suggested that Savage, Farrell and McCann were inept. British military and intelligence witnesses spoke of them as ‘ruthless’, ‘fanatical’, ‘dedicated’, ‘experienced’ and ‘professional’. And yet outside the court, in Gibraltar and London, the government’s off-the-record conversations stressed their surprising amateurishness. The British had expected professionalism and planned accordingly (so this private argument ran), only to find themselves up against three people who behaved like novices. Had they behaved like professionals–that is, as the British said they expected them to– then their deaths would not have been controversial. Their amateurism had let the British down.

Who were Savage, McCann and Farrell, and how good were they as professional terrorists?

Sean Savage, the unit’s technician, was twenty-three and the youngest and least known. He grew up in Catholic West Belfast. When he was four, the houses on the streets around his birthplace were burned down by Protestant mobs. At the age of seventeen, he joined the IRA; according to his obituary in Ireland’s Republican News, he was ‘a quiet and single-minded individual who neither drank nor smoked and rarely socialized,’ and who had ‘an extremely high sense of personal security.’ Savage seems never to have worked, at least outside his business for the IRA, but unusually for West Belfast both his parents have jobs. His family insist that they knew nothing of his involvement with the IRA, though he was arrested (and then released without charge) in 1982. The parents are by all accounts respectable, religious people. His sister Mary engraves crystal in a Belfast factory. According to her, Savage was an enthusiastic cyclist, amateur cook, Gaelic speaker and night-school student of French. He did well at school. His brother has Down’s Syndrome and Savage often took care of him. His obituary records: ‘His dedication to the struggle was total and unswerving. To his fellow volunteers he was a strong, steadfast comrade, whose sharp and incisive judgement was relied on in tricky situations.’

Daniel McCann, the unit’s leader, was thirty and well known to all sides in the Irish conflict. The Republican News spoke of him as ‘the epitome of Irish republicanism’. He was first arrested as a sixteen-year-old schoolboy and sentenced to six months imprisonment for rioting. He joined the IRA soon after. Between 1979 and 1982 he spent three terms in prison on charges which included possession of a detonator and weapon. Later in 1982 he was arrested and held with Savage and two others after information was passed to the Royal Ulster Constabulary from a man already in their custody. But the charge was dropped and the four released. His family have run a butcher’s shop in the Falls Road, West Belfast’s main street, since 1905. At the inquest an SAS officer called him ‘the ruthless Mr McCann’. His obituary records: ‘He knew no compromise and was to die as he had lived, in implacable opposition to Britain’s criminal presence in our land.’

Mairead Farrell had become an important public figure in the armed republican movement by the time of her death, aged thirty-one–and perhaps its most important woman. She joined the IRA aged eighteen and went to jail a year later, in 1976, for planting a bomb at the Conway Hotel, Belfast. Of her two male companions on that bombing, one was shot dead by the RUC on the spot and the other died on a prison hunger-strike in 1981. Farrell served ten years in Armagh jail and Maghaberry women’s prison and herself became prominent as a hunger-striker, the ‘Officer Commanding’ other IRA women prisoners and leader of the ‘Dirty Protest’, smearing excrement on the walls of her cell. After her release in 1986 she spoke at political meetings throughout Ireland and enrolled as a politics undergraduate at Queen’s University, Belfast. She defined herself as a socialist; many also saw her as a feminist. Her family are shopkeepers, prosperous by the standards of West Belfast (they own their own house). Neither her parents nor her five brothers have any affiliations with the IRA. Her four brothers are businessmen; a fifth, Niall, is a freelance journalist and activist for the Irish Communist Party, which sets itself apart from the IRA’s ‘armed struggle’. In a sense Farrell wrote her own obituary in one of her last interviews: ‘You have to be realistic. You realize that ultimately you’re either going to be dead or end up in jail. It’s either one or the other. You’re not going to run forever.’

Mary Savage, Niall Farrell and Seamus Finucan, Mairead Farrell’s boyfriend, attended the inquest, and sometimes I’d cross the border to their cheap hotel in Spain and meet them for a meal or a drink. They struck me as intelligent and, I think, honest people; it was often easy to share their indignation at what Niall Farrell described as a ‘set-up’ or a ‘fix’. But our conversation had its limits; discussion of the state’s morality could not easily be widened to include the moral behaviour of the deceased. Good terrorists? A case might be made for Farrell. Her only known bombing was preceded by a warning; there were no casualties. As for Savage and McCann, we don’t know what part their ‘dedication’ and ‘implacable opposition’ played in the ending or maiming of life.

