Like everyone, I too am made of language. I remember how I came into being like it was yesterday: as a single sentence, head to toe. My mother told me she felt the seed take root the instant I flashed like a spark in her womb, when my father whispered into her ear, ‘A girl.’ I felt an unbridled sense of gratitude as I listened to this story, felt the joy of being beckoned lovingly into this world. From that day forth, I gained a newfound respect for all the creatures I encountered in the world, each bestowed with its own unique significance. That sentence of hers had planted itself in my spirit to such a degree that I was carried away imagining my mother during her pregnancy, imagining her craving moonlight and my father gathering moonlight for her accordingly. To imagine was, if nothing else, to hold my place in the world.

And yet, there was another sentence: ‘They slaughtered us,’ my grandmother once said. We just sat there afterward, our sighs resounding. She didn’t say anything else, didn’t offer any details or explanations. This time, a historic pain, incompletely mourned, began etching itself into my bones.

What’s interesting is that up until that moment, I had no social identity, no nation, no homeland, but I did have a world. Within the meandering rift between the world and my parents, I had been living in a timespan unsullied by others. Each and every word was to me a fleeting, limpid, lyrical sound. But after I heard ‘they slaughtered us,’ all the words I knew began to harden. The fearless fantasies my imagination nourished were suddenly stained by the injured expressions of an outsider. It was as though I was a fruit with two seeds and a bitter rind. From one seed sprouted words to consecrate what it meant to be alive; from the other, execrable sorrow. I was made of their language: shaped by my mother’s tone of voice, silenced by my grandmother’s taciturn manner, I was imprisoned in a rhetorical bind, as everyone is, between life and despair.

The first hard word I ever encountered was ‘impossibility’: the impossibility of sharing the stories told at home with others. I would listen to my grandmother tell various parables rooted in her Alevi faith, only to be forcefully admonished afterward that I ought not to tell others what I’d heard. This was a kind of training in the art of silence. I will not speak at length about how corrosive it has felt to hide that my family are the descendants of the Alevi exiles of Dersim, in particular because my father was an officer and we lived covertly as a religious minority in a military environment, in a hierarchical community that is the state’s singular stronghold for the pure Turkish-Sunni identity. Turkey’s one-nation ideology insists upon the uniform homogeneity of all citizens as the foundation of its Republican revolution; this ideology has so flagrantly failed to stand the test of time that we ought to set aside complaining about it and inaugurate a new time altogether. Because every complaint and denunciation, every language of Otherhood established in opposition to this homogeneity, has the potential to evolve with every passing day into a discourse that promotes further militarism. If nothing else, I refuse any nationalist the right to speak on my behalf. The best way to unshackle the discourses of freedom and justice from the snare of one culture, one minority, one religion or one people, is to let them speak in opposition, simultaneously with everyone and as everyone, without attempting to assume power. This plural language, in my opinion, is so emancipatory that it does not merely compel domestic silence out into the open; it also attaches the language in which that silence belongs to all languages, to all humanity.

I know from my grandmother how pain gives way to silence. And yet, though she was a master of silence, she spoke all the time. That woman constantly talked about her impoverished childhood, about the older sister she lost at a young age, about the many djinns, spirits and beings from the other world whom she saw in her dreams. She would relay her profound wisdom to us, telling us how to pick tobacco leaves, about the healing power of linden, the misery of kneading bread, the way that every drop of water turns to steam and returns to the earth. And she would pair everything in the world up with something else. Just as she paired a star in the sky with a rock on the ground, or mountain with sea, or lake with desert, she paired me with the fig tree in her garden, insisting that the fig tree was my sister. Despite her ceaseless oratory, though, she never once spoke about all the killing she witnessed in Dersim in 1937 and 1938. She had survived one of the most gruesome massacres in the history of the Republic of Turkey, had been torn from her family and exiled from her home, and yet she never once looked back at Dersim, never made mention of it. Even as my grandmother shared all her wisdom about the world, she remained silent about Dersim. Why? What would a person who spoke so much choose to keep silent? Perhaps what kept my grandmother silent was her fear; perhaps it was her solemnity that would not condescend to the language of victimhood; or perhaps, most probably, it was her shame. It was the deep guilt of having survived that hell, a hell that lasted only a few months but in which thousands of people were killed and exiled. It was the shame of being human. It was the insurmountable horror she felt in the face of what mankind does to one another. In another sense, it was her willful forgetting, a way to resist making meaning out of cruelty. Beyond all of this, however, what left her speechless was the sheer futility of speaking in the name of the dead – the people bayonetted, raked by machine guns, abased, poisoned with gas, pushed off cliffs, burned to death in haylofts, the lost community for whom saying ‘They slaughtered us’ could simply never suffice. The fact is, the true witnesses of Dersim were the dead, and they will never be able to speak again. What haunts me most, what my grandmother left me with, is not simply the fact that I was born, but that I descended from her loins, alive. I have a home where I was never born, languages which I never learned, relatives whom I mourn without ever having known them. Even if I wrote for a lifetime, I don’t think I could ever fill that deep void.

