A few days before I left Luanda, I was taken by American friends to dine in a black-market restaurant. We ate at outside tables in a little enclosure on the street. The clientele all looked more or less as if they were black-market profiteers themselves. We were sitting right next to the rail that fenced us in from the street, and I had my back to this, so that, absorbed in conversations, I did not notice at first that a crowd had gathered behind us and were reaching in to grab things from our plates. But the management soon sent out a bouncer, who knocked down an old woman with a blow on the head and drove back the mob, mostly women and children, some of whom disappeared, while others, keeping their distance, stood dumbly and stared at the diners.

Here in Beirut refugees are lying on all the steps, and one has the impression that they would not look up even were a miracle to take place in the middle of the square; so certain are they that none will happen. One could tell them that some country beyond the Lebanon was prepared to accept them and they would gather up their boxes, without really believing. Their life is unreal, a waiting without expectation, and they no longer cling to it: rather, life clings to them, ghostlike, an unseen beast which grows hungry and drags them through ruined railway stations, day and night, in sunshine and in rain; it breathes in the sleeping children as they lie on the rubble, their heads between bony arms, curled up like embryos in the womb, as if longing to return there.

Unsettling about this place in the North of Sri Lanka is not that one fears being molested – at any rate not during the day – but, rather, because of the sure knowledge that people of one’s own sort, if suddenly faced with living this kind of life, would go under within three days. One feels very keenly that even a life like this has its own laws, and it would take years to learn them. A truck full of policemen; at once they scatter, some stand still and grin, while I look on and have no idea what is happening. Four boys and three girls are loaded into the truck, where they squat down among others who have already been picked up elsewhere. Indifferent, impenetrable. The police have helmets and automatics, therefore authority, but no knowledge. The newspapers carry a daily column of street attacks, sometimes naked corpses are discovered, and the murderers come as a rule from the other side. Whole districts without a single light. A landscape of brick hills, beneath them the buried, above them twinkling stars; nothing stirs there but rats.

Reports from the Third World, such as we can read every morning over breakfast. The place names are false, however. The locations are not, in fact, Luanda, Beirut and Trincomalee; they are Rome, Frankfurt-am-Main and Berlin. Only forty-five years separate us from conditions we have become accustomed to thinking of as African, Asian or Latin American.

At the end of the Second World War Europe was a pile of ruins, not merely in a physical sense; it seemed totally bankrupt in political and moral terms. It was not only the defeated Germans for whom the situation seemed hopeless. When Edmund Wilson came to London in July 1945, he found the English in a state of collective depression. The mood of the city reminded him of the cheerlessness of Moscow: ‘How empty, how sickish, how senseless everything suddenly seems the moment the war is over! We are left flat with the impoverished and humiliating life that the drive against the enemy kept our minds off. Where our efforts have all gone toward destruction, we have been able to build nothing at home to fall back on amidst our own ruin.’

