I am the wolf

Who does not sleep

I’m not frightened of you

You are frightened of me.

– Grégoire Solotareff

The provision of safe sleeping arrangements for everyone is a social indicator of the birth of the state.

Historians such as A. Roger Ekirch describe how, little by little, public lighting and night patrols were organized first in cities, and then throughout the rest of the country. Street lighting on main roads became a political initiative in the Middle Ages. It was a matter of guaranteeing that everyone could sleep safely, but also of ensuring that people slept, or at least stayed home. Before the industrial revolution, night work was illegal in the majority of businesses. Every vagrant was suspicious, every female out walking was a witch or a prostitute, while the patrolling officers themselves were required to keep their eyes open. In a sense, not-sleeping was the monopoly of the state. Anyone who didn’t sleep was feared or frowned upon.

Open 24 Hours

The ascendancy of electricity accelerated the streamlining of cities and metamorphosed the relationship between human beings and the night. Once Electra is domesticated, citizens can, and must, work, regardless of the position of the sun in the sky.

Jonathan Crary, in his book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, deciphers how capitalism has succeeded in commodifying all our basic needs: light, heat, water, food, housing, sex, and even friendship. But it still has trouble expropriating sleep. It therefore permanently illuminates the night so that the conditions under which frenetic production takes place are a form of generalized insomnia. The watchword from now on: open twenty-four hours.

But now it is not so much light stopping us from sleeping as nonstop connectivity. ‘We are dictated to by the news,’ said Gilles Deleuze back in 1980. Drawing our attention to one conflict rather than another, to a particular human-interest story rather than a particular event – that’s what constructs our ‘current affairs.’ The instruction is given using verbs intransitively: a news item will ‘be of interest,’ a banking term; we might even be ‘mobilized,’ a military term. The broadcasting and receiving of signals has become a sort of modern way of breathing, on a planet that would have to stop turning in order for us to continue our social messaging ad infinitum, without nocturnal interference.

Sleep then becomes a structural attention deficit, a systemic anomaly in humans: ‘Microsoft has revealed it took five hours to acknowledge lengthy disruptions affecting European customers . . . because the task of informing customers relied on a US-based incident manager, who was asleep at the time.’ I’m reading this in April 2020, between two news stories on the coronavirus: ‘When incidents involve customer request failures . . . we have automated tooling that starts an incident and loops in both a DRI (designated responsible individual) and what we call a PIM (primary incident manager),’ explains Chad Kimes, director of engineering at Azure. ‘While the DRI was hard at work understanding the technical issues and looking for potential mitigations, the PIM was still asleep.’ ‘To sleep’ or to be ‘on sleep mode,’ the same vocabulary for humans and machines, the same requirement for alertness and efficiency: we no longer know who is automated or who should be.

Because of this injunction to be not only attentive but responsive at all times, ‘sleeping is for losers,’ according to Jonathan Crary’s diagnosis. When Trump tweeted at three in the morning, he presented the image of himself as awake, alert. The strongman, with machine-like energy, is active while we’re asleep. Could we imagine Big Brother sleeping?

And yet most of us need to sleep. Joshua Trump, a young eleven-year-old American invited by his homonym to the State of the Union Address, was called a hero by anti-Trump followers for having fallen asleep during the sacrosanct spiel. And on the planet Shadok, even the feet-on-top Shadoks, who stopped the planet from falling, had to sleep from time to time, ‘so, when they were on their backs, their feet no longer supported anything.’

The liberal economy burns up its human resources the way it does coal or oil. Work structures produce more and more burnout, workers are ‘consumed.’ Vulcan, the god of work and fire, and his forge, torment us even in our beds. ‘It seemed to him as if a heartless blacksmith, a lugubrious outrider, a cruel cyclops was working his entrails, hammering away at his fragile skeleton,’ wrote Paul Gadenne in ‘Insomnia.’

When my father oversaw maintenance at the foundries of Mousserolles, he was in charge of the smelting and was often woken in the night, whenever one of the machines broke down. Which did nothing for his sleep, nor, alas, for his tobacco consumption. Looking at a photo of himself at work, in Bayonne in the seventies, he told me, he was ‘inside a continuous oven that had broken down, trying to work out the problem and how to repair it. Very unpleasant for a claustrophobic person.’

