One afternoon I was over at my friend Rudd’s. We were in his studio, a rough space framed out above the garage. Rudd is a contractor and photographer, and we were looking at his landscape photos. We’d been talking about a picture of a barren tree in a field burning with red brush. I said something about haunted landscapes, revenants, and he grabbed a crate off a bookcase.

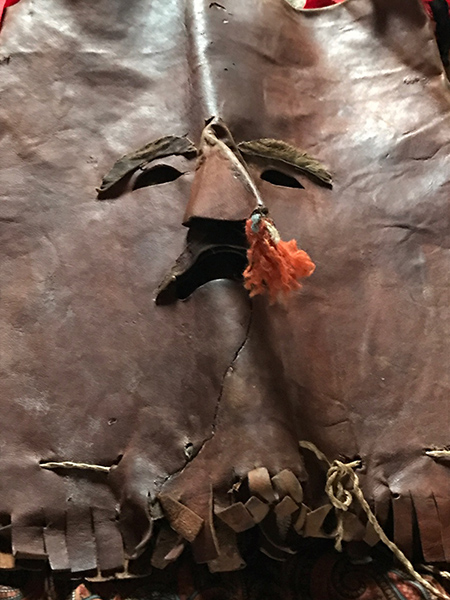

‘Now this here’ll haunt you. This is a real ghost from the past.’ His words were chewed down, the syllables nubs, and he laid the case before me. Inside, lovingly folded and nestled together, were a leather mask, a dress and pantaloons – both made of a red paisley calico. A metal horn snuggled between them. They were part of a disguise from the 1840s, a costume that had been declared illegal. He spread it out on a table before me. Red ribbons and braids dangled in front of the leather hood.

Rudd picked it up as if it was nothing. Laid out, the dress looked more like a loose smock or housecoat than what I pictured women wearing in the early Victorian age. But the outfit wasn’t worn by women. The leggings, he explained, gesturing at the paisley trousers, had been designed to cover your boots, so no one could recognize any part of you.

He held out the mask. It was nut brown leather with rough slits for the mouth and eyes. ‘Try it on. Come on, see what it’s like.’

‘But, it’s so old, my skin . . . the oils on my hands. It should be in a museum.’

‘No way, not unless it’s on permanent display. This is part of my family, my heritage, and it’s not getting stuck in storage somewhere in Albany or wherever.’ He pulled the hood on.

With its crude holes, he looked like he had come out of a horror film. I could just make out his lips and teeth, but his eyes were sunk in darkness. Eyebrows were roughly sewn on in leather. Stitch marks crossed the face. The nose pointed like a beak, as if he was dressed as a hybrid bird-man-monster. Reading glasses dangled around his neck, and they made his whole appearance more disturbing. The glasses, this quotidian symbol of middle age, held him in one world, and the mask made him part of another. Rope was threaded through the bottom of the hood to tighten it at the throat. That way, he said, no one could yank it off and expose you.

The costume was worn as part of an uprising in 1844 and ‘45 in upstate New York, where I live. Poor farmers rose up against entrenched elites and tried to take over the land. Called the Anti-Rent War, it was one of the earliest moments of rural populism in the US, and something few know about outside the Catskill Mountains. People like Rudd’s relatives had donned these costumes and formed ad-hoc militias they called ‘Calico Indians.’

In the guise of ‘Indians,’ they were invoking the Boston Tea Party, and probably also romantic images of Native Americans – some combination of awe, dignity and terror. James Fennimore Cooper’s novels, which are set nearby, had popularized the idea of the noble savage. There had been wars over this land already – the Lenni-Lenape tribe who’d lived near where my village now stands had fought off white colonizers little more than sixty years earlier in the 1770s, chasing them from the territory, but by the time of the masks they had been forced from the region themselves. I don’t know why exactly my neighbors styled themselves as Indians, and there are no historical records about how the Native Americans felt about this appropriation, but the identity gave the white men license to pick up arms and break the law. They added ‘Calico’ to the name for the cheap fabric they used for their dresses.

The mask from the Rudd family’s Calico Indian costume

My village Margaretville sits in the Western Catskills, a place of rubbed down hills, the continent’s oldest. The furthest north part of Appalachia, my county is also one of the poorest in New York. I left London to live here more than a decade ago, and in a remote valley I was now building a house.

