First, a confession. I’ve been buying books by William Vollmann for almost twenty years. His work – the very fact that it exists – seems to have taken on a kind of totemistic personal significance. It’s a physical hymn to wild ambition and tireless inquiry; an archive of human investigation.

Owning his books, though, has not necessarily meant that I have read them. Each year I pick up a different tome, begin it, set it down. Each year Vollmann produces further works so enormous that they both deepen my admiration for him and solidify my paralysis when it comes to finding a place to begin. It’s not that his work isn’t engaging, it’s simply that it’s overwhelming. Wherever you begin, the scale of what remains to explore lends the act of reading an air of futility, even exhaustion.

This year, though, I put down a marker. Catching myself in the act of buying another volume of Vollmann, I told myself, this is it. No more paralysis, no more searching for the ‘perfect’ Vollmann work when clearly there is no such thing. I would sit down and read Vollmann. I would keep reading Vollmann until I felt I had got somewhere.

What followed was one of the most immersive, maddening, breathtaking and baffling reading experiences I can remember. Once I began reading Vollmann, it turned out I couldn’t stop. I began with the excellent primer, Expelled From Eden, then turned to the extraordinary Rainbow Stories, The Atlas, and Volume One of this year’s typically uncompromising two volume work on fossil fuels and climate disaster, Carbon Ideologies. And in the middle of the year, as America descended even deeper into cruel and terrifying nationalism, I read what for me is at least one of Vollmann’s inarguable, lasting masterpieces: Imperial.

To say Imperial is ‘about’ the US–Mexico border is entirely inadequate. It may be focused on that particular stretch of contested and viciously defended territory, but the subjects it takes into view in its attempt to understand that territory feel near-infinite. To make one’s way through this book is to feel wholly and fully immersed both in the awful, crushing complexity of the world and in the brutal collective delusion that is contemporary capitalism and nationalism. It is to begin to understand how a simple ideal of self-sufficient farming morphed into an agri-industrial nightmare. It is to follow, at a level of detail that is first numbing and then completely impossible to turn away from, the slow poisoning of the soil that results from modern-day irrigation-based farming. It is to watch entire rivers become polluted to the point that their toxicity is practically visible in the air around them. It is to understand, slowly but undeniably, that the very idea of a border, even the idea of a nation, is a violent delusion. It is to watch, horrified, as thousands of people lose their lives crossing what is essentially a mirage so that they can be part of a dream that is an even bigger mirage. Amidst the fog of information and history, it’s the details that haunt. Border guards patrolling migration routes often find a pile of clothes a few hundred yards before they find a naked corpse. This is because your skin swells when you dehydrate. Right before you die, you rip off all your clothes in discomfort.

Vollmann’s fundamental honesty as a non-fiction writer stems from the fact that he is always there, always conscious of his own gaze and the tragic impossibility of escaping it. He is often as interested in his own failures as he is in the things he actually finds out. One of Imperial’s best chapters details his frankly hopeless efforts to investigate the secretive factories that operate along the Mexican side of the border. Another takes time out from the wider project in order to mourn the dissolution of Vollmann’s romantic relationship while he explores the very land he’s writing about. Yet another meditates on Flaubert, on the significance not just of documenting a life, but of giving life to experience, and ends up making a passionate case for the importance of fiction alongside reportage. At one point, Vollmann even attempts to conceptualise the landscape using forms found in the paintings of Mark Rothko. He never quite says it, but he seems to be making a point: all borders are arbitrary. Just as we cannot accurately delineate the edges of an invented country, so too we can never find a neat edge to form, or the precise point at which one subject, one discipline, one project, one life, bleeds into another.

One of the over-arching themes of literary debate this year has been the ‘difficulty’ of certain texts. If a book is too challenging, goes one strand of wisdom, it is not for everyone. Indeed, it may not even be for anyone, given that the accusations that usually follow any suggestion of difficulty are that the work is ‘self indulgent’, or even hostile to readers. Vollmann’s expansiveness, his commitment to a level of detail that approaches delirium, his determination to stroll where others would prefer to inject pace, place him firmly in the ‘difficult’ category, but to me these characteristics are the very opposite of self-indulgence. They are democratic to the point of egolessness. Vollmann’s embrace seems limitless. It takes in pollos and coyotes, border guards, farmers, maquiladora workers, the voices of the dead, the experiences of the nameless. In doing so he gives us a difficult book, but one that is absolutely, necessarily, for everyone.

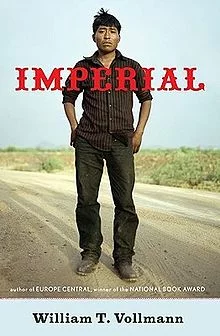

Image © Tony Webster