But good terrorists in the professional sense? As Farrell had spent most of her adult life in prison and had been free for only eighteen months, it is difficult to see how she could have perfected her trade. Certainly she was careless or superstitious enough to wear a prison medallion – ‘Good luck from your comrades in Maghaberry’ – around her neck when she entered Gibraltar. McCann? His friends describe him as ‘charismatic’ and ‘a natural leader’. But professional? When he was shot, he was clutching a copy of Flann O’Brien’s novel, The Hard Life. Farrell’s bag contained sixteen photocopied pages of a work entitled Big Business and the Rise of Hitler by Henry Ashley Turner Junior.

Both had some of the highest profiles within the IRA. To send either of them on a foreign mission which required safe passage through five different border checks and airport controls sounds like ineptitude. To send both smacks of desperation. Soon after their deaths recriminations began to be heard inside the IRA to this effect. But that was in private.

6

The three bodies stayed in Gibraltar for more than a week. First came the autopsy, then the identification by another Farrell brother, Terence, and a representative from Sinn Féin. The embalming posed a problem. Lionel Codali, the undertaker, said that with few staff members at his disposal the process of restoration and preservation would take at least two days. (In Savage’s case, though Codali did not say this, there was a great deal to restore.) Eventually they were ready to be air-freighted. But by whom?

Scheduled flights from Gibraltar go only to London; rumours suggested that baggage handlers at both ends, Gibraltar and Gatwick, might refuse to touch the coffins. Irish charter companies excused themselves on grounds of lack of aircraft. At length an English company took the contract. The bodies were loaded by British servicemen from the Royal Air Force and reached Dublin on Tuesday, 15 March.

They were driven north the same evening. Sympathetic republican crowds turned out to see the cortège as it passed through the counties of Dublin, Meath and Louth, but later, over the border, it was stoned by knots of Protestants from the edge of the motorway. That night at a requiem mass for Farrell in Belfast, Father Raymond Murray said that she had died ‘a violent death like Jesus . . . she was barbarously assassinated by a gunman as she walked in public on a sunny Sunday afternoon.’ On Wednesday, 16 March, several thousand spectators and mourners turned out for the funeral at Milltown Cemetery, Belfast, where the three were to be buried in the corner of the ground reserved for republican martyrs. About 1.15 p.m., as the first coffin was about to be lowered into its grave, a man began to lob grenades and fire a pistol into the crowd. Mourners chased him from the cemetery and on to the motorway nearby. Often he turned to fire at his pursuers, crying: ‘Come on, you Fenian fuckers’, and ‘Have some of this, you IRA bastards’. A mourner told The Times: ‘He seemed to be enjoying it. He was taking careful aim and firing at us, just as if he was shooting clay pigeons.’ After the crowd caught up with him, he was beaten unconscious and would have been beaten to death had not the police intervened to carry him away. Three men died during the grenade attack; another two people were critically wounded; sixty-six were hurt.

On Saturday, 19 March, another large crowd assembled at Milltown Cemetery to witness the funeral of Kevin Brady, an IRA activist and one of the three killed in the cemetery three days earlier. As the cortège made its way up the Falls Road a Volkswagen Passat drove towards it, stopped, reversed and then got hemmed in by taxis accompanying the funeral. The car contained two British soldiers in civilian clothes, Corporals Derek Wood and David Howes of the Royal Corps of Signals, who were dragged from the car, beaten, stripped and shot dead, amid shouts of ‘We have got two Brits’. Spokesmen for the British army said they could think of no reason why Wood and Howes had driven to the funeral, other than misplaced curiosity. Mrs Thatcher described their deaths as, ‘an act of appalling savagery . . . there seems to be no depths to which these people will not sink.’

A lethal chain of events which began in Gibraltar on 6 March had ended thirteen days later in Belfast with a total of eight dead and sixty-eight hurt. The last two deaths, however, imprinted themselves on the British imagination in a way the first six never could. They were young British soldiers killed in view of press and television cameras; the most enduring image from that time shows one of their naked carcasses full-length on the ground like something from an abattoir, with a kneeling priest administering the last rites.

It was not a time that encouraged the asking of difficult questions about the killings in Gibraltar. None the less, by the end of the month, Amnesty International announced that it intended to investigate the shootings to establish whether they were ‘extrajudicial executions’. The government was contemptuous. Mrs Thatcher told the House of Commons: ‘I hope Amnesty has some concern for the more than 2,000 people murdered by the IRA since 1969.’ One of her former ministers, Ian Gow, described the investigation as ‘a stunt . . . undertaken apparently on the behalf of three terrorists mercifully now dead.’ But real government fury had yet to show itself.

