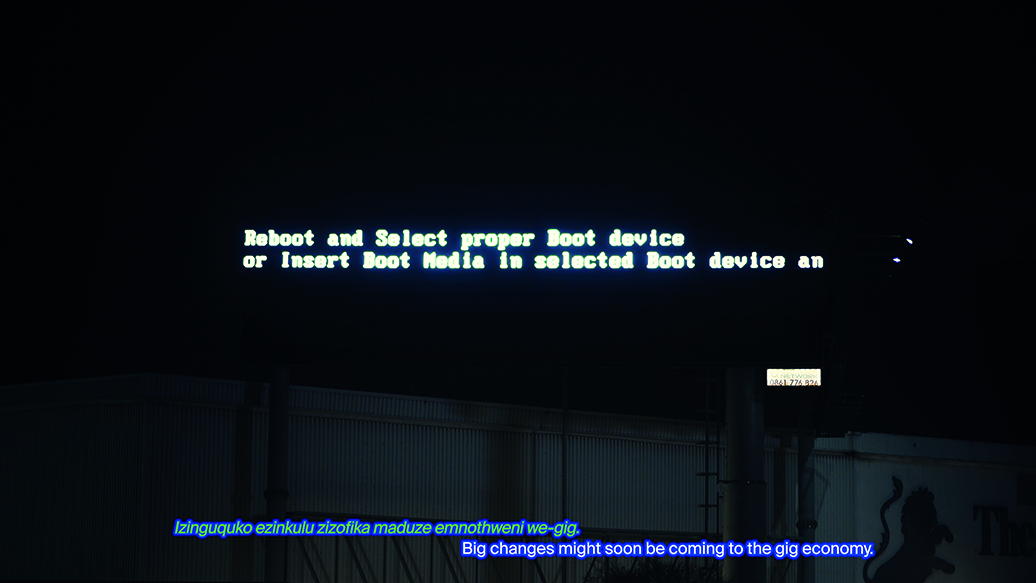

The old romantic warning not to trust a machine more than one’s own intuition has renewed urgency in the digital age. When Salvatore Vitale began working on the project ‘Death by GPS’ in 2022, he wanted to pursue the pitfalls of automation bias: those accidents where drivers blindly follow their GPS off bridges and cliffs. Gradually, Vitale’s focus became the human labour that delivers the illusion of automation in the first place: the people driving camera-equipped cars to populate Google Maps, the Amazon Mechanical Turks who complete online tasks for employers. ‘We believe that these systems are fully automated,’ Vitale told us, ‘but we’re not there yet.’

‘Death by GPS’ includes photography, text and video, all shot, filmed and composed in South Africa. Most of the material was created by freelancers Vitale hired on the online platform Upwork. Without giving them any specific direction, he requested the freelancers document their daily lives and working routine using video and photography. He offered an hourly wage of between $25 and $30. Although the job vacancies were geolocated in South Africa, soon he was receiving offers from freelancers willing to relocate from Switzerland, Italy, the UK and the United States. Such was the pull of a decent wage, even among Western countries.

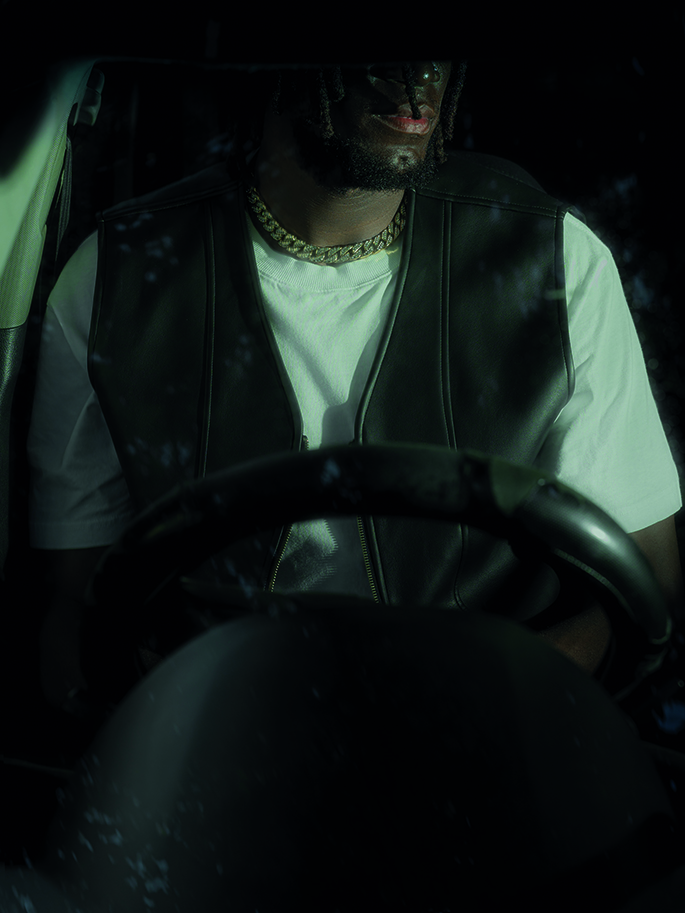

Vitale worked with around fifty people, young and old, and from various social classes. Participants – primarily from the Gauteng province – provided footage of themselves at work: they filmed their desks, their computer screens, their commute. Illustrating the common elision of the professional and the private, there were also clips of freelancers sleeping, clubbing, golfing. Interspersing his own imagery with the material the freelancers had collected, Vitale created the speculative documentary film I Am Human. He also photographed the freelancers he had hired in their personal environments, which often overlapped with their workplace. The material that follows is a combination of stills from I Am Human, and photographs taken by Vitale.

Vitale organised his project in South Africa because of the country’s continuous history of hard labour and exploitation. From the colonial period to the present, South Africa has been a major source of diamonds, gold and platinum. Under apartheid, it added uranium to its inventory, which it supplied to Taiwan and Israel. In post-apartheid South Africa, forced and pittance-level labour persist in mines around the country. Illegal miners, known as ‘Zama Zamas’, have flourished around dismantled, close-to-exhausted sites.

‘When you speak about mining, especially of gold and platinum, you are talking about a very old form of colonial exploitation,’ Vitale explained. ‘But the material extracted from many of South Africa’s mines fuels technological life – it’s what enables IT workers to operate online.’ In a series of deceptively soft images that span from miners breaking earth to tech workers breaking their phones, Vitale juxtaposes the opposite ends of the supply chain: two parallel trajectories of destitution and precarity that each depend on the other, but hardly ever meet.

Introduction by Granta