All things come to him who waits

but that is merely stating

One feature of the case – you’ve got

To hustle while you’re waiting.

– Inscription on the title page of The Autobiography of Dr William Henry Johnson

‘The flag – the stars and stripes, the red, white and blue – which should have been true, was false, false to us.’ So says William H. Johnson in his speech on the 4th of July. It’s 1859, a crucial year in his life and in the US. The country is on the cusp of civil war. He’s African American, born a freeman, and in his speech he draws out the gap between the promises of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. His text is full of intentional irony, even bitter humor, as he speaks in the city of brotherly love, Philadelphia, where both those documents were drawn up. Soon he meets the abolitionist John Brown and offers to join his rebellion in Harper’s Ferry. Brown turns him down – Johnson is about to have a child, and early that December he stands watch over Brown’s body. Two weeks later he’s in street skirmishes to keep an escaped slave from being manumitted. The US marshal in Philadelphia musters a force of 2000 men to transport the slave, and Johnson describes the fight, ‘short, sharp and bitter… Heads were broken, limbs dislocated,’ and nine arrested, including him. He escapes jail that night and hides for three weeks before taking the train to New York City. He holds his own on an all-white railway car. Someone hands him a six-shooter so he doesn’t have to give up the seat. His account quells the moment’s drama but I picture it as some elaborate Wild West moment as he stands up to the conductor’s men who’ve come to put him into what he calls ‘the ‘Jim Crow’ car,’ but he would not be moved. Born a free man, he will ride where he wants.

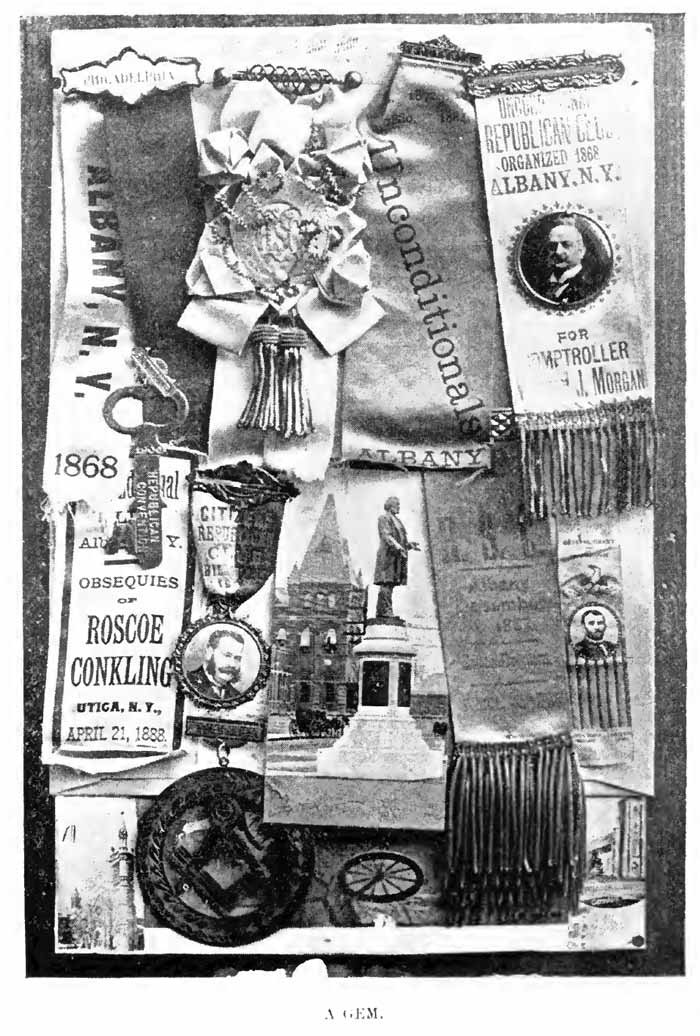

Rosettes from William H Johnson’s Autobiography

All this I learn in The Autobiography of Dr. William Henry Johnson, long out of print and never an easy read, particularly now that it’s only available as a pdf. It’s my book of the year, at least this year as the US jerks to the right, racism is ascendant and civil rights under threat. The book itself is a scrapbook of letters, speeches, dispatches to various magazines and newspapers (The Calcium Light, The Pine and Palm, Frederick Douglass’ The North Star and his own irregularly published Albany Capitol). The book is not even in chronological order, forget any kind of narrative order. There are reports from the front lines of the Civil War where he fought and celebrations of his lobbying efforts. New York State passed key legislation to desegregate schools, its national guard, even theaters, inns and opera houses thanks to his work. He helped outlaw predatory practices by insurers and attended nearly every Republican national convention even before African Americans had the right to vote. He found common cause with the oppressed – women and Irish immigrants. It’s that attitude, though, that he shouldn’t be different, shouldn’t have to pay more or be prevented from riding in whatever car he wants that is the most powerful part of the book. He writes about the average lives African Americans lead at the time in Albany, New York. They’re middle class: shop owners, homeowners, family men and women . . . Johnson knows that it’s important to be average, to be a citizen. This was the goal.

Johnson is now a ghost of history; he doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page, but I can’t let him disappear. He was from my hometown, his mother a slave on a plantation near where I grew up; his only education Sunday school – at the same church George Washington had attended not long before, and he settles in upstate New York, not far from where I live. And, he takes part in normal life, writes about these lives, the point being that this normal, comfortable life is a right. His book isn’t great reading but shows me what is possible, what heroism in the face of racism looks like, all while striving to achieve the American dream. As the book’s compiler writes in its ‘Finale,’ ‘A few more ‘Johnsons’ and our young men and women would be made to feel that life was given them for a higher purpose.’ True, indeed, meanwhile I get some idea of how to live these next four years.