The brown hair was frizzy around her neck, and around her forehead there was some frizziness. Her ears held six piercings each and six earrings each, twelve. Her top lip was full, and her nose came down almost to the full top lip, though the bottom lip was less full. Her profile was frozen, and the toothpick between the uneven lips, a branch between the lips. A blue plastic bag was wrapped around her neck, billowing behind her like a cape. Her top came so low it seemed as if she was wearing nothing except that blue plastic bag.

The diner window showed her profile, her neck, the plastic bag behind her, the collarbone. The top was concealed by the wall and the restaurant siding. Her face was in the window. The hot sauce was being poured over everything, the fries and the chicken, the grits and the grapes. The maple syrup was being poured over everything, over the fried meat.

The waitress carried a jug of water. This woman drank gallons of water the way her skin was. A swan. On her head a hive. When she laughed her head bent back.

And her eyes were everywhere, her eyes traveled, they caught the whole room, and she made eye contact with the family across from her, with the waitress and with the manager. She ate cherries and grapes two at a time, spitting the seeds into an ashtray. When she ate she let the toothpick fall to the table. On her tongue there was a tongue ring and a cherry pit. She wore gold hoop earrings.

Around her the diner was falling apart; the walls were stained. The counters were stained and the floors were stained. The aprons were stained with sauce and grease. The forks were not thoroughly cleaned. The flowers were drooping and dying.

She dipped the tip of the cloth napkin (blue and white, checkered) into the glass of tap water (which contained lemons and limes, sliced grapefruit), and she wiped her top and bottom lip. She kept the damp material over her mouth, her eyes moving all around. For a while her mouth was unknowable, covered by material. Near the glass of water, a cup of iced coffee or iced tea, a brown liquid.

Next door to the diner was the barbershop with its wood paneling and its poster of men. The poster showed men with different hairstyles – some of them were looking up, some were looking to their right with their profile showing, or holding their chins down. On some the faces couldn’t be seen at all, just the backs of their heads and the work of the clippers. Some hair was shorter, some longer. Twenty-eight styles total. A calendar on the wood-paneled wall showed October, with a corner folded over to conceal the year.

When she finally removed the napkin from her lips, crumpling it all up and placing it back on her lap, she used her hands to speak. Her wrists were framed by the dirty window, and she rotated them around. She held up two fingers, then four, seven, she clapped her hands together, punched one hand into the other, the right punching into the open palm of the left, as if to emphasize something. Open, punch, wave, punch, clap, punch. Then she rubbed her hands together, as if moisturizing them or disinfecting them, caressing, and the rings were eight, none on the thumbs. She moved so often and so thoroughly that her body became a blur, the fullness of the top lip couldn’t be detected, the blurry bun, the nose, the neck. She looked down at her hands.

A blurry child grabbed onto her neck. The blurriness couldn’t hide the fact of that small being. He grabbed at her from behind. This woman was generous with him. The child’s ears like her ears, the top lip the same, full, the frizzy hair. There had been placenta between them. They each wore a blue plastic bag around their neck; their backs were made of blue plastic.

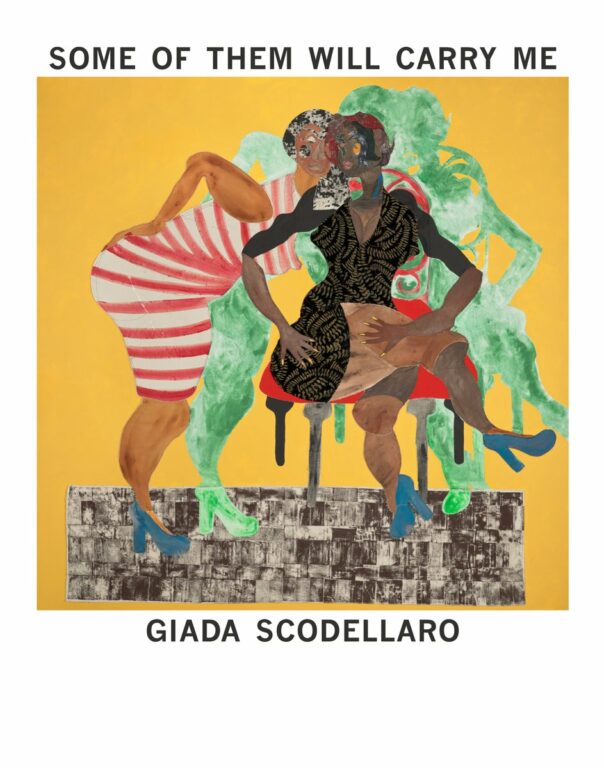

Image © Lisa Ann Yount