Ed left instructions in his will for the disbursement of certain objects and a great deal of art. I spent an afternoon in his studio in June 1993, helping him make these decisions. We were dry-eyed, strangely festive, even though a PICC that went into his arm, past his shoulder, and then a fraction of an inch into a chamber in his heart, was being replaced the next day by an apparatus that entered his chest. He said, ‘This week the mockingbirds returned. Their song is so pretty, sometimes I hear a robin in it, or a seagull, or a sparrow.’ We made a game of determining who would like a certain painting or drawing. Ed took for granted that my mother would be given something nice. We chose a female torso that was also an ascending spirit, drawn with light instead of shadow.

We kept ourselves going with tea poured into Ed’s spongeware mugs and with a lemon Bundt cake whose recipe he was perfecting, marrying bright tartness to decadent blandness. He told me he wrote to my mother for advice about mixing – he was getting little balls instead of smooth batter. She said the liquid and dry ingredients should be incorporated into the creamed butter in smaller amounts. Even when Ed and I were not speaking, he talked to my mother and she sent him food. He did not want to lose her – ‘the perfected version of you,’ he once observed. The blue-and-white mugs called forth a certain intensity. One horrid day Ed carted them off along with the years we spent together. He was not going to break up his current household, where Daniel would continue to live.

Joy Ascending Figure Study #1, 1991

I own many things that Ed and I bought together or made when we were a couple. I sleep in the cedar bed we built in 1975 when we moved to Clipper Street. Our sperm hit the headboard, a plain of roiling grain. When we broke up three years later, neither of us relinquished the bedroom so Ed made a pallet on the floor and there we were, sharing our unconscious hours yet too angry to speak or touch, except once – as if we made the jolting discovery of the other’s body. Ed whispered in a rush of caresses, ‘It’s a body to fuck and suck.’ My body was on the market. In 1978 muscles were requisite, in 1970 none were required. Then we lay together, drifting into bitter thoughts, the connection, that had overwhelmed before, becoming arbitrary.

I’ve slept in our bed for forty-seven years; it will be my deathbed if I’m lucky. Late-medieval meets Danish modern, my taste for grandeur curtailed by our lack of power tools. You climb into it: the mattress rides almost three feet above the floor. I wanted to give it a roof like the bed in Bosch’s Death and the Miser. Ed vetoed that, but we made a headboard so high that on either side an angel and a devil already haggle over the mourant’s soul.

When Ed’s possessions were distributed in February 1994, my own belongings gained potential energy. I could see that everything I owned was ready to travel, to desert. The healthy and the dying don’t have the same relation to objects, and I inherited Ed’s feelings along with his goods. My white Pyrex cup from 1953 will outlive me, visible on the sill, throbbing between world and nothingness. It came to me from beyond someone’s grave. I could see it for what it was. My books came from a corpse’s library; my own library will fill alien shelves. My tables and chairs – stripped of their aura of choice and intimate touch – arrived from dead people’s living rooms. Someone will take my white glass cup for granted until the knowledge of death returns.

One day in July 1994, five months after Ed died, Elin, Daniel and I faced the hopeless task of putting twenty-four years of art into useful order. Just as I grapple with twenty years of notes for this book! For decades I moved fragments from one journal page to another – pieces of Ed’s life and my own experience, decaying haystacks in the computer, events without dialogue, codes breaking down and formats degrading from one platform to the next, scraps spindling on my desk and in my head, gestures that yellow and fall from the branch. Some notes became illegible and others were legible but their context dropped away. I try stitching these decaying rags together – Ed’s suffering and my insufficiency – but tension and resentment put me to sleep. Tension: I want to be a good girl but how can I pick up clues without smudging the crime scene with my dirty fingers? That is, truth may exist, but it is stronger away from me. Resentment: yes. Why must love prove each time that it exists on its own without contingencies?

Repose Study #6, 1991

At first sight Ed’s studio was ordered to the point of tranquility: clean surfaces, potted plants, and objects isolated by the pressure of placement. Daniel and I stood back, mirrored irresolution. Elin plunged in, dividing our project into tasks. Elin is a small woman, tender and bold, with heavy dark curls and tremendous forward momentum. We looked at the slides – thank God they were dated – and arranged them chronologically in slide sheets of Ed’s various series: his clouds and vapor, his ascending heroes, his fish-bone watercolors, his fishbone sculptures, his ghosts and samurai helmets, his dividing cells, his flower drawings, his suite of illustrations for a children’s book about dying. The next step was to make duplicate sheets – but to what end? Over these activities arched the memory of Ed’s corpse, helpless, arms and legs akimbo. His lack of presence in his body made grief happen but I can’t explain why. It has something to do with the awareness of time, and something to do with my being human after all.