In the past, before the word burnout existed, we talked about being ‘overworked.’ The solution was to stop work temporarily. Then, under the pretext of yet another ‘crisis,’ this time the European fuel crisis of 1974, new work arrangements transformed workers into furnaces that were never turned off longer aimed at monitoring personnel but rather liquidating them. With Management and Performance Review in power, work was accompanied by analyses of work, with the paradoxical aim of increasing productivity: reports, tables, spreadsheets, activity charts, logbooks, news lists, accreditations and recommendations, protocols and procedures, orientation booklets and best-practice guidelines, client files, patient records, student-assessment records, quality-assurance processes, reviews, entrepreneurial- potential self-assessment forms . . .

On September 21, 2019, Christine Renon, ‘exhausted principal’ of the Méhul de Pantin school, wrote a letter addressed to the Ministry of National Education before throwing herself from the roof of her school. On the three closely written pages where she detailed the mountain of absurd tasks she was required to complete, the lists of reports on goals and objectives, ‘prospects’ that were always in the future (and it is as if, as she wrote, she didn’t know that at the end of her letter she would kill herself, as if writing it led her to this harrowing conclusion), she also notes ‘the prospect of having to wait to see my doctor about the cough that has prevented me from sleeping for three days.’

‘In the Penal Colony’ is a short story written by Kafka two months after the start of World War One. A man is going to be executed. What was his wrongdoing? ‘He is duty bound at the stroke of each hour to stand up and salute at the door. To be sure, hardly a daunting responsibility, but a necessary one, as the man must remain alert both as a guard and servant. The captain last night wanted to confirm that the man was doing his duty. At the stroke of two he opened the door and found him rolled up and fast asleep on the floor.’ Inscribed on his body by a machine, the sentence ‘Honor your superiors!’ will be etched more and more deeply, until he dies.

Networks and Transparencies

Stefan Zweig, two weeks after the start of World War Two: ‘From now on, an endless network covers the world, all day and all night.’ No one is alone in their bed anymore. Each individual knows that ‘thanks to our new methods of spreading news as it happens, we have been constantly drawn into the events of our time . . . Incidents thousands of miles away came vividly before our eyes. There was no shelter, no safety from constant awareness and involvement.’

The networks crisscross our sleep, the rhizomes grow in our brains. This new environment has spread steadily, speeding up. There is no escape from the news. We are a community filled with anxiety. We are as global as bubbles. And we also like this instantaneous medium that is now so familiar. We order American-made objects that arrive in our European letterboxes, sent from addresses in China. We see them on our screens and they materialize in our apartments. The annihilation of space by time: Marx predicted it, Amazon enabled it. And in the mid-2000s we saw people living in Brisbane, Mumbai, Lagos, or Buenos Aires, pixelating all at the same time on Skype video conferences. Our still-faltering communication systems, with flickering images and intermittent audio, gave those years their old-world tone. During lockdown, the use of these apps multiplied exponentially – FaceTime, Zoom, Teams, Jami, Discord, and others. Discordia, daughter of the night, in Homer’s words.

And in the general conversation between meridians, in the here-and-now straightaway, at least one of the participants will not have slept. In their time zone, the call will have cut into the time normally devoted to sleep. The call was just one of many demands hovering in the air: everything can happen everywhere and all the time.

Instead of being enhanced by the transaction, we are tormented by what is lost.

‘There is less sleep in the world today,’ wrote Stefan Zweig. There is also less of our body, despite the proliferation of human beings on the planet. And the body, it seems to me, is sleep. Studies remain inconclusive, with contradictory results, about whether we slept or not during lockdown. When the coronavirus paralyzed Wuhan, Xiaoyu Lui, who lives in the center of the city, said in the week of January 31: ‘My neighborhood is almost deserted, and I am sleeping unusually well.’

