In 2015 I spent more time talking about my debut novel God Loves Haiti on a global publicity tour than I did reading or writing. One of the rare books I did find time to read, French novelist Mathias Énard’s Boussole, which stars an insomniac musicologist in Vienna and his worldly ruminations on The Love That Got Away, was spectacular. Its generous language made me want to start writing a new novel, the highest compliment I could give any book.

But Boussole is not my book of the year. It did not make me uncomfortable. It did not make me reflect on my own father, who died seven days before Christmas, in 2004.

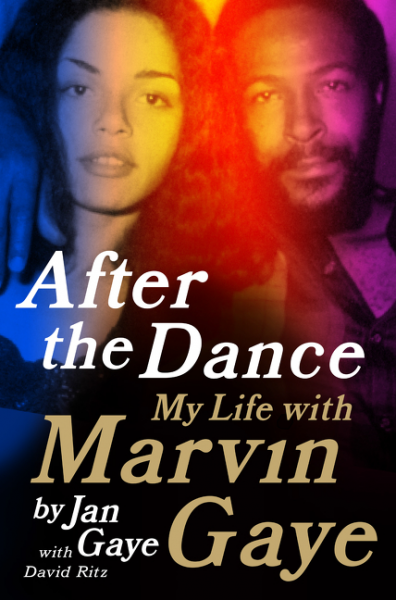

That distinction belongs to Jan Gaye’s memoir, After The Dance: My Life With Marvin Gaye. Written with the master biographer David Ritz, the memoir thrilled and upset me. Marvin Gaye was the musical giant of the 70s, beginning the decade with the timeless cool of What’s Goin’ On? and ending it with the bitter-gorgeous Here, My Dear. But the most original aspect of Marvin Gaye’s life wasn’t the agony and ecstasy of his generous soul music, but his relationship with his father. And it wasn’t just that his relationship with his father was screwed up – it’s the fact that his father ultimately killed him. Ended his life. At the end of an argument, his father pulled out a shotgun and shot Marvin dead. The echo of the blast left my ears ringing when I finished reading the book last summer. I’ve had trouble listening to Marvin Gaye’s music since. Dude was only forty-four years old when his dad killed him.

There was a stunning finality to Jan Gaye’s memoir, though not her life. She was seventeen when they fell in love, half his age, old enough to be his daughter. But Marvin died abruptly, youthfully, for are we not eternal children compared to our parents? The darkness, the silence from such a silencing, left Jan’s world – and the reader’s – bruised, forever. For most of the book, she paints the picture of an artist in full whose fullness lasted far longer than most. Yes, Marvin Gaye was a functional addict – addicted to visions of heaven, to cocaine, to the Motown corporate teat, to nubile women, to nubility itself. In the most funny-sad scene in a book filled with them, Marvin invites an LA street hooker onto his tour bus for a threesome, but then loses interest when she fails to recognize him for the celebrity he was, the most famous singer alive, a singer-songwriter worshipped by peers like Stevie Wonder and Bob Marley and a young comer named Michael Jackson.

The reader, like the lover of Marvin Gaye’s music, doesn’t get the sense that his father tracked him like cancer his entire life, but Marvin Gay Sr did. Marvin’s father didn’t like him from the day he was born. Marvin’s mother doted on him to make up for it. Marvin sought the world’s doting too and got it. Jan was the classic second wife of a successful artist – she was, and also was meant to be, a beautiful fan first and foremost. A fan and a muse. He literally sang the album and song Let’s Get It On for and to her. Her giddiness during the experience makes every page in her memoir a rush. The inner sanctum of artistic creation and celebrity has rarely been so nakedly and lovingly revealed, warts and all.

I often think the quality of our parents may be the most luck-driven factor in our lives. My own father was a retired professional football player who made up for his lack of wealth by offering us children exceptionally unconditional love, understanding, and a sixth sense for threats to our welfare. Gaye Sr was the opposite. He took pleasure in hurting Marvin as a child and didn’t change after Marvin became an adult. Subsequently, Marvin made music for the women he loved. We all loved him for it. His father didn’t. He never danced with Marvin even when Marvin’s music and money went from watershed to trickle in the 80s.

Marvin Gaye deserved better.

No one should live without a father’s love.