In Ed’s studio, my own life passed before my eyes. I modeled for Ed in the seventies, so I reviewed the generalized beauty of my young self. My long white face and caved-in posture, my skinny larval body under loose denim and flannel. Those years seem distant because they fly away inside me. And there was Gus in 1974, sucking me in drawings for a new gay magazine. What was it called? – after a few breaths it expired. So many journals died in the crib! Gus, editor-publisher, went to the mat for his publication. He was a stocky Italian with a jovial tooth fetish. He was more attracted to Ed’s small translucent teeth than to my robust corrected dentition, which made me wildly jealous for ten minutes. After our sweaty but matter-of-fact afternoon on and off a foam mattress on the floor of Ed’s studio under Ed’s eye, Gus paid for my time by taking me to a double feature at the Castro. He had obtained free passes as a citizen of the fourth estate.

How easy it is to put myself in his apartment after the forgotten films. In most homes, the thrift store and garage sale ruled, but Gus’s apartment was decorated in French provincial, generic as a hotel lobby or grandmother’s parlor, complete with clear plastic seat covers. The coherence of his environment felt weird. Was it rented furnished? – or rented furniture? Gus sat forward on the gold brocade settee and asked me to piss in his mouth. Actually I don’t recall the upholstery, but I do remember that my horizon of pleasure broadened right then. The plastic cover was sensible. It took concentration to remain soft enough to piss while inside. After finishing, Gus leaned back against the gold fleurs-de-lis and said mildly from the depth of his barrel chest, ‘I want to kill myself.’ It was two a.m. – bars were closing across the city. Fatigue is a speedy drug. Gus’s nameless roommate entered with a trick and we all piled onto Nameless’s bed. Gus blew the trick while I rubbed against the roommate. He had a haggard, acne-scarred face and a superhero torso with as little character as the furniture. His features were so big that I saw a Claymation cyclops when I climbed aboard. I was unpleasantly aroused. I wondered how he came by such an unusual body – it seemed to belong to someone else. That he’d attained it through exertion in a gym never crossed my mind. It was three or four in the morning in the early seventies and clobbering my body with five or six orgasms was a more familiar diligence.

Untitled, 1975

Ed dreamed that a man in briefs moved in geometric poses across the sky, watched by a wondering face – which Ed emulated in his sex and art, somersaulting through the vault. Bodies sailed through gleaming clouds, heroically foreshortened. Are they the clouds personified, or rather eroticized? If I assemble the paintings like the frames of a movie, the god shrinks and drifts off the edge and the clouds retain his essence. Flesh falls away and what remains is arousal in mineral heaven. They were experiments in empty space and arousal.

I am describing art that Ed made in our second apartment, the railroad flat on Sixteenth Street between Dolores and Church, where we moved in 1971. Ed turned the south-facing front parlor into his studio. I took over the living room by constructing the People’s Wall out of cardboard. We slept in the back parlor and conducted social life in the spacious kitchen. We painted it bright avocado and pale lavender – I smile to remember – and it held a sofa covered by a blue chenille spread. A sofa in the kitchen was great. We were surrounded on four sides, mostly by an extended Puerto Rican family. A continuous slab of rundown three-story buildings circled the block. Half-toppled barns from the nineteenth century decomposed in the open rectangle of weedy backyards and at dawn a rooster crowed. On the drab treeless street, we collected glass from shattered car windows for Ed’s sculptures. They were wall pieces, fish bones and glass suspended in polyurethane. Sometimes he covered them with Mylar scales. One horrid night in the dim garage we tried to extract bones by dumping dead fish into a plastic bucket of Drano – a vat of seething gore. Then the hot toxic sludge melted the plastic . . .

Daniel found a batch of resumes in a drawer and we used them to find and record which pieces had been sold or given away, to cross-check the pieces that remained in Ed’s studio, and finally to determine which still needed a slide. A small page from a magazine dropped out of a stack of drawings: a man has lowered his red bikini briefs, his dick sticks out like a lever, foolish, as though his body is switched on. A seventies body, a skinny blow-dried blond. We looked at him without comment; he disturbed me because our task was so boring. I wondered if Elin found him arousing.

Order and disorder. If I knew why Ed left his art in disarray and left precise instructions for his memorial service down to recipes for the buffet, I would know something more about Ed. Elin found a silver earring in a clear plastic box in a drawer. ‘Where’s the mate?’ – Daniel found it in a tray by the window. Here is a box of crayons, except for gray, green and magenta. They’re in a bowl across the room. What did this combination of order and chaos mean? The serene surface, the welter below? What can you do with the unruly scrawl of a person’s life?