The British press had stayed obediently, perhaps slothfully, silent on Gibraltar – this was not one of its more glorious moments. Then in late April Thames Television announced that its current affairs team had made a thirty-minute documentary on the shootings which included eyewitness accounts of how the three had died. The government moved quickly to have it stopped. Sir Geoffrey Howe telephoned the chairman of the Independent Broadcasting Authority to ask him to postpone the programme’s transmission until after the inquest. It was the job of the law rather than ‘investigative journalism’ to throw light on the Gibraltar affair: journalism would simply muddle or prejudice the legal process. We should await a legal verdict, even though Sir Geoffrey Howe himself had not obeyed that stricture when on 7 March he issued his version of events, which had, by its amplification in the press, become the conventional British wisdom.

When the Independent Broadcasting Association resisted Sir Geoffrey, Tom King, the Northern Ireland Secretary, told Parliament that the programme amounted to ‘trial by television’. Mrs Thatcher took up the phrase. ‘Trial by television or guilt by accusation is the day that freedom dies,’ she told a group of Japanese journalists on the day before the broadcast. When asked if she was furious, as she often is, she replied that her reaction went ‘deeper than that’.

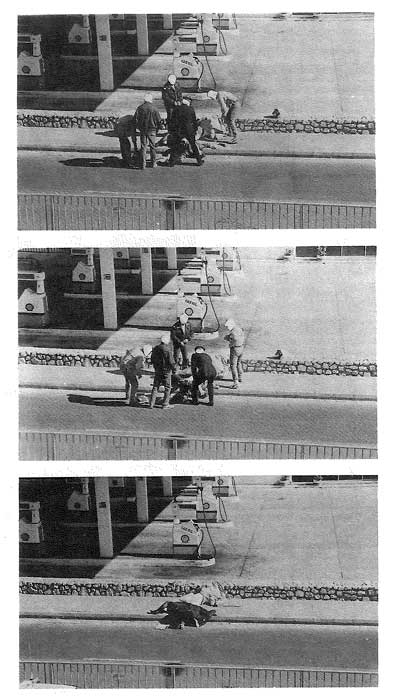

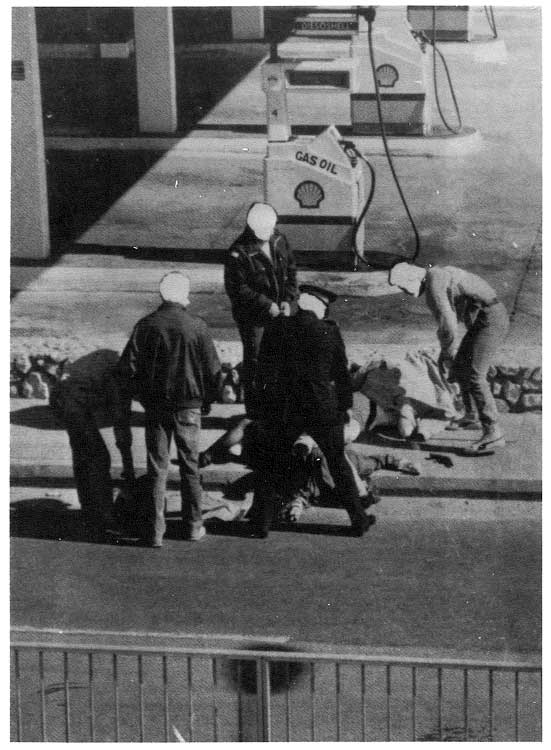

The programme, ‘Death on the Rock’, went out on the evening of 28 April. The response was immediate: an immense uproar, which increased when the BBC, also refusing to bow to government pressure, broadcast a similar investigation a week later in Northern Ireland. Both programmes implied that the government’s version of events, as stated by Sir Geoffrey Howe to Parliament on 7 March, was not necessarily complete. Thames Television had found witnesses who said that they had heard no warning before the shots were fired, that McCann and Farrell had their hands up in surrender when they were killed, and that two and possibly all three of them seemed to have been shot again after they fell to the ground. The programme had discovered these witnesses by knocking on the doors of the apartments surrounding the Shell petrol station on Winston Churchill Avenue, the scene of the killings. It is a traditional journalistic method of investigation. It is also a traditional police method, but not one, at that stage, that had been adopted by the Gibraltar constabulary. Several dozen apartments had a good view of the spot where Farrell and McCann died. The programme’s researcher, Alison Cahn, found that most of their occupants were reluctant to discuss what, if anything, they had seen on 6 March. Two did, however.

