En Route to The Promised Land

Ken Light

Photographs © Ken Light/Contact Press Images

An Unwanted Sense of Déjà Vu

It has been said that journalism is the ‘first rough draft of history’, and so it made sense for me, a documentary photographer, who extensively photographed on the US–Mexico border in the early 80s, to return to my contact sheets – a photographer’s first rough draft of history.

I went back to review my work, to remind and inspire me, perhaps to spur me on to return to the border thirty years later, to better understand why immigration continues to be a thorn in the side of American politics. To re-examine older work one invariably glimpses different messages, or aspects of the story you couldn’t perceive when editing in the moment.

Back then, I was photographing for my book To The Promised Land (Aperture, 1988). I had been compelled to tell the story of the waves of desperate people trying to reach America. I was motivated both by seeing first-hand the faces and sensing the desperation along the border, but also by the fact that my immigrant family, which arrived from Eastern Europe in the 1880s, had no visual record of its journey. The story for me was very personal; despite the ascendancy of TV, the power of still photography was undeniably persuasive and I would use it as I had before.

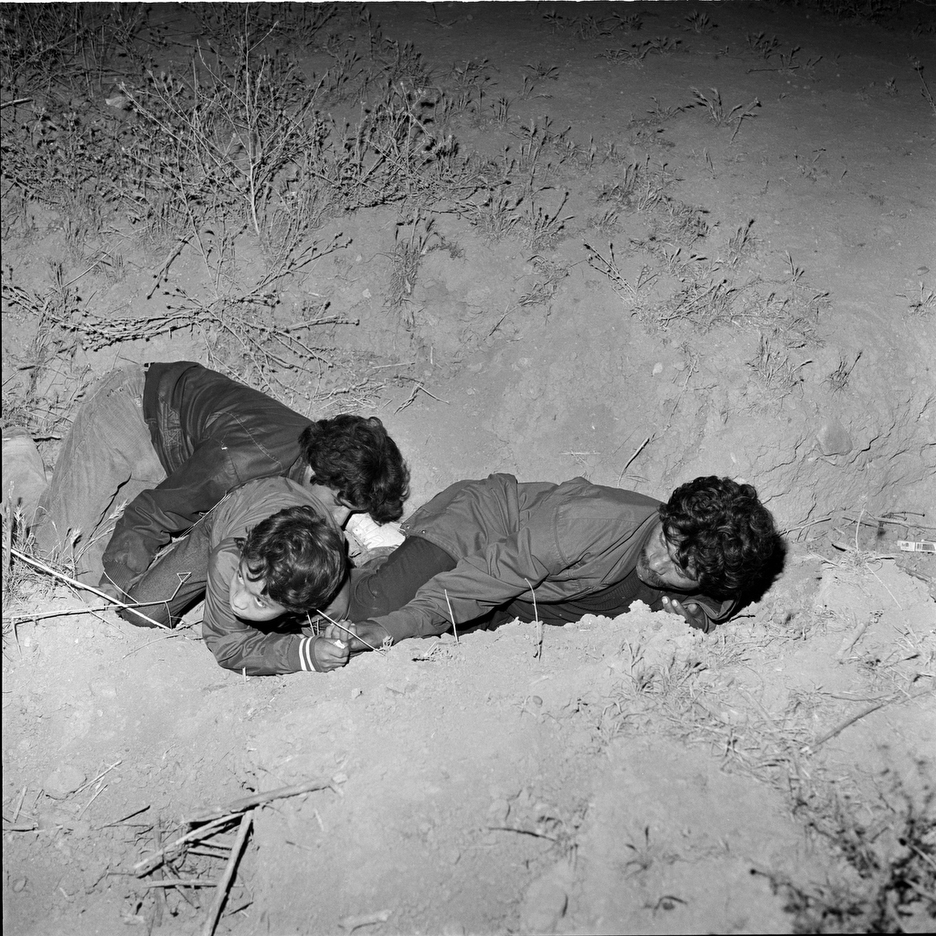

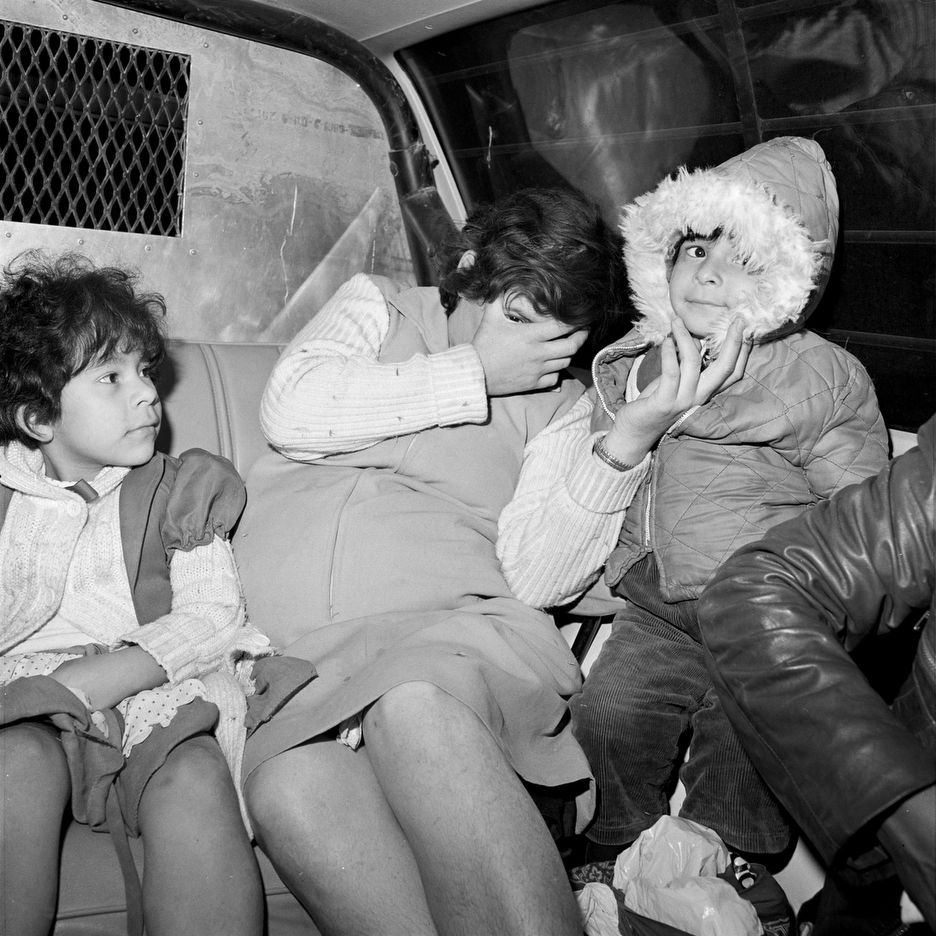

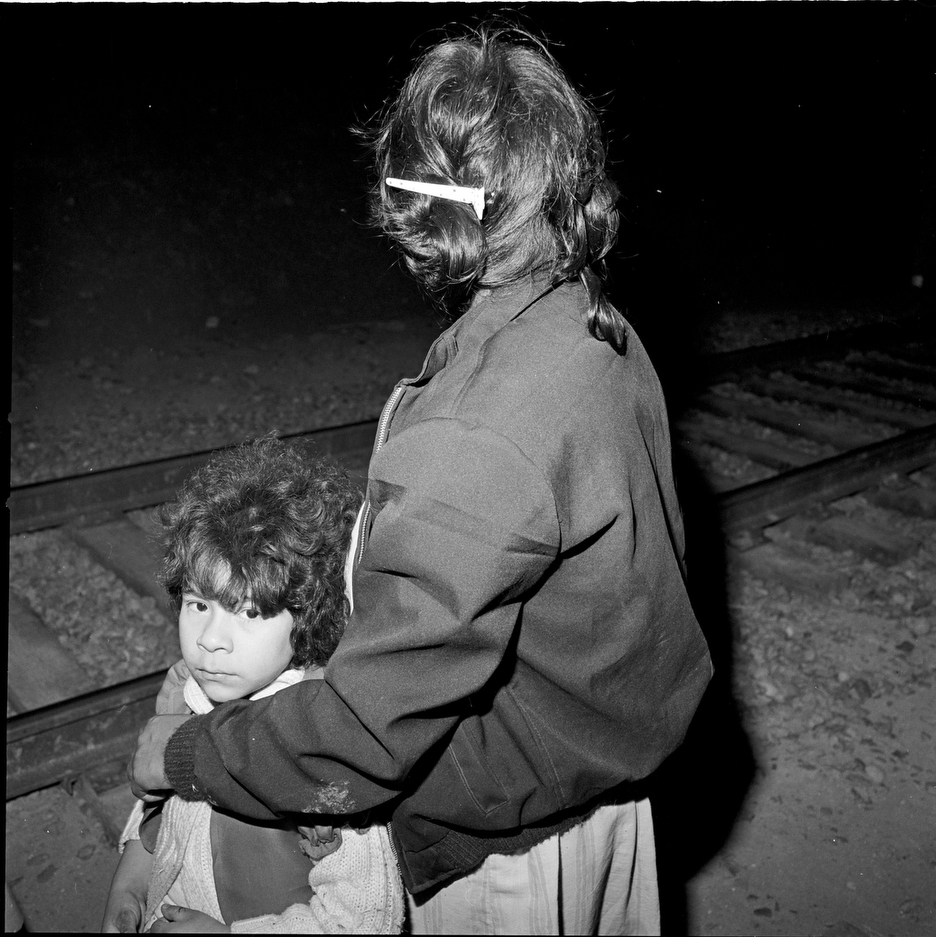

On my first visit to the border in 1983 I was overwhelmed by what I witnessed. I photographed grown men hiding in bushes, crawling through tunnels, grandfathers with their hands held high in plaintive surrender, the wounds of a man beaten by bandits. Yet the saddest moments were those I spent with children – exhausted and caught in the middle – mothers and daughters huddled together, not certain