Nobody ever lives their lives all the way up except bull-fighters.

– Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

On 26 April 1976, after suffering a stroke that robbed him of the ability to walk and speak, the matador Sidney Franklin died in a nursing home in Manhattan, roughly thirteen miles from his native Brooklyn. Fifteen years earlier, on 2 July 1961, Ernest Hemingway donned his ‘emperor’s robe’ and shot himself in the head with a double-barreled shotgun. As young men, the two had split bottles of brandy in Spain, had traveled through the countryside together (a remarked-upon odd couple, one clean and effete and the other greasy and unshaven), had watched bombs explode in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. The New Yorker journalist Lillian Ross had said theirs was a friendship between a great man and a lesser one. I am the grand-niece of the lesser one.

*

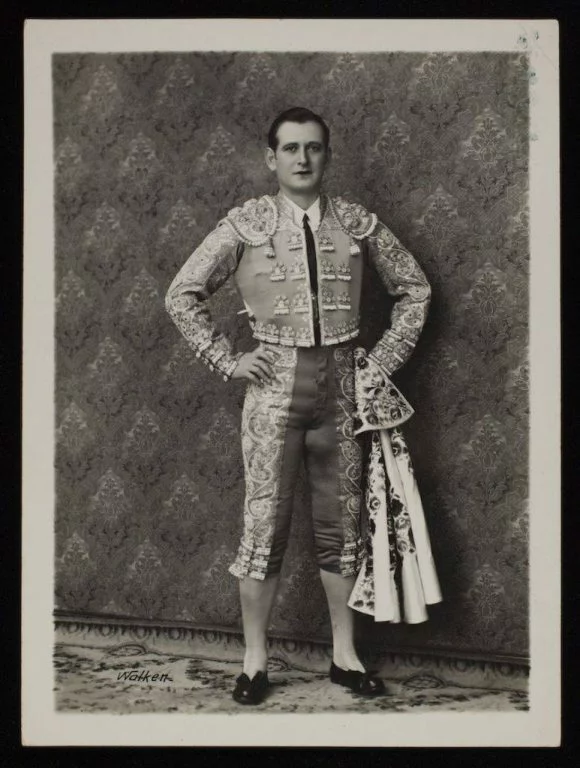

Sidney Franklin was light on his feet and red-haired and slim. He was the son of Russian Jews Abram and Lubba Frumkin – Abram, a policeman who was keen to prove his masculinity to his Irish coworkers, simmered with a fierce disdain for his son, who was grandiose and creative and uninterested in becoming an accountant or teacher like the rest of his nine siblings. Sidney wasn’t athletic and he wasn’t popular. After school, he acted in plays as a part of the New York Globe’s Bedtime Stories Club, and changed his name to Franklin so his father wouldn’t find out. He later abandoned acting, which he called his ‘first love’, determining it to be ‘too feministic’. In his late adolescence, he was sometimes seen in Prospect Park, a place where gay men cruised – family members claim that Abram, who was part of a patrol that maliciously beat these men every Saturday night, saw Sidney there and beat him along with the rest. The family called Sidney fageleh, a Yiddish word meaning ‘queer’ or ‘fag’, though never to his face. In 1922, when he was nineteen, he and a friend spent a weekend in New Jersey’s Asbury Park, a resort town known for its numerous queer bars. Sidney didn’t call his parents to warn them he’d be gone. When he returned home, Abram knocked him unconscious: he didn’t wake up until the next day. Lubba, worried Abram was going to kill him, gave Sidney some of her pushka money – the small sum her husband afforded her every month to run the house. Sidney went as far as the money could take him. This was how he found his way to Mexico City.

In Mexico City, Sidney worked as a silk screen artist. He was talented enough that he was soon being commissioned for theater and soft drink posters and streetcar cards. While Sidney worked, the Mexican bullfighter Rodolfo Gaona was stunning crowds with his capework. In Spain, Miguel Primo de Rivera assumed power in a military coup, paving the way for the formation of a liberal, anti-monarchist republic. In New York, reporters at the Brooklyn Eagle were still licking their wounds over having lost the battle to keep Brooklyn from becoming a borough. The world was turning. Sidney, tall and fastidious and long-nosed, his booming voice instantly betraying his Yanqui awkwardness, wanted to be everything to that world. He was already everything to Sidney Franklin. Even then he had the self-confidence that would lead him to tell Lillian Ross 27 years later: ‘I am the sun, moon, and stars to myself.’

‘Sidney in the Stars’, by Jett Allen

I have come to learn that there is something about having Frumkin blood that makes me want to be the sun, moon, and stars to myself as well. When I was six, I sat on the kitchen counter peeling an orange, wondering when my parents would finally get famous, because didn’t everyone want to be famous? I let people tell me that I would be great from my first week in the gifted and talented program in junior high. In college, I wrote a play and gave it to two friends to direct and then attended every rehearsal, interjecting whenever I disagreed with their methods. (‘This was never ours to direct. This was always a Rebekah Frumkin Production,’ said one of them, rolling her eyes.) In grad school, I fanned my ego with the praise of my professors. I published a novel and was furious when it didn’t make me instantly famous – I wrote emails about my ‘catastrophic failure’ to my thesis advisor, grew miserable when he stopped responding and then refused to write any fiction for a year. There are a familiar set of explanations for this behavior that run along the lines of ‘white middle class entitlement’ or ‘only child narcissism’ or ‘privileged self-obsession’, but none of them quite touch my thirsting, Frumkinian need to be big. Striving to be special or the best or famous are all ways of fighting a yawning murkiness at the back of my mind, a drumbeat of doubt, a staring-into-the-void. Being big means being more important than my messy little human form, than the tedious activities of my daily life, than dully complying with the orders of an irritating boss. Being big means doing something that makes me more than a warm body wandering the earth until death. I will be erased if I don’t become big. I will vanish limb by limb. Eventually there will be no evidence left that I existed at all.

Maybe the murkiness is epigenetic – some ancestors survived a pogrom and subsequently lived in a state of anxious dread, convinced they’d be wiped out at any second – or maybe it’s just chemical, but it found me. And the belief that the murkiness – the badness – can be outrun with bigness is hardly unique to me. I recognize that judging myself big is Napoleonic, so I need some external arbitration, a voting quorum, the larger the better. Sidney was a closeted gay man, a theatrical misfit, the enemy of his brutish father. Could the same murkiness that swarms the back of my mind have swarmed his as he walked the Zócalo?

What made Sidney, a charter member of Aunt Jean’s Humane Club, agree to watch his first bullfight? It wasn’t the capework or the artistry, not the bloody valor of the sport, but a group of Mexican ‘young bloods’ he drank with at the Fenix Café, who declared that Americans were too scared to fight bulls. In a matter of weeks, Sidney had decided to fight a bull for the first time. ‘They razzed me,’ he said, ‘but I said there was nothing to it, that Man was superior to Animal.’ I’m sure Sidney didn’t actually believe this, as he describes the psychology of bulls in thoughtful detail both to Ross and in his autobiography Bullfighter from Brooklyn, claiming to know more about them than he knows about humans. I’m sure he wasn’t taking some principled stance about American bravery, either: over the course of his life, Sidney would bear no particular allegiance to any place but Spain, any culture but Spanish culture – he could really have taken America or left it. What had actually happened was Sidney had found his quorum. He had found his chance to become big.

*

In Sidney’s era, the standard-bearer for Spanish bullfighting was a man named Manuel ‘Manolete’ Rodriguez. Manolete had a long, dour face and a reed-thin body that fit well into a traje de luces (suit of lights), the elaborately embroidered uniform worn by matadors. He was a national hero, described in a US newsreel as ‘truly the champion . . . to each Spanish-speaking child just what Joe DiMaggio is to our American kids.’ In August of 1947, Manolete was fatally gored by a dying bull named Islero in the small city of Linares. Fellow matadors and bullfighting aficionados wore black ties and arm bands for years in honor of him. Children and old women hocked posters of him that read Yo ví a Manolete (‘I saw Manolete’).

Manolete is often described as a ‘serious’ bullfighter – no bounciness, only gravitas. In footage of his bullfights, he is dangerously confident, a flat-footed ballerina willing to demonstrate his bravery by turning his back on an angry bull. The movement that we most closely associate with bullfighting, when the matador holds his cape out and then slowly swings it away from the charging bull, is called a verónica. Manolete’s verónicas are perfectly timed and deftly executed. He seems to know each bull well enough that riling them and killing them appear routine to him – during some verónicas, he looks bored. Said the U.S. newsreel: ‘His supreme confidence in himself seemed almost to reach a point of arrogance.’ Although Sidney debuted almost a decade earlier, he would never achieve Manolete’s immortality. Sidney would attend numerous Manolete bullfights, would crowd Manolete’s hotel room along with scores of fans, would boast on a number of occasions that he himself measured up to the great matador. But Sidney’s quorum felt differently. He had the bravery and technical skill, the aficionados agreed, but he was no artist. No Manolete.

