We brought rings and two witnesses to the Edenvale Home Affairs office because we had been told to.

It was 22 February 2009. I had gone to the office, located on a scrappy strip of motor-repair shops and panel beaters east of Johannesburg, to book our ceremony three weeks previously. My partner, C, and I had been together for nearly two decades, but we had little interest in the rites of marriage. We had decided to do it, now, solely because it would facilitate our move to France, where he had been offered a job. It was, we told each other, merely an administrative matter.

Three years before, the South African parliament had passed a law permitting same-sex marriage, upon injunction from the Constitutional Court. We could have done it more easily – through a gay rabbi I know, for example, or a gay judge who is a friend – but we wanted to see the system work for us. Even though we lived on the other side of town, we chose Edenvale because friends had had a positive experience there. Like all Home Affairs offices, it was grimy and arcane, contemptuous and chaotic; the last place on earth you would want to get married. In the old days, Home Affairs had been the processing room of apartheid: it told you who you were and where you could (and could not) be. It was still a place of profound alienation; of a million frustrations and rages a day.

And I was about to have one of them: I had been waiting in the queue since 2.30 p.m., and had only made it to the front just after 3 p.m. Although the office closed at half past three, processing stopped half an hour before, and I was just too late. I would have to come back the next day. I was on the brink of a spirited lecture on the meaning of ‘Batho Pele’, the department’s new slogan of ‘People First’, when one of the women behind the desk looked up at me, gold hoops in her ears to match her attitude, and barked: ‘Same sex or opposite sex?’

It took me a moment to comprehend. ‘Same sex,’ I said, a little too loudly, glancing round to see if any of the other clerks in the room would look up in shock, or perhaps just interest. They did not.

‘The marriage officer likes to do the same-sexes early in the morning,’ the woman said briskly, consulting her book. ‘Too much paperwork, you people. You’ve made our lives much more difficult.’

Before I could protest, the woman shoved a form across to me, noting the time and date of our appointment. Pulling out a green highlighter, she underlined a reminder that at least two witnesses were required. ‘We have room for twenty,’ she said, ‘so bring all your friends and family.’

‘No, no,’ I protested. ‘It’ll be just two. We don’t want to make a fuss.’

‘Why not?’

When I shrugged and spluttered an answer (‘purely an administrative matter’), she looked at me severely. ‘A marriage is a big deal. Make a fuss. Don’t forget the rings.’

We would not be doing rings.

‘Why not?’ she repeated, before answering her own question: ‘Ah, you don’t want to make a fuss!’ And then, in counselling mode: ‘Do you think you are a second-class citizen just because you are gay? You have full rights in this new South Africa. You have the right to make a fuss. I think you need to go home, and have a very serious chat with your partner. We will see you at 8.30 a.m. on 22 February. With witnesses and rings. Goodbye.’

There I was, an entirely empowered middle-class, middle-aged white man, being lectured by a young black woman about my rights. And here we were three weeks later, with rings but, alas, only two witnesses, being ushered up the stairs by a delightful security guard who told our friend that she was a beautiful bride but who shifted the compliment effortlessly to me when corrected.

We found ourselves in ‘Room 8: Marriages’ at the back of the building, overlooking a scrapyard next door. It was a parallel universe: the room was draped in lace of the same dead colour palette as the dried wild flowers set in vases between white porcelain swans. There were wedding photos of various couples tacked on to the walls and, on every available surface, cascades of what turned out, on closer inspection, to be empty ring boxes. It was inexplicable at first, then comical, then unexpectedly moving.

‘You like it?’ trilled a voice behind us. A middle-aged Afrikaans woman had entered. She introduced herself as Mrs Austin; she was actually in finance, but she loved marrying people so much that she had applied for a licence and now did it two mornings a week. ‘This is all my work,’ she said of Room 8, explaining that every couple she married was invited to leave its ring boxes behind, and that among these boxes were ‘same-sex’ ones: she was proud of the fact that she had married more gay couples than any other officer in the province.

Mrs Austin made no secret of her disappointment at our lack of campery: where were the feathers, the champagne? After some jocularity over who would be the ‘man’ by signing the register first, she led us through an unmemorably bureaucratic script ending in ‘I do’ and a kiss before presiding over what was clearly, for her, the more significant part of the proceedings: the swapping of the rings. I slipped on to C’s finger a delicate band of red gold fretted in the South Indian style of his ancestors, while he wound on to mine a thick chunk of silver. Exhaling approval, Mrs Austin extracted a red heart-shaped ring box from her installation and balanced it between our two hands, which she delicately arranged for a photograph. We spent more time on this ritual than we had on the actual ceremony, and as we posed I admired the contrasting styles of our rings and what they said about our relationship.

It was, in the end, the lack of moment to it all – the unportentousness, if there is such a word – which finally moved me. Even though Mrs Austin kept referring to us as ‘same-sex’, and heterosexuals as ‘normal’, we were swept out of Room 8 on a tide of hilarity and giggled all the way to breakfast. Even the fact that she could not furnish us with a marriage certificate – the computers had been down for six weeks because someone had stolen the cables – did not dampen the good feelings. We were a white man and a black man, free to be together in the country of our birth, treated with dignity and humanity and much good-natured humour by a system that had denied both for so long.

I am forty-six and C is fifty. We live our lives openly; our families and colleagues and neighbours all know that we are gay and together. It is his choice, however, to be private; to remain outside of my public identity. As we drove away I felt, for the first time, what it meant to claim a right once denied, to claim the freedom to choose: the bounds of our privacy, the terms of our public engagement. Well worth the fuss.

On the day of our marriage my father was recovering from surgery. We went from breakfast straight to the Sunninghill Hospital to show him and my mother the rings before going off for a night at a country hotel. Despite my father’s condition and over our protestations, they insisted that they would throw us a wedding party, just as they had done for my brothers. A few weeks later, we invited a few people around to their home: although my father was very ill, he played the host with his trademark bonhomie and gave a characteristically well-wrought speech, brimming with love and cut with emotion. It was his last public act; he was back in hospital shortly afterwards and died three weeks later.