Here’s a note from the pile – did Ed bequeath his share of this event? One afternoon I returned home, and Ed’s door was closed in such a way as to suggest he was with someone and they were naked, and sure enough I could hear gasps and sighs. I crept to my room, the cardboard wall and curtain-door, and sat disconcerted till naked Ed appeared and without saying a word organized me back down the hall. ‘Hi,’ I said to the skinny blond whose name I don’t remember, and I put my mouth on his skinny cock with its flange of a head. Tie-dyed curtains filtered light from the bay window. I felt nothing for him: I went to his flat on Prosper Street two or three times, just, Hi, hey, oh oh, spurt spurt, bye. Anyway he was more interested in Ed. His cock had two mouths and his sperm sort of dribbled. Who was he? Sandy and white, monotone and blasé, orgasms didn’t excite him. He had a lover, I now recall.

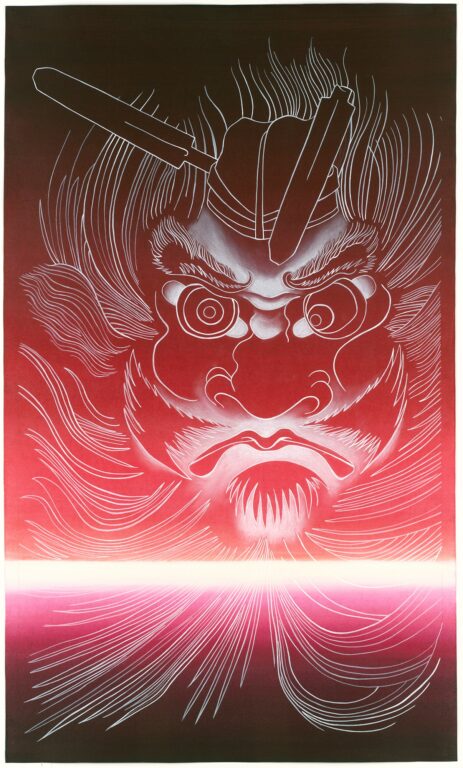

Shoki, The Demon Queller, 1989

Daniel, Elin and I arrived at a master slide sheet. We wanted to make an archive and place Ed’s work in galleries and museums. The lack of Ed’s presence in his corpse affected a part of me that I had never encountered, caused grief that I can’t explain. It didn’t affect my speech, which carried on. The past is no longer behind me but in front. My notes don’t collect insight and drama – what someone said, how someone moved. Instead of composition, I copy them insanely from notebook to notebook to computer, where they replicate through many files. Why shouldn’t they continue as shards hurtling away from each other like the big bang, if that’s how Ed exists for me? Or like Don Bachardy’s death drawings of Christopher Isherwood, where the empty space conveys dissolution?

Elin showed Daniel that the plants were stressed from lack of water, then she watered them. Elin had been part of our hippie family – she’d throw an overcoat over her nightgown, drive across town with Eli, her dog, jump into bed with Ed and me, and watch old films. Ed and I were not a counterculture success story – Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith. We never doubted that Ed was an artist, yet he worked alone. Often I was the world – how could I be? Perhaps his lack of success was due to an inability to prolong his forays into the art scene or even the world. He emerged every few years with new work; we carried it to galleries, to an art market remote as a mandarin’s inner court. I still want him to be recognized – for justice to be done. Ed’s grandest moment occurred in 1991, when he represented San Francisco for Day Without Art. His paintings of samurai helmets based on Japanese woodblocks hung in the Asian Art Museum – they looked great. He’d added his mother’s maiden name, Sugai, as he focused on the Japanese part of his life. It seems Ed Aulerich-Sugai dealt with sexuality when we lived together, in the seventies, and with race in the eighties. Mayor Art Agnos congratulated Ed and gave him an antique geisha doll, a gift to Agnos from Kyoto, but the museum didn’t buy a piece from the show. Was a sick artist a bad investment?

Catalogs from cheesy outlets like Ah Men and pages ripped from porn mags were tucked into bankbooks, journals, sketchbooks, among resumes, correspondence and income tax forms. Arousal refracted through every activity. Thongs projected genitals up and out in see-through mesh, Day-Glo Pucci polyester, and chaste white cotton. Bikini briefs dominated. Sometimes a photo conveyed an idea by the way a cock was shaded, held, framed: that a cock can be all reality till it comes. What did Elin make of these Donny Osmonds with boners? Gaggles of hard-ons can look silly and I felt gender embarrassment. Elin and Daniel didn’t seem to notice, which heightened my unease. Daniel and I – why not say it? – look alike, soft Jews. Meanwhile Donny duplicated himself a hundred times in Ed’s studio, where he kept his imagination, his dreams, his unconscious. Did Ed want Donny? How did he end up with two fuzzy Jews? – two Jews to care for him endlessly and to uphold his beauty? Did he feel Donny was too good for him? – or was he always fucking Donny anyway?