Mrs Josie Celecia said that she was looking from the window of her flat, which faces the petrol station from the other side of Winston Churchill Avenue, when she heard two shots. She turned to look in their direction and then heard four or five more shots as a casually dressed man stood over two bodies.

Mrs Carmen Proetta, whose flat lies 100 yards to the south of the Shell station on the same side of the road, gave a more complete, and even more controversial, picture. She had been at her kitchen window when a siren sounded and several men with guns jumped over the barrier in the middle of Winston Churchill Avenue, and rushed towards a couple who were walking on the pavement near the petrol station. They put their hands up when they saw these men with the guns in their hands. There was no interchange of words, there were just shots. And once they [the couple] dropped down, one of the men, this man who still had the gun in his hand, carried on shooting. He bent down and carried on shooting at their heads.’

A third witness, Stephen Bullock, described what he had seen about 150 yards to the south. Bullock, a lawyer, had been walking with his wife and small child when he heard a siren and shots almost simultaneously. He looked in the direction of the sounds, towards the petrol station, and saw a man falling backwards with his hands at shoulder height. ‘He was still being shot as he went down.’ The gunman was about four feet away. ‘I think with one step he could have actually touched the person he was shooting.’

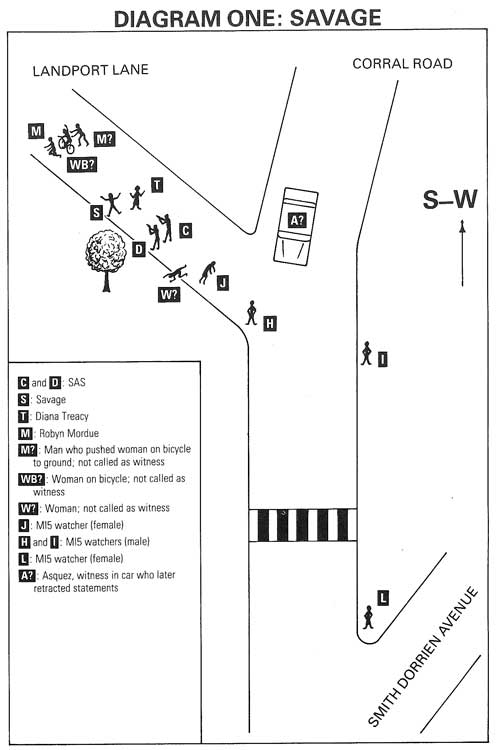

Other evidence from two anonymous witnesses said that Savage had also been shot on the ground, while a retired bomb and ballistics expert with a distinguished army record in Northern Ireland appeared on the programme casting doubt on the possibility that anyone could have believed that Savage’s white Renault 5 contained a bomb. According to this expert, George Stiles, it would be obvious to any experienced observer that the Renault was not low enough on its springs – the wheels were not against the wheel-casings – and that therefore the car ‘clearly carried no significant weight of explosives’.

The response of the press was curious. Little of its coverage addressed the programme’s new evidence. Instead a campaign was begun to discredit the witnesses and the journalists at Thames Television. Two of the government’s strongest media supporters – Rupert Murdoch’s Sun and Sunday Times – led the campaign, and the viciousness of their attacks surprised even some of the newspapers’ employees. Mrs Carmen Proetta in particular took a mauling. She emerged on the front page of the Sun as an anti-British whore (‘the tart of gib’), an allegation which had its perilous foundation in the fact that her name had briefly appeared on company documents as a director of a Spanish tourist and escort agency.

The programme emerged as such a powerful challenge to the government and its version of events that the government has not, apparently, forgiven Thames Television. But at the time, the government’s complaints wore a nobler face: journalism had no place in the legal process, and that process, as it had said many times before, was entirely a matter for the Gibraltar coroner and magistrate, Mr Felix Pizzarello.

But what had happened to that process? There was still no date fixed for the inquest. Two months went by before the coroner’s office finally announced that the inquest would begin on 27 June. For a fortnight or so, this date held good. Then at 11 a.m. on Monday, 27 May, a press spokesman for the prime minister’s office announced that the inquest would be indefinitely postponed. The government, said the spokesman, had received this news from Mr Pizzarello over the weekend, adding that the postponement was of course entirely Mr Pizzarello’s decision. The government could not interfere with Mr Pizzarello’s timetable.

The spokesman, however, was unaware that Pizzarello himself did not know of the decision he had taken. The same morning that the government announced the decision made by Pizzarello over the weekend, Pizzarello was telling Dominic Searle, a reporter on the Gibraltar Chronicle and correspondent for the Press Association, that he was considering a postponement – but only considering it. When Searle heard the news from London he went back to the coroner’s office, to be told that Pizzarello was still only considering a postponement. Eventually, at 4 p.m., the coroner vindicated Downing Street’s prescience and announced an indefinite postponement.

