Every day, barring Thursdays, which are kept as holidays in this part of the southern Democratic Republic of the Congo, people try to discover something of worth in the soil beneath the city of Manono. Men, women and many children leave their homes early each morning, shovels in hand, and dig into the fine, sandy soil until they can scoop out a couple of bags of what looks like gravel. The city, which is home to more than 300,000 people, is collapsing into the millions of shallow, square holes that have been cut into the ground. ‘There are minerals all over this town,’ Jean Kiluba Nzenga, the administrative secretary of the local mining ministry told me when I visited, the year before last. ‘People dig in the foundations of houses. If we weren’t here to intervene and stop people, every building would collapse!’ Approach any of the shallow pits and ask the shovelers what they are looking for and they will invariably reply, ‘Cassi!’

The word is said as if the mere invocation of the mineral for which they search will assure them of profits for the day. The pebble and dirt the people in Manono are digging out generally contain what are called minerais noirs, or ‘black minerals’. Cassi is cassiterite, an ore of tin, the most common of the rocks these miners are searching for. That is why this city is pocked with the rusting apparatus of a tin mining concern.

Another rarer find among the gravel is coltan – columbite-tantalite – a black rock that contains tantalum, a metal that is used in electronics to make capacitors. It is one of the heaviest metals, and it has a very high melting point.

Both cassi and coltan are much in demand by a modern hi-tech low-touch world. But in spite of the demand, Manono doesn’t see much benefit. ‘The problem is that mining companies don’t respect their obligations to the local community,’ Kiluba tells me. ‘What people need here is infrastructure. Roads, buildings, communication, everything.’ He goes on to list the minerals in Manono: ‘cassiterite, coltan, which is very valuable, wolframite, lithium, quartz, tourmalines, emeralds, copper.’

It is lithium that has most interested investors recently. An Australian firm called AVZ Minerals has staked out a huge deposit of spodumene rock here in Manono. Spodumene contains lithium, a metal that is a key ingredient in everything from mobile phones to the electric vehicles that use lithium-ion technology to power their batteries. (The metal and its compounds are, AVZ pointed out in a 2019 Australian Stock Exchange Filing, also used to make lubricant greases, glass, ceramics and psychiatric medication.) For the ‘green transition’, lithium is perhaps one of the movement’s best hopes, allowing a future in which fossil fuel emitting vehicles are replaced by cars, planes and even boats that use stored electricity produced by renewable sources.

Lithium is abundant on the earth’s surface, especially in Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, but the number of mines coming online barely scrapes the surface of the amount on the metal that will be needed if the world is going to completely electrify transportation. (The movement of lithium ions releases electricity in a lithium-ion battery.) Some metals men, like Robert Friedland, the chief executive of Ivanhoe Mines, a huge copper mine in the south of Congo, have taken to calling this disjunction of supply and demand, ‘the revenge of the miners’.

In Congo, the West worries it is being outmanoeuvred by China, and AVZ might provide a rare counterweight to that trend. In a phrase popularised by the academics Hal Brands and John Lewis Gaddis, policymakers in Washington and Whitehall believe the West and China have begun a ‘new cold war’. One of the key staging grounds for that war, the political scientist Brett L. Carter argued last year in Foreign Affairs, is Africa. ‘China began to replace Western countries as Africa’s key economic partner,’ he wrote. ‘In 2013, China supplanted the United States as Africa’s primary export destination. By 2020, China was responsible for more construction in Africa than France, Italy, and the United States combined. Chinese-backed infrastructure projects opened markets and increased living standards and, at the same time, served Beijing’s interests.’

During the first Cold War, access to oil was key. The prizes this time around are materials like lithium and cobalt, which will ostensibly power the future. The Congolese, trapped in the middle, are usually forgotten at best, and at worst used as pawns in order to acquire these minerals. In a place like Manono, though, all this geo-strategizing can feel downright odd: the town is so remote that the electricity cuts off midway through each evening, and the surrounding region is plagued by crisis levels of food insecurity. What’s more, disputes with groups of isolated peoples in the nearby forests have led to massacres and mass-rapes of Twa pygmies as well as reprisal attacks that have struck into the heart of the town. In December 2016, a Twa militia even assaulted the centre of Manono armed with bows and poisoned arrows, killing at least forty people.

On a sweltering day in March 2022, at Camp Coline, AVZ’s exploration office on the edge of town, Mick Brown explained the origin of AVZ’s presence in Manono to me. We sat at a conference table under the obligatory portrait of Congo’s president, Félix Antoine Tshisekedi Tshilombo. Brown, who works for AVZ, is a geologist from western Australia, and, though unfailingly friendly, displays the kind of reserve that a life studying rocks tends to induce. When the subject is geology, however, he becomes animated. Brown has scoured Australia for minerals. Since the late 1980s, he has explored for gold at Gidgee and Wiluna, iron ore at Bungaroo Creek and in the Yandicoogina Channel. ‘Once a mine becomes active, I tend to move on. It becomes like a city. Too many people,’ he told me. He hardly gets back to see his family. ‘I like it when I’m out on the frontier, finding new things.’

