We were gathered on the South Bank, next to the Royal Festival Hall, myself, the head of the small publishing company, his wife, and several thousand other participants in the arts, to celebrate the biennial Festival of Culture. Our formation of three was positioned close to the heart of the Literature Zone, adjacent to both the Theatre and Performance Zone, centred around the King George Hall, a hundred metres or so to the east, and the Visual Arts Zone, using as its base of operations the Hayward Gallery, which stood within eyeshot, through a crush of stairways and mezzanines set back from the river – it was in that direction that Genia Friend and her companion, the South African coffee-bean roaster, had disappeared. Hordes of people of all ages, enthusiasts and producers of culture both, moved through this scene at a dazed pace, taking their positions at pastel-coloured tables and chairs, where they drank coffees, teas, beer, juices and shakes, or ate tacos, hotdogs, soufflé pancakes, banh mi and bento from biodegradable packaging. Festival of Culture was here. A blimp turned faithfully overhead, with the new logo on it. There was some truth, I reflected, in the head of the small publishing company’s earlier statement, that a crisis of confidence had emerged, here in the heart of the Literature Zone, so to speak, over the past couple of years: that a fever, felt only at the fringes to begin with, had swept in from those marginal, outlying territories of the art form, populated by antagonists and outcasts whose theories occasionally gained low-level support before being pitilessly extinguished by the rational majority – but in this instance the idea, or feeling, had taken hold, and gone on to infect the industry at large with a widespread, debilitating anxiety. This nervous mood had simmered away for months, increasing in potency, until it was reborn as a discreet but total state of alarm. Barely acknowledged within the sector’s working environments, it nonetheless had begun to exert a powerful, unseen influence on the day-to-day choices of its operatives. This heightened atmosphere was one of uncommunicated insecurity, even paranoia, meaning that beginning from the bottom, with the junior editors, slush pile readers, publisher’s assistants and reviewers for mid-circulation journals, belief in the established standards and practices of the industry had begun rapidly to wane – many literary agents and editors ceased, almost overnight in some cases, to vouch for their own judgements, and when these key negotiators turned for support to their colleagues and associates, or to such benchmarks as provided by their previous deals, or other trade success stories, which usually could be counted on to have a steadying effect, those cornerstones, rather than meeting them with reassurance and solidity, turned out to be entirely insubstantial, their elbows passed straight through, and down they went. Of course, these individuals, the assistant editors and up-and-coming junior agents, the interns and first readers, were confident young men and women, employed to an extent on the basis of their capacity for certainty, and products in many cases of elite educational institutions – if they trusted in anything at all it was in their own faculties and their ability to make judgements. They had always known what they were looking for, or they had known it when they saw it. But now a fissure of doubt had opened, and they were no longer certain they knew what they were looking for, whether they would recognise it when they saw it, or if they had missed it, and it had already passed them by. They began making tentative enquiries to their colleagues and associates, and were relieved to discover, having endured a certain amount of pretence, that their colleagues and associates found themselves in a similar predicament. It was simply not believable, they felt, that their gifts could have deserted them – the fault must lie, they felt, when they met to talk about this, as they began to, on high stools at city pubs after work, sliding their microbrews and almost spherical glasses of wine agitatedly on the table tops, with the material itself. The problem had to be with the material they were handling, they decided something had changed, something fundamental – and so they passed it on: they passed it up, in other words, to higher stations, to the floors above, the inboxes of senior editors, to offices with tall windows and views of the grey and green squares of the city, to persons whose names were debossed on paperwork and on metallic signs above the brown brick doorways. They knew that the owners and senior actors of these companies were not as self-assured as was widely believed – they appeared that way when they were glimpsed in the windows of a restaurant, having one of their famous lunches, or lifting a pen behind an antique desk, but in