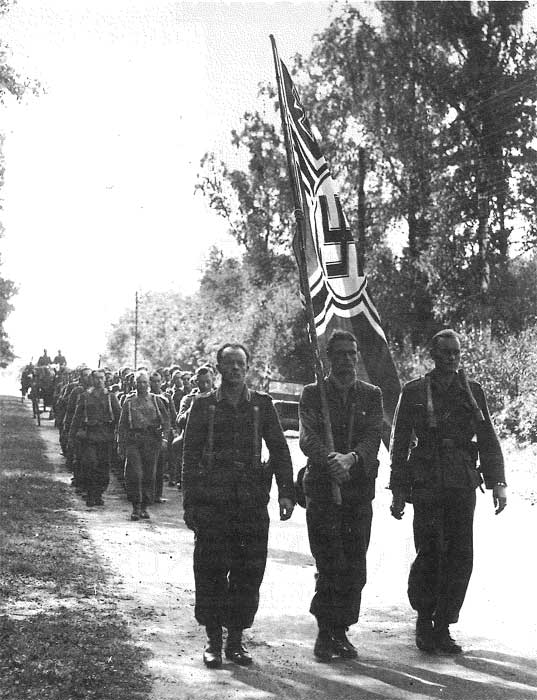

German troops surrendering, 1944

No one dared believe that the devastated continent could have a future. It seemed as if the history of Europe had come to an end with an overwhelming act of self-destruction, which the Germans had initiated and completed with savage energy: ‘This is what exists,’ noted Max Frisch in the spring of 1946, ‘the grass growing in the houses, the dandelions in the churches and suddenly one can imagine, how it might all continue to grow, how a forest might creep over our cities, slowly, inexorably, thriving unaided by human hands, a silence of thistles and moss, an earth without history, only the twittering of birds, spring, summer and autumn, the breathing of years which there is no one to count any more.’

If someone had prophesied to the cave-dwellers of Dresden or Warsaw of those days a future like that of 1990, they would have thought him crazy. But for people today their own past has become just as unimaginable. They have long repressed and forgotten it and those who are younger lack the imagination and the knowledge to make a picture of earlier times. It grows increasingly difficult to imagine the condition of our continent at the end of the Second World War. The storytellers, apart from Böll, Primo Levi, Hans Werner Richter, Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Curzio Malaparte and a few others, capitulated before the subject; the so-called Trümmerliteratur – literature of the ruins – hardly delivered what it promised.

Period newsreels show monotonous pictures of destruction; the soundtrack consists of hollow phrases; the films provide no indication of the inner state of men and women in the devastated cities. The memoir literature that emerged later lacks authority. This is not only because of the urge to touch things up which is so frequent in the genre of autobiography, or because the authors usually tend towards self-justification and self-accusation. It is not their integrity that is questionable, but their perspective. In looking back, they lose the very thing which should matter most: the coincidence of the observer with what he is looking at. The best sources tend to be the eyewitness accounts of contemporaries.

Anyone studying the eyewitness reports will, however, have an odd experience. A key feature of the post-war period is a strange ignorance, a narrowing of horizons, that is unavoidable under extreme living conditions. At best it is a straightforward lack of knowledge of the world, easily explained by the years of isolation. John Gunther writes of a young soldier in Warsaw, with whom he entered into conversation on a summer evening in 1948: ‘There was no nonsense about him. He knew exactly what Poland had suffered and what he himself had suffered. His ignorance of the outside world was, however, considerable. He had never met an American before. He wanted to know if New York had been made kaputt by the war like Warsaw.’

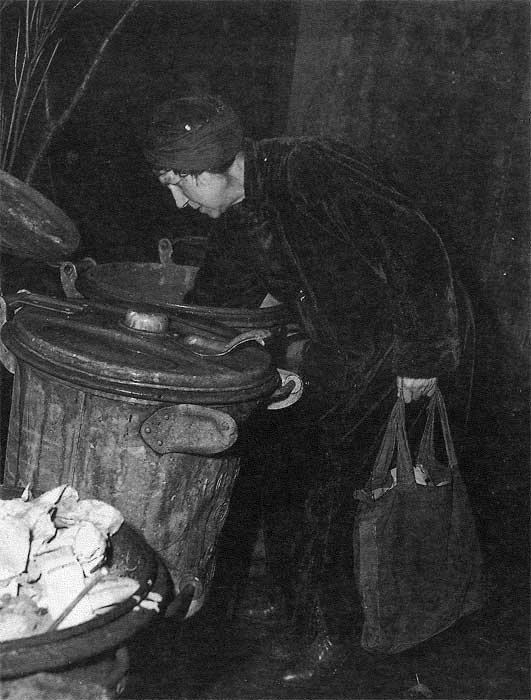

Berlin, 1945

Americans were looked at as if they were men from Mars, and their belongings were treated with a reverence reminiscent of the cargo cults of Polynesia. Europeans displayed attitudes like those found in the Third World. Someone who is thinking only of the next meal, who is forced to build a roof over his own head, will lack the desire and energy to make himself aware and well-informed. The restricted vision was compounded by the absence of freedom of movement. Millions were on the move, but only to save their skins. Travel in the usual sense of the word was not possible.

