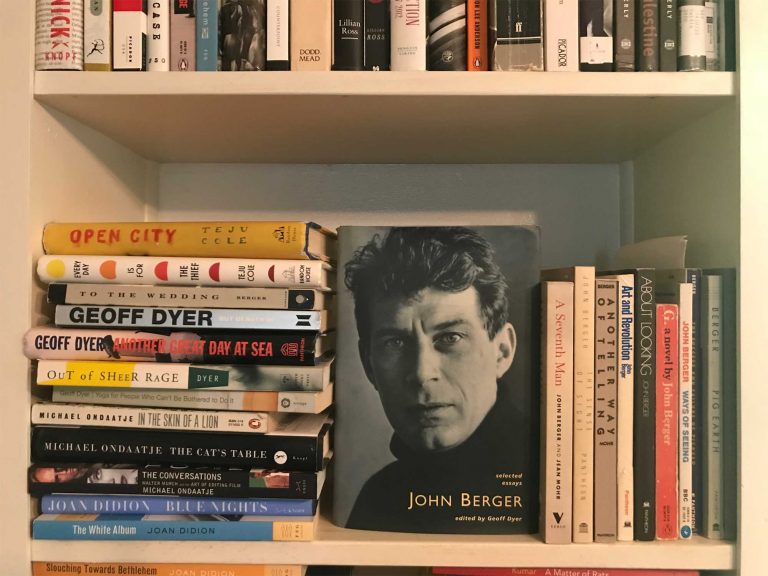

When I moved into the house I bought a few years ago across the road from Vassar College library, the first thing I unpacked was my own little library. On one small shelf I put books by John Berger, putting in the center an anthology of his writings, so that the photograph of a young Berger looked out on the room. Berger, at once a writer and an artist and a critic, was important to me: I had discovered him as an undergraduate in Delhi. No one else could be as political and sensual as he was in his writing. His books have been my companions for much of my adult life; A Seventh Man, his imaginative work on migrants in Europe, inspired my very first book, Passport Photos. His language hovered between poetry and criticism; he was at once incisive and lyrical; a precursor to many contemporary writers who mix genres. On that same shelf with Berger’s books I put books by writers I knew personally and admired – Michael Ondaatje, Geoff Dyer and Teju Cole – but also Joan Didion. I had never met Didion or Berger, so neither could be aware of this, but I had turned them into my mentors. ‘The contents of someone’s bookcase are part of his history, like an ancestral portrait,’ the critic Anatole Broyard wrote. I was trying to create a family album, accurate for who I was as a writer at that time in my life.