We were drinking tea from the blue-and-white spongeware mugs that Ed brought back from West Virginia. I told Elin and Daniel about it: in 1975, Jock, a much older man, a designer, took Ed to Huntington to work in a Holiday Inn. Ed painted a vast mural in the banquet hall: the Ohio River flowing through the seasons. Before Ed left, he carefully let our friend Stanley know that he did not want me to be lonely, propelling Stanley and me into an affair. It seemed logical because Ed had a fling with Cliff, Stanley’s boyfriend, not long before. Ed was not attracted to Jock (gray sperm) and Jock was passionately in love. I scolded, ‘If you’re selling yourself, at least make your customer happy sometimes.’ Ed confided that he cheated on Jock with other men. I was making Daniel uncomfortable. Their project went on for months – at one point Jock tried to push Ed off a bridge. What edge did Ed push Jock over? That Halloween our friends observed, ‘You’re going as Ed.’ His tight orange cords and sheer black shirt displayed a body ready for pleasure. From his vast collection, I chose white bikini briefs that launched my cock and balls. After we separated I took Ed’s qualities into myself. A movement of his head, the patience to play with Reese forever. Using his measure, not my measure. And after he died? My hero: fragile, heedless, elegant, determined, bonded to home, masturbatory, dreaming, thinking optically: ‘The fog drifts quickly. When I let the image fall from the center of my eye, I can’t tell the changing gray from the blue – the moving edge, white to blue, a screen of intricate white veins intermingling with soft veins of blue.’ Then I am Ed.

The day took forever, but a day is not so long to inventory a life and by the end there it was: Ed’s life, with its shape and no other. I can’t complete the inventory of what he carried into death.

I sat on the edge of my cedar bed. It supported so many moments of fullness and emptiness that started with Ed and continue in the present. It has four big drawers and a cabinet, and a hidden compartment where I keep boxes and portfolios of art. The mattress is a Cadillac because Carl had a bad back. The sheets are . . . I just wanted to sit for a while in the decaying light. I was glad for a moment of emptiness, aspired to it. Led myself to it. Stopped disguising myself from myself with the aid of the emptiness Ed loosed on me, and it’s here now, as though he’d rendered me with negative space.

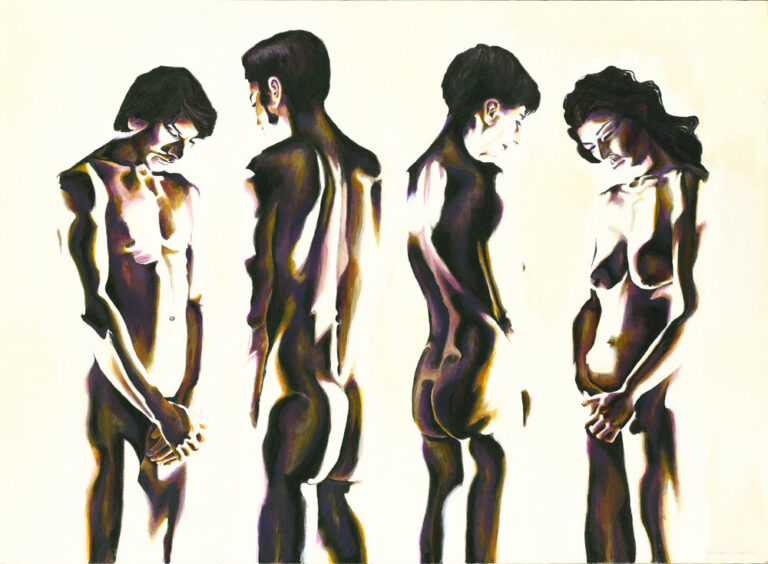

Figures, 1991

I lay down, arms crossed behind my head. Ed’s voice on the phone: it seemed to come from inside me, but that didn’t mean I was always glad to hear it. I half listened to his dire sagas – the brutality of one doctor, the indifference of another, nausea caused by a drug or perhaps a different drug. There may be a place where actions are full, where feeling meets event, but I was not there. A slice of Clipper Street through the blinds, my white cup on the sill, the neighbor’s dog barking hoarsely below. Arf. Arf. Arf. Death was partly a shrug and partly uncontrolled grief. I lived with my generation so I was not looking for the meaning of life, which was obvious: life is the fulfillment of itself. We accepted the infinite – the expanding universe, the World Wide Web, the national debt. The finite had become mysterious, illusive. The opposite of physics, each new version was more disunited. I couldn’t find life, as though I’d lost my feelings with my glasses in the folds of the blanket. It struck me that I was somehow responsible for Ed’s death. That was consoling. Worse was the thought that it had nothing to do with me.