The writer Fang Fang, also from Wuhan, kept a blog, translations of which quickly traveled round the world. On January 29, she confesses to sleeping until midday every day – as usual, she clarifies, but now without ‘blam[ing] myself.’ But on February 11, she adds, ‘for more than 20 days now, I have been relying on sleeping pills to fall asleep each night’ – that is, since the beginning of lockdown. Bombarded by anxiety-inducing news, by rumors and propaganda, she is also on the receiving end of violent attacks on an internet that is censured by the party and swamped by ultra-nationalists: her solitude is overcrowded.

Whether we’re locked down or not, it’s clear that, even in our bedrooms, space is annihilated by time. Do you have your own room? All sorts of devices surround you. Electromagnetic waves circulate. Diodes keep their eyes peeled. No matter how often you put your device on ‘airplane mode,’ on ‘ghost mode,’ on ‘do not disturb,’ the world – at your fingertips, just like in the ads – demands that you stay present. In the depths of insomnia, you go online again. Your pupils contract in the blue light of the screen. An artificial dawn. You read your text messages and comments, you look at and listen to images, you discuss, perhaps you add a comment and you like, you look at things that are your business and that others are perhaps making it their business to look at too.

Those born before the 1990s remember boredom. In order to live, you had to get out of your bedroom at all costs. We all know Pascal’s refrain: ‘The sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.’ How guilt-inducing. We don’t want to stay in our room. The lockdowns proved that to us. And, even if we wanted to, that room no longer exists. It has become an online space, where boredom has been replaced by impatience. In the nostalgic Pascalian room, it was possible to be an isolated speck on a little-known planet. And it was possible to remain private, opaque. These days, we are summoned by planetary time; it travels through us. We are compelled to participate. Even in the bedroom, that famous rest is difficult to achieve. Time spent in the bedroom is itself evaluated, judged, measured, approved or disapproved, according to the demands of work, communication, or health. An hour to yourself? It sounds like an advertisement for a leisure center or a body treatment. The walls of Virginia Woolf ’s marvelous room of one’s own, that absolutely private space she dreamed of for women, have been knocked down, regardless of gender, regardless of style.

The walls, porous to the world, become as transparent as in the visionary nightmare of Yevgeny Zamyatin, Orwell’s precursor. In his novel We, the totalitarian city is made entirely of glass. At 10.30 p.m., everyone has to sleep, blinds up (they are only lowered for authorized sexual relations). But citizen D-503 can’t sleep. ‘I argued with myself: At night numbers must sleep; it is their duty, just as it is their duty to work in the daytime. Not sleeping at night is a criminal offense.’ The first symptom of rebellion in this supposedly transparent subject is insomnia.

And when he doesn’t sleep, he dreams, he discovers the hypnagogic state. ‘My bed rose and sank and rose again under me, floating along a sinusoid.’ ‘You’re in a bad way! Apparently, you have developed a soul!’ announces the doctor.

Fifteen years later, in the Germany of the Third Reich, the psychiatrist Charlotte Beradt collected seventy-five-odd dreams in a book that became famous. Like this nightmare from a forty-five-year-old doctor: ‘Suddenly the walls of my room and then my apartment disappeared. I looked around and discovered to my horror that as far as the eye could see no apartment had walls anymore. Then I heard a loudspeaker boom, ‘According to the decree of the 17th of this month on the Abolition of Walls.’’

A forest full of supposedly wild beasts surrounds the glass city in We. A wall protects the city from all that disgusting freedom. D-503 is going to make a break for the forest.

Insomnia and Forests

During the expansion of the modern world, the forest has become a place of refuge and a place to avoid. You escape to the woods and you get lost in the woods. The forest is a world of fairies and of danger, a glade outside time, a maze. And in this expedition beyond the walls, perhaps a different type of sleep awaits us, plantlike.

We know about the sleep of trees. As children we join in autumn rituals. The sap descends, the leaves fall, we collect them and play in the dancing wind. Childhood amounts to ten autumns. If winter is the trees’ nighttime, in spring they wake from their vertical sleep. They’re not being reborn. Children understand that quickly enough. A tree without leaves is not a dead tree, but a tree that is sleeping, waiting quietly for winter to pass. In equatorial forests, trees are insomniacs. Their leaves grow incessantly and fall when they fade, constantly regrowing in all that green wakefulness. We cut down these thousand-year-old forests and insomnia spreads. The trees release it throughout the world like an evil gas, and we are being asphyxiated.