Manono’s mineral wealth, Brown explained, comes from a series of subterranean rock formations called pegmatites that were formed in the magma chambers of ancient volcanoes. Sometimes described as ‘cigar-shaped’, these long, rich deposits of minerals were deposited across a broad swath of land from what is now southern Congo, stretching up into southern Uganda sometime during the formation of a supercontinent called Rodinia around 1.2 billion years ago. Within the Manono pegmatites, large crystals, especially quartz, as well as granite, are found bound together in rough-grained rock with valuable ores like cassi, coltan and spodumene.

In 2017, AVZ began drilling forty-two kilometres of holes into the ground to conduct samples, or assays, of five of the pegmatites, which they say total more than thirteen kilometres of length. The ground, they estimated, contained 400 million tonnes of lithium rock, or spodumene. In 2019, Nigel Ferguson, the group’s CEO, said that the firm was ‘confident that the project will continue to develop into production and potentially become a world leading source of lithium and tin.’ As Brown emphasised when I first met him at a restaurant in Manono – ‘it’s the world’s largest lithium deposit. There, I like saying that.’

A world-class lithium deposit could change things for people in Manono. AVZ have planned to bring a modern power plant and a road to the town. The miners here often earn not more than a few dollars a day. There is a risk that Manono will be mined and then abandoned, a little like it was by the Belgians and later the Zaïrian state. Congo is littered with such projects, vines clawing at arrested versions of modernity. All the profits could also go into the pockets of corrupt officials. But there is also hope: some communities, like the town of Bunkeya, to the south of here, have used mining royalties, paid to the central government, to build schools, clinics and farms.

When I visited a bend in the Lukushi river not far from Camp Coline, hundreds of people stood knee-deep in the muddy water, washing minerals that they had just dug out of the ground. The Lukushi is a tributary of the Luvua, the Luvua a tributary of the Lualaba, and the Luluaba a tributary of the great Congo River.

Piles of minerals were laid in the sun on split orange sacks. Ziani Mwamba, a fifty-three-year-old mother of nine, told me she has been working in the cassi and coltan mines for around two months. She wore a red paisley bandana and a tank top with a length of brightly-patterned wax cloth wrapped around her waist. She was once a peanut, manioc and maize farmer, she explained, but she needed to make more money to educate her children. As in much of Congo, almost all farming around here is subsistence and brings home just about enough to support a family, but not to pay for schooling. Education is nominally free but in reality the state leaves teachers’ wages unpaid and parents end up shouldering the financial burden. Mwamba, her husband and four of her children dig minerals out of a nearby hill and then lug them here to be washed. ‘We come here to make money,’ she told me. ‘We come here to make money to pay for our kids’ school, and for our meals, our food, for the children at home.’

Manono’s cathedral still bears a plaque with the Latin legend Géomines Aedificavit 1942. Like an inscription unearthed in Greece or Rome, it commemorates an entirely different world, when Manono was a company town, run almost exclusively by a mining firm, with all sorts of contemporary amenities for its workers: an airport, grassy football fields, an Olympic swimming pool, a modern power plant, and of course the red-brick cathedral, which is built in a sort of dour and imposing Flemish style. Of these, only the cathedral still functions. The pool is cracked and clogged with weeds and the power plant has no roof, let alone machinery.

The mines beneath Manono were first mapped out in 1906. Congo was still officially the private property of King Leopold II, which he had seized in 1885. By the time Manono’s mines were being studied, Belgian colonists had already brutally exploited the land for its ivory and then its rubber, killing an estimated 10 million people. As Congo came under state control from Brussels in 1908, a new generation began to exploit the riches beneath its soil. Part of this new wave of exploration was the creation, in 1910, of the Compagnie Géologique et Minière des Ingénieurs et Industriels Belges, or Géomines. On the company’s share certificates, the firm’s ‘Social Seat’ was listed as Manono, Belgian Congo, but the ‘Administrative Seat’ – head office – was in Brussels.

In the boom years before the Second World War, Géomines could afford to spend on infrastructure since it had exclusive access to the area’s tin deposits and enjoyed a monopoly position. This meant that in times of low tin prices, the company could choose to mine in areas with a lower percentage (what miners call ‘grade’) of tin in the ore, and allowed it to invest liberally in the latest equipment. The machines that were brought in to replace people now lie rusting around town.