There is a temptation here, a temptation to use the word ‘horseshit’. Reader, resist it. Pizzarello had good reason to delay proceedings, and the pressure came from below rather than above. Ten days before, a young Gibraltar woman, Miss Suyenne Perez, had written to the coroner in her capacity as chairwoman of the Gibraltar International Festival of Music and the Performing Arts to remind him that this year’s festival was scheduled to begin on 24 June. Four days of it would coincide with the inquest. Perhaps, Miss Perez wrote to the coroner, he would like to consider changing his dates to avoid an undue strain on police resources?

In the event, the festival consisted of one beautiful baby contest, and, in the evening, a number of recitals held in the school halls. Neither the British government nor Pizzarello nor the Gibraltar police ever advanced any other reason for the inquest’s postponement. And so the inquest was once again delayed, this time for a further two months, by which time Parliament had gone, on holiday – there would be no troublesome questions – and Mrs Thatcher could prepare for a visit to Spain.

7

During late summer a peculiarly local climate overcomes Gibraltar. For several weeks life conducts itself under a thick cloud, while only a mile away Spain sparkles in the sun. Gibraltarians make jokes about this cloud – even our weather is English! They know it as ‘the Levanter’ and its causes are interesting enough. The prevailing wind in Gibraltar is easterly. From June to September it blows across a thousand miles of warm Mediterranean, gathering moisture on the way, until it strikes the rock’s sheer eastern face and soars up 1,400 feet. The air cools rapidly, its moisture becomes vapour, and a dense white cloud tumbles over the rock’s escarpment to blot out the sun from the town, which lies in a windless pocket to the west. The effect is spectacular – look up from Main Street towards the ridge and you can imagine a blazing, smoking forest on the other side – but also oppressive. As the colony’s historian, John D. Stewart, writes:

It obscures the sun, raises the humidity to an uncomfortable degree, dims and dampens the town and the ardour and enterprise of everyone in it. It is, inevitably, hot weather – too hot – when this added plague arrives, and now it is hot and humid and without even the benefit of brightness.

It was September, the Levanter season, and we had gathered at last for the inquest. Everybody sweated. The courtroom had a high ceiling from which fans had once been suspended; an effective system of Victorian ventilation helped by the windows high in the walls. But as part of some colonial modernization the fans had been removed, the windows double-glazed and air conditioning installed. The air conditioning had broken down. Sometimes the coroner ordered the doors to be opened; papers would then blow around; the doors would be closed again. Upstairs in the press gallery shirts grew dark from sweat stains.

The court was wood-panelled in the English fashion, brown varnish being sober and traditional, and from the gallery its layout looked like this. Straight ahead and raised above the courtroom floor sat the coroner. A large plaster representation of the royal coat of arms was stuck to the wall above him; the lion and the unicorn, splendidly done up in red, white and blue, picked out in gold, and complete with its legends in courtly French which say that the English monarchs have God and right on their side and that evil will come to those who think it.

To the right sat the eleven members of the jury – all from Gibraltar, all men (women must volunteer for jury service but few do). Counsel shared a bench in the well of the court. On the left, Mr Patrick McGrory, the Belfast lawyer who was representing the families of the dead without a fee. In the middle, Mr John Laws, who represented the British government and its servants in Gibraltar. On the right, Mr Michael Hucker, who represented the soldiers of the Special Air Service Regiment.

The purpose of the inquest was to determine, not guilt or innocence, but whether or not the killing was lawful. The government badly needed the jury to return a verdict of lawful killing. The relatives of the deceased sought to demonstrate that the three had been murdered, and, although dealt with fairly by the coroner, they and their counsel always felt that they were at a disadvantage: inquests, unlike trials, do not require the advance disclosure of witnesses’ statements, and so McGrory had no idea what most witnesses would say before they said it. As it was the Crown’s inquest, the Crown’s counsel read the statement of every witness beforehand! Laws, therefore, could think ahead, while McGrory, always struggling to keep up, had no way of testing evidence he was hearing for the first time against what later witnesses might say.

McGrory was at a disadvantage in other respects. John Laws had been provided with ‘public interest immunity certificates’ which he invoked whenever the line of inquiry looked as though it might risk ‘national security’. So, in the public interest, the inquest learned little about the events in Gibraltar, Spain, Britain or Northern Ireland before 5 March. Nor did it ever discover the true extent of the military and police operation on 6 March, though it clearly involved many more people than appeared in court.