One of our years is the equivalent of a day in the life of a tree. A growth ring equates to one night in a tree’s life.

The Chernobyl exclusion zone, June 2018: the forest is everywhere. The trees have a sci-fi exuberance about them. Their roots raise staircases and make walls collapse. New growth is shooting through what is left of the asphalt.

There are birds everywhere. Foxes have the run of the place. Bears and wolves have returned from Belarus. I have that forgotten feeling of brushing away swarms of little flying creatures from my face. Enormous and normal swarms of insects. Clouds of dragonflies. Airborne plankton. Childhood memories of being in the country, the humming noises, and those droves of creatures in the grass, in the trees, on silken threads, in webs, in cocoons.

Life. A few steps to one side – the curiosity of Homo sapiens is like that of a fox – and our dosimeters start beeping like crazy: invisible ‘spillages.’ Especially under houses, in the dry grass. The radioactivity ran off the roofs that were hosed down after the 1986 catastrophe.

In 2020, for the whole of the month of April, historically dry because of climate change, this forest burned, exposing Ukrainian firemen to the double danger of fire and radioactivity, while the rest of the world, locked down by coronavirus, remained relatively indifferent.

(I’m trying to imagine the effect that sentence, out of science fiction, would have had on me as a child.)

‘I suffered from insomnia and had lost my zest for life.’ In his Journal Written at Night, the Polish writer Gustaw Herling-Grudziński invents a dystopia where an insurance agent, ‘in charge of the forestry department,’ makes an annual trip to the Sistine Chapel to revitalize his soul; but now that the cigarette lighter has been invented, the forests go up in flames. Everyone stays up all night on Saint Peter’s Square. A whole new group of people set up camp and chant around small fires. Next the Sistine Chapel burns down.

The forest has been with us forever, ever since we became that species with upright posture. And before we stood up, we were no doubt hanging on by the first human hands. The opening of The Divine Comedy: ‘In the middle of our life’s journey, I found myself in a dark wood, where the straight way was lost.’ Even Dante descended from the apes. In line 11, he has no idea how he entered the dark wood, because he was ‘full of sleep’; in line 28, he rests a bit; in line 29, he continues his descent (this forest is a ravine); in the next lines, all sorts of animals bar his way; in line 62, Virgil appears: Phew, here’s the guide. The whole journey is nothing more than a long negotiation between sudden sleeps and unforgiving insomnia.

In the middle of my life’s journey, from what I could estimate as the forty-something I was, I was blocked two-thirds of the way through a novel. For the readers who may be interested, it was precisely at the sentence: ‘And which seer could read her future, when her entrails were uncoiled in the labyrinth?’ Without a seer on hand, I had no choice; I had to follow my characters where they took me: into the forest. The real one. The ancient, virgin forest that had grown without the presence of human beings. I had to enter that forest, I who had always stayed back cautiously on the edge.

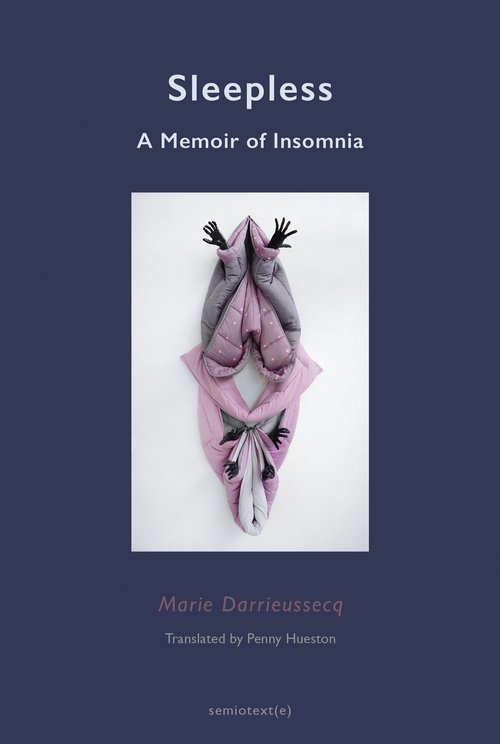

Image © MB