It’s been three days since our mother died. Her name was Nasfa, and that’s all we’ve ever called her. There are three of us, in a compartment on a train making its way through Germany, to Hungary. On the floor between our seats is the narrow coffin in which Nasfa lies.

The train has called at Bad Iburg Station in the Teutoburg Forest.

I carve my brothers’ names into the windowpane with the rusty pocketknife Nasfa once gave me: Miska and Jakub. They’re asleep in their seats across from me. The station is made of red bricks. Many of the tracks are covered by big, gleaming puddles that ripple in the wind. The water trickles onwards, across the thistles and grass peeking up.

I want to get out of this train, Jakub wakes up and declares. No, please stay, I beg. We have to guard the coffin. Both of my brothers scratch their brown beards.

Our red train starts up again. It’s night, but we can make out the dark green trees of the forest extending as far as the eye can see. At another platform, an old, brown train starts with a shriek, and water from the tracks splashes up across its rusty sides. Miska wakes up, too. There’s no point, he mumbles. Let’s get rid of the coffin! Bury Nasfa in the forest. Impossible, I whisper.

Nasfa is dead. I trace my brothers’ carved names in the window with my nail: Miska and Jakub. The train is nearly empty. We’re headed for Eastern Europe, to the home of our mother’s ancestors. Our plan is to bury the coffin in Köbölkút, the village in Hungary where Nasfa’s family came from. We’ve never known Russia nor Hungary, only heard about the deportations and wars.

When Nasfa told us about the deportations, we would reenact them afterwards. She would sigh and bury her face in her hands, and we would feel exiled, just like she had been. She had heard stories of Hungary every day when exiled in Russia, where she and her Hungarian parents, relatives and friends all felt like strangers. Later on, Nasfa and her parents had returned to Hungary, only to flee the country for good after the Russian invasion. Only Nasfa had survived the flight.

When Miska, Jakub and I were children, we would look out at the rosehip and dandelions in our garden, and even though we were free and had lived our entire lives in this house with the garden, we too felt trapped, estranged and exiled.

We don’t belong here; we don’t belong anywhere, Nasfa would often tell us. And we too felt as though we belonged nowhere. Sooner or later, we’ll go home, Nasfa said.

Once, as I lay on a fallen tree in the wheat fields amidst the vast, silent landscape, I had tried to imagine my mother’s relatives, under fire by the Russians during the deportation from their hometown long ago. Nasfa’s family had been forced to bury several of their friends along the way, but the soldiers had ordered them onwards, threatening to shoot them if they didn’t hurry up, and then shot at them anyway, even when they did pick up the pace.

Now Nasfa is lying in a coffin in our compartment. The train is headed for Hungary.

The train has stopped at Hannover station. There’s a faint stench of rot from the stagnant water covering the tracks. All this stopping is driving me mad, says Jakub. I can’t take it any more.

Those were the words Miska had said just before Nasfa passed away. In the end, her breath had been so raspy and she was so clearly suffering that Miska, after listening to her sickly breathing for a while, declared: I can’t take it any more. Then Nasfa let out her last breath, and he cried: Come back!

Miska and Jakub stare out of the window. The train has travelled a short distance only to come to a halt yet again. The darkness makes it hard to see what’s going on outside, but we hear the screech of wheels and voices shouting in German. The hum of a machine that probably sucks up water, and a chemical fume, which is spreading.

I brush my hair. Miska and Jakub don’t understand why I want to keep myself from deteriorating. The train starts up again. Every so often I’ll think it has started to snow outside, but it’s only the sparks from the glimmering tracks. We boarded this old train together all the way back in Hamburg. Some of the compartments are big enough to fit a coffin.

One of my brothers cracks his fingers beneath the blanket. The train stops at Magdeburg station. The platform is deserted. Only thistles and tall grass between the rails, and next to us, a high-speed train that looks new but can’t continue due to the water covering the tracks.

When we first set out on our journey, Nasfa was in this compartment, travelling with us to Hungary, the country where her parents were born and later deported from. Then the train stopped for two days, and she got sick and died.

The floor of our compartment is still wet after a flood in central Europe. I tell stories about Nasfa with my feet on the towels we’ve laid out. Once a day I go to the toilet to empty myself. I vomit, too. We eat fermented foods from jars. Childhood rushes by like a breeze. They’re asleep, my brothers. We’re approaching Leipzig. I put up my hair with one of Nasfa’s hair clips.

