My father wrote a kind of autobiography in the years before he died. I have it now beside me in a big brown paper envelope, 150 pages of lined foolscap covered with the careful handwriting – light on the upstroke and heavy on the down – which he learned on a slate in a Scottish schoolroom eighty years ago. He called these pages ‘a mixture of platitudes and personal nostalgia’.

My father’s life spanned eight decades of the twentieth century, but he met nobody who mattered very much and lived far removed from the centre of great events. He was born in the year the Boer War ended, in a mill town in the Scottish lowlands. A Co-operative Society hearse took him to a crematorium in the same town six months before Britain fought what was probably the last of its imperial wars, in the Falklands. He was too young for the Somme and too old to be called up for El Alamein. He never saw the inside of Auschwitz and knew nobody who did. He neglects to tell us his role (if any) in the General Strike. He worked for most of his life as a steam mechanic (though he always used the word ‘fitter’); a good one, so I have been told by the people who worked beside him.

He started work as a fourteen-year-old apprentice in a linen mill on five shillings a week and progressed through other textile factories in Scotland and Lancashire, into the engine room of a cargo steamer, down a coal pit, through a lead works and a hosepipe factory. He loved applying for jobs – would study the advertisements, remove the cap from his fountain pen, rest the lined foolscap on a chessboard he had made for himself, and write steadily in an armchair near the fire – and only fate in the shape of unwelcoming managements prevented his moving to work in jute mills on the Hoogli or among a colony of French progressive thinkers in the South Pacific.

He did not prosper. Instead he ended his working life a few miles from where he began it, and in much the same way: in overalls and over a lathe and waiting for the dispensation of the evening hooter, when he would stick his leg over his bike and cycle home. He never owned a house and he never drove a car, and today there is very little public evidence that he ever lived.

Few of his workplaces survive. The cargo steamer went to the scrapyard long ago, of course, but even the shipping line it belonged to has vanished. The coal pit is a field. Urban grasslands and car parks have buried the foundations of the mills. The house he grew up in has been demolished and replaced with a traffic island. The school where he learned his careful handwriting has made way for a supermarket. As a result, I am one of the sons of the manufacturing classes whom de-industrialization has disinherited; in many respects it is a benign disinheritance, because many of the places my father worked were hell-holes, but it is also one so sudden and complete that it bewilders me.

Still, there is this ‘mixture of platitudes and personal nostalgia’. But I’m exaggerating the paucity of what he left behind. There was actually much more than the contents of the brown envelope. There were books, suits from Burtons, long underpants, cuff links, shirt armbands, pipes which continued to smell of Walnut Plug, the polished black boots he always preferred to shoes, half-empty bottles of Bay Rum, tools in toolboxes, shaving brushes, cigarette cards, photograph albums, photographs loose in suitcases, tram tickets, picture postcards sent from seaside resorts and inland spas – Rothesay and Llandudno, Matlock and Peebles. Here for the week. Weather mixed. Lizzie and Jim. What a man for collecting! Even here, interleaved among the foolscap, I find a card from the Cyclists’ Touring Club for the Christmas of 1927, a bill from the Spring Lodge Hotel (family and commercial) for sixteen shillings and fourpence and a menu from the mess of the cargo steamer Nuddea dated 12 October 1928 (that day’s lunch, somewhere in the tropics, comprised pea soup, fried fish, roast sirloin of beef). And in a smaller envelope inside a larger one is a pamphlet on humanist funeral ceremonies, for ‘when it is desired that no reference should be made to theological beliefs but, rather, to the ethical and natural aspects of human life’.

He left no explicit instructions, but the hint is clear enough. We only half-obliged. We did not stand at the lectern and read aloud, from the scraps of card which tumble from this smaller envelope:

I want no heaven for which I must give up my reason and no immortality that demands the surrender of my individuality.

Or:

Forgive me Lord, my little joke on thee

and,

I’ll forgive your one big joke on me.