There was some question about who in fact would appear in the first place. Would the SAS testify? Although members of the SAS were servants of the Crown and although the Crown was holding the inquest, the government was, it said, unable to force the soldiers to come to court. Finally – with a curtain round the witness box to protect them from recognition and possible retribution from the IRA – the soldiers, voluntarily, appeared. A total of eighty witnesses passed through the court, but eighteen of them were visible only to the coroner, jury and counsel. These eighteen anonymous witnesses – referred to always by a letter – were drawn from, in addition to the SAS, MI5, Special Branch and the Gibraltar Police.

Soldier A was clearly working-class and from the south of England – perhaps London. This much could be deduced from his accent. He was also the one who fired the first shot – at Danny McCann on Winston Churchill Avenue. Soldier B was standing next to Soldier A, and subordinate to him. Soldier B was the first to shoot Mairead Farrell.

Down the street were Soldiers C and D. They were also working-class but from the north: Soldier C was probably from Lancashire. He was the first one to shoot Sean Savage. Soldier D, his subordinate, then began firing.

Two teams, then: Soldier A and Soldier B, Soldier C and Soldier D. Other teams were on the ground – the inquest heard of soldiers at the airport – but there was no way of knowing their exact number. The two ‘known’ teams reported to a tactical commander, Officer E, who was in constant touch with them via radio. Officer E reported in turn to Officer F, who was the overall commander of the military operation. Both officers spoke as though they had attended public schools.

Officer F was also assisted by a bomb-disposal expert, an Officer G. This, then, made up the SAS team:

Soldier A: the first to shoot Danny McCann.

Soldier B: the first to shoot Mairead Farrell.

Soldier C: the first to shoot Sean Savage.

Soldier D: Soldier C’s subordinate.

Officer E: the tactical commander of the two teams of soldiers.

Officer F: the overall military commander.

Officer G: the bomb-disposal expert.

There was also Mr O, a senior figure in British intelligence whose information instigated the entire operation. But in addition to the SAS there was a large number of ‘watchers’, in all likelihood drawn from MI5. At the trial their initials were H, I, J, K, L, M and N. It is probable that there were many more watchers. And finally, although most of the Gibraltar police testified without the curtain, there were three who sheltered behind it: Policeman P, Policeman Q and Policeman R.

The visible witnesses comprised the following: twenty-four members of the Gibraltar police; twelve experts on pathology and ballistics – seven from the London Metropolitan Police and two from the army; a map-maker from the Gibraltar Public Works Department; and twenty-five people who were, by accident, close to the scene of the killings. But these twenty-five people included five who worked for the Gibraltar Services Police guarding military installations, one who was an off-duty member of the ordinary Gibraltar police, one who was a former Gibraltar policeman, one who worked for the Ministry of Defence, one whose father was in the Gibraltar police, and three who worked for various branches of the Gibraltar government. No more than sixteen witnesses out of seventy-eight, therefore, could be said to be completely independent of either the British government or the administration of its dependent territory.

McGrory also had a problem with money. He had given his services free and had little to spare. The legal authorities in Gibraltar, meanwhile, had decided to charge ten times the usual rate for the court’s daily transcripts. Four days before the inquest began they raised the price from 50p to £5 per page – which amounted to between £400 and £500 per day. McGrory couldn’t afford it and instead relied on longhand notes made by a barrister colleague from Belfast. McGrory was the only person in court who wanted to ask awkward questions of the official account. But for all these reasons his ability to ask awkward questions was sometimes severely limited.

8

Over the next few weeks I sometimes wondered what Farrell, Savage and McCann made of Gibraltar during their last few hours there. Did they notice, for example, the number of fit young men in sneakers and jeans wandering aimlessly about? Did they realize that few of them were ever far away?

I wonder if they spotted the two young men lounging in the Trafalgar Cemetery. They were Soldier C and Soldier D. They were the two men who would kill Sean Savage. When Farrell looked into the Imperial Newsagency, did she see a man suddenly turn his back? He was Soldier B. Did she glimpse his face, even briefly? He was the man who would kill her. Later, walking down Line Wall Road, looking over her shoulder from time to time (which, we heard, she did frequently), did she think that the two men hurrying behind her were vaguely familiar? They were, once again, Soldiers C and D.