The train starts to move again. It’s about time. I can’t let myself sleep, because it’s my duty to keep watch over my brothers. I wash myself so I won’t smell. The air in our compartment tastes of iron, of old blood. The handles, the seats, the window. When we open the window, the stench of putrid water gets in from outside.

We’ve reached Leipzig. The station is enclosed in a dome of glass. Jakub, Miska, it’s Anna, your sister! Can you hear me in your sleep? Your fingers are getting so thin.

The train travels a short distance, then stops again. No one boards or alights. People wait with blankets draped around their shoulders, perhaps unable to continue their journeys. Through the window, we hear over the loudspeaker that several departures have been cancelled. The platforms are wet. Black puddles remain in some places. In the dim light of the tall lampposts, it’s hard to tell whether it’s water or oil.

I turn away from the window and look around: Our compartment has black walls, black lamps of chrome. The threadbare curtains still have a bluish tinge to them. The folding wooden tables are brown. Even the windowpane seems quiet here. The seats are weighty and calm, reticent and waiting.

I think they’re listening; Miska and Jakub. I tell them: If you think about it, Nasfa was in exile her entire life. The train screeches and sets into motion. Its heaving rhythm starts as a rumble beneath our feet.

Death is preferable to fascism, Nasfa often said. Each year, on the night of September twenty-fifth, Nasfa would hear a knock at the door. It must be visitors from Hungary, she’d exclaim.

The twenty-fifth is the commemoration day introduced recently, and much too late, to honour the deported Hungarians. Nasfa always hoped for visitors that day, but no one ever came.

We belong together, the four of us! Anna, Miska and Jakub and Nasfa. The train stops. The station in Dresden is also topped by an enormous glass dome, held aloft by arched columns.

Nasfa’s parents stored jars of fermented food in case they were ever forced to hide in the bunkers. Her mother had been preparing the fermented vegetables while she watched the Nazis invade their Hungarian village through the window. Later, when the Russians marched and raped their way through the streets, Nasfa’s mother had been making jam. Those in exile didn’t remember the Russians as liberators, they remembered them as ruthless animals. Russia was surely hell on earth.

The train is moving now.

We’ll get there eventually, I say. My brothers don’t hear me, they’re leaned against each other, dozing. I don’t mind, I’m used to it. They’ve slept almost the entire time since Nasfa died. There’s just a single pane of glass separating us and the clattering signs, clocks and blackened boards of the platform that glide past outside. The platform is dimly lit by torches. There must have been a power cut.

My brothers slumber on. Nasfa used to fear the day they’d grow up and turn into the men they’ve now become. She would sit by the window in her curry-coloured coat looking at pictures of Miska and Jakub as little boys.

Wrapping her coat more tightly around her, Nasfa had hissed: Men only think of power and acceptance. Her laugh was like a snowbell. Death is preferable to Nazism, she muttered grimly.

I don’t want to lose my mind. I forget so easily, I whisper into the compartment and draw my legs beneath me, because there isn’t room on the floor. The coffin takes up all the space in the middle of the compartment. In his sleep Miska stretches out his legs and rests them on top of the coffin.

My brothers ought to tame their beards and finish their food! They both have dirty plates on the little brown tables they’ve left unfolded. Let’s talk, I tell them. We have more long-life milk in the bag. I try to take care of them, but Miska kicks off his boots in his sleep. One lands on the lid of the coffin with a thud, the other falls to the floor. His socks are full of holes, his toes are bluish, and there’s nothing I can do about it. I fear that it isn’t just the cold, but a nascent disease caused by the rotting water on the compartment floor.

Soon we’ll bury Nasfa in Hungary, I loudly announce. Jakub complains of a headache. I’ve put on lipstick today, after forgetting the past few days. Nasfa always wore lipstick, no matter what. Dark red. Miska and Jakub are slumped against one another.

Childhood rushes by like a breeze: I see the thickets, the beech trees in the garden, and I recall the scent of apples, rosehip and dandelions. We were almost always outside playing in the tall grass, and when we came back inside the house, Nasfa would be staring out into the dusk and say: We Hungarians are always deported, our souls are always raped.

We did not understand the stories of her childhood in exile.

