On 3 March 1873, the Comstock Act was passed by the United States Congress, making it illegal to send any ‘obscene, lewd, or lascivious’ books through the mail. The law was used to suppress birth control and abortions, but also led to the banning of classics such as Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, Boccaccio’s The Decameron and, later, to persecute modern authors like Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, William Faulkner and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

The man behind the law, the eponymous Anthony Comstock, considered himself a ‘weeder in God’s garden’, and was behind a number of placard-appropriate catchphrases used to rouse support for his Victorian moralising. His best are probably, ‘Morals, not Art and Literature!’ and ‘Books are feeders for brothels!’

Here are some of our favourite books banned by the Comstock Law:

- Ulysses by James Joyce. The Little Review had begun publishing episodes of Ulysses in 1918. But following the first publication, three issues of the magazine were seized and burnt by the U.S. Post Office for containing ‘obscenity’. In 1920, a copy of the magazine containing the ‘Nausicaa’ chapter landed in the hands of a New York attorney’s daughter. Her father swiftly brought the matter to the secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice – Mr Anthony Comstock. This sparked obscenity charges against the magazine editors, who were seen as encouraging radical politics, and the editors were found guilty under laws associated with the Comstock Act. Joyce’s novel was effectively banned from publication in the United States for just over a decade, until Random House won a case in 1933 that affirmed free literary expression.

- The Canterbury Tales by Chaucer. Yes, they even banned The Canterbury Tales. Why? Mostly due to its sexual anecdotes and frequent swearing. The work does, after all, contain some of the oldest known uses of arse, shit and ‘queynte’ (as spelled by Chaucer). Any editions that did make it to press had to be severely abridged in order to keep the smut out.

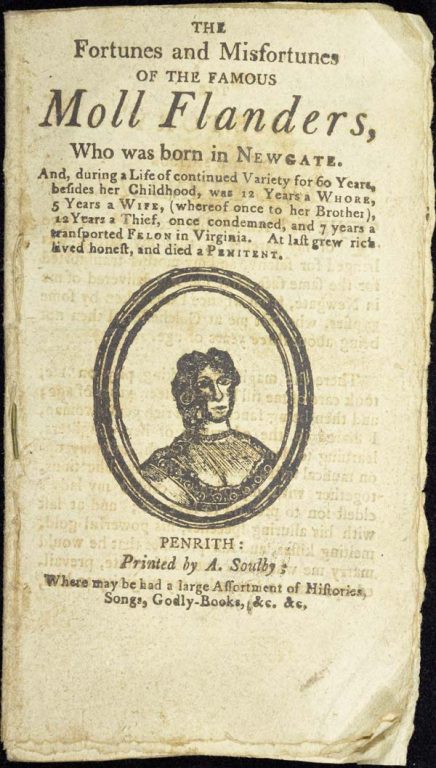

- Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe. Another victim of the Comstock Act, Defoe’s biography of a woman ‘Twelve Year a Whore, five times a Wife (whereof once to her own Brother), Twelve Year a Thief, Eight Year a Transported Felon in Virginia’ was also banned as indecent. Its allusions to sex outside of wedlock, adultery, prostitution and crime were seen as too scandalous for the population of America during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, despite Moll learning the error of her ways and dying a penitent, pious woman.

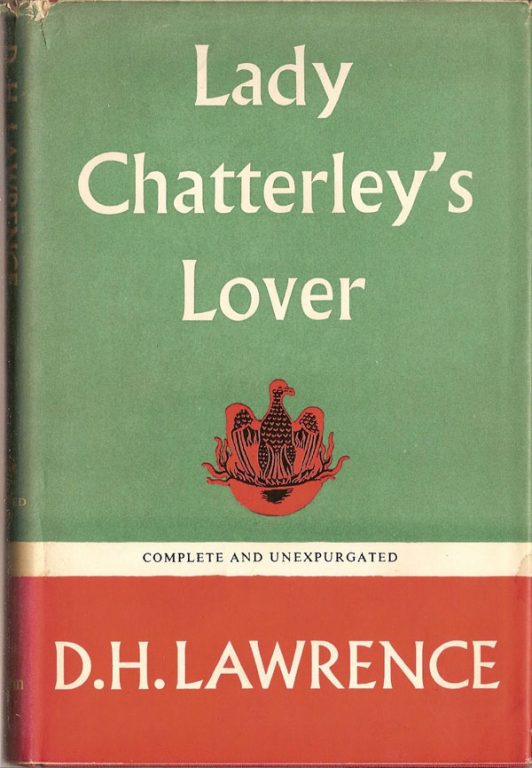

- Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence. The book caused the US Senator Reed Smoot to declare, ‘I’ve not taken ten minutes on Lady Chatterley’s Lover, outside of looking at its opening pages. It is most damnable! It is written by a man with a diseased mind and a soul so black that he would obscure even the darkness of hell!’ This was not the first of Lawrence’s novels to be banned, and he was furious to find yet another bit of his writing suppressed by the censors. In 1928 he wrote a letter to Morris Ernest – the attorney who would go on to successfully vindicate Ulysses from obscenity charges in 1933 – to vent his anger:

‘Our Civilization cannot afford to let the censor-moron loose. The censor-moron does not really hate anything but the living and growing human consciousness. It is our developing and extending consciousness that he threatens – and our consciousness in its newest, most sensitive activity, its vital growth. To arrest or circumscribe the vital consciousness is to produce morons, and nothing but a moron would wish to do it.’

- Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs. The 1962 edition was banned immediately in Los Angeles and Boston due to its obscenity, and publishers were harassed for their involvement in its American edition and the original French publication. The book made it onto bookshelves in 1966, after a lengthy court case in which both Allen Ginsberg and Norman Mailer declared it a masterpiece. Mailer told the court:

‘The man has extraordinary style. He catches just a little of the beauty. I think he catches the beauty, at the same time the viciousness and the meanness and the excitement, you see, of ordinary talk, the talk of criminals, of soldiers, athletes, junkies. There is a kind of speech that is referred to as gutter talk that often has a very fine, incisive, dramatic line to it; and Burroughs captures that speech like no American writer I know.

He also – and this makes it impressive to me as a writer – he also has an exquisite poetic sense. His poetic images are intense. They are often disgusting; but at the same time there is a sense of collision in them, of montage that is quite unusual. And, as I say, all this together gives me great respect for his style.’