February 1914, Salzburg

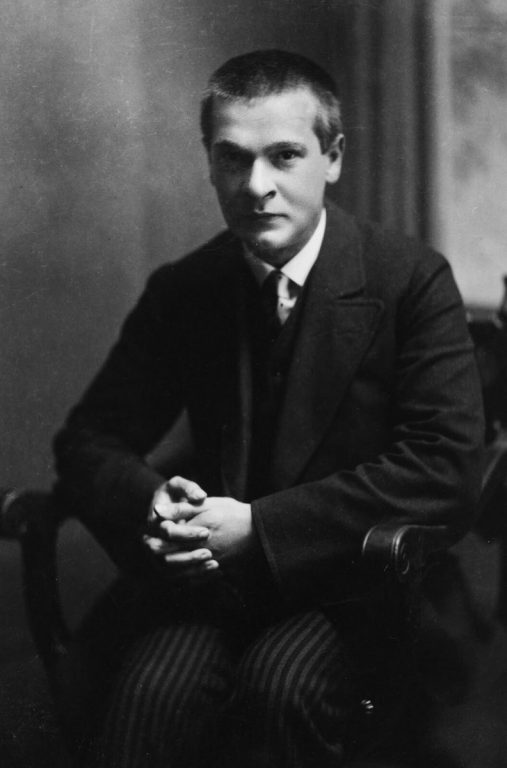

This is the last series of portraits we have of him. Half the face in shadow. Child’s features. Shadow and child – thick eyebrows, black as clouds, weighing heavily over his eyes. A gaze of storm, of wind-tossed forest, at twilight. A narrow mouth, well-defined; thin lips, their corners turned slightly downward. A strong crease swells the cheek like a mask. Fingers interlaced, hands folded. Seated in a wooden armchair – we can glimpse its scroll under his left elbow. Shadow and child. Dark trousers striped with dark, hair crew-cut very short. Fear, mute anguish, or impatience and anger – hard to decide, but Georg Trakl doesn’t look very pleasant in this photograph. Moon-face. A 27-year-old moon-faced child. A child on drugs, a drunk child, a guilty child, a child looking for Death by any means. Death, the last forgiveness. A child poet.

This photograph might resemble the portrait Oskar Kokoschka would have painted of Trakl at the time if he had had the time, if the war hadn’t given Georg the opportunity to die. The portrait will be posthumous, based on the artist’s memories, and Trakl will look much older – forty, fifty years old, with marked features. Georg frequented Kokoshka’s studio in Vienna after Kokoshka returned from Berlin at the start of 1912 – Georg sought his colleagues, authors, poets, painters.

The young man from Salzburg had chosen a dangerous profession for himself – the pharmacy. The pharmacy easily provided him with barbiturates, opium, cocaine, so many instruments of finality. Ways to do away with yourself. Ways to begin exploring the shadow, the imaginary boundless winter forest. Schlaf und Tod, sleep and death, Hypnos and Thanatos, Heinrich Heine’s two deadly brothers sit at his side – those two eagles with bowed heads will accompany Trakl all his life.

We think we see Georg Trakl in this last photograph but we do not see him. No one actually knows who he is, aside perhaps from his sister Margarete, whom he calls Gretel. Georg will remain in obscurity. His long reveries, his imaginary strolls in autumnal decay, his damaged personas in the mists of solitary suffering. Meanwhile, Kaspar Hauser, dead with his enigma. At night he remained alone with his star. And in the twilit hallway, the shadow of his murderer. Silver sinks down the head of the unborn.

Kaspar Hauser, the child of Europe, they said, speaking of his high and mysterious birth; Georg Trakl the child of Europe, son of poetry, of literature, son of the coming Apocalypse. This generation, the generation of those called ‘Expressionist’ or ‘avant-garde’, spoke before the catastrophe; they were the Prophets of the massacre still to come, they described the end of a world without necessarily surviving it. Georg Trakl is like that, child of this language that bathes the field of the dead, oarsman rowing on a canal against the flow, beneath the indifference of the stars.

March 1914, Berlin

Margarete the beloved sister is in the hospital in Berlin, after a miscarriage and a terrifying haemorrhage. She has been married for some years to a man thirty-four years older than she, Arthur Langen. Georg makes the journey from Austria to see her. They don’t know it but this will be their last meeting. Legend has it that Trakl is convinced her dead child is his. His sister does not contradict him. The two young people have always loved each other, with a sombre love that cannot live in the light. A selenic passion, with the darkness of the new moon. The Sister haunts his texts. The blood of the sister, the melancholy of the sister, the guilt of Georg. Such a love can only be encoded. It grew in secret in childhood, developed in adolescence. That’s what we imagine. Isis and Osiris giving birth to Horus. That would be too simple. They give birth only to their own suffering. The sister with the furious sadness, the one who haunts (skiff on the waves, hidden by the silence of night) the poet’s body and memory. Of this passion there remain only flashes hidden in Trakl’s verses. Glimmering sighs. Their letters were destroyed, their love could bear no fruit, no words or recollections. Transgression, abandonment, silence instead of the lightning-flashes of pleasure, the tornadoes of the flesh.