Down the road from the house site, a waterfall crashed over broad boulders. Posted signs tried to intimidate anyone from trespassing. I’d clamber down anyway, and just below the falls were green mossy rocks laid up like an old stone wall. Sometimes I’d find beer cans there, once the carcass of a deer. On my land, set in a grove of wizened apple trees, was a ruin of an old farmhouse and barn. The stone foundations were all that was left, and when I call it a ‘farmhouse’, that’s a lie. It was never anything that grand. It would have been a shack, six feet wide and six feet long, and now it was full of trash, the kind of junk that would thrill me as a kid: barrel hoops and broken bottles and metal milk cans. I couldn’t picture the kind of life lived here, the place was so small and wet.

My husband and I bought the land from a woman named Muriel Scott Robinson, who’d grown up here. She’d died recently and that year I asked her husband about the ruins. He emailed:

Muriel’s grandfather bought the farm with that small farm, called ‘the old place’, as part of the total purchase. It was in ruins when I first met her so I don’t think anyone lived there in the twentieth century. It must have been leftover from the anti-rent war. It was too small to support more than a few cows, pigs and other animals associated with primitive farming, yet there had to be enough to make rent for the patroons. Must have been a hard life.

That was all I discovered for years, until the head of the local historical society sent me a map from 1869. It looked vaguely familiar; the roads hewed to ones I knew, even if the names were different. There were places on it, though, that I’d never heard of: Sunny Dale, Reserve Home, Union Home, Quiet Reserve, Silver Dale and Solitude. I traced my finger along my village Margaretville and up onto my road Bull Run. It eventually turned into a dotted line to indicate the road was no longer a road, but a rough path. Just before it changed, there was a name where my land should have been, ‘A. Kettle.’ It floated just above something called ‘Sunny Side’ and had a number beneath, 127. This, I realized, was a parcel number.

*

In a town called Delhi (pronounced ‘Del-high’), my local county seat, I went to the courthouse to research property deeds. Late Victorian with a cupola and a mansard roof, the building was imposing and sat on a green with a bandstand. In the clerk’s office, lights buzzed overhead. The room was lined with bookcases full of deeds. I read through lists of grantors and grantees, years and dates. The deeds were written in fountain pen with fancy flourishes that were nearly impossible to decipher, and the words seemed to be in a foreign language. There was ‘appurtenance’ and ‘indenture,’ ‘situate’ instead of ‘situated.’ Each deed referenced ‘Heirs and assigns,’ and ‘assign’ was not a verb but a noun, a person. This was the language of capitalism, of ownership.

Studying the deed of Muriel’s land, I saw something strange in the document. It excluded two acres around the stream. The wording explicitly stated that the waterfall wasn’t hers, but it was unclear why or even who owned it now. At the same time, the document laid out all the land’s previous owners. First had been Morgan Lewis. Powerful and rich, he’d been governor of New York in 1804 and fought against Britain in the Revolution and the War of 1812. His father signed the Declaration of Independence, and Morgan Lewis had co-founded NYU where I taught. Next, in 1847, Orson M. Allaben and his wife Thankful sold the 152 acres to someone named Augustus Kittle and his brother. Allaben was a doctor and the town’s first postmaster, and he too sold everything but the couple acres with the brook falls. There was a bigger riddle as well – Kittle had three deeds. He bought the same property three times over. First with his brother, then again in 1865 just twelve days after Lincoln was assassinated, and finally in the 1870s.

I had no idea why I kept looking into all of this. It was just that his land was part of my land and there was a mystery about the three deeds. I learned that Kittle’s first-born son was named Lincoln. This in 1864 when the Civil War was unpopular in the North. Six months earlier riots had spread across Manhattan and Brooklyn as the draft was imposed in New York, and black orphanages were burned, killing the children inside. Yet on our land a Lincoln was raised, and in the current moment of resurgent racism I wanted proximity and history to connect me to this man and his child. I wanted his ideals to be part of the land I was building on. But, I discovered too that Augustus Kittle had been tried and convicted of manslaughter – in 1845.

*

All these deeds tied the land to an era of vast wealth that began in the early 1700s when the US was not united but ruled by a queen then a king. Territory in the English empire was summarily taken from its indigenous inhabitants. In upstate New York, it was given to wealthy men, in the belief that ownership of vast parcels – thousands and thousands of acres – represented stability. Sometimes there were treaties; occasionally the land was ‘bought’, or rather white men believed they were buying the land. The Native Americans thought they were sharing it – this is what happened in Manhattan when the Dutch ‘bought’ the land for twenty-four dollar’s worth of trinkets.