Then sadness gripped me as though it were fear – wild, focused and cold. I couldn’t catch my breath I felt a weird buildup: to die is to disobey a rule. I needed to cry for Ed, who could no longer care for himself or obey rules. I began to cry, or rather howl, a sound I’d never heard before. My body could not arch enough to meet the demand. A hook in my throat dragged me through salt water. Sickening tears, because the shape of Ed’s life had become apparent. This flat for now, this city for now, this job for now, these friends for now, this lover for now, this art for now – in one stroke he became the life he lived, the irreversible shape. I couldn’t change it. Going through twenty-five years of Ed’s art, so full of hope, I was filled with Ed yet there was no Ed. I could only express his presence and absence with cries and shouts. I had never known tears so entirely linked to an event. My ribs hurt, I could not arch enough to wriggle off the hook. I didn’t cry over his corpse, but over the body of his art. I thought, Oh please Ed, I don’t want to be in this. What did I mean? I was bursting with Ed – my head rolled as the top of it exploded and my eyes went back. I felt the vibrations of a boxcar moving in the darkness. The dust cleared but there was nothing left, a loss of density. I went beyond self-protection. I became the image on a strip of film – that’s how I can explain it – slipping into two dimensions, a photographic negative lit for an instant and then curling downward into darkness. As though I were falling into darkness down a slot. I lay in bed with that pressure behind my eyes and hot skin. Ed had no more life but also no more death. The pain in my chest still blared, a feeling of expectation.

My tears were a starting point. That would be true of any outburst so purely physical. Time began again with a difference. Emotion found its story. I experienced that justice. From threadbare material – Ed, sickness, myself – a full-fledged sorrow had emerged, weirdly impersonal, below my shame, not regardful, gathering strength till I barked out grief like a dog. At least this sorrow could not be assessed, found incomplete. Or did Ed’s death allow me to feel what was there all along? We were typical, one who dies and one who escapes infection. I had thought I was surviving Ed. Now in the pathless night I was waiting to join him. It’s not something I believe, not something he believed, yet the words convey a feeling. I was not ready to die, though I’d considered it. I was not too young to die, and for centuries I had been trapped in a grueling conversation that only death could interrupt.

I turned over and over to find the position that led to sleep, but consciousness roused itself in defense when sleep approached. I could not draw into myself. Maybe it was a problem of expression: I needed to find a language for Ed’s death. My eyes turning away meant the sight of a corpse. My head falling backward meant the empty body. Covering my face meant grief was contained. Arms raised as an urn meant showing ashes to the sky, meant readiness and openness to the sky, and film spooling into darkness – what was that? I pushed down a frantic feeling. Dawn, pale gray. I could not lose myself until I remembered to unclench my fist and lay my hand flat against the sheet as though absorbing the horizontal. I spread my palm as though registering my identity, then pressed against the door. My breathing grew regular and waves of sleep carried me through.

I woke to a half sleep. I was not dreaming, but remembering my dreams, paging through them: I suck Kathy’s cock in the front seat of my car. Before that, my family and friends have Thanksgiving dinner – surprise! The surprise is that I’m not invited. Mom and Dad are clowns in whiteface. Mom doesn’t have a mouth and I sort of run out before nothing is said. Before that, Chris and I are returning home late – I had to miss the episode on TV where Ed and I – what? Our life is a situation comedy. I want to see the rerun. When we break up? Go to Mexico? Make sushi? The fish and Drano? Chris and I pull into the weedy driveway and there’s Ed! I’m slightly confused. ‘Aren’t you dead?’ Then I allow myself the joy of seeing him. He’s relaxed, lanky, glad to see us. He kisses Chris and then comes to kiss me but he is thrown to the side. He looks winded and his eyes widen as he’s thrown backward and disappears.

I opened my eyes to see where I was. My senses began with nothing, with consciousness you might say, dissected into birdsong, cool air, an insect bite, hunger, stale flavor, expectation, floaters drifting downward, the foreshortened hairy body, a strange body whereas its inner tingling was myself. I tried to get up, rich sleep, thick feeling, then fell to marveling, I was so comfortable. ‘I love this city,’ etc.

Artwork courtesy of the estate of Daniel R Ostrow, custodian of the Ed Aulerich-Sugai Collection and Archive