Our garden consisted of goutweed and dandelions, rosehip and old fruit trees, and it was full of weeds, which Nasfa insisted we let be. She said: We Hungarians are always purged, persecuted, denied our rights. Yanked up by the roots.

Now she’s in the coffin.

The train has stopped next to a pasture. Miska wakes up and looks around in bewilderment, and for the first time on our trip I don’t know where we are. There are no signs. Outside, the light is low. Miska peers out: Why have we stood still for so long?

Jakub is resting his feet on the coffin as if it were a footstool. It seems as though the train will never continue. I’m hungry and impatient for the train to start running, and I’m certain I smell petrol from the can beneath the seat.

It’s time you hear the truth, Jakub mumbles, but then he falls back asleep without another word.

Is it malicious of me to go on talking about Nasfa? The window is shut. It really does smell of petrol. Childhood rushes by like a breeze. My brothers blink their narrow eyes. Their hair is brown. I slip my hand into my right pocket and touch Nasfa’s medal. I sit quietly with my hand in my pocket, clasping the medal.

Listen, I tell them. Don’t go to sleep yet.

But they’ve already fallen asleep. We’re moving. The train rumbles along. It’s as though my brothers can no longer keep themselves awake for more than a few minutes at a time.

Remember when the train stopped for two days, and Nasfa sat upright in her seat the entire time, right until her death? I ask. Jakub’s lips are dark. Somewhere we are overheard and someone sets off in our direction, I think to myself.

Why do my brothers open their eyes so briefly only to close them again? Has the new year already begun? We’re a family travelling through Germany to Hungary. All I ask is that we arrive.

Nasfa knew all about the wars between the Russians, Germans, Hungarians. Who won and who believed that they won. Death is preferable to communism, she said.

While in exile, all the deported Hungarians, including her parents, would hide in cellars when the Russians came to Russify them. Nasfa did not fear the Russian soldiers who wanted to teach the exiled Hungarians to forget their country, to lie about their past and unlearn their mother tongue. Instead, she ran outside and sang Hungarian songs.

Remember, Miska, Jakub. I will continue to remind you. Nasfa did not fear the superior forces!

Let me tell you how Nasfa became a hero. She was only a child when she broke out of her parents’ cellar, strolled down the detested, dusty road in the exile town and spoke to the Russians who patrolled the streets. After that, people knew that she was the only one with the guts to tell the Russians about the little vegetable patch her parents once had in their garden, about the bunker and the jam and the church in their hometown in Hungary, which she could picture so vividly in her mind’s eye each morning, because she had heard stories of it since her earliest childhood. Nasfa berated those who had grown too comfortable in exile, and to the soldiers, she yelled: I curse Russia, and she accepted the beatings that came after.

Later, when we were children, she had refused to let the rebellion go. She would shout across the garden’s rosehip and dandelions: We’re leaving! We’ll tear down Europe’s barbed wire fences along the way. We’ll build a new city! We’re headed for better places. The only question is where. To Turkey? India? Canada?

Jakub shakes his head and closes his eyes.

Miska and Jakub wake up simultaneously: Good morning, Anna! Won’t you come outside with us? asks Jakub. Up into the mountains! Follow the hungry birds. We won’t be bothered by the floods up there. We’ve got to forget Nasfa! Find some people . . . Look, there’s smoke from a bonfire . . .

I bathe in their gazes. My brothers are truly awake, the both of them, with their eyes on me. Each night I think about going out and burying her some arbitrary place in Germany, Jakub continues. Giving up. We’ll never make it all the way to Hungary on this train, he says.

I look down at the compartment’s still-damp floor.

Remember, our mother was a hero to the Hungarians exiled in Russia, I rave euphorically.

But right now we’re in a compartment. Deep within Eastern Germany. Us three siblings, I say . . . Jakub stands up. No, he retorts. No, you’re wrong! Then, exhausted, he lets himself tumble back into his seat and falls asleep.

I can picture my brothers as two beautiful children. Bartholdy Miska, Bartholdy Jakub, boys in the thicket. In the garden, the scent of rosehip, always outside playing. Echoes when you shout in the forest. Reflections in the air. Summer days and Nasfa’s depression.

As we slowly make our way to Eastern Europe, I hear the sound of the wind in the fruit trees of our childhood garden, I think of crisp autumns and the darkness above the fields.