Over the years, more pits were dug by Belgian miners with African labour. The most famous of these were the Roche Dure and Carrière de l’Est quarries, incidentally the places where AVZ now say the highest grade of lithium ore can be found. Next to the mines, mounds of rejected earth were piled, pale smooth hills of quartz and spodumene, a mineral which the Belgians thought useless. Today, these heaps tower over the town, waiting for someone to truck them out and process them into lithium concentrate. Despite the rush for lithium, the cost of spodumene, which must be processed into lithium carbonate to be used in batteries, is so low that mining of the ore by workers using hand tools as is done for cassi and coltan could never make economic sense. The only thing to do would be to mine it industrially and ship it out in bulk quantities.

Géomines operated their mines until Congo won its independence in 1960. The southern state of Katanga separated from Congo and was recaptured by the United Nations and the Congolese state. The area surrounding Manono was a warzone as rebels and the central government fought for control, but former colonists kept order in town by using harsh methods. ‘Every Indigenous person who behaves incorrectly towards a white person or who “shows off” is automatically thrashed before being tossed into a cell,’ an agent of a Belgian mining concern wrote approvingly to his superiors in a confidential cable from 1962 that I found while researching the region in the Belgian State Archives in Brussels.

In 1965, the dictator Mobutu Sese Seko took power with the support of the United States. He managed to quell violence and secessionism in his country using a combination of brutality and bribery. In 1967, the country’s mines began to be nationalised by Mobutu. In Manono, he set out a fifty-fifty deal with a new, Congolese-owned, company named Congo-Étain and, later, Zairetain.

As so often happened under Mobutu’s reign, the company became a vehicle for those in his orbit to enrich themselves. Like the town’s swimming pool, salaries began to dry up, and the football fields sprouted weeds. Foreign workers started to leave. The mines continued to be exploited until 1982 when tin prices bottomed-out – tantalum was still a sideshow. There was now no more revenue for the country’s venal elites to steal, so they began to scavenge whatever equipment and infrastructure they could. All that is left of the town’s famous brewery, which made a beer called ‘Nyota’ (Swahili for ‘star’) until sometime in the 1980s, is a crumbling building off the central roundabout.

Congo spiralled into war and disaster in the 1990s as the rebel leader Laurent-Desirée Kabila took power. What business was left in Manono evaporated when Rwandan troops seized the town in 1999. The Rwandans took control of the cassi and coltan mining along with a proxy rebel group, the Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie. Even today, Rwanda, a country to which the British government has deemed it safe to send asylum seekers, continues to fund militias in Congo, and the Rwandan government is accused of stealing resources to enrich its ruling class.

Coltan, the tantalum ore, has frequently been connected to armed groups by global NGOs, and it carries a quasi-mystical reputation in some Congolese circles. The anthropologist James H Smith recounts in his book The Eyes of the World being told by a militia fighter that coltan was used in his group’s magic rituals because it ‘contained and magnified the power of the forest’.

Towards the end of 2000, the PlayStation 2, which contained a tantalum-heavy capacitor, was released in the US and Europe. At the same time, the Second Congo War between Rwanda, Congo, Uganda and a plethora of militia groups, was entering one of its most violent periods. Tantalum underwent a drastic price spike on international spot markets, jumping around 1,000 percent in value, fuelled partly by Christmas demand for the console. A faction of the Rassemblement Congolaise even started its own mining company. ‘During that time, we would avoid the mines,’ Pascale, a cassi and coltan trader told me in Manono. ‘The Rwandans would steal everything, and they brought their own militias to do mining.’ Wealth and weapons flooded into the Congolese interior, and journalists came to know the period as ‘the PlayStation Wars’.

Around about the same time, in the early 2000s, Kabila called on local militia groups to fight off foreign enemies and their domestic proxies. They were known as Mai-Mai, after the Swahili word for ‘water’, because they believed that water, blessed by a fetish priest, would ward off bullets. The most famous of the Mai-Mai operating around Manono was the self-styled Nkambo, or ‘Lord’, Gédéon Kyungu Mutanga Wa Bafunkwa Kanonga, a wild-eyed former teacher. Gédéon, who added the Kiluba epithet ‘Wa Bafunkwa’, or ‘already dead’, to his name, was accused of using cannibalism to terrify local inhabitants and of recruiting child soldiers. He was convicted of war crimes by Congo’s government in 2009.

The central government was barely able to rule the country, and an area as remote as Manono was far beyond their control. Rumour had it that powerful officers in the army were using Gédéon and his militia to scare people away from the area as they became wealthy from the region’s cassi and coltan. Thierry Mukelekele, a former spokesman for Gédéon, told me that politicians in the capital were complicit in the violence and also earned money from the mines.