In the first years after the war the long-term consequences of the Fascist dictatorship were becoming evident, not only in Germany but throughout Europe. Europeans took shelter behind a collective amnesia. Reality was not just ignored; it was flatly denied. With a mixture of lethargy, defiance and self-pity they regressed to a kind of second childhood. Anyone meeting this syndrome for the first time was astonished; it seemed to be a form of moral insanity. When she visited the Rhineland in April 1945, the American journalist Martha Gellhorn was exasperated, indeed staggered, by the statements of the Germans she met:

No one is a Nazi. No one ever was. There may have been some Nazis in the next village, and as a matter of fact, that town about twenty kilometres away was a veritable hotbed of Nazidom. To tell you the truth, confidentially, there were a lot of Communists here. We were always known as very Red. Oh, the Jews? Well, there weren’t really many Jews in this neighbourhood. Two, maybe six. They were taken away. I hid a Jew for six weeks. I hid a Jew for eight weeks. (I hid a Jew, he hid a Jew, all God’s chillun hid Jews.) We have nothing against the Jews; we always got on well with them. We have had enough of this government. Ah, how we have suffered. The bombs. We lived in the cellars for weeks. We welcome the Americans. We do not fear them; we have no reason to fear. We have done nothing wrong; we are not Nazis.

It should, we feel, be set to music. Then the Germans could sing this refrain and that would make it even better. They all talk like this. One asks oneself how the detested Nazi government, to which no one paid allegiance, managed to carry on this way for five and a half years. Obviously not a man, woman or child in Germany ever approved of the war for a minute, according to them. We stand around looking blank and contemptuous and listen to this story without friendliness and certainly without respect. To see a whole nation passing the buck is not an enlightening spectacle.

More than two years later Janet Flanner comes to similar conclusions:

The new Germany is bitter against everyone else on earth, and curiously self-satisfied. Bursting with complaints of her hunger, lost homes, and other sufferings, she considers without interest or compassion the pains and losses she imposed on others, and she expects and takes, usually with carping rather than thanks, charity from those nations she tried to destroy . . . The significant Berlin catch-all phrase is ‘That was the war, but this is the peace.’ This cryptic remark means, in free translation, that the people feel no responsibility for the war, which they regard as an act of history, and that they consider the troubles and confusions of the peace the Allies’ fault. People here never mention Hitler’s name any more. They just say darkly ‘Früher war es besser’, (things were better before), meaning under Hitler. Only a few Germans seem to remember that, beginning with the occupations of 1940, some of them had the sense to launch the slogan ‘Enjoy the war. The peace will be terrible.’ It is.

So much for the state of consciousness of the Germans. Other Europeans were no less deluded. John Gunther reports: ‘I asked one responsible Greek politician what the solution was, if any, and he replied in one word, “War.” Indeed many conservative Greeks feel that nothing but outright war between the United States and the Soviet Union can rescue them; they actively want a war, horrible as this may seem, and make no bones about it. I asked my friend: “But do you think there is going to be a war?” He answered: “Europe is in anarchy. One hundred million people are slaves. We have to have war. There must be a war, or we will lose everything.”’

Anyone who turns to published opinion of the time in the hope of gaining a clearer picture of post-war Europe faces further disappointments. Sober verdicts, intelligent analyses, convincing reportage are hardly to be found in the newspaper and magazine columns of the years 1945–48. That is not solely due to restrictions imposed by the occupying powers. The internal self-censorship of journalists was of much greater consequence. The Germans distinguished themselves in this respect too. Most intellectuals failed to bear witness to the facts and fled into abstraction. One searches in vain for the great reportage. What one finds, along with philosophical generalizations on the theme of collective guilt, are invocations of the Western tradition, of Goethe, humanism, the forgetfulness of being and the ‘idea of freedom’. These exercises seem to indicate a near total loss of reality.