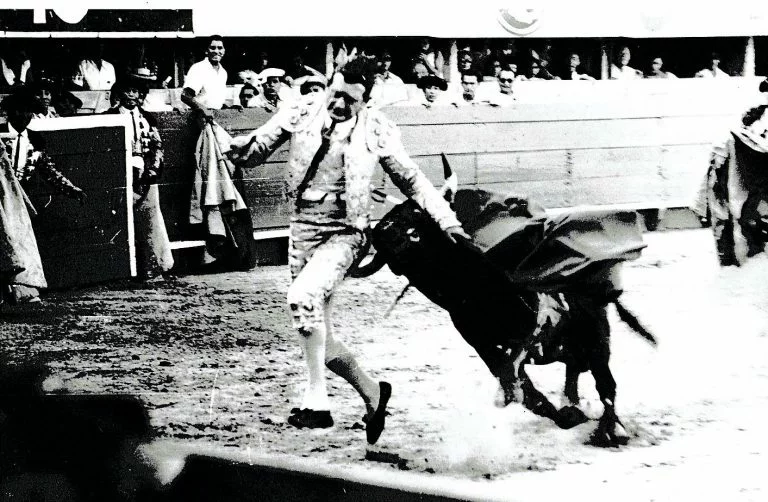

After the ‘razzing’ he received in Mexico, Sidney decided he needed to become the best bullfighter in the history of the sport – and to do that he needed mentorship. He wrote to the most famous matador in Mexico, Rodolfo Gaona, asking to study with him. Incredibly, Gaona agreed, and Sidney traveled to his ranch to study verónicas. His hope was to learn the gaonera, a signature move of Gaona’s in which the matador holds the cape behind him and allows the bull to charge through one side – much more challenging than a verónica. To Sidney’s dismay, Gaona wouldn’t let him progress immediately beyond the simplest moves. ‘He insisted that before attempting anything more advanced I had to learn the fundamental movement of the verónica so well that I would do it in my sleep without thought or effort,’ he wrote in Bullfighter from Brooklyn. When Gaona left to tour, Sidney was invited to an impresario’s hacienda for a three-day fiesta, unaware that he’d be the main attraction. There, before hundreds of guests, Sidney executed his first public verónica. ‘It didn’t matter that my form was terrible. I didn’t have the time, then, nor the experience to think of the details. The fact was that I had actually done it!’

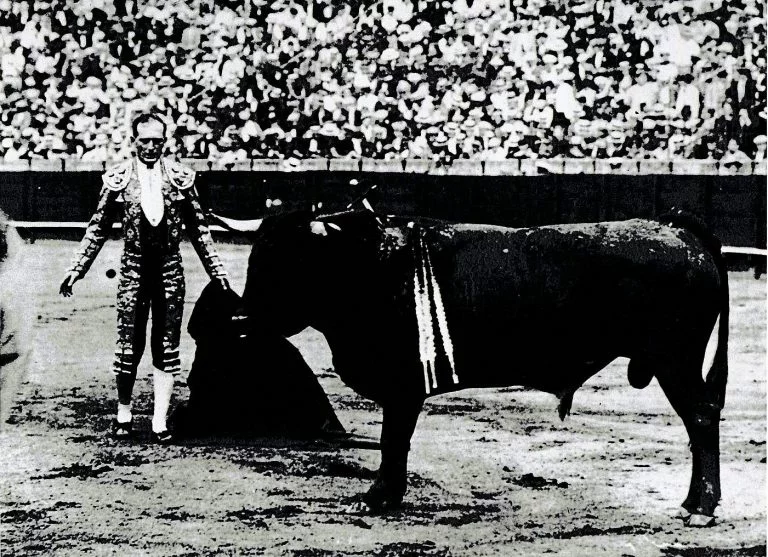

On 19 September 1923, Sidney made his debut in the Chapultepec plaza de toros in Mexico City. Up until that point he had worked only with the cape, and was totally unfamiliar with the instruments of the bullfight’s final act: the muleta, a wooden stick attached to a red cape smaller than the ones Sidney was accustomed to using, and the sword, which is concealed behind the muleta. Sidney would be expected to demonstrate his control over the bull with the muleta before plunging the sword between the bull’s shoulders, piercing the animal’s heart and killing it instantly. If he didn’t kill the bull, he was told, the crowd would do worse things to him than he could do to any bull. Sidney wrote of an incredible – and unlikely – ringside exchange with a member of his entourage, Augustín, who gave him a crash course in bull-killing right before the final act of the fight:

‘Now sight the blade and put it in that little spot where the neck and shoulder blade meet.’

‘But how do I get past the horns?’ I said. I had barely finished with the question with my head turned toward him when Augustín gave me a push. He did it so unexpectedly that I closed my eyes and expected the worst. But, strange as it seems, nothing happened. The bull had gone past me and I was left standing there with just the muleta in my left hand. But where was the sword? I looked around quickly but couldn’t find it.

The sword was in the bull, ‘right up to the hilt’. Sidney, struck by this ‘ludicrous’ turn of events, barely gave himself a moment to consider his accomplishment. Instead he ran to pose next to the vanquished bull, smiling for a horde of photographers and their popping flashbulbs. The crowd of spectators mobbed him, lifted him on their shoulders and carried him the ten miles back to the hacienda. His traje was torn apart by fans greedy for a piece of him. ‘Bullfighters were idolized in a manner I never had seen before,’ Sidney wrote. ‘It was probably at that moment that I knew I would become a bullfighter.’

As a Frumkin, I’m tempted to believe that Sidney wanted bigness not at the cost of death, but at the exclusion of it. Of course Manolete would die by goring – he was practically born in the bullring, after all – and Sidney would not. Sidney was above death, bored of the pomp and seriousness of it. What excited him most was fame, and fame comes in life. Sidney lived and lived and kept on living, shrugging off the injuries he sustained in the ring that could have killed him, shrugging off the truth when he told stories about his life. My second cousin Doris Markowitz, who knew Sidney personally, said that at least half of Sidney’s autobiography, is falsified, especially mentions of girlfriends. (Sidney describes an Elvira, ‘a lovely girl . . . two years older than I,’ who tried to keep him from bullfighting, and whom he summarily left in devotion to his higher calling. The whole relationship lasts about four paragraphs.) All Sidney left on record was his cheerful and sometimes delusional pursuit of bigness, no murkiness. This fact seemed to have piqued Ross and to a lesser extent Bart Paul, the literary critic, short story writer, and horseman whose Double-Edged Sword is the only existing biography of Sidney. In their accounts Sidney reads as more bluster than hero, a quasi-pathetic figure despite – or possibly because of – his moment of fame.

After six years of touring successfully in Mexico, Sidney fought his way to the central stage of the bullfighting world: the Plaza de Toros de la Real Maestranza in Seville. On 9 June 1929, Sidney would acquit himself expertly in the ring, earning praise from Spanish aficionados and major newspapers. Again, adoring fans would flood from their stadium seats to lift Sidney up on their shoulders. Again, they would tear his traje apart, but these would be Spanish hands tearing, the hands of people who considered their arenas too good for Mexican toreros. Sidney would be carried back to his pension and strangers would crowd him – they would even join him in the shower. ‘I enjoyed and savored what I had done with an intensity almost sexually sensual,’ Sidney wrote, and later: ‘All the sexes seem to throw themselves at you.’ The Brooklyn Eagle, which had been covering Sidney’s story in lavish terms since his debut in Mexico, would publish headlines such as ‘Brooklyn Bullfighter Wins Great Ovation in Brilliant Spanish Debut’ and ‘Ten Thousand in Seville Arena Cheer Him as He Dispatches Bovine Foe with Single Stroke.’