I write this now, from Paris, around the time of the first anniversary of our wedding and my father’s death. C never takes his ring off; mine sits in a bowl on my desk amid the flotsam of a work-at-home life. I often fish it out and fiddle with it while I work, as I am doing right now; I screw it on and off, I flick it into goalposts made of books, I tap it against the teapot. I weigh it in my palm and am impressed, each time anew, with its heft. When I rub it, I conjure the empty rows of chairs at Mrs Austin’s chapel on the day we were married and I fill them with family and friends, with characters fictional and historical, with all the people we might have invited to witness our union had we succumbed to one of the more conventional affairs that grace our respective families’ photo albums.

My father is always there, at Edenvale, alongside my mother, as are C’s parents, who died before I met him. So too are two older men, Edgar and Phil, whom I have interviewed several times during the past decade. It would be presumptuous to call these men fathers, or mentors, or even friends; we did not, for example, invite them to the farewell party we held shortly after our marriage and at which we revealed to our astonished friends that we had eloped. But such is the pleasure of an empty chapel: you can fill it retrospectively, endlessly, variously, and I often find Edgar and Phil there, sitting on those grey office chairs amid the ring boxes and the swans.*

II

Edgar had two wedding rings, he told me. He wore one on his left hand and the other around his neck.

The first was a solid gold signet, conjuring the respectability of a Soweto patriarch: his marriage of over fifty years; his decent clerical job; his home shared with his wife and fifteen of his progeny – children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

The second was a lush red silk tie, given to him by a male lover, since deceased. His family might have seen it as another item in his snappy wardrobe but he wore it with purpose, to commemorate the man. ‘He worked for Liberty Life and he treated me so well. He was amazing! We would go places. It’s still there, the tie. It’s red, beautiful. I love that tie!’ Edgar spoke with characteristic ebullience before anxiety overcame him: ‘But at times it is painful when you have a friend who is not faithful . . .’

You could see the complexity of his situation wash across his broad, handsome features. He shimmered, in that way of some older people: there was a glint to his smile to go with the liver spots on his cheeks and the clouds in his eyes. ‘You’d be sleeping next to your wife for six months and you’re not having sex . . . I would advise anybody to honour their relationship and to be honest, because otherwise it kills you, spiritually and otherwise. Even at work your concentration is divided. In the life I have lived, you should have a room for disappointment.’

In my middle-class life I have always had a room: for sex, for love, for rest, for reading and writing, and – of course – for disappointment. Edgar had to make his rooms where he could find them.

Their wedding bands were the first things I noticed when I met Edgar and his friend Phil in 1998, at a Soweto tavern named Scotch’s Place. While Edgar wore the conventional choice for a man of his generation and class, Phil’s ring was groovy and geometric, with a sportif ‘S’ carved into the gold. Both rings were assertive and masculine, planed rather than curved, and spoke of the substance and solidity of their wearers. Phil, like Edgar, was a married grandfather; he owned a home in a middle-class part of Soweto and drove a car; he was approaching retirement from his own clerical job at a commercial company in town.

These were the days when a wedding ring still meant you were straight, or in the closet. And so Edgar and Phil’s fingers flashed a particular code as the men sat in the semi-obscurity of Scotch’s interior, having chosen a table that put them in the direct flight path between the doors to the yard and the bar. As patrons streamed in and out, Phil or Edgar would mutter something sotto voce, and a young man or two would linger for a moment, engage in conversation, and maybe sit down. By the time I left three hours later, chairs had been pulled up all around them and tables pulled together. All these young men had impossibly waspy waists with button-down shirts neatly tucked into smartly pressed jeans, or tank tops riding well above the navel: ‘amaphophodlwana’, Edgar and Phil called them, using isingqum-ngqum, the township gay slang, derived from Zulu migrant labourers; ‘small boys’. A friend later explained that in regular township slang, the word was used to describe a frisky young animal, a kid or a puppy.

I noticed, at Scotch’s, that Edgar and Phil never went outside to the yard, where most of the amaphophodlwana gathered. This was not the 1970s, when you could more easily be an ‘After-Nine’: go to a tavern after work under the pretence of just having a drink, and allow your gayness to show ‘after nine’ once all the straight men had gone home to their families or were too drunk anyway to notice what was going on. No: this was the late 1990s. Same-sex marriage was still a decade off but the constitution had outlawed discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, and a gay youth scene was budding in Soweto. Places like Scotch’s were openly gay, literally: the yard gave way to the street, where patrons gathered around cars blaring music, as if at any township street bash.

‘Look at them,’ Phil said, with desire and disapproval. ‘We were not as free as they are today. Today they are very free. Very showy. You can see them miles away. I won’t go around with a boy in a skinny top and a belly button outside, no. No, no, no, no.’

Edgar and Phil themselves dressed with conservative style – sharp shoes, crisply ironed slacks, Pringle shirts, fine watches. Phil was diminutive and light-skinned, wiry and twinkly, with a neatly trimmed peppercorn beard and expressively creased crescent-shaped eyes that suggested traces of Khoisan – or ‘Hottentot’ – blood. He had a stammer that might have been exacerbated by age but was nonetheless full of gentle mischief and occasionally blunt lasciviousness, and had a quiet charisma that seemed to attract the clientele at Scotch’s. He was known as ‘Mr Soweto’ in his circle, and always had a trail of young men after him. ‘You and your beautiful-ugly face!’ laughed Edgar.

Edgar himself was tall, dark and well built – ‘a typical Zulu man’, Phil riposted playfully, pinching him in the side. He had the easy, straightforward confidence of a matinee idol or the lay preacher that he was: his shirt collar was opened to a gold chain, and he was given to exuberant laughter and emphatic stress. The two men bantered gently with each other, their intimacy suggesting that they might be old and comfortable lovers, which is how many saw them, although neither used this term to describe the other. Their friend Roger – a white man who introduced them to me and who has known them both for forty years – believes that in another life, a free life, they might have made a home together.

At Scotch’s, they disagreed about when and how they met: Edgar was sure it was at a neighbour’s home, shortly after they had both married and become fathers in the late 1960s. Phil was equally certain that it had been in the early 1970s, after he had given Edgar a lift home from Lee’s Place, another tavern where gay men would gather ‘after nine’.