The truth is that a strident proclamation of my father’s doubt would have sat strangely out of kilter with the last quarter of the twentieth century in Britain. Who, in this country of the don’t-knows, now doubts doubt? It would have been like listening, that day in the crematorium, to the proposition that the earth moved round the sun.

I was born in 1945 and grew up in the Scotland of the 1950s. But in our house we lived in the 1910s and 20s as well, concurrently. The past sustained us. It came home from work every evening with flat cap and dirty hands and drew its weekly wages from industries which even then were sleepwalking their way towards extinction.

Our village lay at the northern end of the Forth Bridge, three large cantilevers which had been built with great technical ingenuity, and at some cost to human life, to carry the railway one and a half miles over the Firth of Forth. It was opened by the Prince of Wales in 1890. The village was unimaginable without the bridge. Its size reduced everything around it to the scale of models: trains, ships, the village houses – all of them looked as though they could be picked up and thrown into a toy cupboard. The three towers rose even higher than our flat, which stood in a council estate 250 feet above the sea. On still summer mornings, when a fog lay banked across the water and the foghorns moaned below, we could see the tops of the cantilevers poking up from the shrouds: three perfect metal alps which, when freshly painted, glistened in the sun. Postcards sold in the village post office described the bridge as the world’s eighth wonder, and went on in long captions to describe how it had been built. More than 5,000 men had ‘laboured day and night for seven years’ with materials which included 54,160 tons of steel, 740,000 cubic feet of granite, 64,300 cubic yards of concrete and 21,000 tons of cement. They had driven in 6,500,000 rivets. Sixty workers had been killed during those years, some blown by gales into the sea and drowned, others flattened by falling sheets of steel.

For several decades the bridge dazzled Scotland as the pinnacle of native enterprise, and then slowly declined to the status of an old ornament, like the tartan which surrounded its picture on tea towels and shortbread tins. People of my father’s generation had been captivated by its splendour and novelty. Pushing his bike as we walked together up the hill, he would sometimes say ruefully: ‘I became an engineer because I wanted to build Forth Bridges.’

From quite an early age I sensed that something had gone wrong with my father’s life, and hence our lives, and that I had been born too late to share a golden age, when the steam engine drove us forward and a watchful God was at the helm. Scotland, land of the inventive engineer! Glasgow, the workshop of the world! I hoped the future would be like the past, for all our sakes.

My father began his apprenticeship in 1916 in one of Dunfermline’s many linen mills. The town was famous for the quality of its tablecloths and sheets – ‘napery’ used to be the generic word – and ran along a ridge with a skyline spiked by church steeples and factory chimneys. The gates of my father’s first factory were only a few hundred yards from his home. He writes:

We oiled and greased and greased and oiled … pirn winding frames, bobbin winding frames, cop winding frames, overpick and underpick looms, dobbie machines, beetles, calenders and shafting. There was never an end to shafting! A main shaft approximately 250 feet in length driving thirty-two wing shafts of an average length of seventy-five feet. This was all underfloor … and eight of these wing shafts had to be oiled every day when the engine stopped for the mill dinner hour.

Later he moved to the blacksmith’s shop, where he made ‘hoop iron box-corners’ for the packing department and learned how to handle a hammer and chisel. ‘Chap, man, chap!’ said the blacksmith. ‘Ye couldnae chap shite aff an auld wife’s erse.’ Eventually, towards the end of his apprenticeship, he was transferred to the engine house:

Sometimes I would be allowed to attend the mill engine for a week or a fortnight … taking diagrams from each cylinder with an old Richards Indicator, and studying the cards, I felt just as a doctor must feel when sounding his patient’s lungs with a stethoscope. If the cards were all right and the beat of eighty-five revs per minute had become automatic listening, then I could relax, and, as smoking was just tolerated in the engine house, have a Woodbine. It is said that the ratio of the unpleasant to the pleasant experiences in life is as three to one. The engine ‘tenting’ [tending] was one of those pleasant intermissions.