reality much was projection, much was illusion. The circumstances of these appointments were labyrinthine, concerning many disparate, interested and invested parties, the result of delicate, shadowy calibrations, and frequently passage to those high-ceilinged offices did not lead through broad daylight. Once their junior staff, tier by tier, had begun to furtively evade responsibility in the decision-making process, which often required only a touch of finessing at the final stage, once deprived of those systems of consensus, whose key posts they started to find unresponsive at the moment they appealed to them, many of those at the pinnacles of these companies panicked. A flurry of rash decisions followed – some stalled, entering a state of paralysis from which they didn’t emerge, even as the floors below them descended into chaos; others attempted to deflect the blame, and became ensnared before long by their own duplicity; still others embarked on strategies to protect the public face of their interests, and insisted in all dealings on presenting the semblance of control. It was this last tactic that led to the worst disasters, in the form of a series of discoveries, staggered over two or three weeks in the spring, during which the story dominated all platforms as it entered an annihilating spiral that was willed to completion by various orders of the commentariat, that two of the main commercial houses had been proven to have released several fixed books, that is, to have sold, as new, publications that were revealed to be reprints of earlier publications, with minimal changes implemented to disguise this fact. Typically locations and names were switched, titles and authors were of course replaced, while the rest of the content and structure remained intact. The supposedly culpable parties, when they were unearthed in their buildings, admitted before the banks of media that they had undertaken this admittedly extreme and reckless course of action only to tide things over, while the market endured its most troubled and unpredictable period in recent history. These hastily summoned apologists, with their calm willingness to shoulder the blame, were regarded as unconvincing and inadequate sacrificial offerings by most onlookers, and so, on an unforeseen scale, every aspect of the industry’s architecture came under intense scrutiny; every major player in the field received challenges to redress and redesign, as shockwaves moved up and down the once proud edifices of publishing, shaking loose careers and reputations. Heads, like they say, began to roll – the heads of the highest-paid agents, for example, and the heads of company heads – heads fell from the windows of the Big Four – from the top of the tree, for weeks, it rained heads. Finally, those that were left in the emptied towers of the once great houses began to regroup, to organise themselves. They met after dark in curtained rooms, for hour after hour, and eventually they mounted their response. The reading public – they wrote in a collection of statements, echoing each other, and released simultaneously by representatives of all the implicated bodies – the reading public was exhausted and frustrated by the whole affair, they were bored, in fact, by the tiresome continuation of the crisis beyond a point that was meaningful or helpful. Terrible mistakes had been made, but it was now time to draw a line under this regrettable period and to start afresh. For that to happen, in a way that would begin to rebuild the reading public’s trust, to allow them to read with confidence, certain of the industry’s integrity, measures had to be taken. What they proposed was this. They – and by ‘they’, they meant a panel selected by a coalition of the main publishing houses’ PR departments – had been working in collaboration with a team of software engineers on a technological solution to the crisis. The team of engineers was nearing the completion of a program that they – the select panel – believed would have wonderful, recuperating effects on the devastated marketplace. Working from the latest developments in plagiarism detection services, the team of engineers had constructed a tool that made all previous plagiarism detection services resemble child’s play sets – that was the claim. Not only would this program be able to recognise and match any extended sequence of words and phrases in the submitted document with those contained in an existing publication, but, using quantitative analysis and comparison of a sophistication hitherto not imagined, it would be possible to identify such features as the machinations of plot, the structural dynamics of narrative and perspective, the balancing of metaphor and the density of descriptive language, tactics of rhetoric such as repetition, assonance, anaphora and apostrophe, the intersecting arcs of major and minor characters and the patterns