‘We clicked immediately,’ Edgar said, as Phil nodded affirmation. ‘We started going to social functions together. Fishing was our thing!’ The word was Edgar’s own, idiosyncratic rather than subcultural, but it describes beautifully that part of their lives spent together, as men away from their wives and families, engaged in the pursuit of illicit, underground intimacy.

Phil later elaborated: ‘We shared more than a friend [does], but not as lovers. We shared the problems in marriages and the problems with lovers. If you just have a sex partner, no problems. But if you have a lover, someone you’re going to miss, someone you’re going to die to be with, then you have problems. You make an appointment, he doesn’t come. Next day, he doesn’t come. You need to speak to someone. That’s when you’d go to Edgar.’

‘Or you’d come to Edgar because I had a phophodlwana you want,’ Edgar responded.

‘See what I told you,’ Phil addressed himself to me. ‘Typical Zulu man.’

‘Yes,’ Edgar shot back with affected pride – ‘Typical Zulu Man’ – before launching into the story of how his life only started at the age of eight in rural Zululand, when he became old enough to start cattle-herding: ‘Inbetween herding cows, we boys would go for a swim. And that’s where I started appreciating boys – swimming in the Mvoti River!’ At the river, Edgar engaged in what was known as hlobongo, the traditional Nguni practice of non-penetrative sex used to channel the libidinal energies of boys before marriage. Generally, you did it with girls, but it was perfectly acceptable to do it with boys too – particularly among Zulus, where the great King Shaka had encouraged the practice among his male soldiers. As Edgar put it: ‘Men would just be on their own for a decade, in battlefields and what have you, and they would do this, and I tell you, it’s a beautiful experience to have a man with you. Zulus do it professionally!’

He turned to his friend with the air of challenge. ‘Am I not right, Phil?’

‘You are right . . .’

‘Professionally! Although they would deny it in the presence of other people . . .’

‘You are not denying it tonight, my dear.’

In 1944, when Edgar was ten and the South African economy was booming due to the war, his father found a job in Johannesburg and moved his family up from Zululand. They settled in Pimville, the ‘native settlement’ south-west of Johannesburg that would become the germ of Soweto. The focus of Edgar’s Pimville youth was the Klip River, which ran through the township: here he joined other boys in recreating their traditional age-mate groups after school. They prodded the few scrawny goats and cows about; they swam; they fought with sticks; and they found each other’s thighs.

Like many Soweto women, Edgar’s mother took in washing for white households in Johannesburg. And Edgar, like many Soweto sons, would be sent into town to collect the laundry and then drop it off when done. And so – as happens with boys all over the world when they discover trains and the cities they lead to – his life changed: having delivered the goods, he would go ‘fishing’ in Joubert Park or at Park Station on his way back to the township. ‘I was sixteen,’ he had told me, ‘a Zulu boy. Hefty! Plumpy! I wore shorts, very tight shorts! I was a fit young boy; men of all races would be attracted to me.’

Phil also grew up in Pimville; his father, a farm labourer, had come to town and found work during the wartime boom. Phil did not know Edgar as a boy – he went to the state high school rather than the mission school Edgar attended – but he also discovered his sexuality through washerwoman subterfuge. While still a schoolboy, he was working part-time at the fresh market on Saturdays. A customer, a young white man, struck up a conversation with him as he was carrying a sack of potatoes to the man’s car. Having ascertained that Phil’s mother took washing, the man proposed that she do some work for him – and that Phil collect it the following Tuesday afternoon. When he duly arrived, at a swish flat in Jeppe Street, he was greeted by a man with no clothes on. Phil let out a long, dramatic sigh as he relived the experience. ‘Was-I-shocked! I just looked, and looked. I had known there was something amiss with me, but I couldn’t put a finger on it . . .’ The man apologized for his nudity – all his underwear was in the laundry pile – and approached, tumescent, beseeching his visitor not to be afraid. ‘Oh, I nearly fainted, and the next thing I knew, my trousers were pulled down . . . From that day I knew all along that I wanted a boy in my life. That was the thing I had wanted all along . . .’

Phil dropped out of school, much to the fury of his ambitious parents. ‘I was too streetwise,’ he explained to me. ‘I liked the money. It was my chance of meeting men.’ One of Phil’s favourite haunts was the Union Grounds, at Joubert Park, where white soldiers were barracked after the war. ‘He is on one side of the fence and you are on the other. He pulls down his pants, and puts his whatsisname through the fence, and you put your hands through the fence and get hold of him, and you do your thing. There and then. And he gives you two and sixpence.’

‘Weren’t you worried?’ I asked.

‘About what?’

‘Being seen!’

‘The lights in those days were not as bright as the lights today,’ he deadpanned back.

Phil married for love. He met Mo on a train and fell for ‘her beautiful country smile’. She was on the way to the city to finish her teacher training. He carried her luggage for her from the station to her lodgings and kept an eye on her once she was there. Their courtship was urban and sophisticated, even in apartheid Johannesburg. On their first date he took her to the movies at Sophiatown’s famous Odin Cinema. This must have been in 1955, just months – or even weeks – before the bustling cosmopolitan district was demolished almost brick by brick and replaced by the white suburb of Triomf and its 65,000 inhabitants forcibly removed to Meadowlands, outside Soweto.

Such was Edgar’s love of men, on the other hand, that he paid no attention to the possibility of marriage until his parents died in 1957. By this point he had ‘fished’ his way through vocational school in Soweto, where he had studied carpentry, and his Pimville church, where he had become a lay preacher. After his father’s death he discovered that he would only be able to keep his meagre inheritance if he married. So he accepted the woman chosen for him by his relatives, and they quickly had a family; he gave up carpentry, and found the clerical job he would keep until retirement.

Now that Phil was married too, a neighbour found him a job as a messenger in town. His wits were such that he was soon promoted to a desk job. It did not take him long to understand, as he put it to me, that ‘you have to be rich to be gay’, not least because you had to support two parallel lives. ‘In married life you should be a responsible and trustworthy man,’ he told me. ‘That’s why I’m still in the closet.’

Phil and Edgar held much stock in being exemplary family men: to provide, to be home for dinner, to be sober. Gay men, Edgar had it, were particularly good at this. ‘The wife knows that you are responsible. She knows, at least, that you like to improve the house!’ This cut them the slack they needed to lead their complicated lives.