Reading this, I try to construct a picture of my father thirty years before I knew him. There he sits next to the cascading, burnished cranks of the mill engine. I know from snapshots that he has curly black hair and a grave kind of smile. Perhaps he’s reading something – H. G. Wells, a pamphlet from the Scottish Labour Party, the Rubáiyáe of Omar Khayyam. The engine pushes on at eighty-five revolutions per minute. Shafting revolves in its tunnels. Cogs and belts drive looms. Shuttles flash from side to side weaving tablecloths patterned with the insignia of the Peninsular and Oriental Steamship Company and the Canadian Pacific Railway. Stokers crash coal into the furnaces – more heat, more steam, more tablecloths – and black clouds tumble from the fluted stone top of the factory chimney, to fly before the south-west wind and then to rise and join the smoke-stream from a thousand other workplaces in lowland Scotland: jute, cotton and thread mills, linoleum factories, shipyards, iron-smelters, locomotive works. Human and mechanical activity is eventually expressed as a great national movement of carbon particles, which float high across the North Sea and drop as blighting rain on the underdeveloped peasant nations to the east.

In 1952, after twenty-two years working in Lancashire, my father returned to Scotland, to his old factory. It was his tenth move, and a complete accident: the result of yet another letter to an anonymous box number underneath the words ‘Maintenance Engineer Wanted’.

My mother, surrounded by people who called her husband Jock (his name was Harry) and talked of grand weeks in Blackpool, had fretted to be home among her ‘own folk’, but my father hadn’t minded Lancashire. He liked to imitate the dialect of the cotton weavers and spinners; it appealed to his sense of theatre, just as the modest beer-drinking and the potato-pie suppers of the Workers’ Educational Association sustained his hope that the world might be improved, temperately. The terraced streets shut my mother in, but my father, making the best of it, found them full of ‘character’: men in clogs with biblical names – Abraham, Ezekiel – and shops that sold tripe and herbal drinks, sarsaparilla, and dandelion and burdock. He bought the Manchester Guardian and talked of Lancashire people as more ‘go-ahead’ than the wry, cautious Scotsmen of his childhood. Lancastrians were sunnier people in a damper climate. They had an obvious folksiness, a completely realized industrial culture evolved in the dense streets and tall factories of large towns and cities. Lancashire meant Cottonopolis, the Hallé Orchestra playing Beethoven in the Free Trade Hall, knockers-up, comedians, thronged seaside resorts with ornamental piers. In Fife, pit waste encroached on fishing villages and mills grew up in old market towns, but industry had never completely conquered an older way of life based on the sea and the land.

Later he would talk of Bolton as though he had been to New York, as a place of opportunity, with witty citizens who called a spade a spade. A Lancashire accent, overhead on a Scottish street, would have him hurrying towards the speaker. Often he was disappointed:

‘Do you mind me asking where you’re from?’

‘Rochdale.’

‘Och, I’m sorry, I thought it might be Bolton.’

We moved back to Fife. The furniture went by van while we came north by train, behind a locomotive with a brass nameplate: Prince Rupert. I was seven. I held a jam jar with two goldfish, whose bowl had been trusted to the removers, as Prince Rupert hauled us over the summits of Shap and Beattock. The peaks and troughs of telegraph wires jerked past like sagging skipping ropes. Red-brick terraces with advertisements for brown bread and pale ale on their windowless ends gave way to austere villas made of stone. The wistfulness of homecoming overcame my parents as we crossed the border; Lancashire and Fife then seemed a subcontinental distance apart and not a few hours’ drive and a cup of coffee on the motorway. Our carriage was shunted at Carstairs Junction and we changed stations as well as trains in Edinburgh. Here English history no longer provided locomotive names. We had moved to new railway territory, with older and quainter steam engines named after glens, lochs and characters from the novels of Sir Walter Scott. At dusk we sped across the Forth Bridge behind an Edwardian machine called Jingling Geordie, sailing past our new home and on towards the small shipbuilding town where my mother’s father had settled.

