At the state-funded Orthodox Jewish primary school I attended – in most other ways a modern, lively school – the morning prayers contained separate lines for boys and girls. ‘Thank you, God,’ we all said together, ‘for not making me a slave.’ Then we divided. ‘Thank you, God,’ said the boys, ‘for not making me a woman.’ ‘Thank you, God,’ said the girls, ‘for making me according to Your will.’

It took me a long time to understand what was troubling about those words. It took even longer to see that there was nothing wrong with me for being troubled, and longer still to take action to protect myself from their impact. And I sometimes forget how far that journey has taken me.

Recently, the Brooklyn-based Orthodox Jewish Yiddish newspaper Di Tzeitung caused a minor kerfuffle when it emerged that it had published a photograph of Barack Obama and his staff monitoring the raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound but had erased the women – Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Director for Counterterrorism Audrey Tomason.

Twitter was full of shock and outrage. Di Tzeitung issued an apology. And I was surprised by the secular world’s surprise. Because I forget, even now, that most people don’t know. This picture didn’t shock me at all. I’ve seen this, and worse, in Orthodox Jewish newspapers and newsletters since I was a child. I’ve seen photographs where a woman too awkwardly placed to be erased had been given a Photoshopped hat and beard. I’ve seen photographs in which all the women’s faces were pixellated, all the men’s faces clear.

Like the people who made a programme trailer misrepresenting the Queen and got into trouble for it, it’s not that this behaviour is new: it’s that they’ve finally done it to someone who matters. In fact, I find I actually love that edited Obama photo, because it’s finally cast a light on the misogyny of the Orthodox Jewish world I grew up in.

Orthodox Jews don’t do ‘honour killings’. They don’t set women on fire or approve ‘punishment rapes’ or declare a husband’s right to beat his wife. I’m profoundly grateful for all of this. But that photograph illustrates perfectly the kind of misogyny that exists in the Orthodox world: the erasing of women from public life.

The excuses Di Tzeitung gives have a familiar ring to me. ‘Jewish laws of modesty are an expression of respect for women, not the opposite,’ they say. I remember that one. I’m afraid this is a lie. Jewish laws of modesty are an expression of the supremacy of men’s experiences – that women’s need to be seen and heard is less important than men’s need not to be in danger of feeling aroused. They say they ‘believe that women should be appreciated for who they are and what they do, not for what they look like’; one wonders why, if this is such an expression of honour and respect, it couldn’t also be extended to men. Finally, Di Tzeitung says it ‘should not have published the altered picture’. What they mean, of course, is that if they’d known they couldn’t alter it, they wouldn’t have published it at all.

As an Orthodox Jewish (or, in the parlance of that world, frum – the ‘u’ sounds like the ‘oo’ in ‘soot’) girl growing up, one is taught from an early age that one ought not draw men’s attention. Dress codes forbid such items of clothing as: any skirt that comes above the knee, tops that do not cover the elbows (too arousing), T-shirts with images on the front (in case they cause a man to look at your chest) and, I kid you not, patent leather shoes (in case they should happen to reflect the upper legs – the frum equivalent of an up-skirt shot). It’s about more than just covering bodies, though. Orthodox Jewish women may not speak in public to a gathering including men. Imagine what could happen if a man watched you speak and found he fancied you!

And the rules are socially enforced. I remember as a twelve-year-old, at Saturday afternoon youth group, I was singing under my breath while preparing a salad. ‘Kol isha,’ said one of the boys, cocky, his yarmulke at a rakish angle. I didn’t know what he meant. ‘Kol isha erva,’ he repeated, ‘we learned it in school. A woman’s not allowed to sing in front of a man.’ Kol isha erva means: ‘the voice of a woman is obscene’. I have been struggling since then to rid myself of the sticky strands of that moment.

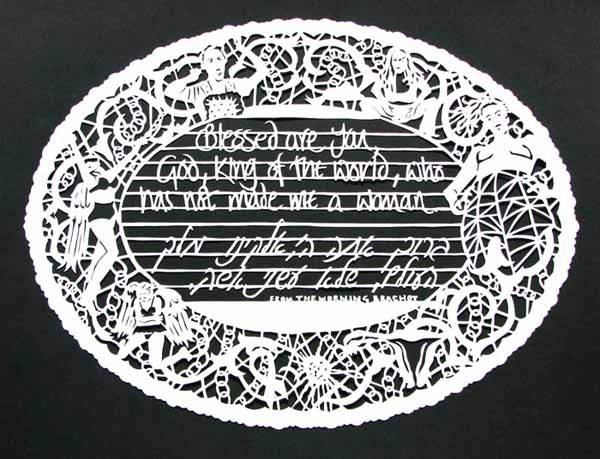

Artwork by Jacqueline Nicholls

I love the work of London-based Orthodox Jewish artist Jacqueline Nicholls, who takes misogynist texts from scripture and decorates them with images of sexual, rebellious, powerful women. One quote she pulls out is exactly the reason that Di Tzeitung erased the image of a sixty-three-year-old US Secretary of State. A virtuous woman, say the rabbis in Talmud Sota, is one who says to God: ‘May it be Your will that I not cause men to sin.’ It’s a sin for a man to think about having sex with any woman but his wife. Looking at any image of a woman, says the ultra-Orthodox world, could have this effect. So they must all be removed.