They also experienced, alongside the pleasures of fatherhood, the often unutterable pain of raising children in South Africa in the latter half of the twentieth century. Neither man could bring himself to talk about the loss of his son: Edgar’s to Aids and Phil’s to the liberation struggle.

They never discussed their sexuality with their wives but Phil still cringes with humiliation when he recalls how he was once caught out. He had borrowed a book from a friend on homosexuality, and his wife came upon him reading it. He spluttered an excuse – it was just something he had picked up – and when the book went missing he assumed she must have thrown it away. Unbeknown to Phil, she had actually read the book, and loaned it to several of her girlfriends so that they might better understand their own marital circumstances. I know this from the book’s owner, a younger black gay man, whom Mo once told: ‘I know what he is. I can deal with it. He’s a good man. And at least he is not running with other women. I’m not going to lose him.’ Such are the tragic silences in marriages that she was not, ever, able to say this to Phil himself.

Phil was torn, he told me, ‘between the love of my wife and the love of my “small boys”. Gay life and straight life are different things. The comfort you get from a partner is different from the comfort you get from your wife. A partner is more intimate than a straight wife.’ When I asked him to elaborate, his response was startlingly concrete: ‘In the African tradition, sucking is taboo. Licking one’s body, for a married woman, no. But with a gay boy, he can do whatever. He kisses you, he licks you, he sucks you, he does all the wonderful things. Once you have tasted a man, it’s not easy to forget.’

The last time Phil and I met, it was shortly after the polygamous South African president, Jacob Zuma, had been forced to concede that he had had a baby – his twentieth child – as the result of an extramarital affair with a young Soweto woman. Phil disapproved strongly of Zuma but had some sympathy with his situation: older men needed younger partners, male or female, to keep the lifeblood – the bloodlines – coursing. Like their fathers, Phil and Edgar were patriarchs, with scant regard for the intimate needs of their women. They too were polygamists; unlike their fathers, though, their second ‘wives’ – their second lives – were secret.

Phil once said to me, about his life: ‘To be black and gay, uh, uh, uh! It was double trouble.’ He explained: ‘Gay life in Johannesburg, it was very tough, especially among blacks because of the curfew, and your freedom and your privacy was the most important thing. With whites, I would say, it was much easier.’

The apartheid city was a place of manifest oppression. Even if they had lived there for two or three generations, black people were ‘temporary sojourners’ who had to leave by curfew if they were not barracked in servants’ quarters. Very few black men went through life without a visit to ‘Number Four’, the dreaded Old Fort Prison, on a pass offence.

And yet the city was also a place of possibility and even, paradoxically, liberation. You could lose yourself in the crowd, away from the prying eyes and constraints of your community; you could spend your money on something other than beer – the only commodity widely available in the township. I will never forget the bitter-sweet story an older black man once told me, about how exciting it was to strut down Eloff Street, buying clothing by pointing at what you wanted from outside the shop window: black people, obviously, could not try on white clothes. Never mind: you returned home on Saturday afternoon to the smoggy township – Soweto was only electrified in the late 1970s – with the proof of your urbanity in hand and you felt a man of the world.

Once Edgar and Phil came to the city – first on the washerwoman pretext, and then because of their jobs – they found a new level of freedom. Or perhaps, more accurately, they learned how to play a new game of cunning, taking advantage of the opportunities now available to them while avoiding the double jeopardy of being black and being gay.

You might meet another black man in a desperate tussle in a locked toilet stall at Park Station or through a furtive grope on the crowded train home, but if you wanted a bit of space and a bit of time – if you actually wanted to undress and caress – you needed to find a white man. This was not so easy. A whole raft of laws prevented black people and white people from doing anything other than working together – and even then, only if blacks were in menial jobs. The Immorality Act proscribed sex across the colour bar, and in 1964 alone, 155 couples were convicted of this crime. And of course, in this time of intense political repression (Nelson Mandela was arrested in 1962 and sentenced to life imprisonment in the Rivonia Trial in 1964), any interaction across the colour bar could be interpreted as subversive activity and land you in jail.

All through the 1950s and early 1960s, there were periodic crackdowns on homosexual activity in Johannesburg, particularly at Joubert Park, the city’s primary cruising ground. Both Edgar and Phil managed to avoid arrest but they know many men who did not. Phil recalls the humiliation visited upon two friends who were arrested in a sting – and were forced to shuffle along the pavement to the police van past commuters who could well have been their neighbours, with their pants around their ankles.

Once he was working in the city, Edgar found his way, during lunch hour, to Joubert Park. Here, he and other black men would linger on the post office steps waiting for white men to drive by and pick them up. This is how he met his first white lover. For five years, the man would collect him at lunchtime, take him to his flat in Malvern and get him back to work in time for the afternoon shift. ‘I accepted it. If it’s love, it’s love at its best. If it’s not, it’s not. I’ve always lived that way.’

Sometimes, the white men would invite them back on the weekend, for a party; here they would meet other black men – also married, also from the township. ‘You’d have to go through the tradesmen’s entrance,’ Phil told me, ‘or you’d be introduced to the watchman as someone bringing the washing. Or you’d pretend to be helping your friend by carrying a heavy thing into his flat, or delivering a loaf of bread.’

In this way Phil and Edgar found themselves frequently, over the years, at the home of their friend Roger, the white man who initially introduced me to both of them. ‘Our lives revolved around trying to get around the law, or beneath it,’ Roger told me, as we sat in the suburban Johannesburg home he shared with his long-term partner, a black man named Sello who – extraordinarily – lived in white Johannesburg with him and worked as a professional from the mid-1970s onwards: his Botswana passport afforded him the reviled ‘honourary white’ status that enabled him to live in the city.

Roger is intense, verbal, pallid and precise; he is always dressed in the pastel colours – mauve tie against lemon shirt – of a Madison Avenue executive. A good decade younger than Phil, whom he had met in 1962 while a student at Wits University through the small mixed-race scene that had clustered around the post office steps and then found its way upstairs to the apartments of two older gay men, one Austrian and the other German. After a brief fling, Roger and Phil became lifelong friends; through Phil, he later met Edgar.

