I remember the merciless sun in Tirana, the long summers, the old men with faces corroded by the spittle of the light, and I remember the litter on the streets and piled up at the edges of houses, children playing among the rubbish, women burning trash in the streets, I remember the black, heavy reek of melting plastic, the metallic stench of the sewers like the air inside a damp, rusted container. I remember the sense of nausea upon grabbing my crotch as girls walked past, because that’s what my friends did, the anxiety when I didn’t cry though I wanted to, because I knew that men weren’t supposed to cry, and I remember the dizziness when my parents began talking to me about marriage and continuing the family line. I remember everything, as though it all happened barely a moment ago, and now I know that the farther away from it I have come, the more content I am and the more rarely I think about where it all began.

My mother once said that people think with their brains but feel with their hearts. She was crouched on the bathroom floor washing tea glasses that were so delicate she had to clean them with her bare hands. You’ll feel it when you fall in love, she said with her back to me as she submerged a foam-covered glass in the dishwater. Your heart will feel it, and after that nothing else will matter. When you meet the right woman, you’ll notice that you won’t think with your head. Then you’ll marry her, you’ll have children together and look after us, she said almost in passing, as though she knew precisely what my future would hold.

I have shown her words to be a lie, for throughout my child-hood I hated myself with all my heart and mind, and I don’t think I ever really loved anyone. I hated how obsessed I became with studying, how I walked, the sound of my voice, the smell of my sweat, and the color of my urine, hated how I starved myself, hated the binges this self- imposed regime brought about, and how woefully I would weep after bingeing. I wanted to be like the people I’d seen on television, wanted to look like people in the West with clean skin and neat clothes with no clumps of fluff, no signs of wear and tear. I wanted to look like a movie star, I wanted skin without any imperfections, without a single furrow etched by worry and the sun’s rays.

I hated the things I could never become and what I therefore wished on those close to me. I wished a war would break out, wished my homeland would be attacked, wished that someone would drop an atomic bomb in the middle of Tirana, killing every last inhabitant. I wished a volcano would erupt, engulfing everything in lava. I wished my family would die, my friends too, everybody I knew, because only that way could they never follow me wherever I went.

I was ashamed of my family, especially my mother, who couldn’t read or write and who didn’t seem bothered by that fact. I was ashamed of my sister and the inability of my aggressive father to deal with his emotions in any other way but through violence. Perhaps this was the reason it was so easy to wish a dreadful fate upon them. In the end, their continued existence was immaterial to me, I wasn’t that interested in them, and I didn’t consider them special in any way. They simply existed; the fact was they lived in the same apartment and made sure there was always something to eat. They were on the periphery of my life, like music you can’t hear properly over the noise of the traffic.

I couldn’t stand the way people spoke about the past, Albania and the Albanians, as though there was something in our history that our future could never equal, as though there was something great and all- encompassing in our nationhood, as though Hoxha was the most important figure in our history, as though it was a privilege to have lived in that world, in the greatest lie known to man. I couldn’t stand the way people talked about love and marriage, of a whole life planned out in advance: a chosen wife and a chosen husband, at least one son, the gleam of honor always at the back of the mind, wrapped around a person like a set of clothes.

I was nine years old when Hoxha died. The most visible difference from the previous day was that women were weeping in the streets and some of the men were walking around in celebratory groups, others arm in arm as though they were keeping one another upright; they had taken off their hats, holding them in their hands like bricks, and dragged their feet, ghost-like. I could almost make out the grief in their gait, some furious, some overjoyed, and I was afraid; everything felt, tasted, sounded so clear, there was a feeling that something irrevocable had happened, the sense that the whole city was attending a wake, and it felt as though the earth shuddered beneath my feet, and I imagined that deep under the streets lay the heart of the city, an enormous, palpitating heart pumping to an arrhythmic beat of its own and with all the constituent parts, its chambers and blood vessels the twisting sewer system, winding streets and alleys, the mountains surrounding the city like lungs around the heart.