At his trial, Gédéon was sentenced to death, but he and his wife managed to escape. Some people claimed that the military wanted to use him to pillage the area around Manono once again. ‘It was easier for him to run away when the army was there than when the police was there,’ Moïse Katumbi Chapwe, the governor of Katanga at the time, told me, noting that ‘the day he got out from the prison is the day the army replaced the police at the facility’. Katumbi believed that elements in the army had sprung him from prison to do their dirty work. Queue two more years of senseless violence, with Gédéon ostensibly aiming to separate Katanga province from Kinshasa’s rule (he renamed his militia ‘Bakata Katanga’, or ‘Cut off Katanga’ in Kiswahili). Katangan independence has been an aim of many in the region since decolonisation, when a short-lived state of Katanga existed for almost three years before being crushed by United Nations troops in early 1963. As Gédéon’s militia threatened civilians in the early 2010s, Manono formed one vertex of what became known as ‘the Triangle of Death’. Over 4,000 people were displaced, according to the UN, and estimates of the dead are hard to come by. Gédéon would voluntarily disarm again in 2016 and then escape house arrest in 2020.

Gédéon is still at large. In a video released just after the most recent Congolese elections in late 2023, he stands at the center of a small village that Congolese journalists believe to be to the south of Manono. He is wearing the red, white and green flag of Katanga, sewn together into a kind of stocking-hat, gum boots and a teal windbreaker. Watched by a crowd of villagers, he reads a declaration of Katangese independence in Swahili. When I asked Katumbi, who was running for president at the time, what he thought of the declaration, he scoffed, ‘and how do you think he will make a separate Katanga? With bows and arrows?’

After the PlayStation Wars period, coltan plummeted in value as trading slowed and long-term contracts were negotiated by technology companies, but the damage was done. An independent panel of experts reported to the UN in 2002 that eighty-five multinational companies, among them twelve British firms and household names like Barclays and De Beers, had profited off Congolese minerals during a war that would kill an estimated 5.4 million people, more than any conflict since the Second World War.

Moves were made to classify tantalum and tin, as well as tungsten and gold, as ‘conflict minerals’, and a tagging system called the International Tin Supply Chain Initiative, or iTSCI, was introduced. ‘The narratives supporting these advocacy themes rely on a colonial image of Black and African savagery that requires white saviours,’ Christoph Vogel writes in Conflict Minerals, Inc., ‘to bring peace, order and development.’ His book shows how the initiative has given rise to an illegal economy of tags and increased violence. iTSCI has driven down prices, directly affecting the lives of artisanal miners in places like Manono, he argues, and has entrenched ‘the exclusion and marginalisation of mining communities that became trapped in markets monopolised by powerful end users.’

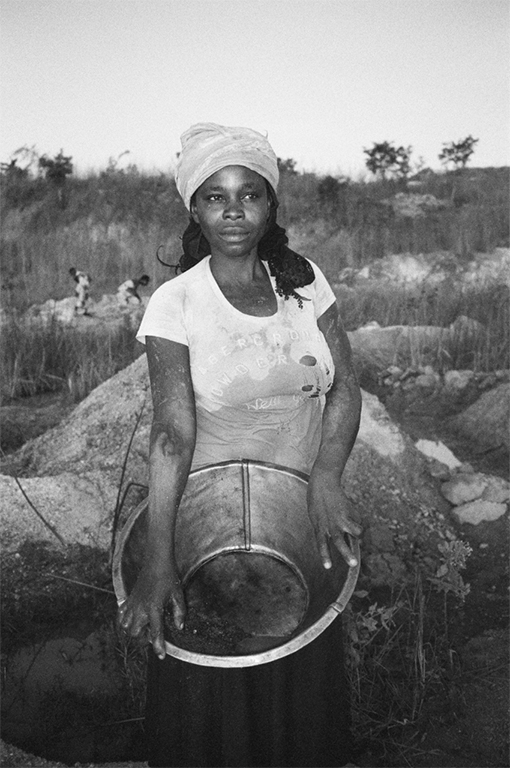

When I visited Manono’s Carrière de l’Est in 2022, it had become a vast small-scale mine at the eastern end of the city. In the golden light of the late afternoon, men and women worked up to their waists in mud and puddles. Jolie, one of the miners, proffered a metal pan that gleamed in the early evening sun. ‘I come here at seven in the morning and leave at six in the evening. Today I found coltan. Maybe eight hundred grammes, maybe seven hundred grammes. I might be able to sell it for about fifty dollars,’ Jolie told me, excitedly. She would be able to feed her three children for a couple of weeks on what she earned from selling the minerals. Inside, the precious black rocks, chunks the size of a thumb, glistened.