When I awoke the next morning rivetters were already drilling like noisy dentists in the local shipyard, and express trains drifted, whistling, along the embankment next to the sea. The smells of damp steam and salt, sweet and sharp, blew round the corner and met the scent of morning rolls from the bakery. Urban Lancashire could not compare with this and, like my mother, I never missed it. But what was linear progress for a seven-year-old may have been the staleness of a rounded circle for a man of fifty: this little industrial utopia of my childish eye had foundations which were already rotting.

Two days later we moved a few miles down the coast and into our home beside the Forth Bridge, and my father went to work in his new-old factory. It was a shock:

The scrap merchants were at work; they had removed most of the looms and machinery from the old weaving shed, which made it a most cheerless place. The blackbirds were nesting in the old Jacquard machines. All the beam engines had gone and the surface condenser on top of the engine house in the mill road was now standing dry and idle. The latest engine (installed in 1912) was a marine-type compound; it was also standing idle with the twelve ropes still on the flywheel. The engine packing and all the tools were still in the cupboard, the indicator, all cleaned, lay ready to take diagrams; there was even a tin of Brasso and cloths for polishing the handrails. It seemed as if everything was lying in readiness for an unearthly visitor to open the main steam valve. But there was no steam, everything was cold and silent …

The views from our new house were astounding. On the day we moved in, in October 1952, I stood at the top of the outside stair and watched a procession of trains crossing the bridge and a tall-funnelled cargo steamer passing below, unladen and high out of the water, its propeller playfully flapping the river. Pressing my nose against the front-room window and squinting to the left I could see Edinburgh Castle. In Lancashire all we could see from our windows were back gardens and washing and more houses like our own, with all the doors painted in council green. My parents’ phrase, ‘moving up home to Scotland’, took on a literal meaning. It was as though we had been catapulted from a pit bottom into daylight.

In 1956, the summer before Suez, my father took us to Aberdeen. It was my first proper holiday and the first evidence, perhaps, of a slightly increased disposable income: all previous excursions had been to the homes of aunts and grandparents. That spring we studied the brochures which declared Aberdeen ‘the Silver City with the Golden Sand’, and the word ‘boarding house’ became part of the evening vocabulary. My father chose a name and address and corresponded with the landlady. My mother didn’t like the sound of it: she noticed that the address did not carry the distinguishing asterisk which marked the approval of Aberdeen’s town hall. But my father tutted and persisted: it would be fine; the landlady sounded a nice wee woman. We went by train (an express; high tea in the dining car) and then by bus to a grey suburb in the lee of a headland where the North Sea sucked and boiled. It quickly became obvious that the house was ‘off the beaten track’, a phrase and a situation which always recommended themselves to my father. It lay a change of buses away from the beach but very close to a fishmeal factory. The smell of rotting fish hung over the street and crept into the house, to slide off the polished Rexine of the sofa and chairs but impregnate permanently the dead collie dog which the landlady had converted into a rug. The whiff of more marine life, cooking in pots, came from the kitchen. We ate boiled and fried haddock for a week and were reminded constantly that Aberdeen was then the premier fishing port of Europe. This was twenty years before the oil came in.

At night I shared a room with a young man who had an institutional haircut and dug for a living in a market garden. Other young men, equally shorn, emerged for the breakfast kippers. Mrs MacPhail, the widowed landlady, had claimed them after they had reached the age limit of the ‘special schools’ that contained them during adolescence. On the first morning we walked to the lighthouse and stared forlornly across the harbour mouth towards the inaccessible beach. My father said we would just have to make the best of it; the other lodgers were ‘decent enough laddies … a wee bit simple but hardly proper dafties … there’s no harm in them’. And there wasn’t. On wet evenings the hardly-dafties took me to the cinema, and on the night before we left they gave us a concert in the room with the dog rug. My room-mate, Johnny, sang ‘If I Were a Blackbird I’d Whistle and Sing’. Another hummed ‘A Gordon For Me’ through a comb and paper. A third placed a favourite new record on the radiogram and again and again we heard: ‘Zambezi! Zambezi, Zambezi! Zam!’ The next morning my father – who had a terrible fear of missing trains – rose at an extraordinarily early hour to pay the bill and surprised the landlady, naked and trying to cover herself with the remains of her pet collie.