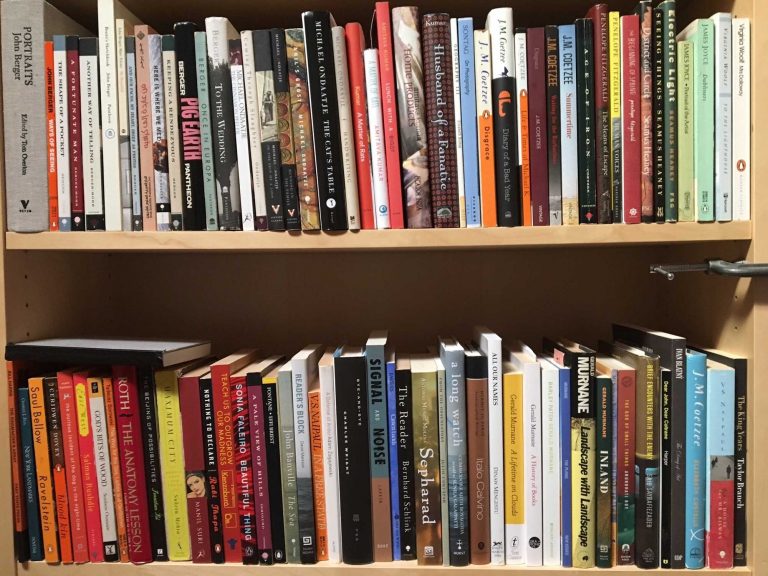

Bookshelf in my home with anthology of John Berger facing outwards

Bookshelf in my home with anthology of John Berger facing outwards

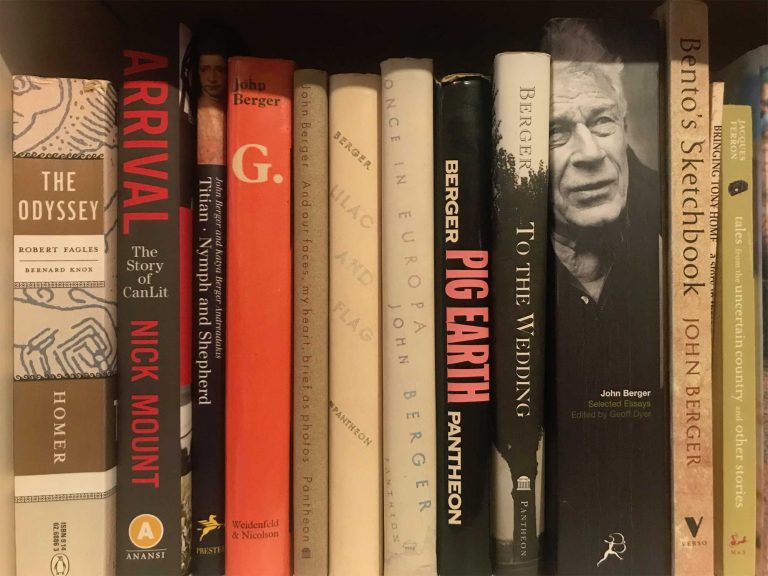

Recently, when I was on book tour in Canada, I asked Ondaatje to show me his Berger books in his Toronto home. I was seeking the family connection. Ondaatje said Berger’s work was scattered in different parts of the house but here were a few on a shelf. I hadn’t till then known of Berger’s Bento’s Sketchbook. It interested me at once – blood calling out to blood. Since then I have scarcely passed a day when I haven’t attempted to draw like Berger does in that book. Scattered among his meditations on Spinoza are his drawings of irises, plums, a bicycle, a sketch of a fifteenth-century painting of a crucifixion. I was touched by Berger’s attentive eye and his unaffected ease: wavering outlines drawn with pen and texture added by rubbing a finger wet with spit. This is what books we adopt as our ancestors do: they give you permission to carry on doing the same.

John Berger’s books in Michael Ondaatje’s home

John Berger’s books in Michael Ondaatje’s home

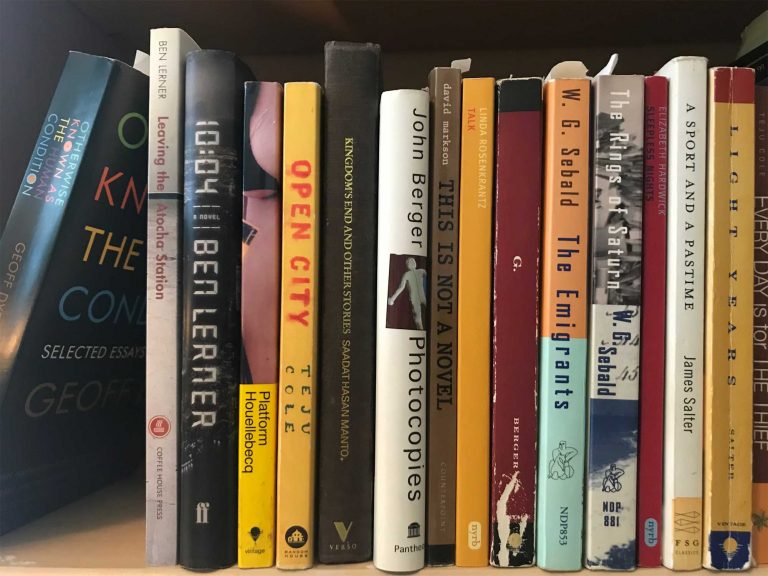

I unpacked Berger onto that little shelf four years ago, and in those years I began working in earnest on a work of fiction, a novel called Immigrant, Montana. My needs changed. The contours of the family arranged on the bookshelf shifted. I was still interested in making the reader see the world anew, the way Berger had made me do when looking at an image; now, however, I wanted examples from the realm of fiction. I was struck that for the kind of ‘in-between novel’ I wanted to write, I didn’t have to change the family picture too much. Berger was still there with his Booker Prize-winning novel G., but now Elizabeth Hardwick took one of the chairs at the front. I borrowed the opening lines of Sleepless Nights – ‘It is June. This is what I have decided to do with my life just now.’ – because it was June when I began writing my draft. Hardwick’s lines are in my novel. Salter is there for his sentences and the sex. And W.G. Sebald and Ben Lerner. Also, Renata Adler whose Speedboat is missing from the picture below but was definitely a model. I had written a short piece at that time with my rules for writing. Rule number six stated: ‘A bookshelf of your own. Choose one book, or five, but no more than ten, to guide you . . . ’ I noticed that I broke my own rule and chose more than ten books but can I say in my defense that I didn’t read a few of them? I put Houellebecq there thinking that my narrator would perhaps practice a perversely masculinist discourse for a bit, but his book didn’t hold my attention for more than a page or two.