Now my deed, Muriel’s deed and Augustus Kittle’s all contained a phrase: the Hardenbergh Patent. It was a land deal signed in 1706 and again in 1708 with two different signatures, neither of which belonged to the man for whom the patent was named, Johannes Hardenbergh. He was just the front for seven other investors with conflicts of interest that, if they had been revealed in court, would have broken the law. But these were not the type of men who were taken to court. The group included the attorney general and the surveyor general. No one today is sure of exactly how much territory there had been in the patent – maybe two million acres, maybe one and half – but it stretched from the Hudson to the western Catskills and beyond. Across the patent, the English and Dutch landowners, patroons they were called, all believed that great wealth awaited them in the Catskills: mines, gold and ore, and tenant farmers to pay rent.

The idea of owning your own farm is ingrained in the US, but people on the Lewis Tract and across the Hardenbergh Patent didn’t own anything. The land was controlled by the rich. Here was a version of America that didn’t fit the national narrative of overthrowing aristocracy. Everyone who lived near me paid rent. Fifteen thousand of the 20,000 acres in the Lewis Tract were leased to tenants. Life was so tough roads were often named ‘Hardscrabble’ as if to memorialize the struggle, and the soil was so poor there’s a saying for it now: two rocks for every dirt. Poor tenant farmers would live and die in hovels like the one near our house. Almost none of the leases were recorded at the county clerk’s office, but finally I found one. It belonged to Augustus Kittle’s uncle, Frederick. In 1837 Frederick and his wife Adah purchased a lease, and the couple then had to pay Morgan Lewis rent yearly on the first of February in bushels of ‘good clean sweet merchantable winter wheat.’ (There were no commas in the deeds).

The rent continually went up. After the first decade, starting in 1846 ‘and every year thereafter’ Frederick Kittle was supposed to deliver ‘four hundred and eighty pounds weight equal to eight bushels’ to the Hudson River, nearly two days’ ride away. This was on 34 acres of land so poor that growing any wheat was nearly impossible. Meanwhile, the lease excluded anything that might make the tenants money. Any ore or mines were kept back for Lewis, and so too were any mill sites and the two acres around them.

I realized that the waterfall so conspicuously missing from Muriel’s deed must have been owned by Lewis. The rocks along its sides had been a mill race; they had been money. For the landlords, with their thousands of acres and multiple homes, the income had to be negligible. No matter, they kept it for themselves. It allowed them to earn off their tenants’ grain even before those tenants paid rent.

Frederick Kittle’s lease also spelled out just what would happen if he or ‘his heirs and assigns’ were ever behind in the rent: ‘It shall and may be lawful to [ . . . ] reenter and distrain and the distress [spelled distrefs] and distrefses which shall be there and found and taken, to lead drive chose take or carry away impound and dispose of until the said rents and all arrears thereof (if any shall be) unto the party aforesaid of the first part his heirs and assigns be fully paid and satisfied.’

To translate, the landlord or any future owners could come in and take what they wanted to make up the debt anytime they saw fit. They didn’t even need to go to court. That was what ‘distrain and distress’ meant.

In the summer of 1844 the tenants went on strike. They stopped paying rent. Signs appeared in windows, ‘The land is mine saith the Lord.’ Farmers formed anti-rent associations, and members paid a ‘tax,’ they called it, two cents an acre to fund lawsuits challenging landlords’ titles and provide relief for a farmer if the landlord seized the property. Men donned masks like the one in Rudd’s box as they revolted against the landlords, the Lewises and Livingstons and the like.

*

Back in his studio, Rudd showed me the horn. It looked like a kid’s toy, and he explained that it had been used originally to call men in from the fields for dinner, but in the rent war it was blown to rouse the Calico Indians for battle. They forbade any other use for the instrument. They were the enforcers. If the bailiffs or sheriff came with papers for a sale, the Calico Indians captured the messenger. They burned the documents and tarred and feathered the person delivering them.

Tarring and feathering was no peaceful protest. It was torture. A crowd stripped you naked and poured boiling tar on your flesh. Then you were either rolled in feathers or had them dumped on you. It was the vigilante justice of the lynch mob, and the Calico Indians used it to send back their own message to the landlords. If the auction wasn’t cancelled, the Calico Indians intimidated any potential bidder – or worse. They’d shoot and kill the livestock, so the farmer’s ‘property,’ the animals, had no value.

These were marauding bands of young men. The Calico Indians had little to live for. They were poor and dispossessed, they had no farms, no future, just futility, and the air around them was heavy with frustration. It felt familiar. The Calico Indians had no part of the dream that was America. Augustus Kittle was sixteen that year. He was one of the young, the dispossessed, stuck at home. ‘Laborer’ was the term for them; that’s how he was described in the 1845 state census as he lived on his father’s farm. This was who I share my home with.