What about Savage? There was the chap who passed him in Lovers’ Lane. He was Policeman P of the Gibraltar police. They stared at each other, or, as Policeman P would express it to the court, he and Savage made ‘eye-to-eye contact’. Savage had been in town at least ninety minutes longer than the others, doubling back on his tracks, suddenly stopping and watching at the end of alleyways. Around two o’clock, did he see the fellow hanging about outside the Anglican Cathedral? That was Watcher H of MI5, who likewise spent the afternoon doubling back on his tracks, suddenly stopping at the end of alleyways. According to Watcher H, Savage employed ‘very subtle anti-surveillance techniques.’ All three, he said, were ‘highly alert and sensitive . . . to all the movements and events that were happening around them.’

The authorities in Gibraltar had been waiting for Savage and McCann, if not Farrell, for weeks and possibly months. The source of their information was Mr O, a senior British intelligence officer and specialist in counter-terrorism and the IRA. Mr O told the court that his representative in Gibraltar (who never appeared as a witness) had briefed the governor, the commissioner of police and military officers with details of the IRA’s intention: the time and the target, the method (car bomb), the kind of explosives that would be used (Semtex) and the names of Savage and McCann. When these details were passed on to Gibraltar’s commissioner of police, Mr Joseph Luís Canepa, Canepa then requested military assistance; the assistance would turn out to be an unspecified number of troops from the Special Air Service Regiment which specializes in covert anti-terrorist operations – most famously ambushes – in Northern Ireland.

An advisory group was then established, comprising Canepa, two of his most senior policemen, and the principal parties from Britain: Officer G, the bomb-disposal expert; Officer E, the SAS tactical commander; Officer F, the overall military commander; as well as intelligence officers from MI5. Together they devised a strategy that can be summarized as ‘arrest, disarm, defuse’. Secrecy was paramount. According to Police Commissioner Canepa, very few members of the Gibraltar police force knew of the operation. A secret operational headquarters was set up (probably in the Governor’s Residence on Main Street, though the location was never revealed to the inquest). There, at midnight, between 5 and 6 March, a meeting of police, military and intelligence officers was told that the three suspects were in Spain and that they could be expected to arrive during the next forty-eight hours.

A secret operational order was issued.

Soldiers and police were briefed about how they would put the order into effect. First, the offenders would be arrested, ‘using minimum force’; second, they would be disarmed and their bomb defused; then evidence would be gathered for a court trial. SAS soldiers would make the arrests and hand over the suspects to armed Gibraltar policemen.

By this stage, the operation had a codename, ‘Operation Flavius’. The order for Operation Flavius had many appendices, the most vital being the rules of engagement. The written instructions that Officer F, the overall military commander, was meant to obey included the following:

use of force

You and your men will not use force unless requested to do so by the senior police officer(s) designated by the Gibraltar police commissioner; or unless it is necessary to do so in order to protect life. You and your men are not then to use more force than is necessary in order to protect life . . .

opening fire

You and your men may only open fire against a person if you or they have reasonable grounds for believing that he/she is currently committing, or is about to commit, an action which is likely to endanger your or their lives, or the life of any person, and if there is no other way to prevent this.

firing without warning

You and your men may fire without a warning if the giving of a warning or any delay in firing could lead to death or injury to you or them or any other person, or if the giving of a warning is clearly impracticable.

warning before fire

If the circumstances in [above] paragraph do not apply, a warning is necessary before firing. The warning is to be as clear as possible and is to include a direction to surrender and a clear warning that fire will be opened if the direction is not obeyed.

Those were the rules. Here, once again, are the facts. Farrell, Savage and McCann were unarmed; the car Savage had driven into Gibraltar did not contain a bomb; all three were shot dead. Can the facts be made to square with the rules? Can the facts be reconstructed or revealed in a new light, as it were, which would make their pattern on 6 March conform with the law? The recent history of Northern Ireland supplies an answer.

9

Soldiers of the SAS were first dispatched to Northern Ireland in 1976 by the then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Merlyn Rees. This year Rees admitted that their deployment had as much to do with public relations as counter-terrorism: the Labour government needed to be seen to be ‘getting on top of terrorism’, and the piratical, daredevil reputation of the regiment, familiar only to students of late colonial counter-insurgency (Malaya, Borneo, Aden), might therefore be fostered to appease public concern. ‘Who Dares Wins,’ says the regimental motto. The SAS could be expected to strike first.