For all of these reasons little reliance can be placed on the testimony of participants in the events in Europe. One must go to other sources to gain an accurate picture of post-war conditions. The most trustworthy source is the gaze of the outsider. The most acute reports were provided by authors who accompanied the victorious Allied armies. The finest among them are the American reporters, journalists like Janet Flanner and Martha Gellhorn and writers like Edmund Wilson, who did not feel superior to the press. They were part of the great Anglo-Saxon tradition of literary reportage – the Europeans have, until now, failed to produce anything to equal it. Other valuable sources were the product of chance, like the confidential reports of an American editor who worked for the US secret service, or the notes of émigrés who attempted to return to the Old World. Authors from countries which the war had spared, like the Swiss Max Frisch and the Swedish novelist Stig Dagerman, also made contributions.

Aachen, 1945

All of these witnesses came from a world which was similar to ours: orderly, normal, characterized by the thousand things taken for granted in a functioning civil society. The sense of shock that the European disaster produced in them was all the greater for the contrast with their experience at home. They could hardly trust their eyes before the brutal, eccentric, terrifying and moving scenes which they experienced in Paris and Naples, in the villages of Crete and the catacombs of Warsaw. The stranger’s gaze is able to make us comprehend what was happening in Europe then; it does not rely on the linguistic rules of ideology, but on the telling physical detail. While the leading articles and policy statements of the period have a strange mustiness about them, the eyewitness reports remain fresh.

The specialists in perception are at their best when they generalize least, when they do not censor the fantastic contradictions of the chaotic world through which they are moving, but leave them as they are. Max Frisch concludes his notes on Berlin with a laconic remark that silences all critical argument: ‘A landscape of brick hills, beneath them the buried, above them the twinkling stars; nothing stirs there but rats. – Evening at the theatre: Iphigenia.’

Essen, 1946

A good example of the astonishing foresight that emerges in the texts of the outsiders is Martha Gellhorn‘s reportage of July 1944. It was a time when not a soul in Washington was thinking about the Cold War. In the middle of an artillery duel in a village on the Adriatic, Martha Gellhorn converses with soldiers of a Polish unit fighting against the Germans:

They had come a long way from Poland. They call themselves the Carpathian Lancers because most of them escaped from Poland over the Carpathian mountains. They had been gone from their country for almost five years. For three and a half years this cavalry regiment, which was formed in Syria, fought in the Middle East and the Western Desert. Last January they returned to their own continent of Europe, via Italy, and it was the Polish Corps, with this armoured regiment fighting in it as infantry, that finally took Cassino in May. In June they started their great drive up the Adriatic, and the prize, Ancona – which this regiment had entered first – lay behind us.

It is a long road home to Poland, to the great Carpathian mountains, and every mile of road has been bought most bravely. But now they do not know what they are going home to. They fight an enemy in front of them and fight him superbly. And with their whole hearts they fear an ally, who is already in their homeland. For they do not believe that Russia will relinquish their country after the war; they fear that they are to be sacrificed in this peace, as Czechoslovakia was in 1938. It must be remembered that almost every one of these men, irrespective of rank, class or economic condition, has spent time in either a German or a Russian prison during this war. It must be remembered that for five years they have had no news from their families, many of whom are still prisoners in Russia or Germany. It must be remembered that these Poles have only twenty-one years of national freedom behind them, and a long aching memory of foreign rule.

So we talked of Russia and I tried to tell them that their fears must be wrong or there would be no peace in the world. That Russia must be as great in peace as she has been in war, and that the world must honour the valour and suffering of the Poles by giving them freedom to rebuild and better their homeland. I tried to say I could not believe that this war which is fought to maintain the rights of man will end by ignoring the rights of Poles. But I am not a Pole; I belong to a large free country and I speak with the optimism of those who are forever safe. And I remember the tall gentle twenty-two-year-old soldier who drove me in a jeep one day, and how quietly he explained that his father had died of hunger in a German prison camp, and his mother and sister had been silent for four years in a labour camp in Russia, and his brother was missing, and he had no profession because he had entered the army when he was seventeen and so had had no time to learn anything. Remembering this boy, and all the others I knew, with their appalling stories of hardship and homelessness, it seemed to me that no American had the right to talk to the Poles, since we had never even brushed such suffering ourselves.