Sidney was more than a novelty, a weird American who’d decided to try his hand at a foreign sport: he was a bullfighter in his own right, el único matador, and to his extreme satisfaction more than a little Spanish. He fashioned himself as a sort of cultural ambassador to Spain, singularly capable of introducing bullfighting to his American countrymen. ‘I shall not return to my hometown, Brooklyn, until I have gained fame throughout Spain,’ he told the Eagle. ‘I am sure that as soon as Americans are able to understand the beauty of this art, they will take to it, the same as they have taken to other sports.’ He joined an elite group of Spanish bullfighters whose company he continued to keep for decades. Fifteen years after his debut, he and a fellow American bullfighter would be sharing a bottle of Scotch with Manolete.

‘Popularity is a wonderful thing. It’s better than food,’ Sidney wrote. ‘But it can be terrifying when it gets out of hand.’ Sidney couldn’t walk down the streets of Seville without being recognized and mobbed. He might have been overwhelmed, but that came with the territory. What mattered most – what he spent nearly his entire autobiography emphasizing – was that he was big, and that was better than food. Bigness was, to his mind, what any sane person should want from life. And bigness was what brought him to Hemingway.

*

Sidney was a king in the Madrid of 1929. A Joycean-level genius for languages, Sidney spoke fluent Castilian, Andalusian and cálo, the language of the Spanish and Portuguese Romani. Charmingly, he spoke these languages with his New York accent: in a rare film reel, qué tal becomes kayy tawwl. He was rich, commanding high fees for a novillero – a novice bullfighter who has not yet taken his alternativa, a bullfight-cum-graduation-ceremony in which the young bullfighter is presented to spectators by a mentor (or ‘patron’) as a mature matador de toros at the end of his fight – and he had a personal chef named Mercedés and well-appointed living quarters. Most importantly, he was famous, mobbed in the street and always traveling with several friends, aficionados, and fellow bullfighters. He would have been sitting with twelve such hangers-on at the Café Gran Via on the day in late summer 1929 when a disheveled Hemingway wandered up to his table.

‘By his appearance, this fellow looked as though he needed a handout,’ Sidney wrote. Hemingway hadn’t shaved and needed a haircut. His suit ‘had forgotten what a tailor’s iron felt like’. He wore battered bedroom slippers. He asked if Sidney was Sidney Franklin, the famous matador. Guy Hickock, a Paris correspondent for the Brooklyn Eagle, was supposed to have written Sidney with an introduction.

‘I’m the fellow he mentioned,’ Hemingway said. ‘I’m Ernest Hemingway.’

Hemingway was invited to sit, and Sidney told him to order whatever he wanted. Hemingway declined, saying that ‘wouldn’t be right’, and ordered a bottle of Pernod, insisting on paying for it himself. He explained that Pernod was like absinthe, which the healthy, athletic Sidney felt was ‘shrouded in a certain mystery . . . like cocaine, heroin, or opium.’ He definitely wanted to see what this absinthe tasted like.

So the friendship began: they drank together and watched bullfights together. Sidney introduced Hemingway to his matador friends, at least those Hemingway didn’t know already. They stayed up all night talking and drinking like teenaged girls at a suburban sleepover. By then, Hemingway had published The Sun Also Rises, the story of a lost generation of young expatriates discovering the world of bullfighting in Pamplona. The book had received mixed reviews but had nevertheless put him on the map. He was months away from publishing A Farewell to Arms, which would launch him into the realm of literary stardom. Hemingway, like Sidney, had a chip on his shoulder about being an American enthusiast for a centuries-old Spanish tradition. ‘Somehow it was taken for granted that an American could not have afición,’ Jakes Barnes says in The Sun Also Rises:

[The American] might simulate or confuse it with excitement, but he could not really have it. When they saw that I had afición, and there was no password, no set questions that could bring it out, rather it was a sort of oral spiritual examination with the questions always a little on the defensive and never apparent, there was this same embarrassed putting the hand on the shoulder, or a ‘Buen hombre.’ But nearly always there was the actual touching. It seemed as though they wanted to touch you to make it certain.

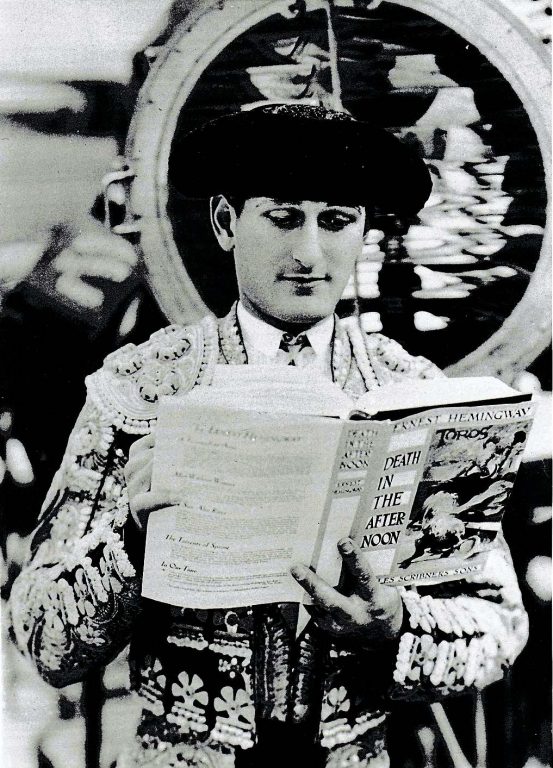

Hemingway took up the mantle of defending Sidney against Spanish claims that he was nothing more than an American novelty. In a few pages of Death in the Afternoon titled ‘A Short Estimate of the American, Sidney Franklin, as a Matador,’ Hemingway writes that ‘actual Spaniards’ said of Sidney’s bullfighting abilities that he was ‘very brave but very awkward and did not know what it was all about’. Hemingway’s response: ‘Franklin is brave with a cold, serene, and intelligent valor but instead of being awkward he is one of the most skillful, graceful, and slow manipulators of a cape fighting to-day.’ But a true aficionado like Hemingway would almost certainly have noticed the difference between Sidney and the Spanish greats. Watching old footage of Sidney fighting is a very different experience from watching Manolete. While both seem to understand well the interiority of bulls and be very capable in dispatching of them, Sidney is exuberant where Manolete is somber. Sidney does not restrict his movements nearly so much as Manolete does: the former’s feet describe wide arcs, running and even galloping where the latter side-steps. Manolete seems born to bullfight whereas Sidney seems born to do a lot of things, bullfighting among them. Sidney is a showman and Manolete is a craftsman.

Sidney and Hemingway adored each other, though Sidney was ignorant of Hemingway’s world of letters. He read only The Saturday Evening Post, which he read cover-to-cover over a period of three days, spending the following four waiting for the next issue and reading nothing else but wine menus and the occasional Spanish newspaper. When asked several years later if he’d read For Whom the Bell Tolls, Hemingway’s novel about an anti-fascist guerrilla named Robert Jordan fighting in the Spanish Civil War, Sidney responded flatly: ‘I don’t have to read it. I am Robert Jordan.’ His friend was an outspoken antifascist, but Sidney was politically indifferent. A 2019 Spanish newscast described Sidney as a ‘homosexual who was a victim of Francoist repression.’ I’m sure Sidney would have balked at this: he’d have denied his homosexuality, of course, but he’d have also denied that he was oppressed by Francoist conservatism. How could a wealthy and beloved bullfighter possibly be oppressed?

Hemingway noticed Sidney’s aversion to death. He killed his bulls too easily, without drama, failing to ‘give the importance to killing that it merits . . . because he ignores the danger.’ In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway wrote: ‘Bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death and in which the degree of brilliance in the performance is left to the fighter’s honor.’ Hemingway, who admitted that he killed wild game so he wouldn’t kill himself, and once used his head as a battering ram until his ear leaked cerebrospinal fluid, seemed more fascinated by death than Sidney was. Instead of dwelling on his honor-bound duty to face his mortality, Sidney spent thousands of dollars on his trajes, posing for paintings in gold and pink embroidery and turning verónicas with capes so beautiful one woman spectator commented that they’d make lovely evening wraps. (Sidney was incensed: ‘You don’t pay six hundred dollars for an evening wrap!’ he shot back.)

Hemingway advised him to make the killing look harder, but Sidney did not seem to take the advice. (Hemingway also wrote that Sidney had ‘no grace because he had a terrific behind,’ and tried to get him to do ‘special exercises to reduce his behind,’ which exercises Sidney didn’t seem to have taken to either.) It’s tempting to think that had Sidney taken Hemingway’s advice, he could have been a Manolete, or even a Belmonte or an Ordóñez, that he could have converted to Spanish life and culture the way a particularly disciplined hopeful can convert to Judaism, the religion Sidney had abandoned for a glancing and cheerful acquaintance with Spanish Catholicism. But he was never destined to be a Spanish bullfighter – not because he was an American, but because he cared about bigness more than death.