More than twenty years later, he would mention the experience whenever the word Aberdeen looked likely to occur in a conversation, even if the rest of us had been talking about the oil rigs now moored in the firth outside the house, or what would happen to the country when the oil ran out.

My father went on cycling back from his lathe until well into the 1960s. The new decade was good to us both. I left home at eighteen and gladly entered pubs, football grounds and dance halls. Films and television plays began to represent British life as we thought we knew it. When Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, the film of Alan Sillitoe’s novel, came to the local Regal, I was thrilled to see scenes of conscientious men working at milling machines and lathes. ‘Poor bastards,’ says Albert Finney in the role of the new British hero, the young worker who sticks up two fingers at respectability and grabs what he can get.

The film kindled a suspicion within me that this was the definitive verdict on my father, apparently a dupe who had worked for buttons for nearly fifty years. It was an ignorant, adolescent judgement: my father was not a ‘poor bastard’ and surprising things began to happen to him. I came home late one Saturday night and found him roaring with laughter at a satire show on television. He joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and worked for it long after I, an earlier but more faint-hearted member, had left. He won a couple of thousand pounds on the football pools (a total ignorance of football led to the correct forecast; virtue, for once, had its reward) and took my mother on sea voyages to Egypt and the Soviet Union, two countries which had fascinated him since Howard Carter found Tutankhamen’s tomb and the Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace. He grew jollier and, rather than offering bitter homilies against masonic foremen and the unfairness of piecework, settled into a new role as a teller of quaint stories.

In 1967 he retired with a present of twenty pounds in an envelope and a determination to enjoy himself. He read books on Egyptology, went to evening classes in Russian, cultivated his garden and watched quiz shows and documentaries on television. This is the passage of my father’s life I know least about. Somehow we missed our connection. I neglected him, no longer went out with him on the bike, barely listened to the stories I thought he would always be there to tell.

As the old died the village filled up with new people: wives who wore jeans and loaded small cars at the nearest supermarket, husbands who drove what twenty years before would have seemed an impossible distance to work. Couples gutted old cottages and painted knock-through rooms in white, hung garlic from their kitchen shelves. In these houses ‘lunch’ and ‘supper’ supplanted ‘dinner’ and ‘tea’, but their owners, searching for a past to embellish their modern lives, went burrowing into history to uncover village traditions which had been invisible for forty years. The only village celebration of my childhood had been the one to mark the Coronation, when New Testaments and children’s belts in red, white and blue had been distributed. Now an annual gala day was revived, with a bagpiper at the head of the procession, and a ‘heritage trail’ signposted in clean European sans serif as though it were an exit on an autobahn. Meanwhile most of the village shops closed and vans stopped calling with the groceries. Steam locomotives no longer thundered up the gradient. The Davidsons went quiet and then dispersed. My father gave up reading newspaper stories which told of ‘fights to save jobs’. Once he threw down the local weekly in disgust: ‘There’s nothing in here but sponsored walks and supermarket bargains.’ He cycled still, taking circuitous routes to avoid the new motorways and coming home to despair at the abundance of cars. Usually on these trips he would revisit his past. The Highlands, fifty miles away, were now beyond him, but even in his seventies he could still manage to reach the Fife hills and the desolate stretch of country which had once been the Fife coalfield. He brought back news to my mother. ‘Do you mind the Lindsay Colliery? It’s all away, there’s nothing there but fields.’ Factories had gone, churches were demolished, railway cuttings filled up with plastic bottles and rusty prams.