The editors of Collier’s magazine, for which Martha Gellhorn was working, refused to publish this report, because the Poles’ prophetic remarks about the Soviet Union, the United States’ most important ally, did not suit them.

What makes the work of these reporters so illuminating is not that they lay claim to a higher objectivity, but the reverse, that they hold on to their radically subjective viewpoint. This is true even when – yes, especially when – they put themselves in the wrong. Among the costs of immediacy is that one is infected by one‘s surroundings and cannot stand above them. The sore points from the post-war years emerge all the more clearly; the frictions between English and Americans, the fury of the victors at the grandiose impudence of the Neapolitans, above all the hatred of the Germans, which in some observers mounts to disgust and a desire for revenge. Whoever had behaved like the Germans and continued to behave like them – that is, outside all reason – could not expect any fairness; almost all representatives of the victorious nations were convinced of that, and it is by no means superfluous to remind oneself of the extreme expressions of feeling during those years.

Berlin, 1947

The observers from neutral countries are more ambivalent in their judgements. Not that one could accuse them of special sympathy for the Germans; but they are more able than the victors to perceive their own role. After a visit to Germany in the autumn of 1946, the Swede Stig Dagerman writes:

If any commentary is to be risked on the mood of bitterness towards the Allies, mixed with self-contempt, with apathy, with comparisons to the disadvantage of the present – all of which were certain to strike the visitor that gloomy autumn – it is necessary to keep in mind a whole series of particular occurrences and physical conditions. It is important to remember that statements implying dissatisfaction with or even distrust of the goodwill of the victorious democracies were made not in an airless room or on a theatrical stage echoing with ideological repartee but in all too palpable cellars in Essen, Hamburg or Frankfurt-am-Main. Our autumn picture of the family in the waterlogged cellar also contains a journalist who, carefully balancing on planks set across the water, interviews the family on their views of the newly constituted democracy in their country, asks them about their hopes and illusions, and, above all, asks if the family was better off under Hitler. The answer that the visitor then receives has this result: stooping with rage, nausea and contempt, the journalist scrambles hastily backwards out of the stinking room, jumps into his hired English car or American jeep, and half an hour later over a drink or a good glass of real German beer, in the bar of the press hotel composes a report on the subject ‘Nazism is alive in Germany’.

Frankfurt, 1947

Fifty years after the catastrophe Europe understands itself more than ever as a common project, yet it is far from achieving a comprehensive analysis of the years immediately following the Second World War. The memory of the period is incomplete and provincial, if it is not entirely lost in repression or nostalgia. People were busy with their own survival and could not bother with larger events; now they are reluctant to talk about skeletons in the cupboard. They prefer to address the glowing future of the Common Market or the opening up of Eastern Europe, instead of thinking about the unpleasant times when no one would have put a brass farthing on a rebirth of our peninsula. This is a fatal strategy; in retrospect it appears that during the years 1944–48, without the participants suspecting it, the seeds were sown not only of future successes but also of future conflicts.

A high-explosive bomb is a high-explosive bomb, a desperate hunger does not distinguish between black and white, just and unjust, but neither the destructive power of the air forces nor the post-war misery was capable of homogenizing Europe and extinguishing its differences. What was not visible in the burnt earth proved to be of considerable consequence: the tenacious ability to survive of the immaterial structures which had, as it were, hibernated in people’s heads. The European societies were like cities which had been destroyed, but for which detailed construction diagrams and land registers had been preserved; their invisible connections and network plans had survived the destruction. Differences in traditions, capacities, mentalities endured and re-emerged.

