During the 1930s, Randall Swingler (1909-67) was a well-known public figure in Britain. A committed Communist, endowed with both charm and formidable energy, he published poetry and critical articles, edited literary/political magazines and organized cultural events. In 1939, for example, he put on a ‘Festival of Music and the People’ that filled the Albert Hall. This featured music by a variety of composers such as Vaughan Williams, and the star singer was Paul Robeson; Swingler himself wrote the text for the historical pageant that constituted one of the three concerts.

After the Second World War, however, Swingler disappeared from the public eye. The Years of Anger (1946) received far less attention than his previous books – even though it contains Swingler’s finest work, and at least two or three poems that deserve a place in every anthology of English poetry. The most important of the book’s four parts is the last, ‘Battle 1943-45,’ composed when Swingler was fighting, as an ordinary soldier, in the Italian campaign.

At his best, Swingler writes with a breath-taking simplicity and boldness. The first words of ‘The Beginning of War’ are:

At the door of the world the thought of happiness

Looks back and leaves without another word:

A woman aged, who has made her last appeal

And failed.

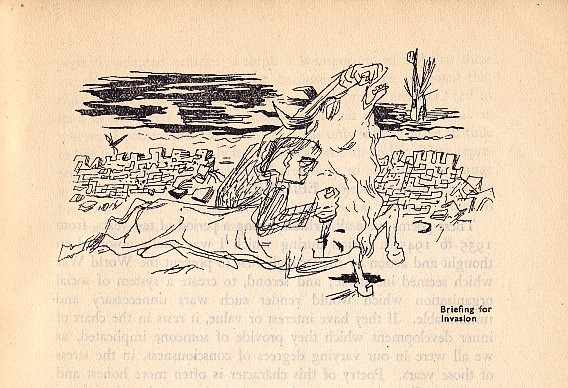

‘Briefing for Invasion’ begins with evocative sensory details that at once establish its authenticity:

Tomorrow, he said, is fixed for death’s birthday party [ . . . ]

At 0-four hundred hours when the night grows sickly

And the sand slips under your boots like a child’s nightmare,

Clumsy and humped and shrunken inside your clothes

You will shamble up the shore to give him your greeting.

The invasion in question is the 56th Division’s fiercely contested landing at Salerno Bay in September 1943. The poem’s emotional and philosophical depth, however, allows it to ripple out far beyond the immediate context. Whatever Swingler may have had in mind at the time, anyone reading the penultimate stanza today is likely to think of the Shoah:

Even though some should slip through the net of flame

And life emerge loaded with secret knowledge,

Won’t they be dumb, sealed off by the awful vision?

Or should they speak, would anyone ever believe?

Here and elsewhere in this cycle, Swingler writes with both sharp immediacy and a sense of historical perspective. The central stanza of ‘The Day the War Ended’ (May 1945) goes:

There is a moment when contradictions cross,

A split of a moment when history twirls on one toe

Like a ballerina, and all men are really equal

And happiness could be impartial for once.

Work of this order is a reproach to anyone who thinks that no great English-language poetry came out of the Second World War, as well as to those who still believe that poetry must be ‘difficult’ if it is to treat of complex and difficult experience in an original manner.

*

The first three parts of the book contain love poems – addressed to Swingler’s wife, Geraldine, who was a well-known concert pianist – and political poems. The love poems focus somewhat relentlessly on Swingler’s struggle, as a political activist, to reconcile his personal and his political commitments; some now seem repetitive and self-indulgent. The more directly political poems, however, are lucid and memorable – a far cry far from mere ephemeral propaganda. The clarity of understanding embodied in ‘After May Day,’ for example remain relevant, even inspirational, to anyone working for any kind of social or political cause:

It’s easy to lead in the open when the issue’s clear:

These things are the rewards, that rarely appear.

What’s not so easy is to lead in the dark,

From moment to moment knowing just where the spark

And just how strong, may be struck. For the real work

Is the work that no one sees, and earns no remark.

The life of the mole, patient, alert, precise,

Planting the true word in the secret place,

Never conspicuous except in mistakes. (from ‘After May Day’)

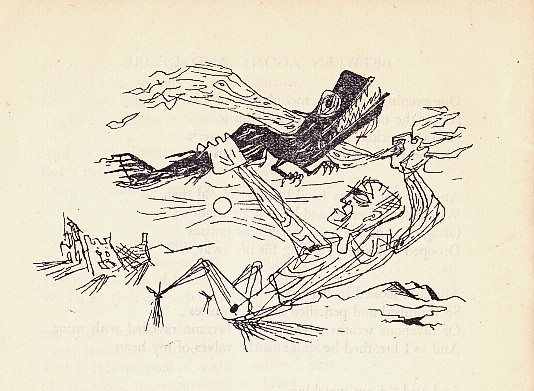

Earlier this year, the poet, editor and publisher Andy Croft published a revised and expanded edition of his exemplary biography of Swingler, also titled The Years of Anger. I was shocked to learn from this just how much has been edited out of the generally accepted view of our recent cultural history. British Communism in the 1930s and the war years was evidently more artistically fertile than I had known. Just as Swingler has been unjustly eclipsed by such poets as Auden and Spender, so James Boswell – an outstanding graphic artist and Communist political cartoonist – has been eclipsed by more modernist figures such as Moore and Hepworth. Boswell and Swingler were close friends. Yet another remarkable aspect of The Years of Anger is that it includes six of Boswell’s fierce, spiky illustrations, one of which is also used for the book’s front cover; I know few poetry collections where text and illustrations are so perfectly integrated.

Boswell’s satirical work has much in common with the better-known German artists, George Grosz and Otto Dix, and it was an important influence on Ronald Searle. Like Swingler, Boswell produced his finest work during the war. His party membership prevented him from being accredited as an official war artist and so he was able to work with absolute freedom. The critic Richard Cork has written, ‘I know of no parallel in English art for Boswell’s ability to expose and denigrate the senseless waste of a conflict which official war artists approached with such muted emotions.’

There is little doubt that it was Swingler’s communism that led to his exclusion from the mainstream of post-war British cultural life. It may also be relevant that Swingler’s war poetry was too distinctive, that it did not fit with unquestioned assumptions as to how a modern poet should write about war. Andy Croft writes, ‘The example of the anti-war poetry of the First World War had made it extremely difficult to write about the necessary, anti-Fascist War which Swingler believed he was fighting [ . . . ] The popular press expected flag-waving verse, the metropolitan intelligentsia a hand-wringing literature about living in tragic times. Swingler’s writings about war [ . . . ] were neither, expressing instead the complex, battered sensibility of the ordinary soldier and finding there something approaching greatness.’

Croft has been championing Swingler’s work for well over twenty years. That his heroic efforts have attracted so little attention points to an alarming complacency and inertia on the part of the British cultural establishment. Most of Years of Anger is included in Andy Croft’s edition of Swingler’s Selected Poems, but this, unfortunately, is out of print. A few poems are quoted in full in Croft’s biography, but Swingler urgently demands republication. It is to be hoped that some enterprising publisher will bring out both a facsimile edition of Swingler’s Years of Anger, with the original illustrations, and an expanded Selected Poems, perhaps also including a selection of Swingler’s crisp, insightful literary criticism.