We can’t forget, I tell my brothers. Nasfa was an angel! How was it she walked? Bouncing. I stand up and bounce. Like this! She would clamber up the tree trunks when we went for walks and swing back and forth from big branches, I say. She would sing: I’m a human. If I die now, I’ll go to hell. Death is preferable to nationalism.

We can’t forget a single detail, I tell Miska and Jakub. We should all call each other Nasfa! Look, I still have her medal.

We’re approaching the Czech border.

Jakub stands up again. No, he says. Stop it. You want to know the truth? Nasfa was just another displaced person who didn’t resist. When the Russians marched through the streets, she hid, just like everyone else, he says. Nasfa died of shame because she never resisted! That’s what Jakub says.

I rummage in my pocket for the old photographs of Nasfa and us. Three heads of the same snake. Look at us! Her children, I say, handing him the photographs. Those pictures keep me alive. See the medal around her neck? It’s impossible to overlook. That was the medal she was given during the exile because she alone dared sing Hungarian songs in front of the soldiers.

Quiet, please, says Miska, I want to ring Nasfa’s phone. Just to hear her voice on the answering machine. Do you want to hear her, too? Miska asks. Jakub and I nod, and Jakub says: Why not? Miska looks at me, waits and sighs. But in the end he doesn’t call, just closes his eyes.

Nasfa used to sit at the station café drinking tea at eight in the morning, I say. With her lips pressed tightly together, she would remember the gauntlet run into exile. The elders who were shot down, the children who died of cold and starvation. She could sit that way for hours, recalling their faces, until she could no longer stand it and left without finishing her tea.

She was the kind of person who might sometimes beat the Russian soldiers with sticks and shout out the names of those who had died during the deportation, I say.

Jakub shakes his head. She hid from the soldiers when they marched through the streets, just like everyone else, he says. That was why she survived and why she died of shame. Later on. In this compartment.

I ignore him and try to sleep.

Good morning. My brothers are asleep again. I’ve spent the past few hours bowed over the coffin. We’re deteriorating, I say. We’re travelling through the Czech Republic. The few people waiting on the platforms look right through the train when we pass them. They despise us, I think. Stay with me, I say, Miska, Jakub. I’ll deteriorate if I don’t speak.

The West falsifies history, Nasfa used to sing. She would walk through the streets singing: Death is preferable to capitalism. We lost sight of her. Now she’s gone.

The train has stopped in Litomerice, the Czech Republic. It’s become colder, and the three of us have bundled ourselves up in blankets. Here there’s no rain and no flash floods. The station looks like a palace with its gilded lions and marble gates. In a thousand years, we’ll be discovered as four rocks, four fossils, and we’ll be alive inside those rocks. The world around us will have turned white. The darkness will have ceased. We’ll always be together. Miska, Jakub, Nasfa and me.

The same words keep coming back to me: Nasfa is dead. She’s in a coffin. We’re on the train to Köbölkút.

My brothers are asleep. I’ve run out of sleeping pills.

The train starts again. I put on lipstick. Miska opens his eyes and looks around. The compartment doesn’t move, but the train does. Jakub leans in close. She committed suicide out of shame, he says suddenly. She drank the petrol. That’s what happened. There’s nothing more to say. He squints his eyes. His beard has grown longer.

All those who deported us were men, Nasfa once told me over the phone. Russia, she yelled, where is that? It’s dead. America is dead. Scandinavia is dead. Man is dead. All that exists is the power of women.

The beard on Jakub’s chin makes me uneasy, even though I know that neither he nor Miska could ever harm anyone. Their beards simply grow, and they forget to trim them. How quickly the hair on their arms grows.

Miska and Jakub sit across from me, always the two of them. I wish my much too skinny, emaciated brother, Jakub, with his pasty skin and his body always slumped across the seat, would break into a smile on his distinctive face, just once.

Today is a glorious day, with bright light and snow.

Brno station.

I’d like to go outside. Just for a moment. I smile at the few passersby on the platform, but they seem to look right through the train, noticing only each other. They’re very tall, dressed in dark, elegant clothes, incessantly chattering. Then their figures vanish in the thick snow. I wrap myself in the beige wool scarf Nasfa gave me. It’s just past seven. Miska is reading a comic book. Outside, the birds squawk and flap about before landing on signs and lampposts.