The war years have left Manono feeling hollowed, a carcass plucked clean by scavenging birds. Buildings rot, a stripped power station is taken to pieces for scrap, houses are reduced to deformed grids of brick – here, a right-angle signifying where a wall might have divided a kitchen from a living room; there, doors with broken panes of glass; above, a roof stripped and signified only by rusted metal ribs – their floors carved into tell-tale square pits. People are destroying the ground beneath them in the rush to find cassi and coltan.

Once dug from the ground, the shovelfuls of rock are bagged and humped to the Lukushi river where they are sieved and washed by yet more women, children and sometimes men. ‘It’s after work that we go to sell in the other corner there where there are places to sell our product,’ Ziani Mwamba, the miner with the red bandana told me.

The ‘other corner’ was a clearing under a tree at a crossroads. Men clustered around a rusting Belgian steam engine and haggled over prices. Women with bloodshot eyes cooked the rock on metal discs until it turned to dark grey powder. One of them was Anita Kikungwe, a woman in a black-and-white striped shirt with an improbably tidy lace fringe. The smell of her baking minerals stuck in the mouth. ‘When we smell this smoke we have some problems with our eyes, but we need to do it to dry this cassi and to be paid at a good price,’ she said. Humid cassi is worth less.

Kikungwe had been working since seven a.m., roughly nine hours. She was thirty-four and had been digging for minerals since she was thirteen. She has two children, who stay at home when she goes to work. Her younger sister teaches them, as Kikungwe cannot afford to send them to school – despite the promises of Tshisekedi, Congo’s president, to provide free education to children, schools often charge registration fees that are impossibly high and demand other payments that parents cannot afford. After all, many of the teachers are not paid regularly by the government, if at all. ‘The objective is that the minerals will be dry, so I will be well paid.’ Nearby were potential buyers: Monsieur Pascale, who sat nearby toting a leatherette shoulderbag stuffed with bills, and Monsieur Freddy, to whom Mwamba usually sells her minerals. She estimated she can make between $1 and $7 a day.

Monsieurs Pascale and Freddy loaded sacks of mineral onto motorcycles and brought them to the town centre. There, they ducked into gates built into a stretch of buildings on Manono’s high street. Behind the whitewashed facades of these Belgian-built arcades (a Wild West architectural style of row-houses with elegant gables and crumbling interiors) were the trading houses, which are known as comptoirs.

Stepping into the comptoirs is the first step in a transnational voyage. After all, it is at this early stage, before any international borders is crossed, that Congo’s minerals leave the possession of the country’s people.

Business here is run by Indian firms and a handful of Lebanese traders. Chief among these is Mining Mineral Resources, or MMR. The firm seemed to be trying to occupy a similar space to Géomines in post-Lapsarian Manono, though its ambition has been scaled back to match the town’s dilapidation: public benches about town, including the ancient wooden pews in the waiting room at the airfield, are labelled Don de MMR – gift of MMR.

At MMR’s comptoir in Manono, I saw Congolese men piling cassi and coltan on a concrete floor in front of an office. According to its website, MMR, which is a subsidiary of a group called the Société Minière de Katanga, is based in the city of Lubumbashi to the south. It is certified by no less than eight international supply chain transparency groups. On the website, too, the company engages in the kind of corporate-speak that elides the reality of miners like Kikungwe: ‘We conduct our business with a focus on maintaining and continuously improving the safety and health of employees, contractors, service providers and the public.’ It was not clear that any of MMR’s staff even went to the mines or understood who was digging up the cassi and coltan, let alone focused on improving the miners’ health and safety. They only dealt with money and minerals as they came through the door, sold by traders like Pascale and Freddy.

At the MMR compound, I was ushered into a back room. Mustafa, an Indian mineral trader from the state of Gujurat, sat with his eyes half closed at a desk, in a state of pensive suspension. He never goes out to the minesite, he said, and no, he couldn’t do an interview. The rock is transported out by Chinese truckers, but unlike in the cobalt and copper industry in the south, they had not made inroads into Manono’s tin and tantalum industry.

The extractive industry in Africa, and especially in Congo with its decaying roads, depends on logistics. That much had become apparent to me as I tried to get to Manono. The regular airservice from Lubumbashi had been cancelled and I could only get there travelling on the back of a motorcycle.

It was, in some ways, a journey to a different time. For three days, we drove along roads that were marked as highways but were actually small streams along which people pushed bicycles laden with second-hand clothes. At Mulongo, I had to cross the Lualaba river in a dug-out canoe and bunked with Congolese soldiers who had been sent to quell insecurity around a mine. At Kabondo-Dianda, a railway town that is served by a train that comes so irregularly that sometimes people end up waiting for it for weeks, and that AVZ thinks might be the right nexus from which to freight out spodumene, there was not enough fuel for generators to watch a highly anticipated football game between the DRC and Morocco.