*

In one light the early 1840s looked like our present moment: the only jobs were no-skill, low-wage labor. Money accrued to ever-wealthier people, and everyone else was left behind. The Panic of 1837 set off a deep recession fuelled by speculative lending, a land boom and bust, bank reserves perilously low and then tightening credit, all against a backdrop of massive demographic change. The internet has often been called democratizing, but then people were literally newly enfranchised. In the 1830s in the US all men (all white men, that is) were given the right to vote, and with this burgeoning freedom, cheap newspapers exploded. Every partisan point of view had a press behind it, and there was little ethos of impartiality. It was like social media: everyone had a voice, regardless of the truth of what was said. Across the country (or what there was of the country at that point) rural America was in crisis. Farms failed. There wasn’t enough land for everyone, and what land there was had been depleted. People flooded into cities. Wages were cut, and the jobs available were poor. There were no unions, no minimum wage or maximum working day or any labor protections. Conditions were perilous. Anti-immigrant riots spread across the cities. It was an era of rage: recession, riots, rural America in revolt.

I read about that war, the Anti-Rent War, in Jay Gould’s 1856 History of Delaware County. Gould was from Roxbury, just north of me, and he wrote of the summer of 1844 and how terrifying the Calico Indians had been. His dad owned a tavern and was ‘Up Rent’, as those were called who were on the landlord’s side. They also styled themselves ‘the Law and Order Party’, a phrase that sounds remarkably current. Gould described his panic at nine years old, when his father stood up to the bands of calico-clad men.

With demonlike yells [they] rushed up and surrounded Mr Gould, who was standing with his little son in the open air in front of the house.

We were that son: and how bright a picture is still retained upon the memory, of the frightful appearance they presented as they surrounded that parent with fifteen guns poised within a few feet of his head, while the chief stood over him with fierce gesticulations, and sword drawn. O, the agony of my youthful mind, as I expected every moment to behold him prostrated a lifeless corpse upon the ground. His doting care and parental love had endeared him to his family. But he stood his ground firmly; he never yielded an inch.

His father lived, and Jay Gould, the son, became a railway magnate and a robber baron so hated that he was assaulted on the streets in New York City by strangers. As he wrote, he dismissed the Calico Indian’s ‘treasonable designs,’ and described how the rebels had aligned themselves with, ‘Followers of Fourier and Owen, world conventionists, who gave ready support to every scheme, however wide the mark.’

That Fourier was Charles Fourier, the French socialist philosopher who espoused communal property and liberation – personal, political and sexual. He’d also coined the word ‘feminism’. And the Owen was Robert Owen, the Welsh industrialist turned socialist who had witnessed the wreckage of capitalism in British factories, and moved to the US to create the first intentional community dedicated to socialism. This gave me hope in my rural rebellion. My neighbors, the Calico Indians, were aligned with socialists and progressives.

Anti-rent newspapers were founded in Albany and Delhi. The one in Albany, The Freeholder, was edited by an Irish chartist Thomas Devyr who’d had to flee the UK for his radical views. The Delhi paper was called The Voice Of The People. Its subhead reads: ‘Not for me but my Countrymen.’ An anonymous poet from my township penned frequent odes to the Albany paper like ‘The Farming Men:’

Down rent your glorious watchword be,

Freedom is in the sound;

Proclaim with trumpet loud and free

The welcome tidings round.

Long have you stood with hat in hand

And borne your landlord’s frown;

And seen your property distrain’d –

Your freedom trampled down.

Now in the cause of justice rise;

United firmly stand.1

The more I read, the more I discovered the names of neighbors and people whose relatives I knew. If you walked up my land and continued to the ridge you would see the Searle’s farm on the other side. Lumen Searle wrote to Devyr, the chartist, at the Albany Freeholder praising a pamphlet Devyr penned that proclaimed equality would come from destroying the aristocracy. I also found Orson M. Allaben, who would sell Augustus Kittle the farm. Allaben and his brother Jonathan were both local doctors who gave anti-rent speeches to huge crowds.

The anti-renters aligned with a group of radicals in Bushwick and Williamsburg called the National Reform Association.2 The organisation’s platform called for redistributing wealth by redistributing land. All settlers would get a smallholding. ‘Vote yourself a farm!’ emblazoned their banners. The Reformers stood for equal rights for women and abolishing slavery. They demanded a 10-hour workday and cooperatives where workers would band together to sell what they produced, each with a share in the proceeds, cutting out the middlemen, the capitalists, profiting off the poor.