The sun is already setting behind the station now. We got several hours of bright sun today! These days, it’s almost always dark outside. The train waits. The platform is well kept. The rubbish bins have gold fittings that gleam in the dim light. Two children in fur hats sit on a bench and stare straight ahead, seemingly oblivious to us inside the train.

Further off is the older part of the station. Here, the grass sticks up between the slabs. There are piles of bird droppings on the furthest benches and overflowing bins. A woman saunters past in high heels. A man with a newspaper under his arm and his black hat aslant walks beside her with his head turned away, talking into the air. Crowning the station is a small bronze dome, and at the very top, a blanket of snow. A silent plume of smoke escapes from a metal chimney. Dusk. Then complete darkness.

Four of us boarded the train together, Nasfa, Miska, Jakub and me, but only three of us will arrive. When Nasfa was still with us in the compartment, she whispered: I’ve wasted my time on men! Then she asked me to take care of the boys, Miska and Jakub. With tired, inscrutable eyes she watched her sons sleep and handed me the sleeping pills. We looked at each other. I closed my eyes for a moment and opened them again. She was still looking at me, clearly at a loss.

Later, her expression was simply closed. With resolve, she whispered: We’ve been at it for too long. Go to sleep. Here are more pills you can take when I’m gone, and soon you will grieve, just as I have grieved for most of my life.

I looked at her crumpled body, closed my hand around the pills and listened to her breath; I waited and waited, and she said: Now maybe I’ll be able to sleep.

Miska looks around the compartment and then picks up the photo of Nasfa, Miska, Jakub and me from the table. He studies the black-and-white picture for a long time and then slaps it back down on the table, hard. I think you ought to sleep now, he tells me. Staring out into the dark will make you sick. I tell him he looks the same as when he was little, and he strikes out at me limply and smiles. Your brown eyes look the same as when you were five, I laugh. It was your eyes Nasfa wanted least to leave behind in the world. Miska doesn’t reply. I turn away so as not to hear him snore tonight. He always snores. I put on my wool jumper over my dress. Pull the collar up to my ears.

Nasfa said: The disasters that befall you are always different than the ones you imagine.

I’m in the compartment with Miska and Jakub. Jakub is wearing his coat and scarf, moaning. He clutches his stomach and says the train journey gives him a stomach ache. If you disregard his bloated stomach, he looks like a little boy and an old man at the same time. A long evening and night lie ahead. The endless tracks. I cough. Miska stares at the coffin, his pupils are tiny and sharp.

It’s a tragedy, he suddenly says.

My entire body grows uneasy and my throat hurts. A biting wind slips in from the corridor. Jakub puts out his cigarette. I’ve put up my hair and done my makeup.

Let’s just go outside, Jakub urges and stands up. Stop it, Miska exclaims, grabbing hold of Jakub and forcing him to sit back down. There are people who have been expecting us for a long time. In Hungary! How will they recognise us? asks Jakub. Our mother was a child when she left the country, they’ve never seen her grown-up face.

Miska has closed his eyes and doesn’t answer. Instead he whistles softly with chapped lips. No one says anything. The moon is now visible in the sky. Jakub turns to each of us and laughs nervously on Miska’s behalf. It feels like spring.

The train ceaselessly pounds out the same, steady rhythm as we approach Bratislava. Miska stares with narrowed eyes at the treetops that appear in the distance. His eyes are even narrower than Nasfa’s.

Jakub takes off his wet socks. Anna, you always look like a boy in the pictures from back then, he suddenly declares.

I don’t respond and start to file my nails. The train is moving, but we are not. The three of us sit very still. I look at the coffin. An old coffin made of dark wood with a fluted lid, carved with butterflies, cherubs and vines. The only nice-looking coffin we managed to find while underway. Remember how one of Nasfa’s eyelids turned blue? I ask. Jakub pounds his fist on the coffin and hisses: Shut up!

What if the police at the border between Slovakia and Hungary confiscate the coffin with Nasfa in it? asks Miska. Don’t you think we ought to set it on fire instead? Right now? The compartment already smells of petrol.

Miska is right, the smell of petrol stings in my nostrils. Jakub looks out of the window without answering. With an abrupt movement, Miska pulls something out of his pocket.