Along the way to Manono, there were endless trucks – carrying mattresses, people, food, minerals – stuck in roads that had turned to soup. People pitched tarpaulins next to them. Their drivers – Chinese and African – sat around small fires. Some had been stuck for months.

The problem for AVZ, or anyone who wants to export lithium from Manono, is that the version of the mineral that they plan to export is only commercially viable when trucked out in bulk. Refining it further would entail a complex and electricity-intensive process. (Coltan and, to some extent cassi, are able to be easily refined into a more concentrated product that is worth more, so the current economics of trucking still makes sense.) AVZ would require huge numbers of trucks going back and forth to a working rail depot – or barges crossing Lake Tanganiyka to the east – in order to justify their mine. ‘They’ll never do it,’ a London mine investor told me when I asked him about AVZ’s plan to mine lithium in Manono. ‘Nobody can export bulk spodumene out of a remote place like that.’

AVZ think they can. Their plan is to build a tarmacked road to get their product out. It would certainly change things for the population, whom Jeef Kazadi Kamwanga, a Congolese journalist who travelled with me, lamented had been ‘left to their own bad luck’ by the central government. Road-building would benefit the mining companies of Manono, and though it shouldn’t be seen as altruism, the knock-on effects would be enormous; towns would be connected and all manner of business would have the chance to thrive. The point was rammed home in one town where the population, unaccustomed to seeing foreigners, gathered around me, politely curious. A man started doing a dance and singing. ‘The whites are going to circulate, the whites are going to circulate,’ he sang. ‘And where the whites circulate, money circulates too!’

On my final day in Manono, I met Mick Brown again for a tour of Roche Dure. He had been working at the site for five months and his rotation was coming to an end the next day. Brown explained that the ore mined by AVZ at Manono would be first pulverised in a gigantic new crusher and then taken to a refinery. AVZ has said they will build a first-stage refinery in Manono to concentrate the lithium somewhat before shipping it. In 2021, AVZ signed agreements with three major Chinese lithium refiners who would buy the minerals and do the expensive and power-intensive task of refining them into battery precursors in China. More than half a million tonnes a year had been pre-sold: Ganfeng Lithium had agreed to buy 160,000 tonnes for five years, Shenzhen Chengxin Lithium 180,000 tonnes for two years, and Yibin Tianyi Lithium 200,000 tonnes for two years.

For a while, it appeared as if AVZ and the Chinese firms had forged a workable collaboration – after all, the Australian firm is what is known as a ‘junior miner’, a small company that begins with a theory about a certain deposit and then shepherds a mine through the exploration and development phases, before larger players step in and take over operations. The endeavour is replete with risks, and junior miners are often hard-bitten, larger-than-life characters who have grown accustomed to living under pressure. Success for these companies is not only based on the richness of the reserve they have developed, but also how much money they can eventually convince a large operator to pay them. Hence the mining engineer John Hays Hammond’s 1911 admonishment that a mine is ‘a hole in the ground sold by a lying promoter to a stupid investor’.

Brown and I hopped into a battered Toyota Landcruiser and drove to the Roche Dure site, the first one the AVZ plans to work. It has been cleared of artisanal miners, who have been warned off the site by the local government. It is not as if there are a lack of sites to mine at Manono at the minute, but there is a very real danger, like at mines in the cobalt-and-copper mining city of Kolwezi to the south, that artisanal miners will eventually find fewer places to work. After all, industrial mines don’t employ huge numbers of people.

Larger mining firms will argue that artisanal mining is dangerous, unhealthy and that small-scale miners like Mwamba and Kikungwe are exploited in places like Manono by traders, who undercut them on pricing. After all, the large firms argue, they pay hefty taxes and royalties to the government, which should use the money for public works. The problem is that the money is often stolen by politicians in Kinshasa before it can return to the local communities. AVZ’s solution to this impasse, Brown told me, is working with the local community to build essential services, like schools and hospitals. AVZ would probably, however, be able to exert little control on the continuity of such projects if they sell their stake.

At Roche Dure, a series of steps had been cut back in the ground – Belgian or perhaps Mobutist earthworks from years and years ago. Around the edge of the gigantic hole in the ground (for that is what mines end up being), manioc roots had been laid to dry, sliced in half.

‘That’s pegmatite,’ Brown said, showing me samples extracted by AVZ, virtually worthless in such small quantities, but indicative of a far greater wealth beneath.