As Norman Lewis wrote in his Naples reportage of 1944:

It is astonishing to witness the struggles of this city so shattered, so starved, so deprived of all those things that justify a city‘s existence, to adapt itself to a collapse into conditions which must resemble life in the Dark Ages. People camp out like Bedouins in deserts of brick. There is little food, little water, no salt, no soap. A lot of Neapolitans have lost their possessions, including most of their clothing, in the bombings, and I have seen some strange combinations of garments about the streets, including a man in an old dinner-jacket, knickerbockers and army boots, and several women in lacy confections that might have been made up from curtains. There are no cars but carts by the hundred, and a few antique coaches such as barouches and phaetons drawn by lean horses. Today at Posilippo I stopped to watch the methodical dismemberment of a stranded German halftrack by a number of youths who were streaming away from it like leaf-cutter ants, carrying pieces of metal of all shapes and sizes. Fifty yards away a well-dressed lady with a feather in her hat squatted to milk a goat. At the water‘s edge below, two fishermen had roped together several doors salvaged from the ruins, piled their gear on these and were about to go fishing. Inexplicably no boats are allowed out, but nothing is said in the proclamation about rafts. Everyone improvises and adapts.

The attitudes that Lewis describes have remained characteristic of the population of southern Italy up to the present day: an ingenuity which knows how to take advantage of every opening, a parasitism of quite heroic energy and an untiring readiness to exploit a hostile world. The priorities of the French were, and still are, quite different. In February 1945 Janet Flanner writes:

The brightest news here is the infinite resilience of the French as human beings. Parisians are politer and more patient in their troubles than they were in their prosperity. Though they have no soap that lathers, both men and women smell civilized when you encounter them in the Métro, which everybody rides in, there being no buses or taxis. Everything here is a substitute for something else. The women who are not neat, thin, and frayed look neat, thin, and chic clattering along in their platform shoes of wood – substitute for shoe leather – which sound like horses‘ hoofs. Their broad-shouldered, slightly shabby coats of sheepskin – substitute for wool cloth which the Nazis preferred for themselves – were bought on the black market three winters ago. The Paris midinettes, for whom, because of their changeless gaiety, there is really no substitute on earth . . . still wear their home-made, fantastically high, upholstered Charles X turbans. Men’s trousers are shabby, since they are not something which can be run up at home. The young intellectuals of both sexes go about in ski clothes. This is what the resistance wore when it was fighting and freezing outdoors in the maquis, and it has set the Sorbonne undergraduate style.

The more serious normalities of traditional Paris life go on, in readjusted form. Candy shops display invitations to come in and register for your sugar almonds, the conventional sweet for French baptisms, but you must have a doctor’s certificate swearing that you and your wife are really expecting. Giddy young wedding parties that can afford the price pack off to the wedding luncheon two by two in vélo-taxis, bicycle-barouches which are hired for hundreds of francs an hour. The other evening your correspondent saw a more modest bridal couple starting off on their life journey together in the Métro. They stood apart from everyone else on the Odéon platform, the groom in his rented smoking and with a boutonnière, the bride all in white – that is, a white raincoat, white rubber boots, white sweater and skirt, white turban, and a large, old-fashioned white nosegay. They were holding hands. American soldiers across the tracks shouted good wishes to them.

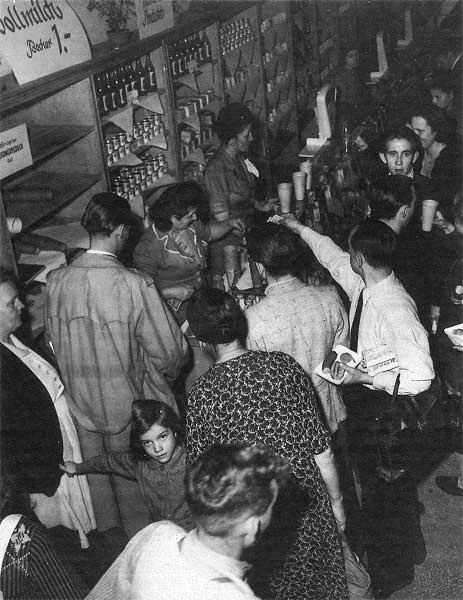

Berlin, 1949

Of course the descriptions express the prejudices and idées reçues of the observers. But they also rise above conventional thinking. The following reportage by John Gunther flies in the face of almost every cliché about the Poles.