I have a needle from Mother’s sewing kit, he says, showing us the old needle. Look, it’s dull. It was the only needle left, and Nasfa asked me to take care of it. Take this needle with you to Hungary, she told me, and put it in the sewing kit along with the other knick-knacks I brought with me from home.

Look how worn it is, Miska notes, examining the needle under the lamp. It’s not sharp at all any more, he says. And it’s rusty.

Why don’t we put the needle in the coffin instead? Jakub sounds defeated as he says it. Then he gives Miska a shove so he drops the needle.

The train halts with a shriek. Sirens can be heard from somewhere beyond the platform. The needle has disappeared beneath the seat. Miska lashes out at Jakub. You don’t believe in anything! I’ve had enough. A needle, Jakub laughs. A needle as a replacement for Nasfa?! You’re the one who’s gone mad from this train. Stop searching for that needle.

I lean in and tell them to go to sleep. They cover their ears with their hands and turn away.

Everything has gone quiet, but only briefly. Soon the wind starts to pick up. A gust sends newspapers and tin cans scraping across the platform. Here at the border between the Czech Republic and Slovakia, there is neither snow nor rain. Outside by the station a horse passes a carousel that has stopped spinning. A couple of men are setting up a travelling fairground. Jakub watches them as they work.

We can’t go outside any more. We have to guard Nasfa, I say. I’m tired of staring at the carrousel. It won’t be long before we cross the border to Hungary.

It’s no use, says Jakub and gets up. Let’s dump the coffin and go back to Germany. The Hungarian police will probably drag Mother out of the coffin anyway, Jakub complains. If I were any more sensible I’d hang myself!

If only Nasfa were here with us right now, Miska whispers. She was radiant.

Shhh, I whisper. Parts of Germany are already flooded. We can’t go back.

My youngest brother Miska’s clothes are now baggy. At this moment, his face is like Nasfa’s. They look more alike than usual; his face has become even narrower and his skin is darker than before. But it’s not just the two of them who look similar. In the photographs, it’s apparent that all four of us have similarities, but we only resemble Nasfa, as if we have only a mother, no father.

Let me tell you about Nasfa, yells Jakub and stands up. Nasfa wanted to get away! She wanted to sit down with her back to the world and paint. She drank petrol to kill herself.

I thank Jakub and ask him to calm down. The train stands still. The seats have springs. Someone is singing in the next compartment. Miska mumbles and goes on staring out of the window. The compartment is cold.

Someone in metal boots paces back and forth in the corridor. Jakub yells: Nasfa put up with the taste of petrol and went on drinking until she had drunk the entire can. That’s what happened! And then she went mad. That’s how it is. That’s how it goes. She drank petrol and went mad. She said: Just give up! The shame over wanting to survive in exile and hiding from the soldiers did it off with her, says Jakub. Shame catches up with you eventually, she whispered to me, and she was no exception. She doesn’t want us to remember her story. What she wants is for everything to be forgotten.

Jakub collapses. I give him a piece of cheese. Jakub shakes me: Anna, listen to me.

We’re still here, her three children, but we’re the ones being forgotten.

Jakub pretends to be dead. His body is splayed out across the seat, eyes closed, leg twitching. Men in boots march past in the corridor. A door is blown open. Early morning? Night? We’re the forgotten ones, Jakub repeats. But soon things will get even worse.

Nasfa was evil, says Jakub, looking straight at me. I don’t think I can do this any more. Shoot me, Anna. Shoot me, Miska. I can see a red spot in the white of his left eye. He looks very tired. Everything that once caused Nasfa to flee, he yells, that’s now happening in Hungary all over again. They’re shutting out foreigners. Let’s open the coffin.

It’s too late to open it, Jakub, says Miska.

The lid is screwed on, I say.

We stop at a town right before the Hungarian border. Snowflakes dust the quiet, empty landscape. Over the loudspeaker, an announcement is made in Czech. The train stands still for a long time. This time it’s probably the snow preventing the train from reaching the border. It’s no use any more, Jakub screams. I want out. Jakub jumps up and glares at us with wild eyes, then he runs out of the compartment.