Two years later, on 11 July 1978, an SAS unit shot and killed a sixteen-year-old boy, John Boyle, at a cemetery near his home in County Antrim. The previous day Boyle had discovered an arms cache in the cemetery and told his father, who then informed the Royal Ulster Constabulary. The RUC passed on the information to the army, who then ‘staked out’ the cemetery with soldiers from the SAS. The next day young Boyle was cutting hay in a field near the cemetery and at about ten in the morning went back to see if the arms were still there. The SAS opened fire. Boyle’s father, meanwhile, had been warned by the RUC about the stake-out. He ran to the graveyard to look for his son and was joined by Boyle’s elder brother, who had also been haymaking in another field. The SAS arrested both men. The army’s press office quickly issued a statement: ‘At approximately 10.22 a.m. this morning near Dunloy a uniformed military patrol challenged three men. One man was shot; two men are assisting police enquiries. Weapons and explosives have been recovered.’

The SAS version of events did not please the RUC. The Boyles were a Catholic family and therefore an unusual and prized source of important information. The SAS had now shot one of the family dead. In its press statement, the police denied the army’s implication that the Boyles were connected with terrorism, prompting a second army statement confessing to inaccuracies in the first: ‘Two soldiers saw a man running into the graveyard. They saw the man reach under a gravestone and straighten up, pointing an Armalite rifle in their direction. They fired five rounds at him. The rifle was later found with its magazine fitted and ready to fire.’

There had been no challenge – a warning would have been ‘impracticable’.

Eight months later, in the wake of a public outcry caused by the publication of the pathologist’s report, two SAS soldiers were charged with murder. Evidence at their trial showed that the rifle had not been loaded, contrary to the army’s second statement, and the judge was unable to decide if Boyle had ever picked it up. He concluded that the army had ‘gravely mishandled’ the operation and that the only SAS soldier to give evidence – one of the two charged – was an ‘untrustworthy witness’ who gave a ‘vague and unsatisfactory’ account. The two were found not guilty none the less. Their ‘mistaken belief that they were in danger,’ said the judge, was enough to acquit them.

Over the past fifteen years many other killings in Northern Ireland have hinged in court on this question of ‘mistaken belief’ and the subsequent use of ‘reasonable force’. Perhaps the most famous is the case of Patrick McLoughlin, who was shot dead with two other unarmed men as they tried to rob a bank in Newry in 1971. McLoughlin’s widow, Olive Farrell, sued the Ministry of Defence for damages in the Northern Ireland High Court, but the jury decided that McLoughlin was to blame for his own death. It had been persuaded by the argument that British troops, in a stake-out or ambush similar to the one that killed Boyle, had shot three men because their commanding officer had suspected, ‘with reasonable cause’ (though wrongly), that the three were trying to plant a bomb which would endanger life. Shooting was the only practicable, and therefore reasonable, means of arrest. As Lord Justice Gibson, the Northern Ireland judge later to be killed by a republican bomb, commented:

In law you may effect an arrest in the vast extreme by shooting him [the suspect] dead. That’s still an arrest. If you watch Wild West films, the posse go ready to shoot their men if need be. If they don’t bring them back peaceably they shoot them and in the ultimate result if there isn’t any other way open to a man, it’s reasonable to do it in the circumstances. Shooting may be justified as a method of arrest.

The case of Farrell versus the United Kingdom was appealed unsuccessfully in the House of Lords and went eventually to the European Commission on Human Rights, where the British government settled out of court in 1984 by paying Farrell £37,500. The payment ensured that the commission’s ruling remains confidential, though the British government’s submission to the commission has been published. Britain argued that the jury in the Farrell case had been directed correctly because it had been told that it would be unreasonable to cause death ‘unless it was necessary to do so in order to prevent a crime or effect the arrest’; and that the concepts of ‘absolutely necessary’ and ‘reasonable’ were the same thing when it came to killing a person believed to be a terrorist bomber.

‘Belief’, ‘believed’, ‘reasonable’. The same words appear in Operation Flavius’s rules of engagement. The inquest heard them with dripping regularity. Out of the graveyards of Ulster, one may suspect, reasonably, came the bones of the government’s legal case in Gibraltar; a case, like Boyle’s and McLoughlin’s, of mistaken belief.

10

Could there really have been a bomb activated by a button?

In the months preceding the inquest, the Sunday Times became essential reading if only because its reports seemed to reflect so reliably the official leaks that served to strengthen the government’s original story: that Farrell, McCann and Savage had all made ‘suspicious movements’ – suspicious enough to justify shooting the three of them: either they were going for guns or they were about to detonate a bomb with a radio-controlled device. That they had neither guns nor radio-controlled devices obviously diminished the credibility of the government’s story, which was diminished further following the statements made for the Thames Television programme by bomb expert George Stiles: that he had never known the IRA to explode a radio-controlled bomb without a view of the target, and that it was unlikely in the extreme that the kind of transmitter used by the IRA could have been sophisticated enough to send a signal a mile from the bomb with buildings in between.