Roger’s home is high up on one of the dramatic ridges north of the city, where he has transformed a rather ordinary 1930s bungalow into an Edwardian folly, with conservatories, statuaries and gazebos. He has also planted borders of soaring cypresses, entirely obstructing the home’s magnificent view over Johannesburg. This was deliberate, Roger said: he needed to make a refuge for himself and Sello, and for their friends.

‘Our intention was to make a welcoming atmosphere,’ he told me as we sat in his living room looking down on the formal gardens beneath, set out around a sundial, ‘a place where our black friends could meet us and each other safely and feel secure in the white part of town, particularly if it was after curfew.’ There were certain rules: the bath was always full, for example, so that you could wash off someone else’s bodily fluids if there was a raid, and the music and chatter was always kept low, so as not to attract attention.

Edgar became uncharacteristically dreamy when he talked about Roger’s garden. One might imagine how he felt, arriving there after having evaded his family-filled matchbox home, the incessant township noise, the sharp-elbowed train, the Eloff Street crush, the crime-filled streets, curfew gauntlets. ‘Sometimes I would just go there by myself, even if I did not have a boy, just to sit in that Garden of Eden and chat to Roger.’

The reference to not having a boy stems from the usual nature of the gatherings at Roger’s home and the homes of other white friends: they were about sex, and they were somewhat transactive. The white men would provide the space for their black friends and their partners to have sex freely and without shame or fear of disclosure; their black friends – Edgar and Phil, in particular – would trail a wake of amaphophodlwana to share with their hosts. It was never, however, explicitly about money and, it seems, neither side felt exploited.

Phil is emphatic, and characteristically straightforward about the benefits of lifelong friendship with Roger. As I sat with him, in March 2010, in his home – a solid-face brick suburban ranch house with a red-tiled roof that would not be out of place in a ‘white’ suburb like Randburg or Centurion – I asked him if being gay had opened up a broader world.

‘Oh, yes,’ he replied. ‘Yes, yes, yes, yes. I got in touch and I got wiser. If I wasn’t gay I wouldn’t be staying in a house like this.’

Was he suggesting that his white friends had paid for it? Not at all: his employer had been an early facilitator of mortgages for black people, and he had been one of the first homeowners in Soweto, over fifty years ago. He explained himself, with a sweep of a hand that took in the leather couches, the flokati rugs, the books, the babbling Italianate water feature and fish pond, the modish patio furniture around it: ‘This, all of this, I copied from the white friends I used to visit. Roger taught me a lot.’ Phil and his wife were also, frequently, Roger’s guests at business functions; Roger’s liberal younger colleagues would invite them home to their families, as a mark of their worldliness. ‘So I would go to their homes, see all these beautiful things, and I would say, “One day, I’ll have those things to myself. I’ll have a house like this.”’

One of the things Phil and Edgar shared, in contrast to their other black gay friends, was that neither was particularly interested in white men as sexual partners. Phil was blunt as ever about this: the only whites who were interested sexually in blacks were older men who could no longer attract young white men, and who thus sought ‘to console themselves with young black men. Me, on the other hand, I have to have a younger man, or I do not get an erection. Even now, so long as he is younger, I will get hard. This is why black men are for me!’

Phil has had four lovers in his life, he says; all black men from Soweto. The first three broke his heart. The fourth has been with him for the past four years. His name is J.B., he is twenty-three years old, he lives with his family in one of the squatter camps surrounding the township, and he works as a security foreman.

There were a couple of rare, treasured places where, during the years of apartheid, Phil and Edgar could relax among other black people in the city. One was the Non-European Dining Room at Park Station, set up by the government in the early 1960s to show the world that blacks really were ‘separate but equal’. It might have been an apartheid publicity exercise but it was also ‘the only place in town’ where black people were afforded the dignity of being able to ‘sit down and have a drink, and eat a meal’, Phil told me. Propaganda photographs show well-dressed black couples, or groups of businessmen, sitting at formally laid tables in an airy modernist interior of wood, light and geometric pattern, attended by liveried black waiters.

According to Phil and Edgar, most of these waiters were gay and a subculture quickly developed around them. Telling me this story, Phil slid into another, about female prostitutes, who also frequented the restaurant. They would be picked up by white johns outside the station, and when they went back to their clients’ homes they would make an arrangement with the manservant in the back room: if the house was raided, the working girl would rush into the ‘boy’s room’ and climb into bed with him, pretending she was his girlfriend. She might be charged with contravening pass regulations but at least she would evade the far more severe Immorality Act.

The reason Phil was telling me this story became clear as he continued. It was a story about curfew and what you did if you missed the last train. Instead of running to the station, where the police would be waiting to pile all the laggards into their vans and haul them off to Number Four, you would make your way to Peter’s place. Peter was a domestic worker who lived in a ‘boy’s room’ behind his employer’s house in posh Forest Town, just a couple of miles from the city centre, and from the way Phil tells it, you might indeed plan to miss the last train back to Soweto. ‘You’d get there and, oh brother, those were the days! His room would be full, so full of young men afraid to be roaming the streets at night.’ As was often the custom, Peter raised his bed on sandbags and bricks to protect him from dog-demons, ‘and he would make a bedding all around him for everyone coming in. I remember one time it was so full that you couldn’t open the door. I slept against the door but in the morning when I woke up I was next to the bed, maybe even under the bed, because those were the days, if you have got someone gay next to you, you’d enjoy yourself for all the dry months that you never had a gay person with you!’

I worked out with Phil that this experience would have taken place in 1966 – the same year a more infamous party in Forest Town was raided by the police on 21 January at 14 Wychwood Road, where nine men were arrested for ‘masquerading as women’ (a law passed initially to catch criminals in disguise, but used occasionally against drag queens). The headline in the Rand Daily Mail read ‘350 in mass sex orgy’; the raid provoked a massive public outcry, with the Minister of Justice stating during a parliamentary investigation that ‘we should not allow ourselves to be deceived into thinking that we may casually dispose of this viper in our midst by regarding it as innocent fun’.