Miska hasn’t budged for several minutes. He pulls something out from underneath his seat. The petrol can. Jakub is outside on the platform staring in at us. At first we were four, then three. Now there are two of us. The coffin reach Hungary. On the platform, Jakub holds his hand to his mouth and coughs. He looks like he’s freezing out there in the snow, wearing only his short coat. We have to stay inside. There’s a rattle from the train’s undercarriage. We watch Jakub stalk off across the snowy platform in a sullen farewell. Miska’s legs are trembling. I scratch my scalp, and my fingers become bloody. Miska lifts the petrol can with two hands and sets it down beside the coffin. Jakub has laid down on the platform. Now he stands back up and runs around like a ghost, snow in his hair and on his coat. Doesn’t wave. So he thinks Nasfa took her own life. That that was what happened.

A tree topples onto the platform. Jakub races off into the forest.

Now it’s just the two of us, Miska says. You and me, Anna. The train starts. I think of Nasfa going swimming in freezing temperatures, just to feel the sea. On the train, she had told us: I’ll die in this seat. She was sick. Now there are only two of us.

Miska has slept all night. We’ve been stopped at a new platform for hours. There are no signs here. Just a tall cliffside and ivy. Thicket and fog. A lush, green landscape. Are Miska’s toes frostbitten? I tuck Nasfa’s wool blanket around his feet. The train starts to move. The names of Hungarian towns flicker by: Gyór. Mint-green houses. Birch trees. Tatabánya. Palatial yellow buildings. Tall green fences and green telephone poles.

Outside on the platform is a dilapidated sign, half-buried in snow so only a few of its letters peek out. . . . Ö . . . Ú . . . Maybe we’re here, I tell Miska. Maybe we’ve reached Köbölkút. He closes his eyes.

The snow has stopped. The station is small. Just a single line of tracks glitters in the lamplight. I stand up. It’s practically pitch-black outside. Miska tries to get up too, but something seems to hold him down, and he shakes his head.

He hands me the matches and looks at me for a moment with narrowed eyes. Then he unscrews the lid of the petrol can and empties it onto the coffin. I can’t move. He takes the matchbox from my hand, pulls out a match and strikes it.

There are two of us in the compartment. We’re the same people as before, and the compartment is the same. But we alter the story around us. We’re our own funeral; two heads of the same snake.

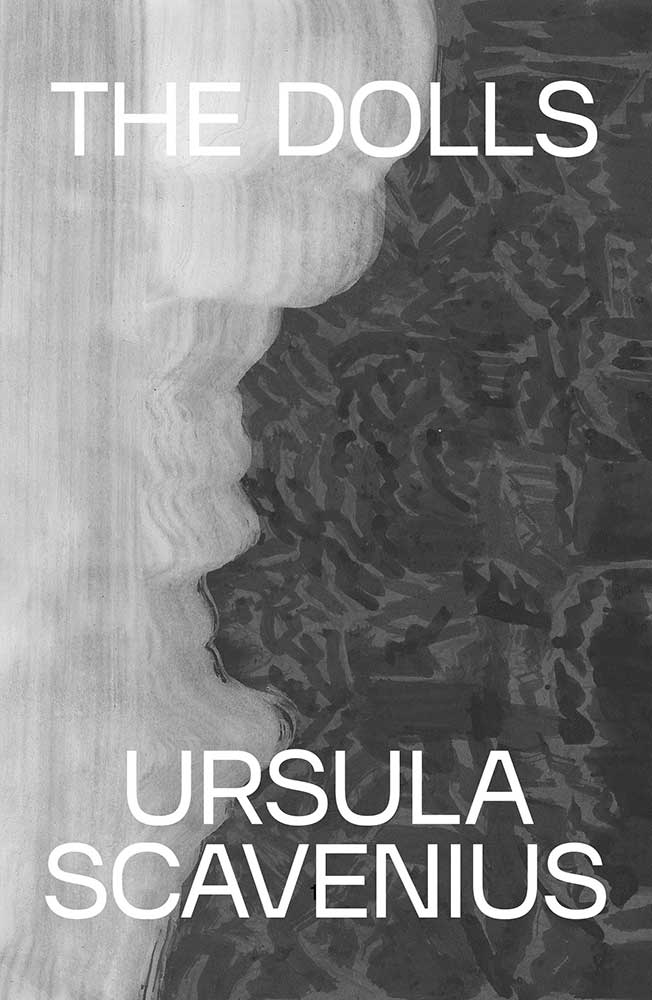

Image © Nikos Mouras

This is an excerpt from The Dolls by Ursula Scavenius, translated by Jennifer Russell, published by Lolli Editions.