The peelers had me down to the station at eleven o’clock on a Tuesday morning. They brought me into an interview room and questioned me about what happened that night I knocked your man out. They tried their best to catch me out, but I stuck to my story. I had been rehearsing it for days and was feeling good about how the whole thing was going until the man, the peeler man, who was the same peeler who had questioned me at the scene, whipped out a folder full of statements given by people who had witnessed the alleged assault and set them on the table in front of me. His wee blue peeler eyes locked on me as if to see how I would react.

He told me five witnesses had made statements against me, outlining an unprovoked attack on the victim, Daniel Jackson. This one from Gemma Hatfield said: Man about six foot tall, short black hair, well built, wearing a blue shirt, came up from behind Daniel and punched him in the face, knocking him unconscious. Another, from Kirsty Malone, said: He pushed me so hard I nearly fell and then he punched Daniel in the mouth. Daniel fell and hit his head on the ground . . . Joanna Porter said I was wearing a black jacket over my shirt and that I tried to hit Daniel’s mate after Daniel. Rachel Henderson said the same thing – they must’ve been mates – and Gareth Waters said I started fighting with him before I hit Daniel: I was outside trying to calm everything down and he started throwing punches at me. Daniel didn’t see him coming. He came from behind Daniel and hit him.

Daniel Jackson was still unconscious when the ambulance arrived. His statement said: I can’t remember what happened. I was standing with my hands in my pockets, then I woke up in hospital and there were nurses all around me. The report from the doctor on call that night said that the patient was knocked unconscious with a blow to the mouth: Mr Jackson suffered a deep laceration to the upper lip requiring musculature suture with absorbable sutures, and the overlying mucosal surface sutured with absorbable sutures. His lip was sliced open, and it was very likely that Mr Jackson would have significant facial scarring. The peeler held the pages up in front of me and said, The fact that Mr Jackson’s face has been cut and that the wound is as severe as it is means that the charge being brought against you is Assault with Actual Bodily Harm. Do you understand what this means?

I said I did, even though I didn’t.

Every one of them have given different statements, I said. They’ve all said things that didn’t happen, and not one of them has said a word about how Daniel Jackson and his mate came at me first.

The peeler leaned with his elbows on the table. Mr Maguire, it’s important for you to understand that this particular charge is for the assault on Daniel Jackson. Whatever happened in the lead-up to the incident is circumstantial, unless evidence can be given to prove otherwise.

Evidence?

Do you have any witnesses?

Maybe. I don’t know. I didn’t know anybody there.

I stepped out of the peeler station that afternoon feeling like I hadn’t seen daylight in days. I shielded my eyes with my hand and looked both ways before crossing the road to the bus stop. The bus pulled over and I stepped back to let the woman with the pram on first, then I treated myself to the front seat on the top deck. The view was great up there; I liked being able to look down at people going about their day without them knowing I was watching. For some reason, I thought about school. I thought about how I had tricked everyone into thinking I was hard, that I could handle myself, without ever having to throw a punch. I could wing bottles like a champion, and I was always getting into trouble with the teachers, and that somehow translated into me being able to have a dig. That’s how it worked at my school; tell the teacher to shove his Bunsen burner up his hole and everybody thinks you can scrap like fuck.

If kids started on me in the street I would run into my house and hide. I would stare out my bedroom window and pray for them to go away. Sometimes they did. Other times my ma would hand me a hurley and tell me to get stuck into them. I didn’t have it in me. My brothers saw this and did what they could to toughen me. They would trail me out on to the street and tell me to hit the kid I had to fight, and I would, because they were there and nobody had the balls to hit me back – my brothers had fought their whole lives and were good at fighting ‒ yet there I was, the only one out of the three of us who was stupid enough to get caught.

I got off the bus on Wellington Place and dandered around that side of town for a while, looking at stuff, thinking about things, but not paying much attention to where I was going until I found myself standing across the street from the clothes shop where Mairéad worked. I could see her at the front of the store, hanging clothes on the sale rail. She looked calm, peaceful even, the way she slipped each hanger under the hem, her hands working automatically, without conscious effort. I wondered if I should pretend I was going upstairs to the men’s section and bump into her accidentally on purpose. Instead, I messaged her: I’m in town if you’re about, and headed round to the bookshop.