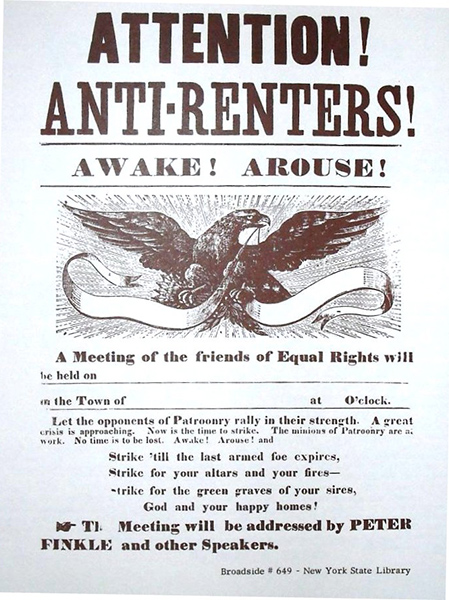

A poster advertising an anti-rent meeting

In May 1845 the National Reformers had their first convention. Robert Owen, the campaigning British socialist, addressed the assembly. ‘No man made the land,’ he said, ‘no man could give title to it.’ Jonathan Allaben was there too, right in the middle of it all. He gave a speech, and from town to town upstate he addressed Anti-Rent associations and advocated destroying the landlords. ‘Allaben has been forward in the indian system,’ one man testified later. Another: ‘I heard Allaben speak talking in favor of the indians the landlords ought to be tarred & feathered the titles were not good.’ Others said that he did not support bloodshed but ‘went on a tirade about feudalism.’

From the start of 1845 the stakes rose. In January, New York’s governor outlawed disguises, and also made it illegal for groups of three or more to gather together in costume.3 Anyone who refused to help bring someone to justice, ‘is subject to a fine of two hundred and fifty dollars, or to imprisonment not exceeding one year, or to both.’

The new law just emboldened the Calico Indians. People talked of wars fought and wars to come. ‘Don’t you see the ball a-rolling,’ Allaben said in one speech. It was a revolution – or a way of finishing the revolution of 1776. George Evans, brother of a pacifist Shaker Elder, called for change by ‘political action, or, in failure of that, by revolution.’ Allaben demanded a revolution at the ballot box, but said, ‘If the sheriff runs his head in a tar bucket, it’s not their (the Indians) fault.’ Devyr declared, ‘The gentlest means possible ought to be used. But, that failing, use the gentlest means that may be necessary.’

The means were not particularly gentle in Delaware County. Pitched battles, neighbor against neighbor, were fought in the towns all around me. Calico Indians intimidated anyone on the landlords’ side. They’d attack acquaintances who delivered rent demands. In retaliation deputies rounded up suspected rebels and harassed their families. The Calico Indians attempted to break prisoners out of jail and kidnap officials. This was not peaceful resistance, and years later one participant said, ‘If the anti rent war had happened after the Civil War it would have been a war of blood.’

The Calico Indians’ greatest enemy was acting undersheriff Osman Steele. He was vigilant and driven and took great pleasure in goading the anti-renters. He hectored crowds and came on horseback flanked by followers to ensure sales went forward. He arrived in the middle of the night to make arrests, and was said to have tortured a man’s wife to make her give up her husband. One historian called Steele a bully; another writing in the 1880s described him as ‘bold, forward, officious’. Not long before the Rent War, he’d been arrested himself for battering a woman. As undersheriff, he took to the law just as he’d taken to breaking it. In a portrait of him in the county courthouse, he has an imperious expression: red hair and a long nose and sleepy eyes over something like a cravat. Turned to the side, he looked down at the painter, or at us.

‘Lead can’t penetrate Steele,’ he boasted in March 1845. The taunt is painted on a sign now as you drive into the town of Andes, just to the west of me. There, he was surrounded and kidnapped in the tavern. Eventually marshals freed him, and Steele believed himself impervious.

In Andes earlier that summer Jonathan Allaben addressed a crowd. ‘As many as 200 indians and 4 or 500 pale faces come out,’ I read in a statement. A farmer in the town, Moses Earle owed rent of $64, about two thousand dollars today, to Charlotte Verplanck. Verplanck was going to have a sale through her land agent (and nephew) John Allen for the ‘distress’ of this $64. Her lawyer in Delhi, Peter Wright, would oversee the proceedings.

The date was set for 29 July. Hundreds of Calico Indians showed up high on the ridge where Moses Earle farmed, and the sale was postponed until 7 August. A few days before, he met with his neighbors and they all agreed he shouldn’t pay the rent even though he now had the cash.