Images of the time show us Margarete Trakl with a pale face, a strong nose, a fine head of dark hair. The disturbing thing is her resemblance to her brother. A resemblance that they themselves may not have seen, but that the black-and-white photograph emphasizes. If any of that is true.

We do not know if it was to escape that bitter love that, in Salzburg and later in Vienna, Trakl hurried every night into brothels, into the thick somnolence of ether or the blind energy of cocaine. Ever since he reached the age of reason, Georg has fled. He gives himself terrifying quantities of wine and equally great numbers of prostitutes. Salzburg is a small town of merchants and soldiers trapped in the memory of Mozart. Trakl père, Tobias, is an ironmonger. Business is profitable. The Trakl couple have six children, including Georg and Grete. Georg says he always hated his mother, hated his mother to the point of wanting to strangle her with his own hands. He prefers the Alsatian governess with whom he speaks French. Georg takes refuge not just in alcohol and drugs but in poetry as well. He reads Rimbaud, Verlaine. He pictures himself as Rimbaud’s ‘voyant’, a seer practicing All forms of love, suffering, madness. Suffering and secret madness that Grete, we imagine, shares with him. We know nothing of any of this. We just know she is a gifted pianist and that her Berlin husband ends up demanding a divorce, on the grounds of adultery, with two of Georg’s closest friends.

Margarete Trakl is the blind spot – the corner all the critics, all the curious have wanted to invade. The secret corner. Three years after her brother’s death, in 1917, in Berlin, Margarete Trakl shoots herself in the heart. Everything plunges into uncertainty. Of these two beings, of the power of what joined them, there remain only the ripples on the surface of water, the stains on the moon, the rustle of the leaves in Georg’s poems, the complex arpeggios of Grete and the sound of a gunshot.

April 1914, Venice

Everything moves irresistibly towards the end. A certain Europe, several Empires and Georg Trakl. Georg, who of course is nothing but an accident, only one of the possible configurations of humankind. One of the possible monstrosities of humankind. Mysterious, drugged, incestuous. Everything moves towards the end and towards decomposition. Cities decompose, civilizations totter towards ruin, forests are nothing but immense factories of rot. Venice is rot itself. The city of gangrene. The Republic of haggling, furs and firearms. On the grey beach of the Lido we see Georg Trakl (Dear friend! The Earth is round. I’m letting myself fall towards Venice. Ever further away – towards the stars), Adolf Loos and Karl Kraus. They wear those bathing suits with braces fashionable at the time and are having their picture taken. Loos the 44-year-old architect: he published Ornament and Crime a few years before and has his hands full with projects. Kraus, publisher of the newspaper Die Fackel (The Torch), has published a few texts by Trakl. Ludwig Ficker, publisher of the journal Der Brenner (The Burner), also comes from Innsbruck to spend a few days in Venice. The friends drink, swim, write. Georg writes among a cloud of black flies, watching the death throes of the day gilding age-old stones. Georg, in a foreign country, feels as if he has lost his homeland, the homeland. Motionless, the sea turns dark. Star, blackened journey, vanished in the canal.

Everything is rushing to its tepid loss.