I didn’t plan on stealing anything that day. I just went in for a look. Then I spotted a copy of Knut Hamsun’s Hunger. It had an introduction by Jo Nesbø, who I hadn’t read, and an afterword by Paul Auster, who I had. It seemed right up my street as well, anything that said ‘existential novel’ in the blurb was always a winner, and sure your man who wrote it won the Nobel; there was no way it was going to be shite. I slipped it under my arm and pretended to look for another book, and I really had to sell it. I had to make it look like I had already paid for the book I was carrying around so that if they were to catch me sauntering out the doors I could say, shit, sorry, I was in a world of my own there, and crack a joke like I had completely forgot. People do it all the time, and let’s be honest, nobody wants to phone the peelers. They don’t want to go through all that crap. They just want to get through their shift as quickly and painlessly as possible, with no aggro. No additional paperwork. The one thing I had going for me was that people walk in and out of bookshops with books in their hand all the time, and there ’s no way of telling who’s paid for what. The trick is to make it look natural, and the best way I could think of doing that was to stop right outside the doors and act like I was in no hurry to go anywhere. When I was sure that nobody was going to call me back into the shop, I sauntered on down the street with the book tucked under my arm.

People were on their lunch break. They sat out the front of the City Hall and watched the pigeons and the seagulls squabble over their crusts. I found a seat in the sun, on a bench facing away from the road, and read the first page of my new book. I hadn’t been able to get through more than a few pages of anything in months. But there was something about the sunshine and the heat and the crowds of people lying on the grass that appealed to that part of me that used to dander around Liverpool with a pocket-sized Moleskine journal tucked in the inside pocket of my coat. I had a lot of thoughts back then and I took them very seriously. Then I finished my degree and moved back home. I hadn’t written anything since.

Was that you standing outside my work?

I looked up but it was very bright, and even though I couldn’t see, I knew it was Mairéad. She had a big leather bag slung over her shoulder. Her wrist was bent all the way back.

You’re gonna get sunstroke, she said. Look at you.

There was a tree behind us with plenty of shade. We sat under there for a while, me with my back against the trunk, gulping from the bottle of water Mairéad had given me. She was wearing jeans with a black vest top. Her shoulders were sunburnt and she smelled like aloe vera. How’d you know where I worked? she said.

I didn’t. I was just walking past. I was gonna call in and say hello. So you just stood there like a creep, watching me?

I’m no creep. You were right at the front of the shop. Just don’t do it again, okay?

I held my right hand up to God. I’ll never walk past your shop again, I said.

Mairéad glared at me. You’re not even funny, she said.

I wasn’t going to tell her about the interview with the peelers, I didn’t know how she would take it, but I was nervous, and I didn’t know who else to talk to. She listened, and when I got to the part about hitting the lad outside that house party, she looked me dead in the eye and said, You’re an idiot. I asked why, and she said, I thought you would’ve wised up, I thought you would’ve knocked that shit on the head. I told her there was nothing I could do about it – two lads came at me, they were gonna knock my ballicks in, but she was sceptical. Not about whether or not I was telling the truth, but whether I was right to raise my hand the way I did.

Like, sitting here now, do you think hitting him was worth it? I thought for a second, then I said, Aye, I do.

Why?

Because fuck him, Mairéad. He came at me. Did he though?

Of course he did, why else would I hit him?

Mairéad didn’t answer. She watched a group of girls doing cartwheels on the grass. They wore leggings with crop tops that rode up their bellies as they spun. At the front gates, a fella in an Adidas top and cargo shorts had set up shop with a mic and a speaker and was shouting about sin and salvation. Two wee lads who were sitting on the bench closest to him stood up and walked away. They were holding hands.

The fucking state of it, Mairéad said, seeing what I had seen. I can’t wait to get out of this place, swear to God.

When do you go, right enough?

September, October. As soon as I’ve enough money, I’m gone. You nervous?