That night the only light was a thin sliver of the waxing moon. A group headed by Warren Scudder, a 33 year old man with black curly hair, rode over in a wagon with a handful of others. Their disguises, guns and weapons were concealed in the cart. They told people they were going fishing. No one mentioned seeing a rod or tackle. Fishing was code. They were on their way to Earle’s, nearly twenty miles away. They stopped at a tavern and bought a half-gallon of whisky. They got food and more drink somewhere else. Someone told them the easiest way was over Hubbell Hill to Beeman Hill, my hill and my road. They ‘staid the night’ with Clark Sanford – just up from me.

Someone else in Scudder’s group, Zera Preston, recounted that at the Sanfords’, ‘They got us breakfast did not pay anything.’ Preston was fourteen. I saw the boy now in my mind – skinny and angry in his baggy calico dress as he took up with grown men full of righteous rage. He said two other boys met up with them, and I wondered how old they must have been if this child himself could call them ‘boys.’ The Sanford brothers, Alonzo, Charles, William and Levi, joined them. So did Augustus Kittle.

Warren Scudder announced to the group: ‘The first man who bid on the property would be death to him. Cattle would not be shot.’ The implication being people would. The group was drunk by the time they reached Moses Earle’s. Other Calico Indians appeared at the Earle farmhouse for breakfast. High on the mountain in the meadows, the Calico Indians gathered in the long grass. Witnesses reported seeing men clutching bundles under their arms, crossing fields as if to work. The bundles would have contained dresses and masks. A hundred and thirty Calico Indians came, one man guessed; 200 another said, and a third reckoned 500. There were also ‘pale faces,’ people in civilian clothes, who had come to watch. The sheriff arrived, and announced they’d hold the auction in the road, away from the Indians. The sale would proceed uninterrupted. Warren Scudder faced off against Peter Wright, Charlotte Verplanck’s agent.

I read account after account of the events that took place over the next half hour:

Isaac L. Burhans: Scudder had on a red dress – He had a sword – It was a crooked sword, silver plaited – I understood he was Chief – Preston had a musket – Scudder was Blue Beard . . . Wright said if the indians touched him he should defend himself.

Zadoc P. Northrop: Heard threats about going home feet foremost in a waggon.

Richard Davis: Wright stood at the side of the road and in it & the indians were in line. An indian spoke to Wright. The indian put his sword against Wright’s breast. Wright said I am here to protect property – the indian spoke & said that Wright had no property – the indian said to W. if he bid off the property they would shoot him.

Daniel Northrop: Wright put up his hand & told him if he molested him he would make a hole through him Scudder then drew a pistol from his pantaloons pocket. Wright said I know you, Scudder said you can’t swear to it – Scudder had on a red face & red trimmed dress . . . It was said to Wright if he bid off the property he would go down the hill feet foremost. Some said he would get what they could not buy at the grocery and that he would chew something harder. They both behaved well.

During this exchange Osman Steele showed up, riding with his brother-in-law Constable Erastus Edgerton. They came, it seemed, for the sport of it. They didn’t need to be there. The sheriff was already on site and in charge, or as in charge as he could be. On their horses, Edgerton and Steele stood ten yards from where the Calico Indians were massed.

William Brisbane: Steele said I dare you to shoot my horse. Neither Edgerton & Steele or Wright had the pistols drawn then. Edgerton said the first man that offers to stop me . . . I will shoot him or shoot him dead.

Dr. John Calhoun: I saw Steele ride around a circle some 3 or 4 rods – present his pistol & fire among the natives. He rode directly right at them. After he fired there was an instantaneous discharge spat, spat, spat.

Adonijah Stansbury: I was amazed, I stood stock still it gave me a terrible bad I was very bad. I can’t tell how many guns were fired. There were two flashes one after the other. At the first there were 6 or 8 guns fired. The second & next time as quick as thought 3 or 4 guns went off. I kept my eye on Steele. I saw E’s horse down as quick as thought after the firing ceased. The whole firing lasted 8 or 10 seconds. After Steele drew his pistol his horse wheeled to the left & I saw his horse was wounded & then I saw Steele was wounded and he pitched forward & fell off his horse as quick as thought.

Joel M Bailey: His horse reared pretty much at the same time & Steele was shot at about the same time the horse reared & I saw Steele’s coat fly on both sides I did not see the ball that pass through Steele’s body. The shot I saw when his coat flew hit higher up than his bowells & both his coat flaps flew up.

