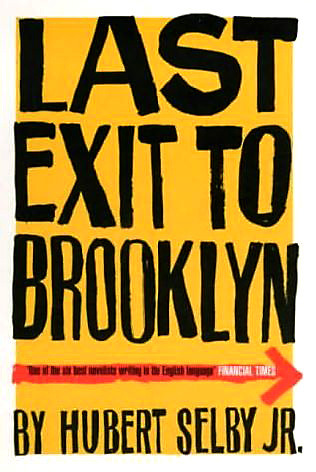

How do we define the best work of a writer as fearless as Hubert Selby Jr, a writer capable of documenting human cruelty and pettiness and stupidity with a savage compassion that can – should – leave a reader wounded and breathless? For sheer soul-hopping scale, let’s go with Last Exit to Brooklyn, a reeling, whirling account of lives lived in the most populous borough of the United States’ most populous city, a place of which we could confidently say ‘all human life is here’.

There are six parts to Last Exit: Another Day, Another Dollar; The Queen Is Dead; And Baby Makes Three; Tralala; Strike; and the coda Landsend. Each is in turns violent and tender. Each bobs from the banal to the brutal. Sometimes the brutality is banal; sometimes, with a kind of creeping, crushing sensation, the opposite. Each highlights lives lived on the edge: the edge of a city, or a country, or a manufactured idea of civility, or of some private code, some fine and diminishing line. Selby’s characters are almost always lost souls.

Rarely are they loveable. Frequently they are startlingly unpleasant. Harry, the protagonist of Strike, is abusive, cretinous, deluded and conceited, but though we may detest him we understand him; his frailties are so disquietingly recognisable; he is human, and we pity him.

In Last Exit Selby gives us such complex portraits of sex workers, street thugs, housewives, transwomen, dandies, widows, drug addicts, con artists, patriarchs. Even in their best circumstances they are inclined towards wretchedness. Selby’s power is in his ability to stay with the grotesque aspects of these wretched lives, but not once suggest that they are not capable of love, or worthy of it. His language, like his stories, can be rushed, clipped, challenging, or soothingly rhythmical. It feels not experimental for the sake of literary experiment, but as a by-product of the author’s urgency, his commitment to recreating the pulse of Brooklyn’s streets.

And so Last Exit functions as a portrait of a particular city character and also of all cities, all communities. There are specifics, but also sweeping truths. People, Selby pitilessly tells us, have such capacity for destruction. What terrible fraternity in such an unpleasant truth told with such unwavering empathy.

Frequently I come back to the idea of Last Exit… being the Great American Novel, almost always out of surprise that our stateside cousins still seem to be searching for it. Over fifty years on, it seems a more vital work than ever. In days of such human cruelty and pettiness and stupidity, we need reminding that we are all capable of savage compassion as well as the contagion of hatred.

Photograph © Luisa Rusche