This was South Africa’s Stonewall moment. The state then proposed legislation that would make it illegal to be homosexual, and a spirited defence by a ‘Law Reform’ movement grew within the gay community, its meticulous submissions to a parliamentary committee succeeding in tempering the legislation. Nonetheless, three amendments were finally made to the Immorality Act: the first was to raise the age of consent for male homosexual acts from sixteen to nineteen; the second was to outlaw dildoes (which, police reported, were the primary tools of the trade of lesbianism). The third was the infamous ‘Men at a Party’ clause, which criminalized any ‘male person who commits with another male person at a party any act which is calculated to stimulate sexual passion or give sexual gratification’. Most absurd was the definition of a ‘party’: ‘any occasion where more than two persons are present’. At the Wychwood bash, the only black people present were in the kitchen, but what was happening under the bricks at Peter’s place was a party by any definition.

I grew up a few kilometres north of Forest Town and, as an adult, have lived close by. When I am in Johannesburg I drive through the suburb once or twice a day. Each time I do, I get goosebumps thinking of the atomized geography of my home town; of these two outlaw gatherings that happened contemporaneously in the same leafy old randlord suburb: one in the main house and one in the boy’s room, each off-limits to the other.

In the 1970s, Phil befriended Charles, a man from Zululand who had left his wife and children back home to come work in the city. Like thousands of other migrant labourers, Charles rented a room in one of Johannesburg’s single-sex hostels – Mzimhlophe, on the northern fringes of Soweto. Charles had met a white man and moved into his house in the suburbs; his room was thus available, and he sublet it to Phil.

For the first time, Phil and Edgar had their own space in the township. It was tiny, not more than two metres squared, with a single bed, a little table and a wardrobe, but ‘it was a special place for us’, Edgar told me. ‘We called it “our flat”. We would pay rent every month. It was exciting to have our own place.’? The keys would be left in a safe place at the hostel and the men would make their way to the ‘flat’ individually, for an hour or for the night if they had a partner. On weekends, if they could both find a way of being away from their families, they would be in the flat together: the tone in Edgar’s voice as he described this suggests nothing less than the bliss of newly-weds.

Most of Mzimhlophe consisted – like all single-sex migrant hostels – of communal dormitories, where workers were housed in subhuman conditions. But because Phil’s friend Charles held a good job and had connections (the hostels were tightly controlled by indunas from Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s Inkatha Zulu nationalist movement), he had managed to secure a single room along a lane reserved for foremen and other senior workers. This lane, just to the left as you entered the sprawling compound, had been commandeered by gay men. Here Edgar and Phil could go about their business protected not only by a single-sex environment where many men took ‘wives’ but by the extreme alienation of the place. ‘We were left alone,’ Edgar told me. ‘People in the hostel, they just drink for themselves. At the hostel you just live your own life. You are not curious about other people’s lives. It was cool.’

Anti-apartheid social scientists and activists have conventionally viewed the single-sex hostels as prisons, where sexual behaviour was a pathological symptom of the economic system that produced the hostel in the first place: men had been forced off the land and away from their families to work as the ‘black gold’ of the South African economy. Certainly, the conditions in the hostels were degrading and often violent. And certainly, as in prisons, many of the younger, more vulnerable men were – and still are, on the mines – forced to become ‘wives’. More recently, historians have begun to understand the homosexual relationships among migrant labourers as a form of resistance rather than oppression but this reading, too, is over-determined. Some men – like Charles, like Phil and Edgar – simply were homosexual, and found their space at places like Mzimhlophe.

When Phil and I spoke about the confounding legacy of the hostels, he told me the story of his sole visit to a mine hostel, where life was far more regulated than in township hostels like Mzimhlophe. He had been invited by a friend, George, whom he had met at Mzimhlophe, to attend a dance. When he got to the hostel with a group of friends, however, the induna at the door did not know of a George and would not admit him. Eventually, Phil managed to explain who George was and the induna exclaimed: ‘Oh, you mean Margaret! James Bond’s wife!’ Phil was surprised to discover that George had transformed into a glamorous and buxom hostess; James Bond was the chief induna, and so Phil and his friends were made especially welcome. During the dance, Phil was particularly entranced by a beautiful young Shangaan girl who could not have been more than eighteen and who danced with seductive shyness. Phil wanted her immediately but she was not available, as she was mourning her husband who had died in a mine accident six weeks previously. At four o’clock, those on the evening shift had to change and go back to work, and the girl came back to say goodbye before going underground. ‘I couldn’t believe it,’ Phil told me. ‘It was a man in gumboots and a helmet and overalls. He was a man, now, going underground, to work, maybe to his death, in that furnace, with the heat and the noise. But he was just a little boy; that’s what I knew from having seen the dance. How can you send a child like that into the earth?’

Edgar and Phil lost their room in the mid-1980s, during the township uprisings that eventually shook apartheid off South Africa even as they stole Phil’s firstborn son. Mzimhlophe, like all hostels, was a stronghold of the anti-ANC Inkatha movement; the Zulu migrants who lived there would go on the rampage in Soweto against the township residents, generating much antipathy against the hostel, which became a fortified bastion. It was no longer safe to go there, so Edgar and Phil stayed away. When Charles tried to get the room back for them once things had settled down, he was told that it had been commandeered by another man who had paid the indunas protection money to keep it.

At roughly the same time, the parties in town, at places like Roger and Sello’s home, stopped abruptly. Phil blames politics for this, too. ‘In 1986 there was a lot of hatred instilled in black boys. We would try to get them to come to town but they were not interested in being with whites any more. And police were also suspicious when they saw a group of blacks in town: they would harass you.’ Roger remembers being stopped, taking Phil and Edgar back to Soweto during one of the States of Emergency; he had to pretend that they had been waiters at a function and that he was driving them home after dark.

As apartheid collapsed and the new society began to form itself through the violent years between 1986 and 1994, gay life too began to change. As the inner city went ‘grey’, so too did the gay bars and clubs become mixed: Edgar loved the Skyline, Johannesburg’s oldest gay bar on Pretoria Street in Hillbrow, which was rapidly becoming the centre of the city’s black gay youth scene; Phil preferred the more mixed Champions, opposite Park Station, where he kept his own bottle of gin behind the bar and was feted as a village elder. You no longer needed to trawl the Park Station toilets or find your way to the white suburbs for sex. If you could pay the entry fee, you could go to sex clubs like Gotham City or, later, the Factory; once the anti-pornography laws started crumbling, you could slip into film booths at Adult World. Phil’s friend Charles broke up with his white boyfriend in the mid-1990s but did not need to move back into Mzimhlophe: by this point, black people could rent flats or rooms in town.