During Sidney’s brief moment at the top, Hemingway spent a good deal of time in Sidney’s room in Madrid listening to him talk. Sidney was a storyteller – everyone in my family who had the pleasure of making his acquaintance confirms this – and though he was an artless writer he was a fantastic speaker just by virtue of his knack for accumulating detail. In a passage in Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway writes in the same breathless, distractible staccato of Sidney’s speech, describing in one paragraph a string of days in Sidney’s busy apartment, Sidney’s many visitors, his tidiness, and his cavalier disregard for his own health:

And up in Sidney’s rooms, the ones coming to ask for work when he was fighting, the ones to borrow money, the ones for an old shirt, a suit of clothes; all bullfighters, all well known somewhere at the hour of eating, all formally polite, all out of luck; the muletas folded and piled; the capes all folded flat; sticks are in the bottom drawer, suits hung in the trunk, cloth covered to protect the gold; my whiskey in an earthen crock; Mercédes, bring the glasses; she says he had a fever all night long and only went out an hour ago. So then he comes in. How do you feel? Great. She says you had a fever. But I feel great now. What do you say, Doctor, why not eat here? She can get something and make a salad. Mercédes oh Mercédes.

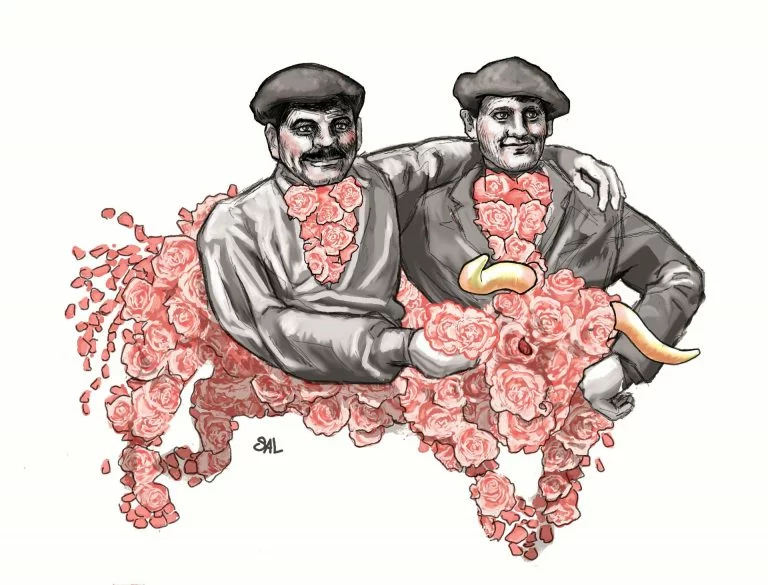

I have a photo of Sidney and Hemingway from their time together in Spain, standing in front of a castle in the countryside and grinning, their arms over each other’s shoulders. In the photo, Hemingway stands with his legs shoulder-width apart and Sidney stands with his left hip cocked. They both wear berets. It was this photo that made me want to read the book that had launched Hemingway’s career shortly after the two met.

When I told writer friends that I was reading A Farewell to Arms, the responses were animated, to say the least. ‘Hemingway, that macho bigot? He’s irrelevant, anyway. Why are you reading him?’ There were exasperated accounts of being forced to read The Old Man and the Sea or ‘Hills Like White Elephants’ in high school, of hating the terse, telegraphic style that has since become a parody of itself. I replied that I was reading Hemingway because I wanted to, and then added that my gay great-uncle had been his friend. ‘Your gay great-uncle?’ came the response. ‘Ernest Hemingway had a gay friend?’

I told myself that reading this book, which contained no mention of Sidney or his profession, would give me an opportunity to honestly appraise Hemingway the writer. It had been nearly a decade since grad school, when I had read (and secretly enjoyed) In Our Time, and much more than a decade since I’d read the usual Hemingway fare assigned in American literature courses. Hemingway the man, the highly cancelable man who cheated on his wives, drank heavily, wrote characters who wanted to beat up ‘superior, simpering’ gay men, hoarded guns, killed wild animals for sport, and threw a tantrum when his wife Pauline shot a lion before he did, had to be irrelevant, at least for the time being. I knew that Farewell to Arms is an enhanced (in the most masculine sense of the word) retelling of Hemingway’s own life. I figured that Hemingway the man would intrude, and that I would have no hope of enjoying my read.

The man didn’t intrude. At least not that much. Hemingway’s lieutenant Frederic Henry falls in love with the nurse Catherine Barkley, who predictably dies in childbirth, but that felt secondary to Henry’s bizarre and quasi-symbiotic relationship with his roommate, the Italian surgeon Rinaldi. Without Rinaldi, Henry would never have met Barkley; without Henry, Rinaldi would have no one to get drunk with or kiss. Rinaldi kisses Henry four times, two of which Henry manages to rebuff. (Hemingway scholar Michael Reynolds writes of one instance that Rinaldi’s advance was a ‘brotherly kiss that Frederic does not accept’ [italics mine].) Henry is often Rinaldi’s ‘baby,’ his ‘poor dear baby,’ as in: ‘Poor dear baby, how do you feel?’ and ‘You are drunk, baby’ and ‘I just tell you, baby, for your own good.’ Of course, ‘baby’ could be a catch-all term of endearment (though it doesn’t directly translate to any of the typical Italian terms, bella, tesoro, cara or amore), but then Rinaldi goes so far as to profess his heartbrokenness when Henry leaves for battle, and he visits Henry when he’s wounded in the hospital. Rinaldi’s affections don’t appear to go unreciprocated:

I took off my tunic and shirt and washed in the cold water in the basin. While I rubbed myself with a towel I looked around the room and out the window and at Rinaldi lying with his eyes closed on the bed. He was good-looking, was my age, and he came from Amalfi. He loved being a surgeon and we were great friends. While I was looking at him he opened his eyes.

Between the Pernod-swilling and the girl-kissing, there is an obvious reverence for the homosocial in Hemingway’s work. Consider his corpus and it’s impossible to ignore how many paragraphs are spent talking about men being with men and admiring one another while doing so. This is not to make some inference of queerness based on Hemingway’s masculine posturing and man-obsession, to lump him in with GOP senators whose vocal homophobia on the senate floor is unmatched by their passion for one another in bathroom stalls. Although Hemingway and Sidney did share a few beds out of convenience, and my cousin Doris told me that there are letters of Hemingway’s at the Kennedy Center which suggest he may have been ‘AC/DC’ (20s slang for bisexual), this is not enough to build a convincing case for queerness. The scholar Mary Dearborn, whose 2017 Hemingway: A Biography is the first comprehensive biography of Hemingway in nearly two decades, told me definitively: ‘It’s really clear that Hemingway was not gay.’

We know that Hemingway kept queer company: there were Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, (at least until his falling out with Stein), and the gay Red Cross officer Jim Gamble, who offered Hemingway a year to focus on his writing as Gamble’s ‘paid companion’. (Hemingway very seriously considered taking Gamble up on his offer. ‘Imagine how the course of American literature would have been different had he done so!’ Mary wrote me.) We know that Hemingway was undeterred by heterosexual propriety from describing the beauty of men: in The Sun Also Rises, the nineteen-year-old bullfighter Pedro Romero’s ‘black hair shone under the electric light’, and Jake Barnes declares him ‘the best-looking boy I have ever seen’. We know, too, that Hemingway had surprising insight into abuse in queer relationships. In Death in the Afternoon, he recounts with a good deal of tenderness the story of two male ‘friends’, one older and moneyed and the other younger and broke, who get into a fight in the middle of the night, presumably over the younger one’s unwillingness to sleep with the older one. ‘Nothing on earth would make him go back in that room. He would kill himself,’ Hemingway quotes the younger friend. For all Hemingway’s bluster, these corners of the world weren’t unknown to him, and he didn’t seem to resist knowing them. ‘I’m 99 per cent sure Hemingway would have known about Franklin’s sexual preference,’ Mary said. Based on The Sun Also Rises alone, it seems more likely that Hemingway would have held Sidney’s Jewishness against him than his queerness.