Erasing women is about the unquestioned assumption that it is men’s spiritual lives that really matter. That the effect on a woman of being told never to draw attention to herself – the slow corrosion of one’s sense of self, the undermining of one’s confidence in one’s own value – is unimportant in comparison with men’s lives and experiences. Nicholls says: ‘Like an alcoholic blaming the bottle of wine for their own inability to have only one or two glasses, the men blame the women for tempting them, for their lack of control.’ Because there is also the equally horrifying and demeaning assumption buried in there that men’s sexuality is bestial and uncontrollable. I imagine this has a bad effect on men. I know it’s caused a lot of fear in me.

It’s not just about sex, of course. Orthodox women are not allowed to learn the same texts as men – we’re too stupid to understand them, is the line. ‘The mind of most women is not disposed to study, and they will turn the words of Torah into words of nonsense due to their limited understanding,’ says revered thirteenth-century Rabbi Maimonides in Hilchot Talmud Torah. Such texts wouldn’t be a problem if Orthodox Jews were able to say: ‘This Torah, these interpretations, made sense in their historical period, but are outdated now.’ But the Orthodox world cannot say this: all rulings, all Torah laws, are made for all time.

Orthodox Jewish women cannot become rabbis. Unless they can, they will never be involved in creating the laws that rule their lives. This is the Orthodox Jewish equivalent of getting the vote. And although one or two Orthodox rabbis are trying to push forward on this issue, those who try to ordain women have been threatened with excommunication by other, more influential authorities.

I remember a conversation I had with another of those calm, self-assured, frum boys, this time at university.

‘Women can’t be rabbis,’ he said. ‘They can’t understand Talmud in the way a man does, they’re too emotional.’

‘I know it’s not true,’ I said, trying not to become angry, because that would prove how over-emotional I was, ‘I know, like cogito ergo sum, because I can observe my own understanding. I know it’s not true.’

‘The rabbis say’, he said with finality, ‘that if they tell you night is day and day is night, you must believe them.’

Is it a symptom of weakness that I still regret, a little, that I was never able to crush my own sense of truth and falsehood enough to accept this? Is lack of capacity for self-deception the same as lack of faith, and if so, is it to be regretted?

I felt very alone at primary school, mouthing that line, ‘Thank you, God, for making me according to your will,’ while the boys proudly thanked God for making them a man. I was vaguely aware by the time I reached nine or ten that something disturbed me about these lines, but didn’t realize how grotesquely offensive they were until I included them in the novel I was writing, Disobedience. When I handed pages from the novel out to a workshop at University of East Anglia, one woman told me that I really shouldn’t make things like this up about my faith, and found it hard to accept when I explained it was really true. Another workshop participant had scrawled, ‘This makes me want to punch someone in the face’ over the page.

This, I imagine, should be the point where I call for a ban on state funding for religious schools. Or a ban on religious life that erases women. Or a ban on religion altogether.

But banning solves nothing. And some of the worst oppression isn’t external but internal.

The most offensive talk by a religious authority I ever attended was during my most frum phase. I was really trying to square my religion with the truth I knew in my head. I went to classes, I prayed every day, I tried hard to make it work. And then I attended a talk and something broke in me, because I knew that if this was what it meant to be frum, I could not bend myself far enough to accept it. The subject was: ‘The beauty of a woman is in her silence.’ And the authority who explained this inspiring thesis to thirty young women was herself a woman.

What is going on in the head of a woman like this? I was never quite able to get myself to the point of believing it, but I gave it a good try and caught hold of the edge of that feeling. It feels very safe, curiously, given what an unsafe position it really is. It feels like abandoning oneself again to childhood, ceasing to feel that there’s any need to change anything in the world, relying on someone else – a husband, a father, a rabbi – to tell you what to do. It’s comforting, and comfort is seductive, especially for young women for whom the outside, Western, secular world seems beset with problems and objectification. Some women choose to self-subjugate. And the reasons for those choices are complicated and not easily untangled.

If someone had tried to ban me from being an Orthodox Jew I’d probably still be one. Not because I’m a terrible contrarian – although I am – but because change happens in tiny incremental steps, because you have to feel welcomed before you’re able to change your values, because you need that space to think and explore and consider. I couldn’t have run out of the talk that day and said ‘I’m no longer an Orthodox Jew’. It’s taken years – I probably first started questioning in my teens, but I was over thirty when I finally felt able to say, ‘I’m no longer an Orthodox Jew.’ It’s taken thought and therapy. It’s taken writing a novel. It’s taken finding new friends and difficult conversations with old ones, and with family.

This, among other reasons, is why I could never support the banning of the burkha. It is a feature of the patriarchy to be more concerned with what women are wearing than with what they’re doing or saying or thinking. If a woman is oppressed on the inside, it doesn’t much matter what she’s wearing. You can’t change minds by changing outfits. If we really want to set women free – rather than just relieving ourselves of the burden of having to look at what we imagine to be oppression – we need to allow women to engage in dialogue with liberal, secular values wherever they happen to be, whatever they happen to be wearing. Banning clothing is a way of saying that we don’t trust in the power of our own values to change minds that are open to them. But those values are powerful, and they can and do change minds.

And there’s this as well. Foolishly, ridiculously, I set out as a teenager for the shores of Western secular culture like a refugee, hoping to land in a place where all the problems I’d fled were now solved. Equality under the law, I fondly imagined as a fourteen-year-old, would surely mean that total equality in every field would come about before I ever entered the job market. I have, as you can imagine, been bitterly disappointed.

So Orthodox Judaism has made me a better feminist. Coming from a world where the women are erased makes me realize how much this happens in the Western secular world too. It makes me stare at the unedited version of that Obama picture and think: Really? Only two women? One of them at the back? Among eleven men? What are you people, Orthodox Jews?

Artwork: ‘R. Hisdah’s Daughter’ by Jacqueline Nicholls