The tour ended with Brown taking me round to a series of bore holes, from which AVZ extracted its core samples, or assays. They were lain out in a large shed nearby. Scientists had long known that Manono had a huge lithium reserve, but AVZ was the first to put the effort into proving its profitability.

AVZ was established in 2007 as Avonlea Minerals, Ltd. For its first years, Avonlea focused on iron ore and vanadium mining in Namibia. In 2012 the company changed its name to AVZ Minerals. Its new managing director was Klaus Eckhof, a German geologist who had contacts in Congo: in 2003 he began exploration at the huge Moto gold mine in the northeastern corner of the country. (Eckhof would later leave the company under a cloud and claim that AVZ’s executives were, as he put it, ‘racist’ towards their Congolese colleagues.) In 2017, AVZ issued an announcement that it had made a deal to acquire the rights to explore and mine Manono’s lithium deposits.

AVZ had acquired the mining rights from a firm called Dathomir, which is named after an obscure planet infested by evil witches in the Star Wars series. Dathomir in turn had acquired the rights to mine Manono the year before for $6 million, which AVZ promised to pay along with the shares. (The investigative nonprofit Global Witness estimates that Dathomir earned up to $28 million for, essentially, flipping the mine.) Dathomir was partly owned by Guy Loando Mboyo, a thirty-something Congolese lawyer who reportedly had close ties to Congo’s then-president, Joseph Kabila Kabange. Loando was the son of two teachers from central Congo who had grown up in what he once described as a ‘modest family that was rich in love and principles’. In the early 2000s, after his father’s death, Loando came to Kinshasa and studied law, creeping his way into the Kabila government’s power structure. (He was inspired, he claimed, by the principle of ‘working one’s way upwards’.) In 2017, he joined AVZ’s board as Dathomir’s representative and then resigned when he became a senator in 2019 and later a minister in president Tshisekedi’s government.

The majority ownership of Dathomir belonged to a Chinese businessman named Cong Mao Huai, known to most people as Simon Cong. Loando liked to describe Cong as a kind of mentor. A one-time translator who came to Congo with close to nothing, Cong has over the last thirty years built up a portfolio of businesses in Congo, some in mining and others in road construction, though the jewel in the crown is the Fleuve Congo, a luxury Kinshasa hotel that Le Monde once called ‘the antechamber of power’.

A series of investigations called Congo Hold Up, which were coordinated by European Investigative Collaborations, a transnational journalism nonprofit, showed that Cong and Loando were involved in funneling money from Chinese businesses, including mining concerns, to president Kabila. At least one firm, the China Constructions Corporation, listed the Fleuve Congo hotel as its Kinshasa headquarters.

AVZ published the results of its assays in a series of announcements on the Australian Securities Exchange in 2018 and 2019. The tone was breathless: ‘Remarkable Drill Results Confirm Carriere de l’Este Prospect as an Additional Potentially Massive World Class Lithium Project to Rival the Roche Dure Deposit.’ The lithium world was set abuzz. ‘Our total resource is 400 million tonnes at 1.6 percent lithium, total strike length is about thirteen kilometres long,’ Brown says as we tour the site.

Chinese companies were quick to try and work with AVZ. Within a couple of months, a company called Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Co., which buys hand-mined cobalt in mines to the south of Manono and has been accused of abetting human rights abuses and child labor, had signed an agreement with AVZ. Then, in September 2021, AVZ signed a $250 million agreement with a company affiliated with CATL, the world’s largest electric vehicle battery maker.

A US State Department official expressed concern to me that the Manono project would give China even more control over the supply chain for energy storage. Xi Jinping, China’s president, has prioritised the electric vehicle industry, and China’s largest battery firms, buoyed by state infusions of capital, have stepped up to the task; China now accounts for 60 percent of global electric vehicle sales.

Battery makers need to assure safe sources of minerals like lithium for the future. CATL arguably went the furthest of any such company in its search for cobalt, another battery metal, when it bought a $137.5 million stake in the Kisanfu mine, to the south of Manono. The US government, on the other hand, is ‘playing catchup’, the State Department official said, and told me there are no US businesses in Congo apart from a Coca Cola bottling plant. A Washington lobbyist told me that the US government does not help investors who want to buy stakes in mines in Congo, despite overtures from the Biden administration about ‘critical minerals’. Businesses from the US and Europe have to contend with anticorruption legislation, which also exists in China, but only seems to be applied very sparingly to Chinese firms working in Congo.