In March of 1930, Sidney was avidly exchanging letters with Hemingway (who was in Key West celebrating the massive success of A Farewell to Arms) and enjoying the peak of his fame. Then he turned his back on a bull in Madrid and received a devastating goring. The horn pierced Sidney at the tailbone, ripping his sphincter muscle and large intestine, sinking, as he put it, ‘to the ear’. Doctors advised he spend months in bed and sit out the rest of the season. Concerned about losing money, Sidney was back in the ring in five weeks, fighting in incredibly poor physical shape. He spent that winter fighting in Mexico, where he received another horn wound to his calf. Doctors injected him with anti-tetanus and anti-gangrene vaccines that caused his left arm to become discolored and swollen and ruined his 1931 season in Spain. When he tried to return the year after, the Spanish impresarios took their revenge on him: when he was packing stadiums, he’d made them pay top-dollar for his matches – much more than was typically afforded a novillero. Now, the impresarios put off his requests until they’d filled every slot for that season.

Sidney would never again achieve the level of notoriety he’d once had. He would string together minor fights much the same way Hemingway had written articles for the Toronto Star: dutifully, for a paycheck, always nursing ambitions of something bigger. But whereas Hemingway was on the ascent, Sidney rapidly declined – the latter’s profession required perfect health, and he’d lost his. Hemingway to Ross: ‘Before the horn wound, [Sidney] had the real completely. Because of his bad wound he lost the real in bullfighting.’

Sidney tried to become an impresario, one of the promoters who booked fighters at various arenas. He cooked up a scheme to introduce bullfighting to Cuba, even trying to get Hemingway involved. The plan never came to fruition. He fought more small-time fights in Mexico, drudge work, the poorly-maintained rings holding none of the glamor of his major fights in Spain. He expanded his horizons beyond the bullring and became a consultant for the 1932 film The Kid from Spain, in which Eddie Cantor is on the lam in Mexico and poses as a bullfighter to outrun American authorities. Sidney even played himself for a few minutes. One character refers to him as ‘the great American bullfighter’ and offers him a standing ovation before he does anything in the ring. The fight is, of course, bloodless: Sidney gouges the camera, not the bull, with his muleta.

If Sidney was envious of the bullfighters with more illustrious careers than his own, he left no record of it. In fact, there’s a certain generosity in his excitement to watch them fight, and share a few glasses of Fundador with them in their hotel rooms afterwards. He seemed as happy to crowd the pension as he was to be the one whose pension got crowded. At worst, this looks like more grandiosity, more obsession with proximity to fame – I am friends with the greats, therefore I must be great myself – but there’s a kinder interpretation of Sidney’s friendliness. Maybe Sidney just loved people and loved bullfighting and wanted to be at the heady center of it all. Maybe he was just the kind of guy who felt great sharing his homespun theories about the mind-body problem with a ringside psychiatrist in Mexico City. (‘I say the brain directs everything in the body. It’s all a matter of what’s in your mind.’ Said the psychiatrist: ‘You’re something of a psychosomaticist.’) He plied people with stories of his lives in Brooklyn, Mexico, and Spain – Hemingway called him ‘one of the best storytellers I have ever heard.’ Post-goring, Sidney seemed to understand bigness as togetherness. He didn’t need to stay completely in the spotlight. In an early 30s photo out of his traje, he is smartly dressed in a jacket, fedora and Windsor-knotted tie, thick-eyebrowed, half-smiling, clearly very pleased to be photographed but not too pleased: older than he was at the height of his fame and seemingly untroubled by the threat of aging. It is clear looking at this photo that Sidney was an optimist. An opportunist, sure, but an optimist as well.

I wish I had seen this photo when I was beside myself with anger and envy after the publication of my novel. It would take me years to understand what Sidney seemed to know even through the bluster that bored his biographers and friends: there is more to outrunning the badness than just being famous. Ours isn’t a Manichaean world of fame or mediocrity. ‘Bigness’ can mean loving and being loved. And it’s that, not getting mobbed in the street or carried away on shoulders, that’s better than food.

*

Doris Ann Markowitz is 79 and lives with her husband in Boynton Beach, Florida, in a community for people over the age of 55. Before she retired, she taught gifted and talented elementary and high school students. She describes herself as musically and artistically talented. Her home is decorated with her paintings and shadowbox collages. She showed me a collection of dolls she’d made – fabrics, threads and yarns stretched over metal armatures. They were faceless, or else just had eyes or noses or mouths. ‘I never make the full face so I can leave a bit of mystery in the dolls that I create,’ she said.

She’s given interviews about Sidney to the New York Times and an archivist at the American Jewish Historical Society where the letters, photos and other ephemera that survived Sidney’s life are kept. She good-naturedly chastised Bart Paul for spelling the family name ‘Frumpkin’ in the first few chapters of his book. (Paul claims another Frumkin cousin told him the name was spelt with a ‘p’.) The misspelling smarted everyone a bit, I think, because our name has been twisted into ‘pumpkin’ or ‘frumpy’ on three generations of playgrounds.) Doris is the daughter of Helen, Sidney’s younger sister by three years. ‘Uncle Sidney would have loved to be in the limelight, so anything that I could add from my relationship with him, I wanted out there,’ she told me.

Sidney had to return to Brooklyn every six and a half years or he’d lose his American citizenship, and he usually went straight to Helen’s house. Helen was large-framed, went deep-sea fishing with her brothers, and had been a racing canoeist on the men’s team in high school. She loved her father but she also loved Sidney. ‘When they were together, there was nobody in the room except the two of them,’ Doris says. ‘They adored each other.’ Whenever Sidney sent word that he was arriving, Helen undertook some home improvement project – a new set of drapes, maybe, or a rearrangement of furniture in the living room – and Doris did her ‘Uncle Sidney dance.’ When Sidney arrived, it was bearing silver jewelry from Mexico or photographs and postcards from Spain. And he always seemed to show up at the moments he was most needed. He helped Helen convalesce after her gallbladder removal and brought her to the hospital in the middle of a snowstorm when she went into labor with Doris’s sister and Doris’s father was trapped in Jersey City. Despite the distance he’d put between himself and Brooklyn, Sidney slid effortlessly back into family life whenever he was stateside.

Sidney told his stories of bullfighting, carousing with Hemingway, traveling in Spain and Mexico. Doris was desperate for information about the world outside of Brooklyn and drank up every word he said. ‘He opened a new world in my head to all the places he went. When he was around, the world exploded in a very positive way,’ she said. When Doris misbehaved, Helen locked her in a closet under the stairs. Luckily, this was where all of Doris’s painting materials were kept: she would spend her confinements painting frescoes on the walls and hardly notice she was being punished. Sidney was a huge admirer of these frescoes. He painted one himself in his mother’s house, an imitation of a pre-war Japanese painting, with ‘Japanese women and men and bridges and streams and little icons,’ Doris said. ‘It was the most magnificent thing I had ever seen done.’ Sidney taught Doris how to draw perspective and how to mix oil paints. He painted her hands, fingers, face and arms and then looked in the mirror with her to see the blended colors. When she understood his lessons he’d take her in his arms and say ‘I can’t wait to teach you more things, Dory!’ When Helen stumbled in on their messy scenes, Sidney would laugh: ‘Artists get dirty, Helen. That’s what we do.’

To us Frumkins Sidney will always be interstellar. My father recalls getting dinner with him at Idlewild Airport in 1964 when Sidney was stopping over in New York on his way to Mexico. My father was ten years old at the time and had no idea who Hemingway was or who any of the obscure relatives were that Sidney and his father spoke about. My father was dazzled by the famous bullfighter somehow sitting at the same table as him. My grandfather, who at that point looked like a denser, less well-kempt Sidney, had lost his frightening temper and serenely asked Sidney questions about his exploits. ‘I think my father had a sense of pride about Sidney,’ my father told me. ‘ “My older brother, the famous matador. Here’s a Frumkin who did well.” ’

Was he really as great as all that? Perhaps it’s hard to resist embellishing when speaking about as inveterate an embellisher as Sidney. There is such disregard for the truth in his own accounts of his life that any of us can use him as a canvas across which to splash our personal aspirations and fears. Maybe that’s all New Journalism really is. Maybe that’s all I’m doing right now. Living and feeling big is about swallowing the world whole and making it one’s own. If Sidney and Hemingway could do it, why can’t I?