A small bookshelf beside my desk while I was working on Immigrant, Montana

A small bookshelf beside my desk while I was working on Immigrant, Montana

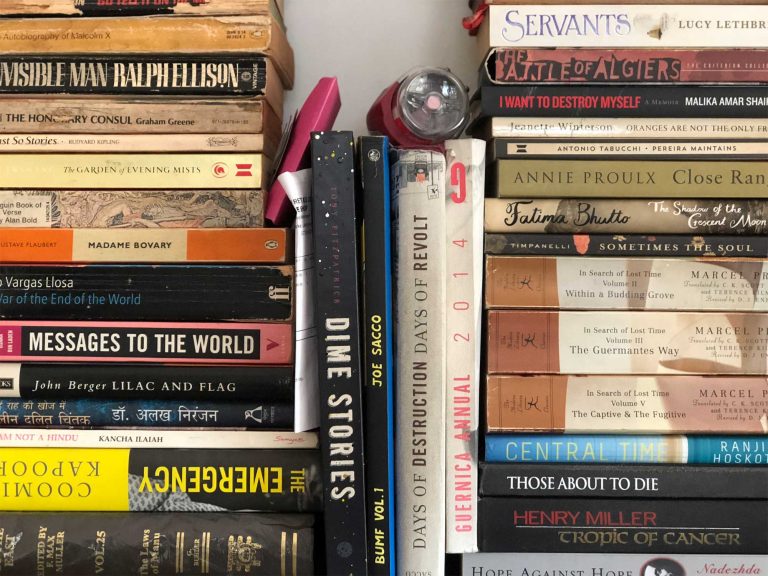

I’m using the metaphor of the family picture but what I’m after is something bigger. The world of books is so infinitely rich, any entry into it is a surprise. My point will become clearer when you look at the image of one of Arundhati Roy’s bookshelves: Malcolm X, Graham Greene, Rudyard Kipling, Gustave Flaubert, Mario Vargas Llosa, Annie Proulx, Jeanette Winterson, Marcel Proust. Such eclecticism! One of the titles on her shelf, Malika Amar Shaikh’s I Want to Destroy Myself, is one that I have been searching for the past three decades ever since I first read about it in V.S. Naipaul’s India: A Million Mutinies Now. If you look carefully, you can see a title by Berger, who was a dear friend of Roy’s, but what that book is surrounded by is all the uncontainable richness of the world, including a red flashlight and a VHS tape of The Battle of Algiers. Both Berger and The Battle of Algiers feature in my novel. In Photocopies, Berger had told the story of the youth of Pakistani radical thinker Eqbal Ahmad. I picked up that narrative thread in my novel and told the story of Ahmad’s adulthood, when he was indicted in 1972 for conspiring to kidnap Kissinger.

Books, a flashlight and a VHS tape on Arundhati Roy’s shelf

Books, a flashlight and a VHS tape on Arundhati Roy’s shelf

I have another photograph of a shelf with Berger’s books, one which predates all the other photos I have shared so far. It is a picture I took in Teju Cole’s home when he was living in Brooklyn. On the shelf with Berger, there is, expectedly, Ondaatje. But also, and this was the surprise and satisfaction for me, there are my books. I quietly clicked the picture on my phone. Why? Sylvia Plath has a line somewhere: ‘The worst enemy to creativity is self-doubt.’

Bookshelves in Teju Cole’s study

Bookshelves in Teju Cole’s study

I have never before said this to Teju, who is my friend, but to find my earlier books on that shelf with Berger and other writers I admired was to be given the gift of courage. While I’m faintly ashamed and embarrassed to look for my own name when I enter a bookstore and yet – of course, I do – I cannot understate how much it meant to me to find myself, in another writer’s home, sharing a shelf with Berger. A much-quoted line from G. reads: ‘Never again shall a single story be told as though it were the only one.’ This has been read as a slogan for skepticism with regard to claims of universality. Books are not to be isolated or condemned to loneliness; they are never happier than when housed with carefully chosen members of their families.

All photographs courtesy of the author, except photograph of Arundhati Roy’s shelf, courtesy of A. Roy