At Roche Dure, Brown said, the ‘proven reserve’, that is, the amount of rock that AVZ knows is in the ground, is 130 million tonnes. The mine life will be about twenty-nine years. A Congolese state-owned enterprise, La Congolaise d’Exploitation Minière, or Cominière, owns 30 percent of the mining company. Whatever lithium is mined will also be taxed at 10 percent, as it falls under Congo’s mining code for ‘strategic minerals’. Under the legislation, mining companies have to commit to building amenities for the local population. (In a 2021 report, the advocacy organisation Global Witness criticised AVZ for not releasing its environmental impact plan in a timely manner, and expressed concerns it had not yet fully laid out its plans for its work in the local community.) Brown and others at AVZ pointed to plans for a hospital and a school that were already underway. In early 2022 the company’s valuation on the Australian Securities Exchange reached 4.6 billion Australian dollars (around $3.46 billion at the time).

But even as we talked, moves were being made in Kinshasa to block AVZ’s Congolese entity from continuing the project. A member of Tshisekedi’s inner circle had taken a personal interest in the project, and she had been involved with the sale of the Congolese stake to a Chinese firm called Ziijn Mining. Lisette Kabanga Tshibwabwa has family ties to the president’s home province, and is part of an ascendancy of people with such connections who have taken the reigns of power. According to a report by the Congolese Inspector General of Finances, Kabanga was paid $1.6 million by Zijin, just before Cominière sold half of its shares – 15 percent of the entire project – to Zijin.

AVZ was caught off guard: the company’s executives said they thought they had the right of first refusal over the sale of Cominière sales. Zijin started to move against AVZ, and soon their license was revoked. The company’s value started to plummet on the Australian stock exchange before trading of the stock was suspended pending resolution of the dispute. Lawsuits were begun: Zijin sued AVZ for $850 million, and AVZ took Zijin to arbitration court in Paris. In a September 2023 press release, the firm’s representatives said they believed that Zijin, Dathomir and Cominière were ‘acting in concert to crystalise disputes with AVZ and disrupt and delay the development of the Manono Project with the aim of seizing control of the Manono Project. Their conduct has contributed to the delay by the DRC’ – Congo – ‘in granting the exploitation permit.’ The project stalled.

At his home in Manono, Pierre Mukamba Kaseya, the government administrator of the region, looked at me through rheumy eyes. He wore a white T-shirt and flip-flops. Mukamba told me that I was the first journalist to come to him and ask about the town in years. I couldn’t tell if he was just being polite. His white, modernist home was dilapidated, and behind him hung a poster commemorating Congo’s leaders – Lumumba, Mobutu, Kabila, but also Moise Tshombe, who led Katanga’s separatist government in the early 1960s.

Mukamba was pensive, but when I described my Greek origins, he brightened a little. ‘You must, as a journalist, help Manono, help put us on the map again. Show the crisis and how people suffer.’ The crisis he was referring to was Manono’s general dilapidation and poverty. Mukamba died last year.

Last November, a report by Global Witness intimated that the old colonial paradigm risks being repeated in Manono, which is certainly one possibility: outsiders get rich, and local people are left with holes in the ground. Or as the report puts it, ‘shell companies profit while Congolese citizens wait for change.’ But the townsfolk are also desperate for services and for infrastructure, and their numbers are growing. Lithium could allow them to develop the area, just as China has done with its shiny, new rare-earth mining cities. With the lithium project stalled, Manono is, in Kazadi’s phrase, ‘left to its own bad luck’. Roads flood, elephants trample crops, food remains hard to come by for many families and preventable diseases like polio spread in the absence of healthcare. The questions surrounding how to balance development with an expanding population remain unanswered.

The Australo-Chinese lithium squabble is still caught up in the courts – no AVZ representative would speak to me for this article, and when I tried to attend a hearing between the parties at the International Chamber of Commerce’s International Court of Arbitration, in Paris, I was told that such proceedings are secret. Graeme Johnston, the technical director for AVZ, declined to be interviewed but he did send me a series of emails. In his last message, he wrote that the Chinese firms trying to wrest control of the Manono lithium concession were ‘a bunch of gangsters’. The cases were in court, he said. ‘We are facing a concerted and well-funded disinformation campaign in the DRC paid for by our Chinese mates,’ he continued. He ended with a geopolitical kicker, the type of thing that the State Department officer had been so concerned with when we spoke. ‘Since this deposit could supply 20 percent of the global lithium supply it is logical to assume that those who end up with Manono will be able to control the world’s lithium price.’

Leaving Manono, I managed to book a seat on a flight that AVZ had chartered from the town’s small airstrip for Brown’s departure. Taking off, Brown and I looked down at the town. He showed me where AVZ planned to build the new hospital and a new power plant, that was, if AVZ stuck around long enough to start extracting Manono’s lithium. The city was elongated along boulevards; from a distance, the houses looked neat and new. We banked southwards and gained altitude. For a second, I saw the mines: two giant holes in the ground, ready to swallow the city whole.

Photography courtesy of the author