In truth, I never really knew my grandmother. I had neither religion like hers to chasten the anguish she left me, nor faith like hers to pair up all the things in the world. What eventually opened up the depths of her spirit to me was Hızır, her god. Without Hızır, the principal deity to the Alevis of Dersim, I would never have been able to fully understand my grandmother’s refuge of silence, her determined lack of anger, which she buoyed with constant prayer and benediction. Hızır was, for her, a symbol of poetic justice; he was an immortal being who could emerge in any place at any time, who appeared and disappeared at a moment’s notice, who shifted from one guise to another, who knew the cause of all things past and future. My grandmother regarded every downtrodden person she encountered as Hızır, feeding them, comforting them and bidding them farewell on their return to the Barzakh, that purgatory between life and death. She treated every beggar like a wounded god, thus pairing up her god with the poor and the hungry; she looked upon strangers as though they were manifestations of the divine. She had nobody else left except her faithful companion, ‘O Hızır,’ as she tended to address him.

In the Al-Kahf surah of the Quran, which narrates the journey the prophet Moses takes with Hızır, Moses is characterized almost as a pupil. Before they embark on their journey, Hızır advises Moses to be patient and not to ask questions in all the situations they will encounter. For Moses, this ends up being a rather difficult journey, because Hızır does a number of unexpected things, damaging the boat of a poor man who aided them, and killing a young boy. In so doing, Hızır serves as a figure who not only tries Moses’ patience, but demolishes his concept of earthly justice as well. According to Islamic theology, Hızır is neither saint nor prophet, neither angel nor dervish, and yet he is all of these at once. Beginning life as the Sumerian god Tammuz, and continuing as a soldier who drank the water of life while on Alexander’s campaign in India, even manifesting in the paintings of Marc Chagall, Hızır has wandered the four corners of the earth under an endless array of guises and names, appearing, finally, before my grandmother, as a poor and wounded man.

My novel Every Fire You Tend stands as a question mark that opens the threshold onto this corrupted world, precisely as it was seen by Hızır and my grandmother. If what we call the novel is an art, then at the same time it is a chamber with two doors that declares a secret undisclosable, that maps safe country for all the exiles of the world, wandering in search of their place. I have reserved a place here for my grandmother, yet I haven’t managed to fit the shame of being human, the shame that she left to me, onto a single page. The more I explored the details of the Dersim Massacre, the heartrending photographs and historical documents that came to light, the more I have come to refuse the notion of inuring the reader to this violence, by making a novel about how this massacre began and how it ended, by portraying these people, already so horribly dehumanized, as if this were their only fate, their only essence, frozen in place and time.

I know from the start that for many this approach might go too far. Given that the first reaction of a society indoctrinated by the lies of official history is to deny and even to blame the victims without mercy, writing a novel about Dersim that spoke to this majority would have been both more sensible and more utilitarian. But when a writer falls in line with the dominant ways of thinking in her country, the first thing she loses is the creative impulse that beckons her to speak authentically, in her own voice. To me, it seems necessary to add to the corpus of world literature, which enumerates the irreparable wounds of genocide and massacre, the solemn consolations an exile offered herself, whether or not they are ever accorded any value.

Adorno once wrote that there can be no poetry after Auschwitz. For some reason, everyone remembers this sentence. Yet fewer ever remember the figure of Paul Celan, the incomparable German poet who survived in a concentration camp, or his ‘Death Fugue,’ which proclaims the insurmountable power of poetry for and by a people facing indiscriminate erasure. Following Celan’s response to Adorno, the philosopher gradually changed his opinion that poetry could never be written again, submitting that the poems of Celan express the most unimaginable horror with profound quietude. In my opinion, the fate of Celan and others like him serves to chronicle the same suffering experienced in Dersim. If the many agonies of the people of Dersim still don’t seem legible to some readers, despite the extensive corpus decrying the suffering inflicted on humanity – and thus on all creatures of the earth and sky – I cannot do anything else except encourage them to imagine themselves as Jews, Armenians, Aboriginal peoples, Native Americans, Bosnians, Khojaly Azerbaijanis, Tutsis or Darfuris.

Finally, I would like to say, I intended to write Every Fire You Tend not just in Turkish, but in the language of all who lament for the dead. And I intended to write it with the language of figs, which I grasped by looking at my sister, at the fig tree whose fruit has, over the course of the history of civilization, seduced and destroyed, poisoned and healed, struck panic in those captivated by its pleasure, and been served like jewels at the tables of kings, pharaohs, and sultans – in order that I might set aside its vitalizing force, its enviable adventure, in writing. What I mean to say is that, over the course of this novel, I am not only my grandmother who survived the massacre: I am also her granddaughter, I am Hızır, and I am a fig, with its countless tiny seeds. Each of us has written the others into being.

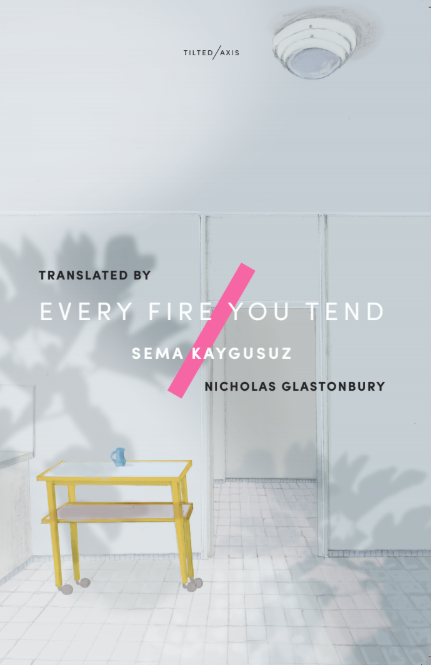

‘A Language of Figs’ is the afterword to Sema Kaygusu’s Every Fire You Tend, available now from Tilted Axis Press.

Image © Kaizer Rangwala