September 1914, Gródek

Perhaps catastrophe isn’t pointless. With Trakl everything comes to that, everything announces it, everything prepares for it. But before coming to the long plains of Galicia I would like to evoke another portrait, another future sketch, a remote one this time. We saw that in May 1914 Georg was at his sister’s bedside on Grolmanstrasse in Berlin, close to Savignyplatz. He had also gotten close to another woman’s face, that of Else Lasker-Schüler, a few streets further down; she had just fallen in love – no, not with Georg Trakl – but with another round-faced young man, a doctor by the name of Gottfried Benn. The doctor and pharmacist. Benn had just written about his experiments with dissections at the pathological institute, the hundreds of more or less rotting bodies he had cut apart, sliced open. He published Morgue in 1912. He would be a medico in the Belgian campaign. He would live to be relatively old and would die in the 1950s in this twentieth century that Trakl just barely saw get underway. Benn would have the time to grow interested in distant islands, in the colour blue, in theory; Benn would carry his intransigence pretty much everywhere around him; Benn would look Nazism in the eye before spitting in its face. Benn would return to Trakl in his last collection, Aprèslude, in 1955 – at least that’s the impression I have – in the last two pieces in this last collection, I think, ‘Last Spring’ and ‘Aprèslude,’ two poems that might be remembering (especially ‘Last Spring’) Georg Trakl who died forty years earlier, mad, thin and evanescent, blue, actually, Georg Trakl with whom Benn had gotten drunk in Berlin in the company of Else Lasker-Schüler who wasn’t the last to raise a glass, not at all, she drank with an entirely Nietzschean devotion, like Benn himself, and it wouldn’t take much, thought Gottfried Benn, for those two to fall in love, the drunken Austrian and the subtle Jewish lady, the powerful woman who was searching for herself, was questioning herself at the bottom of glasses, at the bottom of dozens of glasses that she drank without respite in that perfect Berlin, that Berlin that had not yet been sullied by the Revolution, just by the clap, and Benn thought about his own observations of Berlin’s syphilitic cankers, scruffy bodies, opened up from neck to rump, that released their green effluvia in swarms of dead flies drowned in nauseating formaldehyde, one more little drink, thought Benn, a caryatid for Bacchus, this Jewess gone with this Austrian, Austrians have always seemed to me to have a two-faced way of talking, a phony accent, a singular affectation like Trakl with the broad shoulders who didn’t at all have a poet’s sickly physique, how delightful, a well-built upright guy, a sturdy fellow who drinks as you should, with abundance and regularity, but who is also subtle and well-versed in letters, in the transformation of letters, too bad he doesn’t live in Berlin, or maybe all the better, haha, you never know, I do know (Benn still thought, pouring himself another drink) that Else will be sad when he dies, this Trakl, that she was sad when he died, she wrote two magnificent texts for him, for the Austrian poet passing through Berlin who raised a glass as well as she, for the Austrian poet with the broad shoulders, for the Austrian poet of the autumn landscapes, of the moon’s reflections and of deadly trees, our fate, those 75 mm shells, entrails, the twisted trees of our skeletons, come, come see these corpses they gleam, they shine, they burst, I was a doctor, said Gottfried Benn much later still in Berlin, I was a doctor in Belgium but I did not see the front – our Georg Trakl saw the front, the wounds, the open mouths of the dead, a guy who comforts himself with a pistol shot right in the face, a guy whose brain spangles your gaze, the wall, we comfort ourselves, here, I’m suffering too much I’ll go away, I scatter my brain like a God, offal, you look without seeing the groans of molars in the wide-open shout, I spread my brain, I’m sending it to you, it’s a slap of shame, you’re moaning, you’re crying, we are in the infinite plain of Gródek, the infinite plain of . . . Calm. A little time. Georg looks at Else Lasker-Schüler. He stares at her. It’s Berlin and it isn’t yet death, the cold night of the trees of Berlin, the numbers on the buildings at night in Berlin, the women of Berlin, the alluring clothes of the women of Berlin, the shouts of Dionysus which are the cries of Berlin.

Georg Trakl goes off to war. Summer 1914. Almost fall. Only two poems left.

Georg Trakl goes off to war. And he leaves for a very Austrian war, not at all Berlin-like, so Austrian we don’t know what to call it, Austro-Hungary fights against the Russians at the edge of their Empire, in the Galician plain, on the Lemberg side, today Lviv, in the Ukraine. A crow-filled plain, furrows to plant the dead.

Let’s try to leave aside the lyricism, the time, the century gone by. Let’s forget death and the poetry that comes with death. It is hard to feel reconciled with his final disappearance. Those broad shoulders, those precise, strong legs, that bushy gaze. A few more verses and he is no longer alive. Adieu. My sister is still living, but she is dead. My brother is living, but he will die. Adieu. You will see forests, you will experience storms. You will be the wounded man of the century. You have imagined immense monuments under the victors’ eagles, indisputable, ever-increasing legions, whose pinions would shelter your wanderings – or extinguish them. The Empire was about to lie down in this rut and suffer this plain like a cry. Scarcely having entered the war, we die. Immediately we return to Georg Trakl. To his uniform, to his helmet. There where we’re in the midst of flesh and fear, in a barn with ninety-nine wounded soldiers to care for. I see them, I hear them. They’re shouting. I bandage them they shout louder, they want nothing but death which doesn’t come quickly enough, we are in a barn on straw I am the doctor I am the caregiver you are thirsty your intestines are throbbing, the wound in your stomach touches the ground I see the thick white spirals of your intestines don’t drink, don’t drink, I’d like to be able to take my gun and end these convulsions, these convulsive recollections, in this barn on the straw I can’t look at your uniform your insignia your blood what is your name, what is your name, this is how they appear the wounded of the Barn at Gródek, so many mouths smashed in open cries, all roads lead to black decay.

And there, on the eve of death, at the instant of dying, at the instant of the last poem, the shadow of the sister mingles again, like a perfume, with the dark waves of trees; she’s the one who comes to greet the bloody ghosts of the fallen heroes.

3 November 1914, Totenschein

From an overdose of cocaine

They say you gave yourself death

In the military hospital of Kraków.

A telegram announced it

In Berlin

And in Salzburg:

‘Georg died

The night of 3-4 November

At the military hospital of Kraków

Of a heart attack

On the 6th buried

At the military cemetery

In the same place

Condolences’

You gave yourself death

Or she took you

Gave to death

There follows a long winter of silence

Finally joined in the womb

The twins

Sleep and Death.