This concentrated tornado of pure useless horror turned Warsaw into Pompeii. I heard a serious-minded Pole say, ‘Perhaps a few cats may have been alive, but certainly not a dog.’ After liberation early in 1945 the Polish government took the heroic decision to rebuild. This was a herculean step, and Poles nowadays laugh about it with a peculiar rough tenderness, saying that the reason must have been their ‘romanticism’. Even ministers as powerful as Hilary Mine thought that it would be impossible to rebuild, and suggested starting from scratch with a new capital at Lodz. He was outvoted. The decision to rebuild Warsaw, and keep it the capital no matter at what cost, was of course wise – and not romantic at all – in that it gave the patriotic focus and an urgent aggressive faith to the workings of the new regime . . .

Every Pole I met was almost violent with hope. ‘See that?’ A cabinet minister pointed to something that looked like a smashed gully. ‘In twenty years time that will be our Champs Elysées.’

Particularly impressive is [the work of rebuilding] in the Old City, which is almost as complete a ruin as the ghetto. A patch of ravaged brick is all that remains of the Angelski Hotel where Napoleon stayed. The old bricks are used in the new structures, which gives a crazy patchwork effect. Hundreds of houses are only half rebuilt; as soon as a single room is habitable, people move in. I never saw anything more striking than the way a few pieces of timber shore up a shattered heap of stone or brick, so that a kind of perchlike room or nest is made available to a family, high over crumbling ruins. One end of a small building may be a pile of dust; at the other end you will see curtains in the windows.

Much of this furious reconstruction is done by voluntary labour; most, moreover, is done by human hand. Even cabinet ministers go out and work on Sunday. In all Warsaw, there are not more than two or three concrete mixers and three or four electric hoists; in all Warsaw, not one bulldozer! A gang of men climb up a wall, fix an iron hook on the end of a rope to the topmost bricks, climb down and pull. Presto! – the wall crashes. Then some distorted bricks go into what is going up. The effect is almost like that of double exposure in a film. No time for correct masonry!

So this catastrophically gutted city, probably the most savage ruin ever made by the hand of evil mankind anywhere, is being transformed into a new metropolis boiling and churning with vigour. Brick by brick, minute by minute, hand by hand, Warsaw is being made to live again through the fixed creative energy and imagination of an immensely gifted and devoted people.

Another writer observed the beginnings of German reconstruction on a journey through southern Germany. The reflections which Alfred Döblin set to paper have lost none of their force over the past decades.

A principal impression made by the country, and it provokes the greatest astonishment in someone arriving at the end of 1945, is that the people are running back and forward in the ruins like ants whose nest has been destroyed. Agitated and eager to work, their major grievance is that they cannot set to immediately, because of the absence of materials, the absence of directives.

The destruction does not make them depressed, but acts as an intense stimulus to work. I am convinced: If they had the means that they lack, they would rejoice tomorrow, only rejoice, that their old, out-of-date, badly laid out towns have been destroyed and that now they have been given the opportunity to put down something first-class, altogether modern . . .

In Stuttgart people talk to me and show me certain groups of buildings and state: that was this air raid or that air raid and recount certain episodes. And that is all. No particular information follows, and there are certainly not any further reflections. People go to their work, stand in queues here, as everywhere else, for food.

Already there are theatres, concerts and cinemas here and there and I hear, all have large audiences. The trams are running, horribly full as everywhere. People are practical and help one another. They worry about today and tomorrow in a way that is already troubling the thoughtful.

The countryside looks cared for. Only the cities are devastated. And how devastated. Out in America one has seen pictures of these cities in the cinemas. One can walk along the streets of many cities, the roadway and often the pavement too has been cleared. Almost everywhere the usable bricks have already been sorted out and neatly piled against the walls of buildings. They await a new use. For as I already said, here lives as before an industrious, orderly people. They have, as always, obeyed a government, finally that of Hitler, and by and large do not understand, why this time obedience is supposed to have been bad. It will be much easier to rebuild their cities than to make them experience, what they have experienced and to understand how it came about.