what would come next; a young boy, maybe ten, sitting alone in a paddy wagon looking sad and unsure. In those days, one had unfettered access with the Border Patrol; you could photograph what they saw as they saw it. The starkness of shooting at night, catching images with a strobe against the dark, had an immediacy, evoking the unvarnished Weegee and underscoring the struggle of those who had hiked for days, if not weeks.

Night after night, from 4 p.m. until after dawn, for weeks on end, I photographed the drama on the border, as people tried to cross into the United States, looking for ‘safe harbor’. Shooting at night was rough. Film cameras in the 80s had no auto-focus, through-the-lens metering, nor ultra-sensitive digital chips capable of shooting in low light like today. The border areas we traversed were pitch black; I could hardly see through my viewfinder much less focus. I had to rely on professional instinct and camera settings. I knew that within ten feet, my images would be sharp; if I moved beyond that, the flash would not deliver or the images would be blurry. Regardless, I was driven to spend months on this self-assigned project because I was witnessing a historic moment in the American immigration story, and I believed still photography was the most compelling medium with which to document it.

It has been unbearable, but at the same time fascinating, to see the current immigration crisis take us back to those earlier days on the border, as if time has been standing still. As I look back at the photos I took then, I can’t help but think of one of the photographers I often turn to for inspiration, Lewis Hine, who himself photographed American immigrants more than a hundred years ago. Our great social documentarians, storytellers like Hine or Dorothea Lange, give me a perspective on the journey America is still on. As I look at their images, I recognize the resolving power of photography, the way it can document our past, unfiltered, and allow historical events to resonate decades and even centuries later.

Lewis Hine documented immigration in the early 1900s at Ellis Island, and his powerful series of images of child labor – otherwise hidden from public view – visually stunned the nation. Photographs of breaker boys in the coalfields, doffer girls in America’s spinning mills, newsies and oyster shuckers, remind me of the images we are seeing now: small children, vulnerable to political winds, partisan-driven laws and abject greed. Children continue to be tossed about in our adult world like pawns. Moments such as we are witnessing now along the border echo my images from the 80s, and again force us to stare into the faces of children caught in a moment of great anguish. I keep having an unwanted sense of déjà vu.

Many of the photographs that were edited out of my book in the 80s, or which I then overlooked, have a new power, and a new meaning given the current crisis. The story is still alive, and these new found images provide historical context: the faces are the same, the story unchanged, and yet we are still grappling with a profound lack of human feeling, which we should have internalized after so many decades of fielding immigrants along our borders.

In an era when we are consumed by social media, photography can still shock and surprise. The still image allows a viewer to look deeply into a moment, without sound, edit cuts or camera roll – and that creates a different, more personal experience. A photograph stares you in the face, confronts you. When young children are caught in crisis, a single image has the power to activate deep emotions, and, I hope, to spark conversations that will lead to activism and policy change.