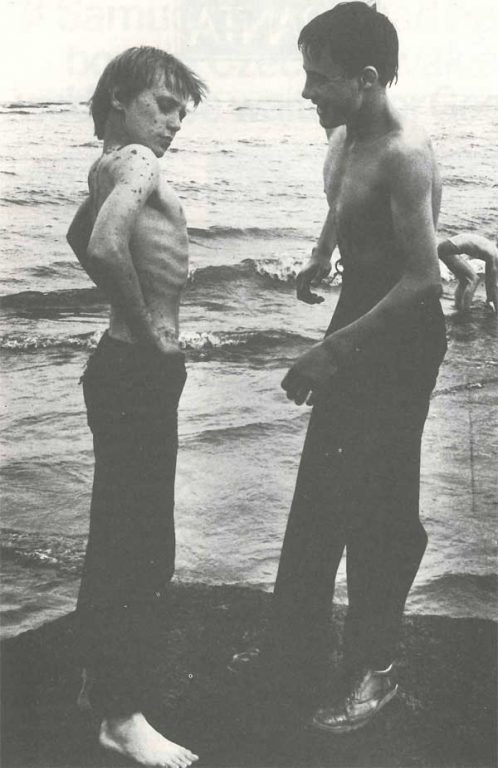

Once around this time we visited an exhibition of old photographs in Dunfermline, his birthplace. One picture showed a street littered with horse dung and small boys standing in a cobbled gutter: the High Street, circa 1909. My father went up close. ‘That’s me on the left there. I remember the day the photographer came.’ We looked at a boy with bare feet and a fringe cropped straight across the forehead. The photograph and the man beside it were difficult to reconcile. Quite suddenly I realized how old my father was. Afterwards he talked about writing his ‘life story’ and we encouraged him; for months of evenings and afternoons he sat in the easy chair with the chessboard and the foolscap on his knee, writing with his fountain pen and smiling.

He became, I suppose, like the people he had always cherished: a character. Like the photograph, he was now of historic interest, and sometimes when I came up from London I expected to find him surrounded by tape recorders and students from the nearest university department of oral history. That did not happen. One day he collapsed into the potato patch he’d been digging. Cancer was diagnosed, eventually, but he never asked for the diagnosis and was never told. For many weeks my mother nursed him as he slipped in and out of pain and consciousness. The pills did not seem to work; he whimpered and cried aloud like an abandoned baby, an awful sound. The doctor decided to change the medication to an old-fashioned liquid cocktail of alcohol, morphine and cocaine. After the first dose he rose bright-eyed from the pillows and saw me, up from London.

‘What’s yon big lazy bugger doing here?’

Those were his last words to me, and my mother worried that I’d been hurt. ‘He’s never spoken about you like that before. I don’t know what came over him.’

We decided that it was bravado induced by alcohol, but I wondered. I remembered all the times I’d failed to help him in the garden; my uselessness with a chisel and saw; and my job, where I never got my hands dirty, or at least not literally. Or perhaps he was simply bored and had decided to liven people up.

The crematorium was a new building, concrete and glass, which had been built (as my father would have been the first to tell his mourners) near the site of one of the first railways in the world. The moorland to the east held mysterious water-filled hollows and old earthworks, traces of an eighteenth-century wagonway which had carried coal from Fife’s first primitive collieries down to sailing barques moored at harbours in the firth. Here my father had played in the summers before 1914, uncovering large square stones with bolt-holes which had once secured the wagonway’s wooden rails. Here also we had gone for walks on Sundays in the 1950s, smashing down thistle-heads and imagining the scene as it must have been when horses were pulling wooden tubs filled with coal. The world’s first industrial revolution sprang from places such as this; it had converted our ancestors from ploughmen into iron moulders, pitmen, bleachers, factory girls, steam mechanics, colonial soldiers and Christian missionaries. Now North Britain’s bold participation in the shaping of the world was over. My father had penetrated the revolution’s secrets when he went to night school and learned the principles of thermodynamics, but as the revolution’s power had failed so had he. His life was bound up with its decline; they almost shared last gasps.

Photograph © Markéta Luscačova