After Hoxha’s death, many people, my parents included, believed they were finally free. We bought a new television, a new refrigerator, then another new television, and before long my father wanted new furniture too. My father began praying five times a day, and my parents started talking about God. Suddenly the entire world that had been built, the world in which he and my mother had lived happily, no longer existed. In its place was a new life, a new tomorrow where heavy rainfall had washed away the past.

*

When I first arrived in Italy, I looked for a police station and told the authorities that I belonged to a sexual minority and that for this reason I could not return to my homeland. They beat me, I said. I’m homosexual, it’s very hard and I’m very scared, I continued, because I knew this was my ticket into the country. The woman dealing with my case looked at me, and I guess she used those few seconds to imagine what it would be like if she fell in love with another woman and wanted to stand next to her beloved, the way she should, but couldn’t because she knew that a large crowd of people would beat her to within an inch of her life.

I’ll kill myself if I have to go back there. Albania is no place for me, I continued solemnly, after which she doubtless thought about all the stories the Albanians trying to get into the country told about their past. They were prepared to say anything to secure a residence permit and stay in the country, anything at all except the one thing I had just told her. I’ll do what I can, she said, looking at me with compassion.

A few months later I was granted political asylum, then a few years after that I was awarded the permanent right to remain and an alien’s passport. After that I moved to Rome and decided to forget everything that had happened to me, I erased my name from my memory, forgot my former home and deceased relatives, people who once walked by my side but who eventually fell by the way. I forsook my hopes and dreams, for there was nothing good about my past, there was nothing in the past to which I wished to return or that I wanted to tell people about, and nothing in my past had helped me get where I wanted to be.

I decided to create new hopes and dreams, find people who would become a part of me, and who with time would become my new family. I decided to take hold of each and every day, every moment, as though it were a unique opportunity, and I repeated to myself that in this country every day is a new chance to be a new person, to be exactly the kind of person I’d always wanted, because I had blindly believed that one day, before long, everything would take a turn for the better, the way books and movies teach us about life, and I would step into the spotlight, I would be seen. I believed that at some point this simply must happen, because there was nowhere I could return to. I no longer had a homeland.

But how can you go about starting over, working in a language you don’t understand? What is the best first step? How can you establish a relationship with someone if you want to deny your past, your nationality, if you don’t want to tell anyone anything about yourself, if what you most want to do is forget where you’ve come from, wipe your past away like a smudge of dirt from a shoe? In a situation like that, what choices do you have?

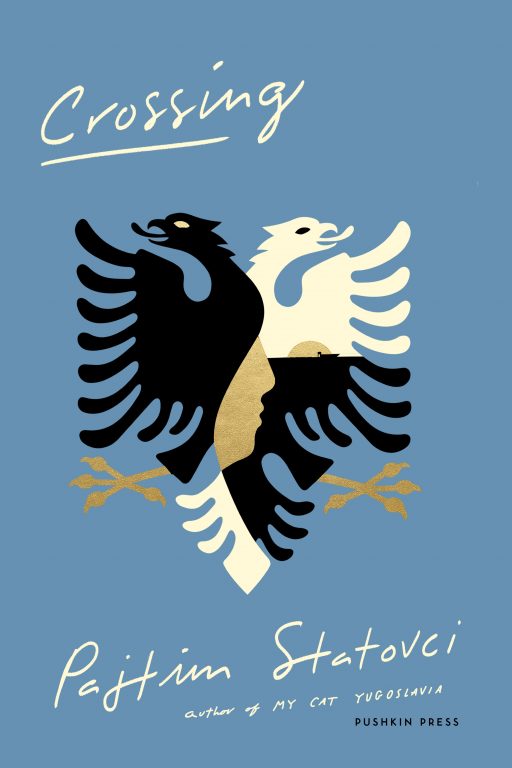

The above is taken from Crossing by Pajtim Statovci, translated from the Finnish by David Hackston and published by Pushkin Press.