East Germany, 1949

One may find it unjust that the verdict on the reconstruction efforts of the people of Stuttgart is so ill-humoured by comparison with the praise bestowed on the rebuilding of Warsaw. But one cannot understand the puzzling energy of the Germans if one resists the idea that they have turned their defects into virtues. They had, in a quite literal sense, lost their minds and that was the condition of their future success. The tricky quality of this relationship emerges in the following report by Robert Thompson Pell, an American secret service officer, who in the spring of 1945 was faced with examining the activities during the Third Reich of the top managers of the I. G. Farben company.

On the whole I gained the impression that the German leaders had gone over to accommodating themselves to necessity – that, however, only to a limited degree. In the meanwhile they are sounding out our weak points, putting us to the test at every opportunity, trying to find out if we really mean it when we thump the table, and offering as much resistance as they dare. They say almost openly, we will not be able to cope with the situation ourselves and will have to turn to them again in the end. They are relying on us making so many mistakes that it will be inevitable that they take charge again. Till then they will bide their time and look on, while we bungle everything. Apart from that they play up the ‘red peril’ as much as they dare. As soon as one shows oneself to be even a little approachable – or if they believe they can see signs of it – they tell us again and again: ‘We are so glad that you are here and not the Russians,’ and in a few cases they’ve actually maintained that the German army withdrew so that we could save as much of West Germany from the Russians as could be saved.

The directors whom I fetched in my jeep every day were itching to tell me that the German people had been the victim of a worldwide conspiracy which had intended to deliver up this lovely country to unknown forces; Germany had conducted a defensive war; the Allied ‘terror raids’ had united the German people, had no military value and had been a serious error; they were the true defenders of Western civilization against ‘the Asiatic hordes’ etc.

In short, the country was in chaos and the people were in a hysterical condition, which quickly grew into an attitude of defiance and a feeling of being treated unjustly, and which was not clouded by the least trace of guilt. Most of these men of high and in some cases the highest standing in society were ready to admit, that Germany had lost the war, but were quick to add the reason was the superiority of the Allies in power and material; they then immediately added in future they would try to make that good. The overall impression was, in short, disquieting. So far as I could ascertain, the attitude of the average manager was characterized by self-pity, fawning self-justification and an injured sense of innocence, which was accompanied by a yammering for pity and for aid in the reconstruction of his devastated country. Many of them, if not the majority, confidently expect that American capital will commit itself without delay to the work of reconstruction, and they declared themselves ready to place their labour power and their intellect at the service of these temporary masters; as a consequence they openly expect to rebuild a Germany more powerful and bigger than it was in the past.

These delusions of 1945 have since become, in a rather roundabout way, reality, and the implicit historical irony has turned into a sneer. That those who were defeated, the Germans and the Japanese, today feel like victors is more than a moral scandal; it is a political provocation. Our leaders never tire of protesting that in the meantime we have all become peaceable, democratic and moderate; in a word, well-behaved. The most remarkable thing about this assertion is that it is true. The form that this mutation has taken with the Germans is to have turned them into a nation of shopkeepers. In that they are by no means alone. All the nations of Europe are with varying success trying to do the same. The German suicide attempt has failed, as has that of Europe as a whole. But the more our peninsula moves back into the centre of world politics and of the world market, the more a new kind of Eurocentrism will gain ground. A slogan that was copyrighted by Joseph Goebbels has reappeared in public debate: ‘Fortress Europe’. It was once meant in a military sense; it has returned as an economic and demographic concept. A Europe in renewal will do well to remind itself of Europe in ruins, from which it is separated by only a few decades.

The Max Frisch quotations are from his Sketchbook: 1946–1949, translated by Geoffrey Skelton (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich 1977).

Photographs © PhotosNormandie, Popperfoto, Hulton-Deutsch Collection, Hulton-Deutsch Collection, Popperfoto, Popperfoto, Popperfoto, Popperfoto, Popperfoto