Meanwhile, in Soweto itself, places like Scotch’s opened, and a younger generation started to reject the ‘After-Nine’ identity. For one thing, the youth uprisings from 1976 onwards had constituted a generational revolution: young people were no longer bound to their families, or tradition, in the same way. As a black middle class began to grow, young black professionals got their own places, in Soweto itself or in formerly white suburbs, making the space that people like Roger had once provided. After he lost Mzimhlophe, Phil found a lover who had not married and who had his own place in Soweto. Perhaps because he had the space, Phil says he experienced real love – and heartache – for the first time with a man.

III

The first thing Phil noticed when he regained consciousness at Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto in May 2003, was that his wedding ring was missing. His wife explained to him that he had driven his car through the intersection on the Old Potch Road and crashed into a truck. He had been in a coma for several weeks. Phil assumed, as did everyone, that he had been robbed by a bystander, but it came to him, after a while, that there had been someone else in the car. It took him a full year to recollect, he told me, that the person who must have taken his ring was a young man he had just found at Scotch’s Place, and that when the crash happened they were on their way to find a place to have sex.

To be found injured in a car crash with a boy you have just picked up would have been, of course, one of Phil’s worst nightmares, and so once he remembered the circumstances he was deeply relieved. Phil holds it as a matter of pride that none of his scores of pickups had ever exposed him. But this implies a code of honour among ‘After-Nines’ and the men who go with them: they are a particular tribe, a particular clan, and they watch out for each other. The boy had violated this code, and the only time I felt Phil’s anger flare during our time together was when he described how he had bumped into the boy two years later. ‘I told him he would never amount to anything and would land up in jail. He is sitting there now. I have been

proven correct.’

Phil told me this story in March 2010 as we were driving with his friend Charles through Soweto to the Maponya Mall to have lunch. The mall is famous for the sculpture of a huge, trumpeting bull elephant at its entrance, a clarion to the new black middle class; with shops selling high-end brands, it had been built by one of Soweto’s pioneer entrepreneurs and is much touted as a symbol of the entry of the township into global consumer culture. It is also, I discovered as the three of us sashayed through its neon avenues checking out the rather dubious talent, a prime location for what Edgar, had he been with us, would have called ‘fishing’. Positioning themselves on a terrace overlooking the entrance to the mall, Phil and Charles indulged in low-camp repartee, with much talk of amagamane (young pumpkins), ama-pinchies (peaches), amacasiba (thighs) and isiphefu (bums). Phil, in particular, complained bitterly about ageing, even after it was pointed out to him that he currently had a devoted young lover whom he seemed to have no trouble pleasing.

Charles was the man from whom Phil and Edgar had rented their room in Mzimhlophe; he was now in his mid-sixties, shy and handsome, with the distended ear lobes of a traditional Zulu man. He seemed to have replaced Edgar as Phil’s special friend; the two men spoke every day and Charles visited him a couple of times a week. As we walked back to my car, Charles muttered something I could not understand, and Phil affected outrage, pinching him in the side as I had seen him pinch Edgar over a decade ago at Scotch’s.

‘What was that about?’ I asked.

Phil translated what Charles had just said to him: ‘I noticed you swinging your hips, and at first I thought you were doing it to attract the small boys. Then I realized it’s only your limp from your accident.’

I had hoped that Edgar would join us at the Maponya Mall too, but he was not answering his cellphone. Phil told me his old friend was bedridden; he believed it was cancer and was annoyed with Edgar for refusing to consult Western doctors. ‘That old Zulu has gone back to Zululand in his head!’

The two men barely ever saw each other any more. In recent years, they had been getting together once a month, when Edgar went to Baragwanath Hospital to collect his medication. Phil, who lived nearby, would drive over to meet him, bring him back to his house for tea, then take him home. But now Edgar was too ill to get to the hospital and Phil did not like to drive the distance, all the way across sprawling Soweto, to Edgar’s home in Protea.

The last time I had seen Edgar had been in mid-2008, when I had asked him to participate in an exhibition I was curating, which told the story of Johannesburg through eight gay, lesbian and transsexual people. Although he was already ill and lame – he needed a wheelchair – he had agreed to take part, as long as we did not identify him in any way. For this reason, we used as his signature portrait a close-up photograph of his left hand, blown up into a four-metre-high banner; his wedding ring a flash of gold on the ashen parchment of his wrinkled hand.

We had arranged for a van to transport him to the museum, and I wheeled him into the auditorium for the opening event. I had not seen him for a few years and I was startled at the change: the only memory of his heft was to be found in the folds of skin hanging off his gangly frame. Still, he was sexy, an outrageous flirt, his face igniting every time a younger man paid him any attention. I introduced him to C and he approved. ‘Very handsome and charming,’ he told me, adding that despite much opportunity he had never been with an Indian man himself. When I mentioned our nuptual plans, he delightedly offered himself as the priest, and we chuckled a little about how we would spirit him out of his family home for the ceremony.

I watched Edgar intently as the South African Chief Justice, Pius Langa – a black man of his age – gave a keynote address underscoring the constitutional equality that gay people now had in South Africa. ‘This is wonderful!’ Edgar said to me afterwards, gesturing expansively at the crowd. ‘Just seeing these young people makes me feel free even if it is too late for me.’

A week or so after our visit to the Maponya Mall, Phil decided to drive over to Protea, to check up on his old friend. When he arrived at the house, he learned that Edgar had died a few days previously, after a night in the hospital. The funeral had not yet taken place, however, and he was able to attend; there were only two other gay men present.

Phil called Roger to tell him about Edgar’s death but when Roger tried to get information about the funeral Phil became vague and confused. Roger worried, he told me, that Phil might be developing memory problems. But it seemed to me that something else was going on. Phil would not even have known about the funeral had he not arrived unexpectedly at Edgar’s home. He must have understood that his friend was being claimed back in death by family and clan and church, from the world of the After-Nines.