William Sprague: I heard some one call to help carry him in & I went into the house with them & I pulled off his Shoes. Dr Cahoon told me to take off his shoes & I did so & lay him down. Steele said when on the bed, I can’t live. Wright started for Delhi with the gray horse & Steele said you must not tell my wife of it. Steele said O dear me I can’t live. I thought of his wife.

Brisbane: Someone at the bedside made use of the remark who fired first? Someone said it was Steele. Peter Wright said no Steele did not fire & Steele then gave forth an ejaculation of pain & said O dear. Yes said Steele I fired. That was all I heard in the house.

Calhoun: Steele said how could the cruel wretches shoot me? Brisbane then said how could you shoot at them? Their lives are as dear to them as yours to you.

Moses Earle: Steele said on his death bed ole man if you had paid your rent as you ought this would not have happened. I said if you had staid at home and minded your business this would not have happened.

A sign in New York indicating the location of the confrontation

After the murder, the governor declared the county ‘in a state of insurrection.’ He sent out the militia. Law and Order posses overran local farms, arresting anyone they could and sacking their victims’ homes. People started giving affidavits, attesting to what they did on 7 August, and sharing whatever they’d heard. Many were reported as being ‘pleased’ Steele was dead, and denied it before the jury. Calico Indians burned their dresses and went into hiding. Warren Scudder ran north to Canada. His father, a Baptist minister, was thrown in jail as officials tracked him. Zera Preston was arrested almost immediately. Although he at first refused to testify, three days later he talked about the two other boys, the way they’d put on the dresses and the food they’d shared at the Earle farm to feed the insurgents. He said he ‘carried kind of a musket from home.’ Allaben and Searle were dragged in front of the grand jury too. Neither attended the sale, but Allaben and his speeches were mentioned in countless statements.

The indictments that followed strung out a litany of names. One listed the Sanford brothers, Augustus Kittle, his cousins Valentine and Charles, Zadoc and Daniel Northrop, Warren Scudder and Zera Preston who:

With force & arms unlawfully wickedly willfully feloniously riotously & tumultuously did assemble & gather together to disturb the peace of the people of the state of New York & did then & there paint discolour cover & conceal their & each of their faces and did so disguise their & each of their faces persons as to prevent themselves from being identified& did then & there arm themselves with swords dirks guns rifles pistols & other offensive weapons & while so having their& each of their faces painted discoloured, covered & concealed & their & each of their persons do disguised as aforesaid & being so then & there unlawfully riotously & feloniously assembled & gathered together as aforesaid & being so armed with swords dirks guns rifles pistols & other offensive weapons did then & there make great noise riot tumult & disturbance for a long space of time to wit for the space of one hour then next ensuing to the great terror and disturbance not only of the good people then & there inhabiting, residing & being but of all other good people of the state of New York –

The long lines of adjectives and adverbs were almost comical.

I studied Steele’s portrait and a photo of Jonathan Allaben taken more than a decade later. His beard had gone gray, and his brow was pinched in worry. He wore a somber suit, his hair carefully combed and oiled in place. There was so much I wanted to ask him about violence and values and if the war had achieved its ends. I wanted to know about what he’d believed and the lengths he’d go to in achieving it. All I had for an answer were second-hand documents, a jostle of ideas and the picture of these young men in my mind. Warren Scudder and his red face under the red mask, Kittle with his mask up, holding a revolver, maybe, and Zera Preston with his ‘kind of a musket from home’.

Augustus Kittle, Gus, his family called him, seventeen and a laborer. In my mind he was lanky and headstrong, with red hair. Not hopeless; he fought. If you fight, you think change is a right. Warren Scudder drove his father’s team of horses. His father approved of the cause; he’d lent his horses and flown an anti-rent flag from his wagon on the Fourth of July. I found no testimony for Augustus Kittle. My guess was he disappeared for a while after Steele was killed.

*

The land was not redistributed. It wasn’t made free. The Calico Indians lost. But a couple years later, Augustus and his brother bought the farm. It was 1847, and they purchased it from Orson Allaben, the doctor who’d given speeches with his brother. Rudd’s family bought their farm in 1848. Come the 1850 Census I found more Calico Indians with their own property. I didn’t know how they scraped together the money. My guess was that sympathetic people like the Allabens helped, and that Kittle’s three deeds were tied to a mortgage.