So I will. My great-uncle had the litheness and delicate features of a Semitic twink and cruised in Prospect Park in the 20s; and he was warm and also a blowhard; and he was a goddamn bullfighter in a family of CPAs and teachers and doctors; and he once tried to make paella in his sister’s house and the pressure cooker exploded and chicken wings stuck to the ceiling; and he bequeathed the rights to his book to another cousin who tried to adapt his story into a screenplay starring Robert DeNiro as Sidney, Robert Duvall as Abram and Meryl Streep as Lubba; and through obsessive attention to detail, he made a lame Eddie Cantor vehicle into the most accurate portrayal of bullfighting in an American film; and when he wasn’t in his traje he wore a fedora and carried a slim silver cigarette case; and I want to wear his fedora and carry his slim silver cigarette case; and I would not object to being a gay Jewish bullfighter from Brooklyn myself; and I’m proud to be related to a liar as creative as Sidney, because I make a living lying creatively; and I recently had a dream where I was trying to perform a verónica and the cape was so heavy with embroidery that I couldn’t get it right until the fourth or fifth try; and I think sometimes when I wake up late after staying up late that I am waiting for something big to happen in my life, and I stare at the ceiling and breathe as evenly as I can and tell myself that my life will not be an adventure until I get out of bed and do something about it.

*

By 1936, Sidney was not fighting bulls with the regularity he had fought them before his injuries. He was instead traveling between Mexico and Spain, staying at the homes of ranchers and bullfighters and aficionados he still knew from his heyday, and spending a greater amount of time with his family in Brooklyn than he had before. He tried a second time to introduce bullfighting to Cuba and failed again, and it was in the fog of disappointment that he met Hemingway in Havana. Hemingway had a proposition for Sidney: he had just signed a contract to cover the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance, and he wanted Sidney to come with him. Otherwise unoccupied, Sidney agreed to what he was sure would be a big, Hemingwayan adventure.

‘Hemingway and Sidney’, by Sarah Langenbacher

Their trip to Spain was a strange one. Hemingway, now famous and equipped with a foreign correspondent’s visa, travelled in a private car from Paris to Madrid, where he met his mistress Martha Gellhorn, a foreign correspondent for Collier’s. Sidney was forced to negotiate a backdoor crossing of the Spanish border with the aid of a group of antifascist loyalists in Paris. He rode a train to Toulouse and then a series of scrap-metal buses to the border. He crossed the border chin-deep in an icy river with a diverse group of men who’d come to fight for the loyalists. On his head he carried a much-needed surgical kit to be delivered to a doctor in Valencia. ‘When Sidney promised to do something, he did it,’ another man in Sidney’s party told Ross. ‘He didn’t understand fear.’ Sidney estimated the surgical kit cost seventy-two thousand Francs and saved ‘God knows how many lives.’ This was perhaps a moment in which his self-comparison to Robert Jordan was merited, though Sidney, unlike Jordan, was a political naïf performing unpaid labor for his celebrated friend. (On meeting Hemingway’s Paris friends before illegally crossing the Spanish border: ‘Some of the crowd were violently pro-Madrid and some were just as violent in their support of Franco. They all thought it was very strange that I didn’t know even then which side Ernest intended going in on.’)

When Sidney finally landed in Valencia, he obeyed Hemingway’s orders to stock up on food and packed a small Citröen with ‘six large Spanish hams, ten kilos of fine coffee, twelve kilos of caramels, four kilos of real butter, two five-gallon cans of lard, a hundred cans of a kilo each of varied marmalades and jellies, and a one-hundred-kilo basket of oranges, grapefruits, and lemons.’ (Alcohol wasn’t on the list – Hemingway had already arranged for a hefty shipment of hard liquor.) Then Sidney picked up Martha Gellhorn, who was staying in Valencia’s Hotel Victoria, and a reporter for the Federated Press named Ted Allan. Gellhorn and Allan flirted the entire way to Madrid and behaved like tourists, insisting on constant stops to stretch or eat ‘ersatz’ Spanish food in little broken-down cafes. ‘I had to threaten to leave them behind before I could get them back in the car,’ Sidney wrote bitterly.

Sidney’s experience as Hemingway’s factotum during the Spanish Civil War merits only a chapter in Bullfighter from Brooklyn, the final one. For all the wartime chaos, this chapter is the least chest-thumping of them all: Sidney is frequently bewildered by the violence around him. After checking in to Hotel Florida, the foreign press hub of Madrid, he hears a shell explode at the edge of the sidewalk. He runs to his window to see a hole ‘with a man . . . lying face down on the farther rim of that hole.’ Sidney alleged that he rushed out to the site of the explosion and pulled the man away from the hole only to find that the man’s head had been cleanly severed from his neck. ‘I stood there frozen by the horror of what I saw. Suddenly people seemed to be shouting from all directions at once, even though I couldn’t see anyone . . . Sick to my stomach, I walked slowly back to the hotel.’

Sidney writes that the correspondents sat in a building removed from the front, receiving daily bulletins of the war prepared by the communist Junta de Defensa de Madrid. The correspondents would decide by coin toss who would get to write about which paragraph and would then use their imaginations to elaborate on what they’d read. Sometimes famous correspondents or authors would make quick trips out to the front and back and then elaborate on stories they’d written in Paris according to their own prejudices, using the Madrid dateline for legitimacy. ‘It made me hate their guts,’ Sidney fumed in Brooklyn parlance. A rare instance of Sidney bristling at lies. Sidney’s experience in Spain that year would be different from those of his disaster-tourist companions. Hemingway, who fashioned himself a rugged American guerrilla during the war, traveled everywhere by private car – often piloted by Sidney himself – and tidy, politically ignorant Sidney did the fixing, the cloak-and-dagger negotiations in the back alleys of Paris, the icy river crossing with the actual guerrillas.

Sidney and Hemingway would travel to different parts of the front – Sidney knew where it was safest to travel – and then return and compare notes, Hemingway ‘combining his stuff with mine’. Then Hemingway would write his report in longhand, Sidney would type it, Hemingway would give it his final approval, and Sidney would take it to the censors and send it off on the cable. Along with John Dos Passos and leftist documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens, Hemingway planned to make a film about the loyalist experience of the Spanish Civil War called The Spanish Earth. No one involved in the film knew the geography like Sidney did, so he acted as chauffeur, driving Dos Passos, Ivens, Hemingway and Gellhorn to countryside hilltops from which they would be able to watch the fighting without risking any danger. Hemingway often took these occasions to act the military expert, pretending that his two months driving ambulances during World War I had afforded him real combat experience: his commentary on shellfire and ballistics and tactical maneuvering was near-constant. When Hemingway and Gellhorn left Madrid to spend ten days deep in the Sierra de Guadarrama, Joris Ivens sent Sidney and cameraman John Ferno do the village of Fuentidueña to film the final two days of The Spanish Earth. Sidney performed his duties as site scout, gaffer and assistant director without complaint.

The best passage in Bullfighter from Brooklyn comes just a few pages from the end. It’s a description of the senselessness of war written by what appears to have been the only American in Spain at the time who hadn’t convinced himself he was a hero of the conflict:

Another thing which showed me the futility of the whole thing was what I saw in the front lines. Soldiers of both sides spent the sundown hours singing their [Romani] ditties back and forth. One would sing a stanza and the other side would answer. Somewhere in their song they’d inject the fact that they had an abundance of things the others didn’t have. When they hit on something they could use for a needy exchange, they would call a halt to hostilities. One soldier with a white flag would leave each side simultaneously. The lines were only a hundred and fifty feet apart. They would meet halfway, exchange coffee and cigarettes, and return to their positions. Then they would fire a few token shots and that was that.

Instead of extolling the nobility of carnage, Sidney was beginning to see it for what it was: the sacrifice of lives for ideological pageantry. Even after a lifetime of bombast, he wasn’t prepared for the brutal reality of politics.

*

In 1945, Sidney quietly took his alternativa in Madrid. He was 42 and thicker in the stomach and chest than he had been in his 20s. In a photo taken that year in his traje, he grimaces at the camera as if he’s either dyspeptic or suspicious of the photographer. He was bald with a thinning monk’s ring of red hair. He wore toupees for formal occasions; he had to clip a fake pigtail to the back of his head for the fight. It had taken him 22 years to finally take his alternativa – Manolete had debuted later than Sidney, in 1931, and taken his alternativa in 1939. Writes Paul: ‘As important as his alternativa was to Sidney, the world of official bullfighting in Spain took little notice.’ Sidney was finally a matador de toros. Never mind that he’d been using custom letterhead for several years with the words Sidney Franklin, Matador de Toros printed at the top.

These were decades of steadily waning importance. Sidney trained young protégés at a short-lived bullfighting school and eventually took to training them one-on-one and referring to them affectionately as his ‘nephews’. He wrote Bullfighter from Brooklyn, which sold poorly, and adamantly promoted it to everyone he met. He tried to smuggle a car into the United States from Francoist Spain, got caught, and did a short stint in prison. He set up a bloodless corrida, much like the one in The Kid from Spain, at the 1939 New York World’s Fair: the corrida fell apart and lost everyone money.