Phil’s wife, Mo, died in 2008, after a lengthy and very debilitating illness. A year later, Phil told me about it as we sat in the living room of his house, a tray of mid-morning tea and biscuits between us, the sliding door closed against the prying eyes of the housekeeper bustling about the kitchen. If Mo had been alive, it would have been impossible to be in the house at all.

Phil had devoted himself, for several years, to looking after her, and he remembered her suffering with great sadness. Clearly her death had given him more space – his young lover J.B. now stayed over once or twice a month, for example – but he did not understand this as new freedom. Since Mo’s death, ‘a lot of whites who I have met have asked me: “Phil, why don’t you come out into the open?” I say: “I’ve lived a lie for so long, I would hate to bust this balloon. I don’t know what would happen. So I would rather take this with me, to the grave.”’

J.B. had been with him through ‘thick and thin’, through Mo’s illness and then the bereavement period, and Phil’s family had come to accept the young man’s presence. Still, as always, he had needed to dissemble: he told his children that J.B.’s father had been a work colleague who had died young and that he had made a death-bed pledge to look after the boy. ‘You have to lead the life of a lie,’ he told me. ‘You have to tell lies and be careful you are not caught. That has been my life.’

As if on cue, Phil’s sister arrived unexpectedly with a box of cabbages she had brought back from the countryside. While she was making her way across the lawn, Phil and I hurriedly agreed on a story to explain the unusual presence of a white visitor: I had come from England with a gift from my father, who had been Phil’s boss many years previously. I received the sister’s warm greetings – ‘Welcome to Soweto! You are at home here!’ – before Phil scuttled me out of the house.

Earlier, I had taken him into the garden to photograph his wedding ring, for an image I hoped to use alongside Edgar’s. We had chatted playfully as he lured the winter sunlight onto his golden signet by shimmering his hand, and I told him about my own ring at home, on my desk in Paris.

‘Gay marriage!’ he exclaimed. ‘Who would have believed? Edgar and I used to say, “Not in our lifetime . . .” It’s like how we felt at the end of apartheid. You have to pinch yourself. It was a white wedding, I trust?’

I laughed. ‘No, Home Affairs!’

‘Which one?’

‘Edenvale.’

He fired a round of incredulous clicks off the roof of his mouth before exhaling a laugh, or a cheer, that drew his skin tightly, in wrinkled folds, around dancing cornflower eyes.

[*] At the request of both Phil and Edgar, all the names in this piece are pseudonyms. Certain biographical and contextual details have also been changed to protect confidentiality. Some of the material used here is from interviews conducted by Zethu Matebeni and Paul Mokgethi for Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA), Johannesburg.

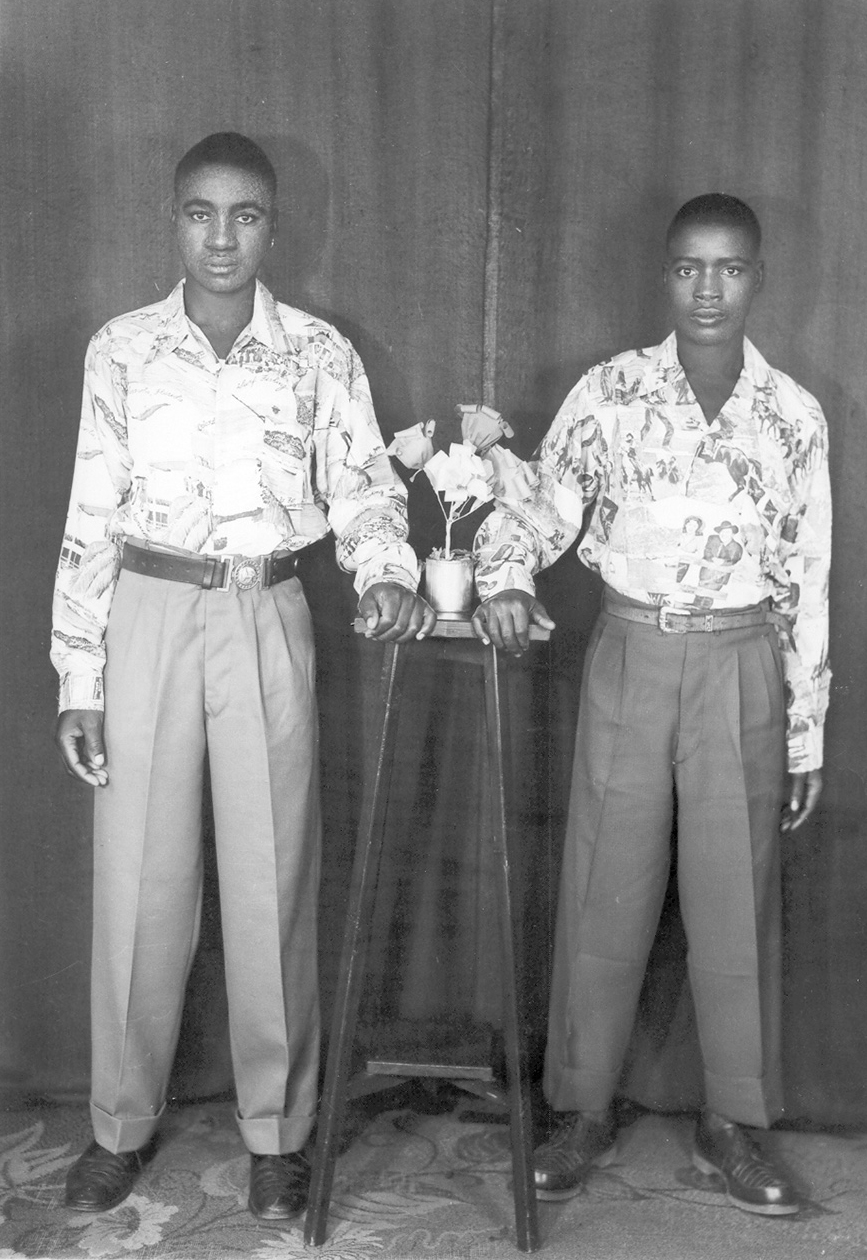

Photograph courtesy Angus Gibson, from a photographer’s studio, Marabastad, date unknown.