Mairéad laughed. Not at the question, but the way I had asked it. I’ll be all right, she said. I’ve a few mates over there. She picked a blade of grass and wrapped it round her finger. I don’t want to rely on them too much though. I want to make my own way, you know?

And then what? Then I’ll just breathe.

Across the way, the girls doing cartwheels were making eyes at a group of lads sitting close by. I glanced at Mairéad and saw that she was watching them too. She had this look like she remembered something, and for a second, it was like she had gone somewhere else.

Can you not breathe here? I said, and Mairéad shook her head. No, she said. I can’t.

She stretched her arms out in front of her and lay with her head back on the grass. She had worked forty hours that week, and she was selling shots again that night, from ten o’clock till two o’clock, then she was in the clothes shop first thing in the morning for a ten-hour shift her manager was making her cover for a girl who had phoned in sick.

I could do with a day off, she said.

I looked down at her and could see the freckles on her nose and cheeks. Above her lip, on the right side, she had a mark from a piercing she did herself with a needle and an ice cube. I asked if it was still open and she leaned on her elbow and said, Give me that bottle of water. She took a gulp but kept the water in her mouth and, using the air to push the water into the space between her front teeth and upper lip, spurted a little stream through the hole and across the grass, dribbling on my jeans.

Party trick, she said, and lay back down.

I went on Mairéad’s Facebook that night and looked at the photos she had been tagged in. Nights out in the Limelight and Stiff Kitten, the after-parties, the messy student houses down the Holylands where everybody’s taking Es and having a good time. Mairéad in the middle of it all as usual, slotting in with the kind of crowd she would’ve started fights with when we were kids. The hippies and the emos who stood out the front of the City Hall, listening to Nirvana. Cutting themselves. Calling people like me smicks and spides.

I scrolled down to the bottom of the page, back to Mairéad’s first few weeks at university, and realized I couldn’t go any further, that she had set up her profile when she had already moved out of Twinbrook and got rid of the tracksuit bottoms and the big gold earrings. Like this one picture I found of her standing in front of her wardrobe door mirror. She was wearing a pleated skirt with fishnet stockings. Her skirt was rolled up short, like when she went to school. It made me think about that day we were on the beek, years ago. I asked Mairéad if she wore knickers under her tights and she pulled her skirt up to show me. It was raining. We were standing round the back of the flats, in the alcove under the steps. She used her thumb to pull her tights down. There was a wee bow. Later, in my room, I had a wank over that wee bow. Then I got into bed and lay there for a long time, thinking about what I had done.

There was no word from the peelers, nothing about my statement or what they were going to do with it, until I got a phone call from my ma a few weeks later telling me there was a letter for me, from Courts and Tribunals. I knew by her voice that she had already opened it, and she knew I knew, but she still asked if she should read it.

It’s saying you’re up in court, Sean. It’s saying you’re the defendant.

Three days later, I was sitting in a solicitor’s office, a dusty little cupboard of a room taking up the floor above a hairdresser’s in Dunmurry. The man himself was a big fella, broad shouldered, with the kind of paunch that afflicts middle-aged men who don’t go to the gym as much as they used to but still cut an imposing figure.

Have you thought about your plea?

Not guilty, I said, and he looked doubtful.

I should tell you that if the verdict goes against your plea, your sentence will be more severe.

How much more severe?

It can be the difference between a suspended and a custodial sentence.

What like, jail? You serious?

He was. He told me to think very carefully about how many statements had been made against me and how extensive each of them was. The fact that every person who made a statement just so happened to be Daniel Jackson’s mate had nothing to do with it. When it came to court, it was their word against mine, and if there were five of them and one of me, the odds were stacked.

I tried to explain this to my ma, but she struggled to get her head around why anybody would press charges in the first place.

It was a bloody fight, what kind of person presses charges for a fight?

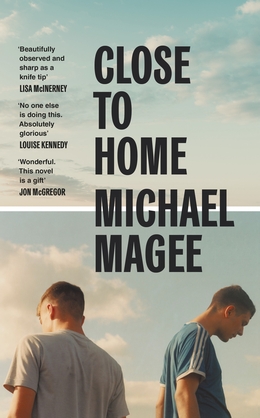

Image © Melinda Young Stuart