of their outcomes, the pacing and delivery of dialogue, the physical laws of fantastic worlds, chronological distortions, and even the biologies of imaginary creatures. They also had in their sights that most elusive quality, the style of the work, which would be objectively defined at last, locked down, taking into account the frequency and emphasis of specific words, the frequency and emphasis of specific sounds, and perhaps even – the engineers refused for now to be drawn on this point – the indivisible emotional components, below the surface, underpinning everything. So that what the program would arrive at, by logging all of these variables and myriad others, over a plethora of categories and sub-categories, was a complete taxonomy of every literary publication in the language, graphed every which way, testable through any metric, readable along any axis, displayed in colour-coded charts or sharp monotone grids, as the viewer preferred. A friendly dialogue between two sworn enemies. Business failure prompting a descent into criminality. Children who die in the first twenty pages. Descriptions of the light in western Scotland. Easter as the story’s climactic and final date. Friendships resulting from traffic accidents. Giant plants. Historical figures cross-dressing. Isolated pieces of luck. Junkyards as hideouts. The knocking out of the narrator by an unknown assailant. Lavish descriptions of feasts. Mythical creatures malevolent in appearance yet well intentioned. Northern European cities as honeymoon destinations. Open wounds infested with maggots. Purple garments. Questions directed to an artificial intelligence. Risky bridge captures. Sex in bathrooms. The betrayal of a king by his nephew. Uses of time travel to investigate ambiguous parentage. Visions of the Christ child. Worlds with three or more moons. Xenophobic shopkeepers. Yellow-haired villains. Zoo as principal setting. And so on. We are able to apprehend, the statement continued, for the first time, an absolutely individual fingerprint, the soul of the book, and with this wonderful tool we will strive to ensure that no work is brought before the paying public that runs the risk of being exposed as a sham, a copy, on any level a fraudulent document. This kind of deception is at an end, the originality of the author enshrined, placed once again at the centre of the enterprise which we each still live to serve. Signed, yours faithfully, etc. Further to this grandiose announcement, the replacement heads of the large publishing companies, in their wisdom, opted to house their plagiarism detection program, or a visual representation thereof, in a highly visible city location, in fact on the site of some disused cash machines along the Strand, making it a kind of monument: a reflective metal globe with serrated discs, lit up inside a glass box, to serve as a reminder, they said in the press release, for the industry and all its employees. The effects of this were easy to predict, and indeed were predicted by many invested outlets and individual commentators – having gathered up the blame, the strange nervousness and fear of that time, as if into a dark cloud of apocalyptic width, the old houses and agencies were now able to cast it down, like rain, upon the authors. The uproar was immediate. Criticism and condemnation rose on all sides. The new measures meant authors would be punished for the mistakes of the publishers. Authors were to be made scapegoats for the incompetence of editors. Authors would be victimised by this rigorous programme of testing, while the industry evaded responsibility. Piece after piece was written on this theme, the plight of the authors. But the data analysts were not as clunky or literal in their endeavours as many would have guessed. They had anticipated the reaction and were ready with their counter-argument – a manuscript, they said, would not be purged by publishing’s new oracle for simply quoting an existing work, obviously. Neither would it be penalised for making use of the deep structures of a mythological source, or the rhyme scheme of a forgotten poem, or deploying many of the popular devices of literature widely considered available for use – choices that no lawyer versed sensibly in copyright law would be willing to prosecute. This had all been factored into the programming. Anyway, it was clearly not in their interests to seize up literary production for any longer than necessary. An agreement was reached that a submitted document must achieve a score of ninety-six per cent or more, across its listed categories, in order to qualify as unacceptably derivative. This sounded high to everyone, and was duly confirmed as the new industry standard.

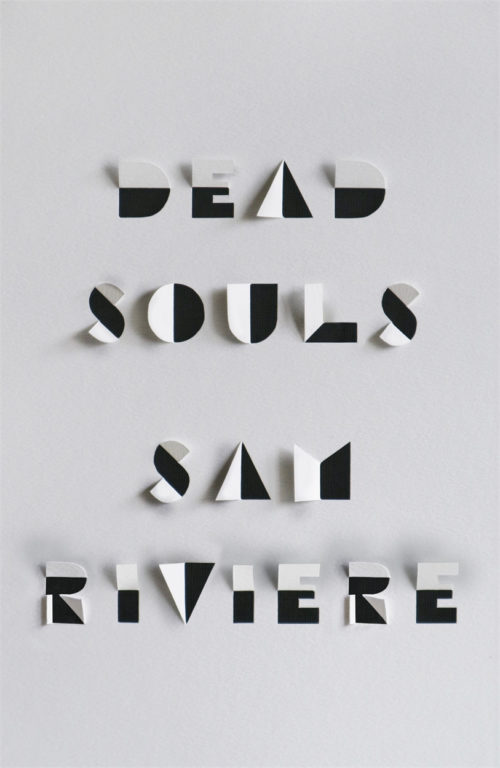

This is an excerpt from Dead Souls by Sam Riviere, out with Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Image © Alexei Schwab