In 1999, when Ai published Vice, I was eighteen, the world was about to end, and I’d just started kissing this guy. ‘Dump him,’ my best friend said. ‘He has a warrant out for his arrest.’ She was always saying reasonable things like that.

I moped around my apartment. One of my roommates did coke on the kitchen table. Not a good look. The other did calisthenics in the living room. I was born disabled so I wasn’t joining her with the tae-bo anytime soon. It would be years before I’d realize what a shitshow literature is towards the disabled: if we don’t die in their books, we’re fifth business. I couldn’t find any writers like me in the anthologies. I worried that I’d need to write some based-on-the-true-life-of-a-good-little-disabled-girl poems if I wanted any kind of audience. I had to get out of the apartment.

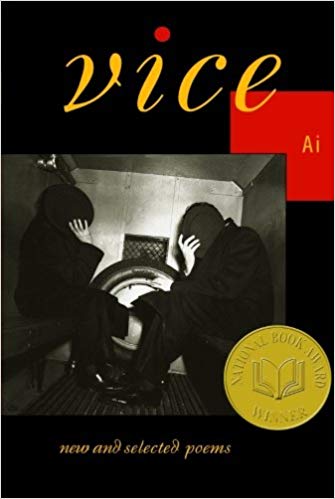

So I went to hear Ai read from Vice at The Warehouse in Tallahassee, Florida. Have you read this book? Did it change your perspective? Give you permission?

I realize that now is not exactly the time to praise the power of the dramatic monologue, the form Ai uses in Vice. Earlier this year (I am writing in 2018), Anders Carlson-Wee published the dramatic monologue ‘How To’ in The Nation. The poem ventriloquizes black vernacular, pick-pockets queer lives and riffs on the ableist word ‘cripple’. Toby Martinez de las Rivas published the poem ‘Titan / All Is Still’ in Poetry. It reads like a dramatic monologue of T.S. Eliot at a crypto-fascist Bible study group. Michael Palmer’s poem ‘Nord-Sud’ in Harper’s voices a man counting butterflies and rhapsodizing about poetry: ‘poetry, that blind ballerina.’ Frankly, what the fuck is going on?

Back to 1999: Ai’s monologues slayed me. I stood in The Warehouse electrified by this poet, this force from beyond, these voices of different characters. She could become anyone. Whoever she became, she became them entirely. As a fourteen-year-old Choctaw girl in 1866, she writes: ‘I slip the scarf around your neck, / and pull it tight, remembering: / I strangled the other baby.’ As J. Edgar Hoover: ‘I’m so scattered lately. / I feel like shattering all my Waterford Crystal. / Ask me anything you want, but don’t touch me.’ As a comatose patient raped by an aide: ‘My eyes were open.’ As James Dean: ‘I had devised a way / of living in between / the rules that other people make.’ As a stalker: ‘Outside, the early morning air chills me / and I’m glad I brought a sweater.’ As a high school senior: ‘Sometimes I still think life sucks, / but it’s better than the alternative, / which never ends.’

Perhaps because her life’s work was devoted to monologues, reviewers often mentioned her birth name and mapped her genealogy onto her poems. ‘It’s not as if I don’t know my own goddamn name, my own life,’ Ai said in an interview. ‘Since it’s poetry, people think the poems are all about me. For me, it’s stepping into other characters, creating someone from the ground up, so to speak. I try to create an entire psychology.’

I love Ai’s work because it gives me permission and reminds me that poetry invented fiction. I needed that in 1999 and I need it today. Often it can seem like the minority writer is charged with delivering the official version of the minority experience. But no. There is no such obligation. The monologue does not belong to men. It does not belong to those with privilege. Anyone can use it.

Image © commons