This is the era of Sidney’s life where the rumors spread about him haunt me. He said that the one upside of the World’s Fair debacle was gaining the friendship of ‘a sixteen-year-old Brooklyn neighbor’ named Julian Faria, whom he decided to teach to become a matador. Another ‘nephew’, this one twenty years his junior. Was Sidney – boisterous, crazy, colorful Sidney – grooming these boys? Or am I just made uneasy by Sidney’s boorish pursuit of success and influence long past his prime? Patrick Cunningham, a former student at Sidney’s bullfighting school, wrote a novelization of his experience called A River of Lions in which the Sidney character, a certain ‘Torero from Texas,’ is portrayed as a ‘greasy pederast’ who invites a young boy into his bed and interrupts a formal dinner hosted by well-known aficionados to hand out copies of his underperforming book. An old friend of Sidney’s told Hemingway biographer Jeffrey Meyers that Sidney was ‘a homosexual and a child molester’.

It seems obvious to me, biased as I am – as we all are – towards youth and vibrancy, that Sidney in his younger years was not a villain. But what if he really was, and the cracks and fissures in his persona only began to show as he aged, as he fumbled for relevance and dignity? What if I am related to, and now writing an essay about, someone who wrought real damage in other people’s lives? Or what if I am ashamed of the broken-down Sidney, the embarrassing Sidney, and that is why I am tempted to believe these accusations – accusations that could very well have been motivated by homophobia?

There may be awfulness lurking beneath Sidney’s gold-embroidered surface – he could have intimidated and humiliated people smaller and less powerful than himself, things plenty of celebrated figures have been known to do, and things which have frequently gone ignored so as not to ruin the celebration – but we have only conjecture from a few sources and no testimony. Sidney is not Hemingway: he is a minor historical figure, a footnote, his life borne witness to by a select group within the fairly insular world of bullfighting, the ink spilled over him a fraction of the ink spilled over Hemingway, the film developed of him miles shorter than that of his famous friend. What exists for someone like me, a Frumkin and a queer person who wants to live a big life, are squirreled-away photos of brilliant bullfights, accomplished silkscreen prints, and a remarkable audio recording of Sidney, Lubba and one of Sidney’s protégés happily singing showtunes in Lubba’s kitchen. What exists is a myth-made man.

*

At the end of his life, Hemingway the writer could no longer write. ‘The words aren’t coming,’ he tearfully told his fourth wife Mary. He was a prisoner to sinister delusions that he was being followed by government moles, and attempted suicide a number of times before he succeeded on that July morning in 1961.

At the end of his life, Sidney the bullfighter and storyteller could no longer stand or speak. He wore a brace on his useless right arm and passed time in his dusty room with a single bed, or else in a communal room with other disabled seniors watching television. Unlike Hemingway, who had enjoyed adulation, comfort and a prominent role in the American cultural mythos, Sidney wanted to keep living. When an old friend came to visit him in the nursing home, Sidney pantomimed a verónica and pointed to a calendar next to his bed, indicating that he wanted to see the bullfights the next summer in Seville.

Hemingway’s actions are tragic beyond a doubt, but they must have made sense in his head (I guess this because I have, in low moments, felt myself in a similar bind): he had a reason for being, and that was writing, and now that writing had been taken away, he had no reason for being. A dyed-in-the-wool writer, he lived his life out on the page just as Manolete lived his out in the bullring. But Sidney wasn’t a dyed-in-the-wool anything. He loved bullfighting and was good at it, but he loved many other things as well, and it was this inability to weld himself to a single reason for being that preserved his life through decades of irrelevance and tragedy. Even when Sidney was an annoying friend and a self-aggrandizing has-been, it could never be said of him that he wasn’t an optimist. The funks I get into – the ones in which I think dangerous thoughts and berate myself for not being big in my own right – seem not to have been inherited from Sidney.

What I did inherit from Sidney was queerness. I abandoned cis femininity a long time ago – gave up on long hair, dresses and the dream of pregnancy – but didn’t stray too far into the realm of masculinity, either. I am waist-deep in gender ambiguity, just enough to feel the warmth of being not-exactly-she but not so much that I’ve asked more than a few people to call me by gender-neutral pronouns. Pronouns don’t particularly matter to me, anyway. I have spent a lifetime of Halloweens in drag – Charlie Chaplin (whom Sidney once taught how to perform a verónica), Indiana Jones, David Lynch – and am most at home there, not when I’m simply a girl or a boy but when I’m one pretending to be the other, when I can call upon either at a moment’s notice. I want to be a convincing girl-boy, wearing suits (not too formal, no patterns, no bowties), an occasional tie, sunglasses (round and opaque, a style from the 20s) and button-ups.

Hemingway had a transgender daughter named Gloria. She, like Hemingway, was bipolar and an alcoholic. There is little written about her that doesn’t misgender her or refer to her by her deadname. She attended the University of Miami Medical School and practiced as a doctor during the 70s and 80s, but lost her license because she was ‘wrestling with alcohol abuse and emotional problems’, according to her New York Times obituary. In 1976, she published Papa: A Personal Memoir, in which she described tender scenes fishing and hunting with Ernest and admitted her desire to be a ‘Hemingway hero’ like the protagonists of her father’s books. Though her attitude toward her father in Papa is one of forgiveness and even reverence, she does reveal moments where her childhood sensibilities came in conflict with Ernest. ‘I never saw him work,’ she writes of her irascible father after his move to Cuba. ‘I had doubts mixed with hero worship. Although I suppressed them as much as possible, they kept popping to the surface. Was he a phony? He was always talking about his work, but when did he do it?’ Of Gloria, Hemingway said she had ‘the biggest dark side in the family except me’.

Gloria’s addiction issues had always been a source of tension in her family. A 2003 Guardian article reported that Pauline Pfeiffer, Hemingway’s second wife and Gloria’s mother, ‘collapsed during a phone row with Ernest about [Gloria’s] drug-taking’. (It was Hemingway who’d encouraged Gloria to start drinking: ‘From the time I was ten or eleven, he let me drink as much as I wanted, having confidence that I would set my own limits,’ she writes in Papa.) Gloria and Hemingway blamed each other, and Gloria wrote letters referring to her father as an ‘ailing alcoholic’ and to The Old Man and the Sea as ‘a sickly bucket of sentimental slop’. A middle-aged Gloria was arrested in Key Biscayne after she had taken off her pink dress, underwear and heels to wander the street naked. She died of high blood pressure and heart disease in her cell in the Miami-Dade County Women’s Detention Center in 2001. Her once-divorced, twice-married wife Ida fought to claim the bulk of Gloria’s estate on the grounds that they had remarried after Gloria’s surgery. A Miami-Dade circuit judge challenged the claim on the basis that same-sex marriage was illegal. Along with Gloria’s placement in the women’s detention center, the judge’s arbitration would be the second and final public acknowledgment of her gender.

I have met people like Gloria before. None of them, as far as I know, live in the shadow of an internationally famous father, but all of them have lived big lives. They show up in support groups and writing groups and social spaces full of radical young queers. They’ve lived through adversity and emerged unbroken, which is to say they’re all getting by, hustling, even thriving. Which is to say, they haven’t succumbed to the badness. I told a few of them about Gloria and they were solemn: had the world she lived in been different, her life wouldn’t have ended so tragically. I was solemn, too – not only because of the tragedy of Gloria’s death but because the various subjectivities that so heavily influence my own life and art are the very same ones that undid her. There is something to be said here about the generation I was born into, the class I was born into, the whiteness I was born into – these things grease the wheels of my own happiness. But in discussions with my friends about Gloria, there was no careful calculus, as there so often is, to determine the exact advantages and disadvantages of her subject-position. Instead, the blame for the trauma of her life fell squarely on the head of her hypermasculine, misogynistic, homophobic father.

But the story isn’t as simple as the gun-toting, rhino-shooting Hemingway archetype suggests it is. While the Hemingway household appears to have rigidly upheld the gender binary, Hemingway’s self-concept may have been more influenced by ideas of androgyny and gender-fluidity than he cared to admit during his lifetime. In his posthumously-published Garden of Eden, there is an obvious fascination with ‘going back and forth between sexes,’ as Mary puts it. The book is the story of Hemingway stand-in David Bourne on his honeymoon with gender-fluid Catherine, who cuts her hair like his and says, ‘I’m a girl, but now I’m a boy too and I can do anything and anything and anything.’ Catherine calls Bourne by her own name and gently force-feminizes him during sex. And, incredibly, he agrees to it:

During the night he had felt her hands touching him. And when he awoke it was in the moonlight and she had made the dark magic of the change again and he did not say no when she spoke to him and asked the questions and he felt the change so that it hurt him all through and when she was finished after they were both exhausted she was shaking and she whispered to him, ‘Now we have done it. Now we really have done it.’