In a sense they did win. Soon politicians started talking of land and injustice. They took up the anti-renters’ arguments, and in 1854 the Republican Party was formed in Ripon, Wisconsin. The town was on the site of what had been a Fourierist phalanx, and here the party courted broad coalitions, ‘special interests’ we’d call them now: abolitionists, suffragettes, Fourierists, anti-rent organizers and land reformers. They argued that every man deserved to own the land he worked, only instead of redistributing existing land in private hands, the policy was for public land, Western lands, ones that seemed easy to give away. This policy became the Homestead Act, passed in 1862 in the middle of the Civil War. Any settler who went West got 160 acres. That was my neighbors’ legacy. In the Rent War they’d fought cloaked as ‘Indians’, and their actions led to a law that would displace thousands of Native Americans. Settlers were sent out to establish single farms in hundreds of acres that added up to hundreds of thousands of acres across the country, much of it indigenous territory – all because the land is mine saith the lord.

This call still reverberates. In early 2016 in Eastern Oregon’s high desert the Bundy family and their followers took over a federal wildlife refuge believing that all government property should be in private hands, their hands. The group refused to pay for grazing rights and staged an insurrection calling themselves ‘patriots.’ Like the Calico Indians, they too claimed to be returning to the ideals of the American Revolution. Carrying long arms and pistols, they dressed as cowboys, flew the American flag and rode horses. The land was theirs, they claimed, ignoring that the land they wanted had been the Northern Paiutes’ first.4 The ranchers’ actions were full of entitlement and rage.

James Baldwin wrote, ‘The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.’ He was writing about how white America ignores its racist past. History and its violence, like this violence, is a ghost that haunts our country. Calling the moment we’re living through unprecedented lets it exist in a void, which gives it more power. I watched the blank, puzzled faces of pundits denying history. But this is America, and America has always been about violence and injustice, has always been bloody, and has always seen money accrue unfairly to the rich.

*

One afternoon I walked up the track behind Ray Sanford’s farm over Salmon Beeman’s hill. I followed the path Warren Scudder took with Zera Preston and a band of others before they’d met up with Augustus Kittle. It was autumn and the view was bucolic, hay wagons and pastures and the trees starting to turn rust-red and crimson. I crossed through the woods and came out on a paved road on the other side. It was dotted with vacation homes and views of mountains. I realized back then the farms and fields would have reached to the sky. At the time the forest had been disappearing. I studied the map from 1869, trying to envision my home in 1845.

That essay of Baldwin’s is called ‘Unnamable Objects, Unspeakable Crimes’. There’s another passage in it where he writes about how we hold our history inside us:

It is with great pain and terror that one begins to realize this. In great pain and terror, one begins to assess the history which has placed one where one is, and formed one’s point of view. In great pain and terror, because, thereafter, one enters into battle with that historical creation, oneself . . .

I was terrified at what I’d learned. I had wanted to understand the civic values of the place I live, and now I stood on the side of a mountain believing that violence was the basis of my country’s democracy. I agreed with my neighbors and their values, but they had been terrorists. Looking at their history I saw brutality tied to progressive ideals. My neighbors tarred and feathered people they knew. But they also got change. Nothing would have been transformed had they not taken up arms.

That afternoon at Rudd’s I put on the mask. The leather was stiff and curiously smelled of nothing, not dust or leather or age. I peered out the holes, scared to breathe. I didn’t want to damage the hood, but I held my breath too because I wanted change so badly. I’d secretly thought if I put on the mask, I’d see something – ghosts, the past perhaps, but that whatever happened I would be transformed. That those spirits would come alive for me. They didn’t. The original residents of my town, the Lenape, were long gone; Kittle and Preston were still angry young men. I think, though, they fought justly. What else was there to do but fight? Only who gets to decide which battles, and what causes? And at what price does violence come in a democracy?

1 One of the odes was set to Robert Burns’ ‘Battle of Bannockburn,’ appealing particularly to those who’d fled the Highland Clearances and moved to the Catskills, and what amazes me is how internationalist the Anti-Rent War was.

2 It was led by George Evans, whose brother Frederick became a Shaker elder. (Both were inspired by Owen and Fourier). Others included Greeley and Albert Brisbane, who’d imported Fourier’s ideas to America, as well as the chartist editor Devyr – and Jonathan Allaben.

3 A version of that same law against disguises is still on the statute books in New York State, and was used to prosecute Occupy protestors for wearing Guy Fawkes masks.

4 The Paiutes had lived in that region of the West for thousands of years and were corralled onto the land the Bundy family took over in the 1870s. Soon after they were kicked off it, when grazing rights were given to white European colonizers.

Cover image © Mary Early, a WPA mural from the 1940, Delhi New York post office