It’s strange and kind of wonderful to think that there may have been the possibility in Hemingway’s life for a gender-fluid kinship with Gloria, but sad to think that this possibility went unrealized. Hemingway’s childhood was genderqueer – forced-genderqueer – in ways that have been well-documented. His mother Grace was adamant about dressing Ernest as a girl. ‘Though the Victorian custom of the day did call for young boys to wear dresses, the clothes that Grace selected for Ernest were more feminine than those worn by other male children of the era,’ writes Christopher D. Martin in his article Ernest Hemingway: A Psychological Autopsy of a Suicide. ‘He remained in this style of dress for several years beyond the span that most boys spent in dresses, and his hair was cut in a fashion more common for female children.’ Grace tried to pass Ernest off as the identical twin of his older sister Marcelline. She called him ‘summer girl’ and ‘Dutch dolly.’ Hemingway hated his mother, whom he called Fweetee. At age two, he said, ‘I not a Dutch dolly . . . bang, I shoot Fweetee.’ So the tired scholarship sometimes goes: Hemingway was humiliated and feminized as a child and grew up hating his selfish mother and hunting and fishing and womanizing to compensate for Grace’s ego-insults. But Grace praised young Ernest’s hunting and fishing as well, and he spent plenty of his childhood in boy-clothes. It seems more likely that Hemingway had his own understanding of gender-fluidity, which he subsequently incorporated into Garden of Eden. This is conjecture, but then all of history’s queer stories are conjecture. Unless, of course, they end in tragedy.

‘Femmingway’, by A.B. Art

‘I know there were hijinks with other matadors on the ranch,’ Bart Paul told me when we spoke about Sidney’s queerness. ‘Short-sheeting their beds, and so on. But it’s none of my business to speculate.’ Paul is 71 and his wife is from a family of cattle ranchers. In an author photo, he wears a four-gallon hat, a vest and a bandana, his thumbs hooked into his jean pockets, a lasso hanging on the wall behind him. He first became interested in writing about Sidney when he paid a friendly visit to a film director and amateur bullfighter named Budd Boetticher in the early 70s. Boetticher told him offhandedly that Sidney was ‘gored more times by his “nephews” than he was by any bull’. The remark stunned Paul. Feeling he’d crossed a line, Boetticher quickly followed up: ‘But Sidney was very, very brave. You could never take that away from him.’

Double-Edged Sword does speculate. Paul wonders what Sidney must have thought of Hemingway’s machismo, what Hemingway must have thought of Sidney’s queerness. In 1933, Hemingway published a short story collection called Winner Take Nothing in which appeared ‘Mother of a Queen’, a short story about a gay bullfighter. Biographers and aficionados have confirmed that the gay matador was based off José Ortiz, a close friend of Sidney’s. Paul speculates that Sidney must have gossiped to Hemingway about Ortiz. ‘To discuss the sexuality of another matador with Hemingway, especially one known to be a close friend, seems curious, a venture onto dangerous ground,’ Paul writes. ‘Was Sidney testing his friend’s reaction to the idea of a gay torero; was he indulging his friend’s homophobia to appear straight and disdainful as well; was he just toying with someone too thick to see the truth about Sidney himself?’ An acquaintance of Paul’s who’d been a bullfighting aficionado during Sidney’s time in the ring said that Sidney’s queerness had been an open secret, that he wasn’t the only gay matador and all that ultimately mattered was how be acquitted himself with the bulls. Sidney’s attempts to stay in the closet appear to have come across as awkwardly as his boasts of greatness. In Bullfighter from Brooklyn, he writes in an embarrassingly detached manner about having sex with an entire village of native Mexican women, sleeping between bouts and awakening to find another tribute and another and another. His Elviras and chorus girls never seemed to have fooled his family, nor his friends, nor his biographers.

It should have been, I think, that Sidney’s performance in the ring was enough to win him dignity, that speculations about his queerness were palace intrigue, not bitter jokes at the expense of a blowhard. At what point does Sidney get squashed beneath the homophobic thumb of history, jeered at for his eagerness to hide a dangerous identity? Cases such as these make me think of us Frumkins as a team and Sidney as its mascot. We are minor-league, of course, and as we walk onto the field it’s obvious that we’ve sewn our own uniforms. Our mascot jogs on after us and does his prancing and waving and then his costume falls apart and everyone laughs. There’s the man underneath, and what a funny man. A gay, redhead Jew who actually thought he could pull off the acrobatics of being a mascot, of making a legacy for the Frumkin family as enduring and total as Hemingway made for his own. But the detractors don’t really matter, and neither do the Frumkin-Hemingway comparisons, and neither does the sewn-together nature of our uniforms.

There is freedom in ambiguity. Gender-wise I am neither/nor. In Hemingway terms, I am both a Dutch dolly and a rhino hunter. Of course, people see what they want to see: I am a girl, not a rhino hunter, and it is not intriguing but rather ‘crazy’ that I’ve lived such a risk-taking life and buzzed my head and eaten on many days enough calories to feed two men. If I could, I would absolutely watch bullfights and catch massive marlins and be a war correspondent and try to hunt Nazi U-boats using the boat I’ve named after my girlfriend. I want to build myself up so big that pronouns don’t matter, that my body doesn’t matter: I want to be woman or man or neither whenever the mood suits me, to be to everyone what I am to those few people who avert their eyes and smile sheepishly when I tell them my stories over a drink. And I have freedom, yes, but I also have a duty-bound obligation not to be too messy, to be ‘good’ mental health-wise and always trying to get better, to select some set of pronouns and perform my politics across a variety of social media platforms. At least I’m not obligated to be the man a whole generation of men wanted to be, to hunt and fish and brawl and advise F. Scott Fitzgerald on how to satisfy Zelda. At least, if I want, I can be explicit about stepping outside my assigned gender – I don’t have to bury my fascinations in a posthumous book (conjecture, conjecture). And at least I am lucky in that my life doesn’t have to end in tragedy like Gloria’s.

I think the freest of us all is Sidney. Not in the closet, of course, but in the bullring. There he could simultaneously plunge a sword into an animal that was trying to kill him – the Frumkins are fond of saying that every bull was Abram – and wear a gorgeous, gilded suit of lights. He could be swift and brutal and light on his feet: he could summon the bull in his Brooklyn baritone and then scamper away. He could use capes beautiful enough to be evening wraps. In his suit, with his pigtail and his montera, he was pure potential: he could be masculine vanquisher or gold-embroidered fairy. He was both, actually, at all times, and nobody who came to see him fight thought any less of him for it. In fact, they demanded it of him.

Sources Consulted

Double-Edged Sword: The Many Lives of Hemingway’s Friend, the American Bullfighter Sidney Franklin, Bart Paul.

Death in the Afternoon, Ernest Hemingway.

Bullfighter from Brooklyn, Sidney Franklin.

The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway.

A Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway.

Garden of Eden, Ernest Hemingway.

Papa: A Personal Memoir, Gloria Hemingway.

‘El Único Matador,’ Lillian Ross.

Ernest Hemingway: A Biography, Mary Dearborn.

‘Ernest Hemingway: A Psychological Autopsy of a Suicide,’ Christopher D. Martin.

Peter F. Cohen, “‘I Won’t Kiss You . . . I’ll Send Your English Girl’: Homoerotic Desire in A Farewell to Arms.” Hemingway Review 15.1 (Fall 1995).

Lillian Ross, Obituary, New York Times.

Gloria Hemingway, Obituary, New York Times.

Sidney Franklin, Gay Victim of Francoist Repression, RTVE.

Transsexual Marriage Contested by Children, Jacqui Goddard, the Guardian.

Death in the Arena: The Goring and Death of the Bullfighter Manuel Manolete, Sterling Films.

Special thanks to Doris Markowitz, Bart Paul, Mary Dearborn, Michael Frumkin, William Frumkin, Laney Silver, Harriet Amato, Paula Frumkin and all the Frumkin cousins. In memory of Judy Fox.

Cover Illustration © Tom Bachtell